From the Archives: The best houses of all time in Southern California

Architects, preservationists and professors vote on the best houses in Southern California with designs that transcend fashion and time.

(Ken Hively / Los Angeles Times)We asked an expert panel for its top 10 picks in Southern California homes. The results: Schindlers, Neutras, Wrights -- and more than a few surprises.

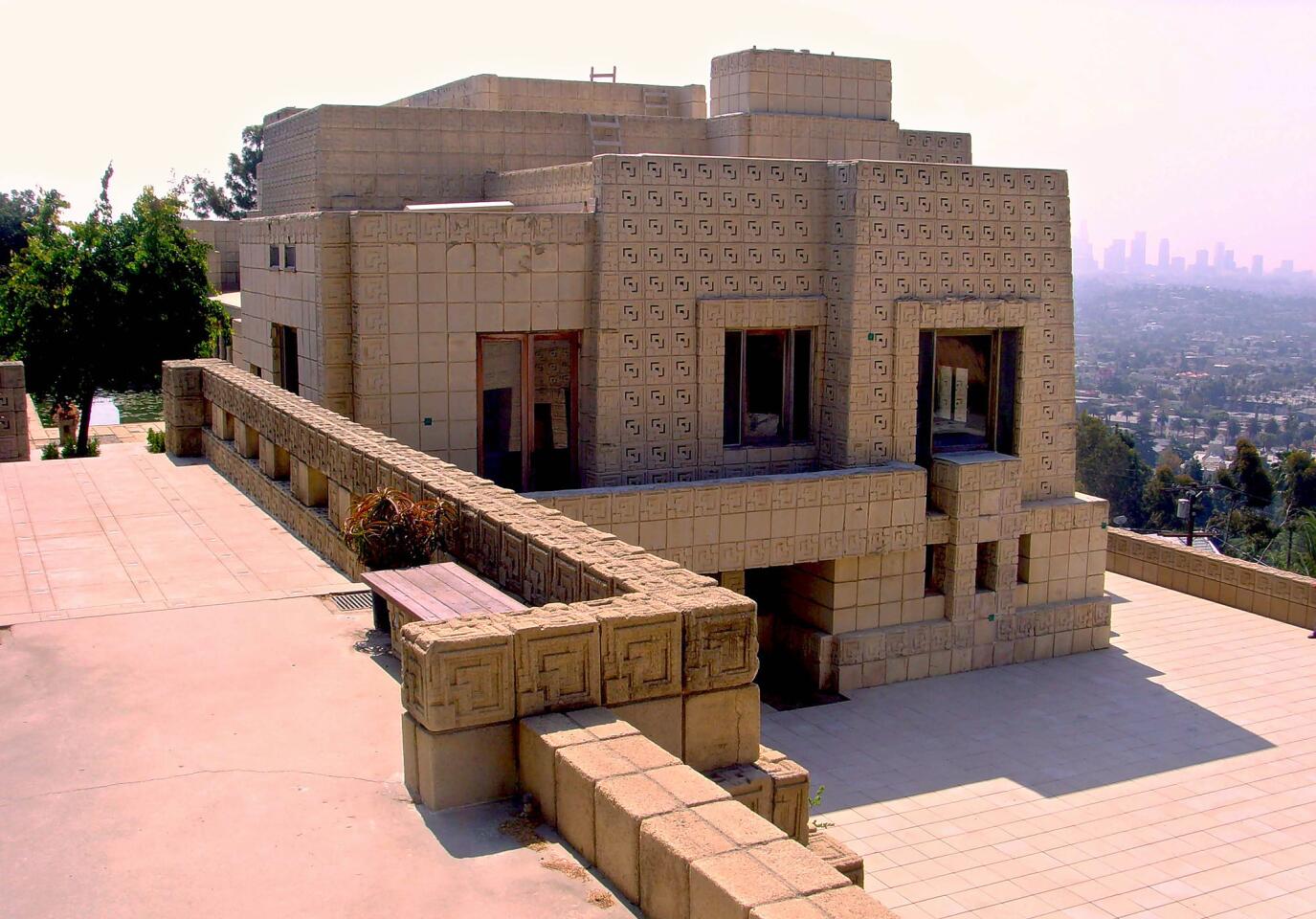

Frank Lloyd Wright, Los Feliz, 1924

The largest and loudest of Wright’s four concrete-block houses in L.A., the Ennis House suggests what the greatest of Modernists would have done with a commission from the Maya Empire 700 years earlier. A heavy, elongated mass constructed of 16-by-16-inch concrete blocks (most textured with an ornate pattern) and sited majestically on a hilltop overlooking Griffith Park, the building appears to be more than a house -- an elegant fortification, perhaps, or a temple.

(Dale Kutzera / For the Times)

It’s a house very much designed for the site, with consciously framed views of Los Angeles built into its plan. A nod to Wright’s genius is that “It doesn’t feel oversized,” said Dishman, whose organization is helping to restore it. In spite of its grandeur -- or because of it -- you might wonder what it would be like to live in the Ennis House, especially if you’ve ever been there at night.

(Carlos Chavez / Los Angeles Times)

The design is timeless enough that Harrison Ford’s character could call it home in the futuristic 1982 film “Blade Runner.”

(Kirk McKoy / Los Angeles Times)Advertisement

What’s compelling about the home, said architectural writer and former Dwell editor Karrie Jacobs, is that it was more than a precursor to prefab. The home, now managed by the Eames Foundation, was filled with furniture the couple designed. “All their stuff is still in it,” Jacobs said. “If you peek in the door, it’s as if they were just sitting there 10 minutes ago.” The primary color exterior panels that suggest a Mondrian painting remain striking. Said Jacobs, “It’s like a big art print sitting there in this big green yard.”

(Ricardo DeAratanha / Los Angeles Times)

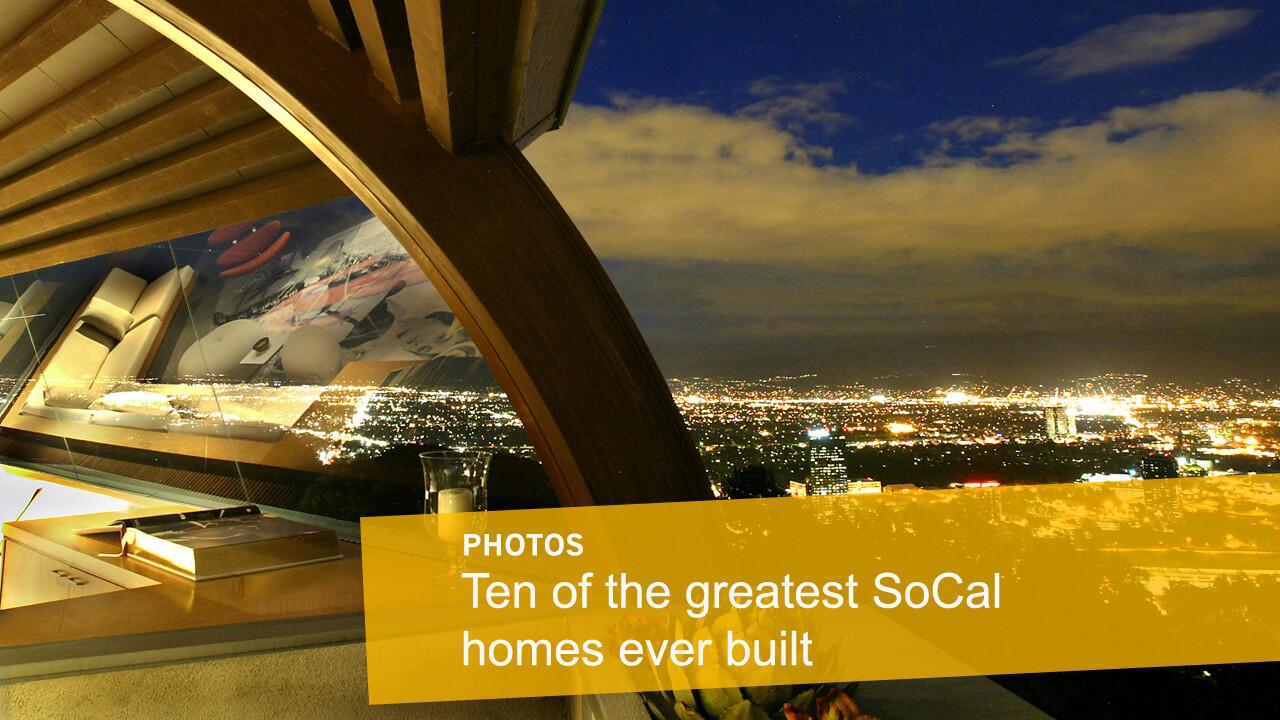

Case Study House No. 22, Pierre Koenig Hollywood Hills, 1960

Whatever the historical and intrinsic values of the other houses on this list, probably none is more famous in the public imagination than Koenig’s 20th century glass-and-steel house. The iconic photograph of it taken by Julius Shulman shows the sleek living room seemingly flying off a cliff in the Hollywood Hills, the romantic nighttime grid of the city flickering far below. Where else could such a photograph have been taken? This was more than just a home. It was a vision of Los Angeles as the future. “It’s a pleasure to be in that house,” said David Travers, formerly editor of Arts & Architecture magazine. “I don’t know what it’s like to live there, but the pleasure principle is heavy in my list.”

(Damon Winter / Los Angeles Times)

Charles and Henry Greene, Pasadena, 1908

One of the so-called “ultimate bungalows” by the influential brothers Greene and perhaps the ultimate bungalow, this wood-shingled shrine and monument to the Arts and Crafts movement in America was built as a California retirement home for a descendant of Proctor & Gamble’s co-founder. By Southern California standards an “old” house, it still belongs to the beginnings of Modernism for its free-flowing floor plan, horizontal lines, broad eaves, exposed beams and Japanese rhythms -- which, along with the dove-tailed, pegged and burnished interior woodcraft make it a masterpiece.

(Ken Lubas / Los Angeles Times)

At 8,200 square feet, the house sorely stretches the term “bungalow,” yet the architectural historian Reyner Banham, after living there for a time, described its distinctive ambience as “close and domestic in spite of its large horizontal dimensions.”

(DeAratanha, Ricardo / Los Angeles Times)Advertisement

John Lautner, Hollywood Hills, 1960

Another L.A. icon, Lautner’s “spacecraft” house -- a seemingly airborne octagonal pod supported by a single concrete column rising from a steep hillside -- is immediately recognizable for its improbable daring and novelty. Many have described it as optimistic and exuberant. An engineering feat that looked like a marriage between the local aerospace industry and the topography, the house, for all its enduring influence, has never been successfully imitated. (Lautner’s 1949 design for the Googie coffee shop at Sunset and Crescent Heights boulevards, by contrast, spawned a Jet Age commercial style still revered by diner enthusiasts.)

(Ken Hively / Los Angeles Times)

Ray Kappe, Pacific Palisades, 1968

Even though the rules of this survey prevented panelists from citing their own projects, Ray Kappe’s house garnered enough votes from other judges to land at No. 8. Though less known to the general public than such contemporaries as

“Ray Kappe’s house may be the greatest house in Southern California,” said Stephen Kanner, past president of the L.A. chapter of the American Institute of Architects. “It’s so creative, not only in the way he’s sited it and the floor plan but the way light moves through the space, the way it hovers up and isn’t pushed into the ground like most houses on slopes.” Kappe used large rectangular concrete pillars to support the wood foundation beams, and the 4,000-square-foot house seems to float. “It constantly relates back to the hillside outside,” panelist Ron Radziner said. “It’s the quintessential tree house.” Kappe, a founder of the Southern California Institute of Architecture, said: “I always appreciated Wright, but I didn’t try to copy him. We were lighter on the landscape than that.”

(Ricardo DeAratanha / Los Angeles Times)

“Spellbinding,” concluded David Travers, the former editor and publisher of Arts & Architecture magazine. The house’s name comes from a favorite flower of Barnsdall’s that is reproduced in stylized form on the roof line, wall columns and planters. Also worth noting is that the house brought Rudolph Schindler to L.A.: He was summoned by Wright to oversee construction while Wright was busy in Japan designing Tokyo’s Imperial Hotel. Barnsdall did not live here long, deciding when it was finished that Hollyhock was more a monument than a home, but she might have approved its use today as a public arts center.

(Annie Wells / Los Angeles Times)