L.A. leaders weigh a new idea to halt rent hikes: Force landlords to sell their buildings

Los Angeles leaders have relied on different strategies for slowing the growth in housing prices — limits on rent hikes in older buildings, new restrictions on Airbnb and incentives for developers who build affordable housing.

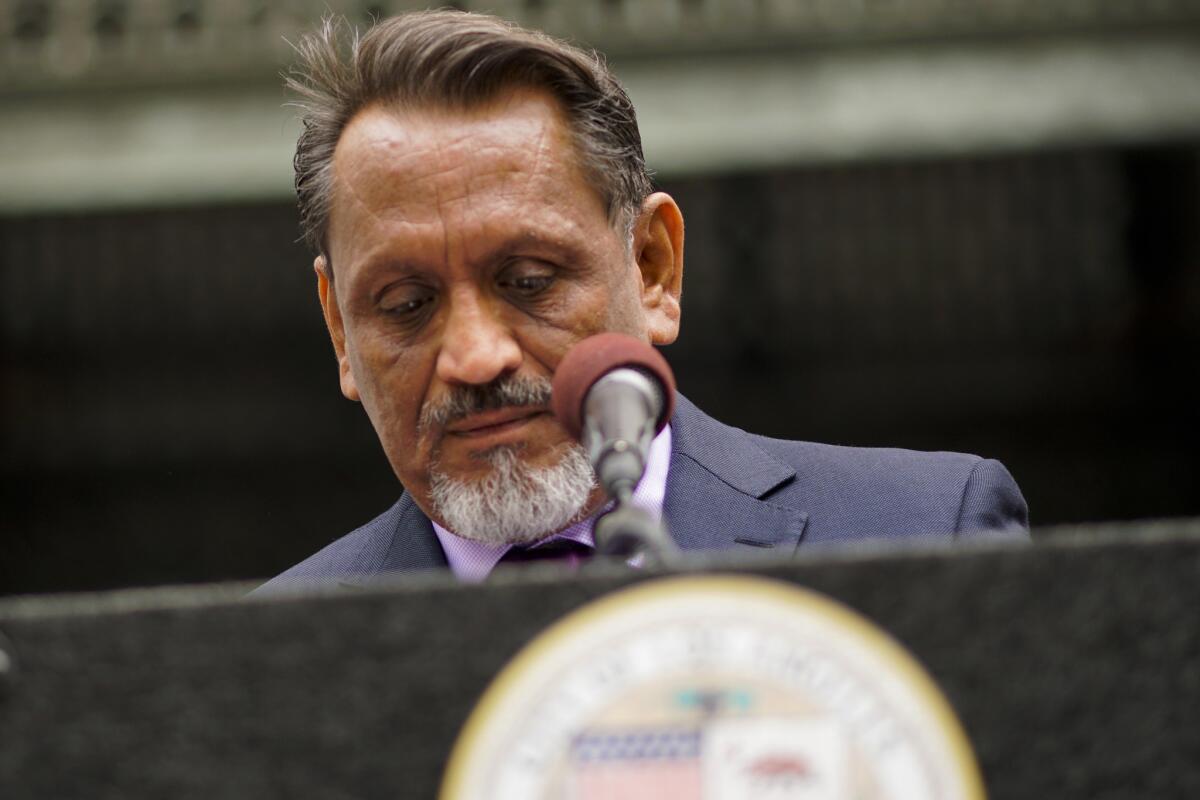

Now, City Councilman Gil Cedillo has another idea for keeping rents low in his district: Force a landlord in Chinatown to sell its building to the city.

On Friday, Cedillo announced plans for having the Board of Public Works — the agency that oversees sidewalk repairs, street repaving and the construction of bridges — use its power of eminent domain to acquire a 124-unit apartment building from landlord Thomas Botz.

Cedillo said the strategy is needed to keep 59 units of affordable housing inside the building, known as Hillside Villa, from switching over to market rate prices. A 30-year agreement to keep rents low between the property owners and city expired in 2018 — and attempts at reaching a new deal have fallen apart.

“We will use all of the resources of the city, both legal and fiscal, to protect these tenants,” he said. “The city is in crisis ... with respect to housing and affordability.”

The Times is launching a new section on latimes.com to bring together our best coverage to date on both homelessness and housing.

Rents in 51 of Hillside Villa’s apartments are slated to go up an average of 50% in September, according to Botz, whose company, 636 NHP LLC, owns the building. In at least one three-bedroom unit, the monthly rent is expected to go from $889 to about $2,500, he said.

Hillside Villa was originally built with the city’s help. In 1986, the city’s Community Redevelopment Agency provided $5.45 million in loans to the developers, who, in turn, agreed to keep rents at affordable prices for 30 years, according to officials in Cedillo’s office.

Botz said he intends to fight any effort by the city to take his property. And he argued that Hillside Villa’s owners never would have agreed to provide the affordable housing three decades ago if they knew the city would renege once the agreement expired.

“If the city goes and expropriates buildings from private developers like us — who have made their 30-year deal and kept their end of the deal — just to have the building taken away at the end, no private developer would build another unit of housing in cooperation with the city of L.A. ever again,” he said.

Still, Cedillo’s proposal has drawn widespread support from tenant rights groups, who have spent nearly a year pressing him to have the city acquire the building. They say eminent domain is the best way to keep households from being forced on the street by skyrocketing rents — and would be less expensive than building affordable housing from the ground up.

A new space for this coverage

Jacob Woocher, an organizer with the Los Angeles Tenants Union, said he thinks Hillside Villa could be worth as much as much as $15 million, roughly $2 million more than the city was looking to spend to ensure that rents on the property stay low for another 10 years.

At a rally last week with Hillside Villa’s tenants, Woocher and other activists said city leaders have had no problem providing taxpayer help to wealthy private interests, such as developers of hotels in downtown L.A.

“I don’t want to hear about price tags. I don’t want to hear about how much it will cost,” said Damien Goodmon, executive director of Crenshaw Subway Coalition, a group focused on fighting displacement in South Los Angeles. “Because the cost of homelessness for these tenants and the many others is far greater.”

Elected officials, both at City Hall and in other local agencies, have long used eminent domain powers to purchase private property for the construction of schools, bridges, train stations, fire stations and other public facilities. However, the city’s housing department has no such legal authority, according to agency spokeswoman Sandra Mendoza.

Instead, Cedillo’s proposal calls for the Bureau of Engineering, which operates within the city’s public works department, to report back in 30 days with recommendations for acquiring the Chinatown property — and possibly other residential buildings that have expiring affordable housing agreements.

Help us inform our reporting about the homelessness crisis in California by submitting your questions.

Elena Stern, spokeswoman for the Bureau of Engineering, said her agency acquires property only for public infrastructure projects in the public right of way. Meanwhile, one lawyer who specializes in eminent domain law said he thinks Cedillo is “posturing” to look good in front of the tenant groups.

Under state law, the city officials would need to demonstrate that they have the legal authority to seize property for the purpose of preserving housing, said Christopher Sutton, an attorney based in Pasadena. Furthermore, Sutton said, the city cannot legally purchase the property unless it pays fair market value — a matter that could take years to resolve in court.

“I think the city has both a legal problem and an economic problem trying to carry this out,” he said.

Cedillo said he offered Botz a deal last year that would have called for the city to cancel the remaining debt on the property if the owners agreed to keep the lower rates for another decade. As part of the deal, the city also would have provided $7.3 million to cover the difference, the councilman’s aides said.

The deal was never signed. Botz said he liked the proposal, but later concluded that he would face another demand from the tenants to extend the agreement within a few years.

Cedillo’s proposal, which was also signed by Councilman Marqueece Harris-Dawson, now heads to the council’s housing committee, which Cedillo chairs.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.