Column: Should we be paying other people to do our grocery shopping?

Recently I was unnerved by a simple question: Should I pay somebody to deliver groceries to my house?

It was day 10 of my family’s self-quarantine and there was no milk in the fridge, a lonely pair of eggs on the bottom shelf, some baby carrots and a single, wilting bouquet of greens in the crisper.

There is only so much takeout one person can eat, and I have a 9-month-old baby who is quite literally cutting her teeth on the softly mashed vegetables we get from the neighborhood grocer.

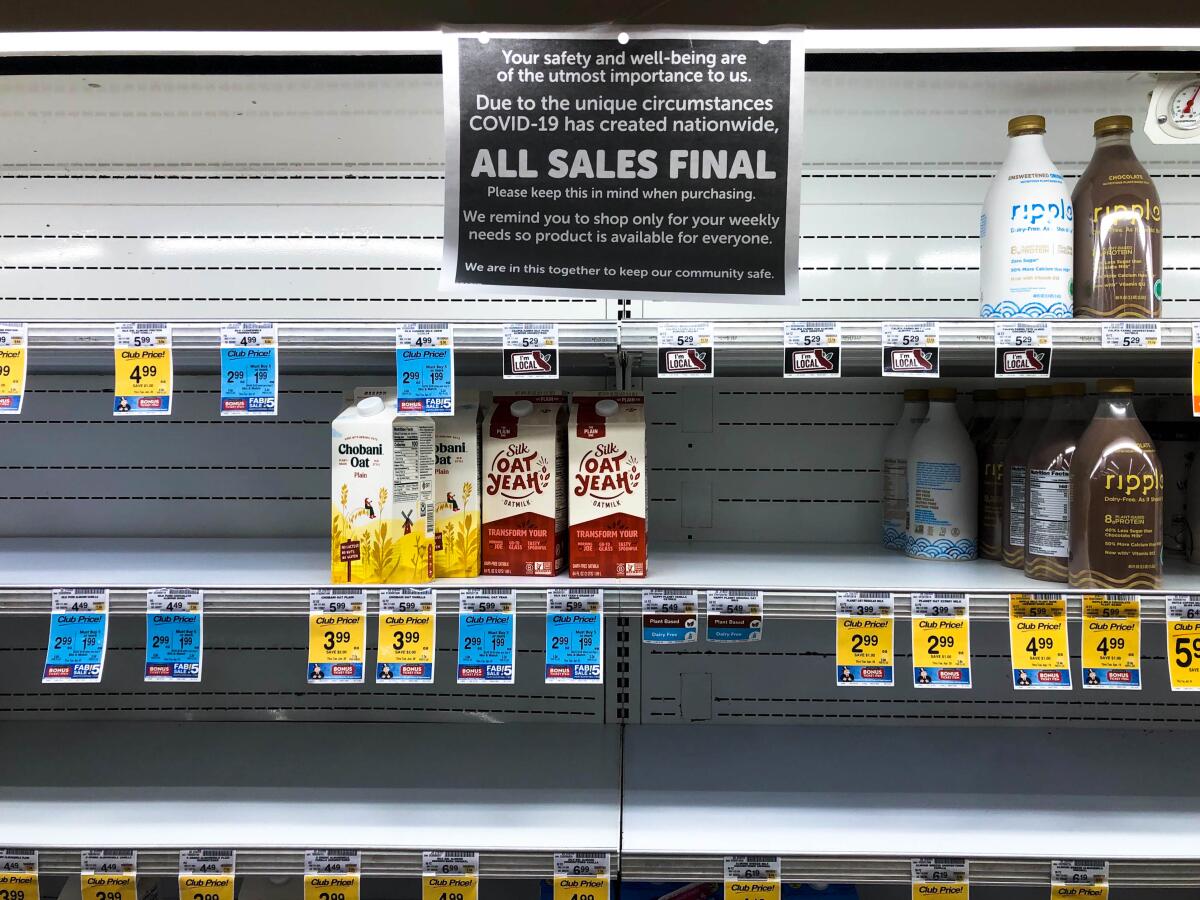

Normally I would make a pit stop at the nearest supermarket, where in better times there are luxuries such as a whole wall of toilet paper, a meat case overflowing with expertly butchered animals, and veritable bullpens full of fresh fruit and vegetables that nobody would think twice about holding, touching or squeezing with ungloved hands.

Before the coronavirus outbreak, grocery stores were mundane, glaringly lighted pillars of everyday life. Now they are one of a small handful of retail businesses still open and, if you have the extreme good fortune to be healthy and safe, they are one of the last bastions of humanity that most of us can’t avoid visiting at least once or twice a month.

I was thinking of all this because my daughter recently came down with her first head cold, a common respiratory infection that doesn’t share many symptoms with COVID-19 but left me sleepless for many nights anyway.

Would I be risking her health by going to buy a bag of avocados or some butternut squash to make her dinner?

Experts say grocery delivery is safer overall than shopping in person, but I don’t have the means to pay for regular deliveries, and neither do most Californians. And outsourcing the task unravels some thorny ethical questions: Should you pay somebody else to risk their health by doing your shopping?

“How is everyone going to the grocery store?” my neighbor Sharon posted last week on Nextdoor, the social network for local communities.

“I’ve got major anxiety about going but I don’t feel right about paying for delivery because I’m still young and healthy and what if the delivery person isn’t? Shouldn’t they be paid more at least?”

Sharon’s right. Contract workers with the grocery delivery app Instacart report making anywhere from $10 to $17 per hour. Many people who find work through the app may not be covered by health insurance or entitled to unemployment benefits.

I spoke with Zach Shervais, a 25-year-old full-service shopper for Instacart in Los Angeles who recently made the jump from driving for Uber to making grocery deliveries for Instacart.

With more people like me wary about venturing into grocery stores, the demand for Instacart shoppers like Shervais is extremely high.

“We all need money in these crazy times,” he said. “I’m young, healthy and I don’t have any family nearby so I’m not worried about getting somebody sick.”

The work allows him the flexibility to juggle the various freelance gigs he’s cobbled together to earn a living, including transcription and online tutoring work.

Shervais made $200 in one day last week, he said, thanks to a particularly generous tipper. But the amount he makes varies from day to day, order to order. Most days don’t look as good.

Here’s a bold idea: For as long as this public health crisis continues to make it risky for vulnerable people — such as the elderly, pregnant women or immunocompromised individuals — to shop, why not pay gig workers a premium for the risk they take to do the shopping for us?

Some Instacart workers recently went on strike to protest inadequate health protections and compensation. Last week the company announced it will begin providing workers with health and safety kits that include hand sanitizer and wipes.

That’s great. Now the San Francisco-based company needs to address a growing call for hazard pay. (I reached out to Instacart for comment but did not receive a response).

Grocery stores are not the same places they were even a month ago. The luxury of not leaving the house to procure food has never been greater. For now, if you can afford to have your groceries delivered, tip generously.

If you’re wondering about what my family is doing, either my husband or I have decided to don a mask and gloves to go grocery shopping for the family about twice a month. So far our family is healthy, and the baby has her avocados. What more can you ask for than that?

More to Read

Eat your way across L.A.

Get our weekly Tasting Notes newsletter for reviews, news and more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.