Most Read in This Section

-

Nov. 5, 2024

-

-

-

By Barbara Thornburg

As architect Steven Ehrlich tells the story, it was seredipity that he came upon an Inglewood design by Schindler, whose iconic Kings Road House in West Hollywood is often considered the big bang of California Midcentury Modernism. Family friends Kali Nikitas and Richard Shelton had invited Ehrlich and his wife over to dinner.

“As soon as I walked through the door,” Ehrlich said, “I asked, ‘Is this a Schindler?’” It was. And so was the house next door, which shared a frontyard with Nikitas and Shelton’s place. As fate would have it, the Schindler next door was the subject of a probate sale the next day. Ehrlich put in the winning bid ($265,000) and set out to renovate the house for his daughter’s young family. (Katie Falkenberg / For the Los Angeles Times)

On a quiet street in Inglewood, twin 1940 homes by midcentury legend Rudolph M. Schindler have been renovated by owners intent on making the most of the two-bedroom, one-bath floor plans. The goal: Respect the historic architecture while updating the spaces for modern living.

Ehrlich sits on the front steps with Onna Ehrlich-Bell, who owns the house now, and sister Vanessa Ehrlich, who lives across the street. For two years, the architect spent much of his time “channeling Schindler,” he says. Ugly fiberglass overhangs on the front and back of the house were removed, and Ehrlich rebuilt the entire roof based on a photograph that Julius Shulman had taken of a third Schindler house on the street. (Katie Falkenberg / For the Los Angeles Times)

Ehrlich-Bell and her husband, Joel Bell, in the remodeled kitchen. A new peninsula counter made of Caesarstone quartz doubles as the couple’s dining table. New cabinets wear solid-core plastic laminate veneers with back-cut faces for door pulls, a classic Schindler detail. Contemporary appliances include a Wolf range, a Miele dishwasher and a SubZero refrigerator. “We didn’t feel like we needed to find a fridge or an oven from the ‘40s,” Ehrlich says. “If Schindler were alive, he would be using the materials of today.” (Katie Falkenberg / For the Los Angeles Times)

Let’s eat! Son James, 2, in the modernized kitchen. (Katie Falkenberg / For the Los Angeles Times)

In a utility room adjacent to the kitchen, a large hot water heater was replaced with a compact unit. But left in place: a vintage sink and a classic fold-down ironing board. (Katie Falkenberg / For the Los Angeles Times)

The free-flowing, indoor-outdoor feeling of the house was preserved, with an Ikea sofa floating in the center of the living room. The house still had its original doors and windows, so Ehrlich refinished the wood frames, stripped the hardware and inserted tempered glass for safety. The house has air conditioning, but it’s rarely used. The concrete-and-brick fireplace had to be stripped of paint. The wood floor was so badly damaged by cat urine, though, that it had to be removed. New oak was milled and installed in the narrow-plank fashion favored by Schindler. (Katie Falkenberg / For the Los Angeles Times)

Bell in the living room. When he, his wife and her father pulled up the previous owner’s shag carpet, an outline on the floor suggested a built-in desk had been part of the original plan. Schindler homes often featured built-in furniture, so Ehrlich built his own, taking inspiration from the built-in desk in the Schindler house next door. (Katie Falkenberg / For the Los Angeles Times)

The master bedroom, with a strong connection to the landscape outside. (Katie Falkenberg / For The Times)

In the bathroom are the same back-cut drawer pulls as seen in the kitchen. The original medicine cabinet as well as a vintage wall heater were replated. The vintage diamond-shaped tub was in terrible condition, so a modern shower with 1-inch-square tiles and glass door were installed in its place. Fluorescent lights were replaced with more energy-efficient LEDs. “Keeping it all white in the small bathroom and kitchen made both rooms appear bigger, brighter and happier,” Ehrlich says. (Katie Falkenberg / For the Los Angeles Times)

James’ room, full of light. (Katie Falkenberg / For The Times)

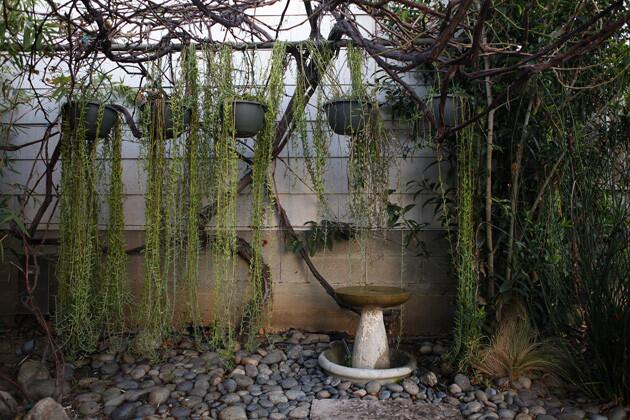

Inspired by Schindler’s sleeping porch at the landmark Kings Road House in West Hollywood, Ehrlich designed a steel trellis for the Inglewood backyard. Although Schindler used wood, Ehrlich opted for galvanized steel. “We knew the grape arbor was going to grow over it, and we didn’t want it to rot,” Ehrlich says. “We also wanted it strong enough to hang swings and a hammock.” (Katie Falkenberg / For The Times)

The result: an outdoor living room for mom and dad to complement the play space for little James. (Katie Falkenberg / For The Times)

A view back toward the house. (Katie Falkenberg / For the Los Angeles Times)

A picture of peace. (Katie Falkenberg / For The Times)

When Ehrlich-Bell first saw the property in its run-down state, she didn’t even go inside. “I peeked in the window and saw a filthy shag carpet and peeling wallpaper,” she said. Her husband, however, did take a look and was instantly convinced it could be made into a good family home. (Katie Falkenberg / For The Times)

Landscape designer Stefan Hammerschmidt was called in to renovate the garden as well. (Katie Falkenberg / For The Times)

Hammerschmidt created a xeriscape in front punctuated by agaves, aloes, ornamental grasses, decomposed granite and a bench made from stacked concrete recycled from the backyard. It’s a communal space for the side-by-side Schindler homes. Owners of both houses regard one another as extended family. “We often begin the day by having a cup of coffee outside around the fire pit,” Bell says, adding that they also take turns caring for each other’s dearest loved ones: Bell’s toddler, James, and Shelton and Nikitas’ toy poodle, Ravi. (Katie Falkenberg / For The Times)

James runs toward his neighbor’s house. (Katie Falkenberg / For The Times)

Kali Nikitas seen through the kitchen window of her Schindler house. She and husband Richard Shelton had all but given up their house search in 2007 when the academic administrators at Otis College of Art and Design in Westchester came upon a listing for this house on Craigslist. [For the Record, Dec. 23: An earlier version of this caption said the college was in Westminster.] (Katie Falkenberg / For The Times)

Built in 1940, Nikitas and Shelton’s house was in decent shape with a strong foundation but has required the systematic removal of inappropriate alterations. Pictured here: the dining and living areas, with natural light spilling in from both sides. Schindler was an early pioneer of seamless indoor-outdoor spaces. “What I love about the house is how completely open and completely closed it is at the same time.” (Katie Falkenberg / For the Los Angeles Times)

Generic kitchen tiles that had clad the fireplace mantel were removed. Additional tiles to the left of the fireplace also were taken out, revealing traces of a built-in. The Schindler house down the street still had its original built-in kindling box, so Nikitas and Shelton used that as a model to build a similar one. (Katie Falkenberg / For The Times)

Before they had reached a deal, the previous owner had asked Nikitas and Shelton what they planned to do with the house. The couple answered in unison: Restore it. “That must have been the right answer,” Shelton says. (Katie Falkenberg / For the Los Angeles Times)

The asymmetric mantel: Schindler-esque simplicity. (Katie Falkenberg / For The Times)

The reverse view, looking back toward the dining area, decorated with a well-edited mix of contemporary and vintage furnishings. Framed Russian propaganda posters from the 1960s hang on the wall. (Katie Falkenberg / For The Times)

The kitchen has its own connection to the outside. The room is on the couple’s to-do list, and at some point the 1980s cabinets will be replaced with something more in keeping with a Schindler home. (Katie Falkenberg / For The Times)

An ornate Spanish railing on a patio area atop the garage was removed. (Katie Falkenberg / For The Times)

The master bedroom closet with built-in drawers, pictured here, and another closet in the guest room were the only places where wood had not been painted by a previous owner; elsewhere in the house, Nikitas and Shelton had to strip paint off marine-grade plywood to take the house back to Schindler’s intent. The glass block separating the bedroom from the living room allows more light to reach the interior of the house. (Katie Falkenberg / For The Times)

Light and shadow in the master bedroom. The house, Nikitas says, “reminds us how living simply is a good way to live. There’s a simplicity and a feeling living here I’ve never experienced before.” (Katie Falkenberg / For The Times)

“We are in the house of our dreams,” Nikitas says. “Not a day goes by that we don’t thank our lucky stars. We call it the Big Miracle.” (Katie Falkenberg / For The Times)

This house makes its indoor-outdoor connections in ways that are different from the Schindler next door. “When doors and windows are thrown open, it almost feels like we’re outside,” Nikitas says. Here, Shelton looks out the expansive glass toward ... (Katie Falkenberg / For The Times)

... a patio area that sits slightly below. (Katie Falkenberg / For The Times)

Nikitas and Shelton in their outdoor room. (Katie Falkenberg / For The Times)

A wider view. (Katie Falkenberg / For the Los Angeles Times)

From left: Rich Shelton (holding Ravi), Onna Ehrlich-Bell (holding James), Joel Bell, Kali Nikitas, architect Steven Ehrlich and daughter Vanessa Ehrlich, who lives across the street. “If I need some mint, I go to Onna’s vegetable garden,” Shelton says. “And if I’m going to the store, I call her to see if she wants something. … We are really living this wonder back-and-forth communal life.”

More profiles: California homes in pictures”

West Coast scene: L.A. at Home blog (Katie Falkenberg / For The Times)

Nov. 5, 2024