Koenig’s Case Study House No. 22 as home

Each Christmas they hung their homemade stockings from the crannies of the rock-faced fireplace in the living room. Summers found them diving off the flat roof into the pool for coins their grandfather threw into the deep end, or playing safari in the dense foliage of the hillside below their house, under the glass-enclosed room that cantilevered precipitously above them.

FOR THE RECORD:

Stahl house: A June 27 story on Case Study House No. 22 said 1956 news coverage of architect Pierre Koenig’s work was most likely in a pictorial section of the Los Angeles Herald-Examiner. The coverage was likely in a pictorial section of the Los Angeles Evening Herald Express. —

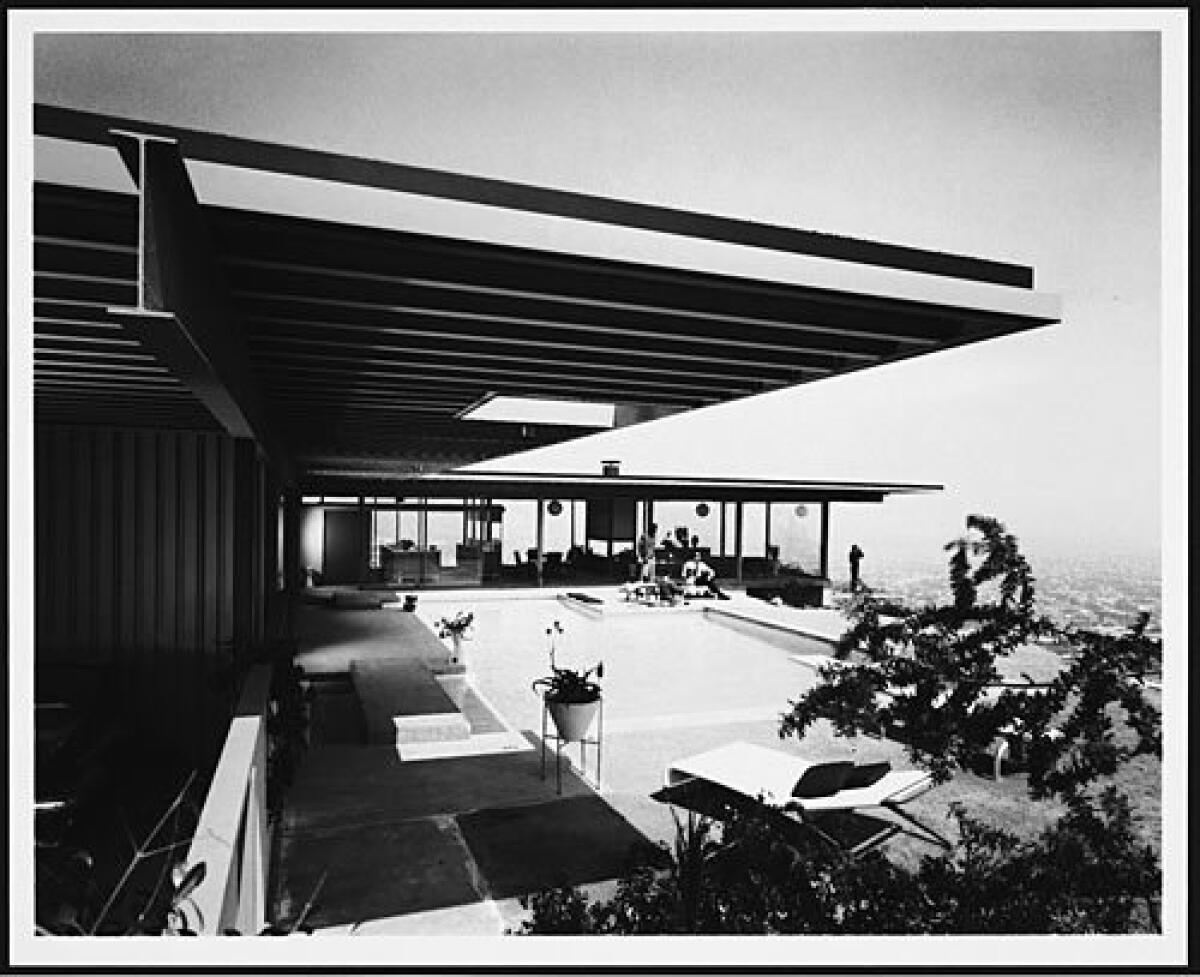

For the Stahl children -- Bruce, Sharon and Mark -- who grew up roller skating on the concrete floors of Case Study House No. 22, the glass-and-steel pavilion perched in the Hollywood Hills has always been more than a landmark. It has been more than the house in Julius Shulman’s famed 1960 photo of two pretty girls suspended in time, floating above the twinkling lights of the city -- arguably the most iconic image of midcentury L.A.

For the children of C.H. “Buck” Stahl and his wife, Carlotta, the house was and always will be “just home.”

As the Stahl house celebrates its 50th birthday and opens for public tours this weekend, perhaps what’s most remarkable is how little people know about the property, despite its fame. The house has appeared in more than 1,200 newspaper and magazine articles, journals and books, not to mention a slew of films, TV shows and commercials.

“When you’re a kid, you don’t think of the house you live in as being anything unusual,” says Mark Stahl, 42, whose family still owns the home. “I first began to think of it as something special in junior high when film companies rented the house to shoot movies. Then later, after bus tours of architects from all over the world began coming, the architectural importance of our home began to sink in.”

Three sides of the home were made of plate glass -- the largest available at the time -- that made for fabulous views. But the windows were not the tempered safety glass used today, and they could shatter into a thousand jagged pieces if anyone were to walk -- or roller skate -- into one accidentally. The radiant-heated concrete floors were sleek, but they were hard and unforgiving for toddlers who fell a lot. Then there was the cantilevered living room that extended 10 feet over the hill -- so dramatic, but just how did one wash all those windows or put up Christmas lights under the eaves?

Eldest son Bruce Stahl, a 2-year-old when the family moved into the house in the summer of 1960, recalls his dad putting up a chain-link fence under the house where the children used to play, simply to keep them from falling down the hillside.

The floors have since been covered with wall-to-wall carpet, the windows have been replaced with shatterproof glass and the cantilevered living room has been given a narrow walkway around its perimeter for window washers.

To many, though, the house will be forever frozen in 1960, the moment when those two pretty girls sat for Shulman’s photo. Nevermind that they were not members of the Stahl family -- just two students that the photographer used as models. And all that glorious midcentury furniture in the living room? Every piece was brought in by casual furniture maker Van Keppel-Green to decorate the house for its premiere in the pages of Arts & Architecture magazine as part of the Case Study House Program.

Begun in 1945, the program aimed to introduce the middle class to the beauty of modernism: simplicity of form, natural light, a seamless connection between inside and out. Owners agreed to open up their homes as part of the program, but after the public tours wrapped at the Stahl house, every stick of furniture was hauled away, daughter Sharon Stahl Gronwald says.

“My mother always said she wished they would have left it,” says Gronwald, 49. “They were given the option to buy the furniture, but my parents didn’t have the money at the time.”

Indeed, over the years the house has been appointed with contemporary furnishings with nary a midcentury chair in sight.

Perhaps the most surprising fact is that the original inspiration for the design may not have come from architect Pierre Koenig but rather his client, Buck Stahl.

::

Before the children were born, the house was the dream of Buck Stahl, a former professional football player, his children say, then a purchasing agent for Hughes Aircraft. In 1954, he and Carlotta were renting a house in the Hollywood Hills when he spotted grading equipment on an empty lot nearby.

“My dad told me he went down to see what was happening, and the owner just happened to be there,” Mark Stahl says. “Two hours later, he shook hands on a deal.”

Sale price: $13,500.

“At the time he got a lot of teasing from the family,” says son Bruce, 50. “In those days you could have gotten a three-bedroom home in the flats for the amount my dad paid just for the lot. My grandfather told my dad, ‘You’ll never get your money out.’ The whole family thought my parents were crazy.”

Buck Stahl spent two years collecting broken-up concrete from construction sites and hauling it to the lot in his Cadillac convertible. He dedicated most weekends to building the retaining walls for what would be the front and back of the house. In the Life magazine article “Way Up Way of Living on California’s Cliffs,” dated Feb. 23, 1962, Stahl is shown dangling “1,000 feet above Los Angeles” from a rope tied around his waist, planting ivy around his concrete terracing to secure the hillside.

Architect Koenig was hired in 1957. Construction didn’t begin until September 1959 and finished in May 1960. The two-bedroom, 2,200-square-foot house cost $34,000 to build; the pool, $3,651 more. Buck passed away four years ago, and today Carlotta and the three children have no intention of selling, though there’s a list of wannabe owners -- recognizable figures in the film and fashion world, the family says, although they decline to cite names. The highest offer so far: $15 million.

::

That might be the end of the story if it were not for a previously unpublished photo from the family album. Taken in July 1956, 16 months before Koenig received the commission, the image shows a shirtless Stahl posing with his nephew Bobby Duemler next to a large-scale model of a glass-and-steel house. It bears more than a passing resemblance to the iconic design attributed to Koenig.

Is it possible that Stahl deserves some of the credit for the house?

The children say the initial concept of the home was their father’s, though it’s possible he may have been influenced by Koenig’s other work when building the model. Buck Stahl had seen photos of the architect’s elegant steel and glass homes before the two men ever met. In a 2001 Los Angeles Magazine article, Carlotta remembered seeing a “pictorial section of the Sunday paper,” most likely the Pictorial Living Section of the Los Angeles Herald Examiner in 1956, which featured layouts of Koenig’s work. The family archives include an article from Roberts News by Toni Edgerton in 1957 that talked about Koenig’s steel homes.

“My dad always wanted to build his own house with a completely unobstructed view of the mountains to the sea,” Bruce Stahl says. “I think he’s not given enough credit for the initial design of the home. It’s not exactly the same, but it’s pretty darn close.”

Brother Mark agrees, saying that their father played a larger role in the design than history has recorded.

“It was a collaboration,” he says. “Pierre bought into my dad’s vision but made alterations to make it buildable. In the end, he gave my dad what he wanted.”

The CA Boom contemporary design show this weekend will include shuttle tours of the home, still considered by many the archetypal 20th century Southern California house. Show impresario Charles Trotter says the “aha” moment for attendees will be when they learn the extent to which Buck Stahl worked with Pierre Koenig “in this masterpiece of modern architecture.”

However, the architect’s widow, Gloria Koenig, dismisses the idea that the house should be credited to Stahl.

“Pierre used to say that every client thinks they designed their house,” she says, “and this is a perfect example of that.”

Architect and writer Joseph Giovannini, former architecture critic of the Herald Examiner, recalls Stahl telling him that he had “given Pierre the idea for the house.”

“I dismissed it as typical owner hubris at the time,” Giovannini says. However, upon seeing the photograph of the model, he changed his mind.

“The gesture of the house cantilevering over the side of the hill into the distant view is clearly here in this model,” he says. “But it is Pierre’s skill that elevated the idea into a masterpiece. This is one of the rare cases it seems that there is a shared authorship.”

::

One thing seems certain: Koenig was the right architect at the right time. Others had turned down the project. The jagged-edged hillside lot was problematic, and Buck Stahl insisted on a 270-degree uninterrupted view. He also had Champagne tastes and a beer budget, the children say.

According to family lore, Koenig honed Buck Stahl’s ideas into a masterpiece. In Stahl’s model, the two-bedroom wing along the pool was curved, with the carport between the bedrooms. Koenig straightened out the curve, relocated the carport to the end and changed the butterfly-type roof to a flat tar-and-gravel roof.

“The design indeed shares certain similarities with what was later built, but Pierre Koenig would never have introduced curving forms into his work, and I’m struck by the pronounced arc of the house’s wings in Stahl’s model,” says Elizabeth Smith, a former curator at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles and organizer of the seminal 1989 exhibit “Blueprints for Modern Living: History and Legacy of the Case Study Houses.”

“From this I can infer that Koenig adhered to the basic attributes of Stahl’s concept but refined the design into something much more rigorous, geometric and ‘pure’ in its form and materials -- in essence adapting it to his own vocabulary.”

One of Koenig’s innovations was to use the largest possible sheets of glass available at the time for residential construction, reducing the presence of framing elements so that the house seems to float, Smith says.

Adds Giovannini: “Koenig suspended disbelief along with gravity when he designed the daring, transparent structure, capturing in a single building what modern life in a modern house could be.”

In the end, Buck, Carlotta and their children got their home -- a modern dream house that lives on for them, as well as for other Angelenos for whom Shulman’s photo represents the halcyon days of mid-20th century.

“My dad loved the house,” Gronwald says. “He never wanted to leave.”

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.