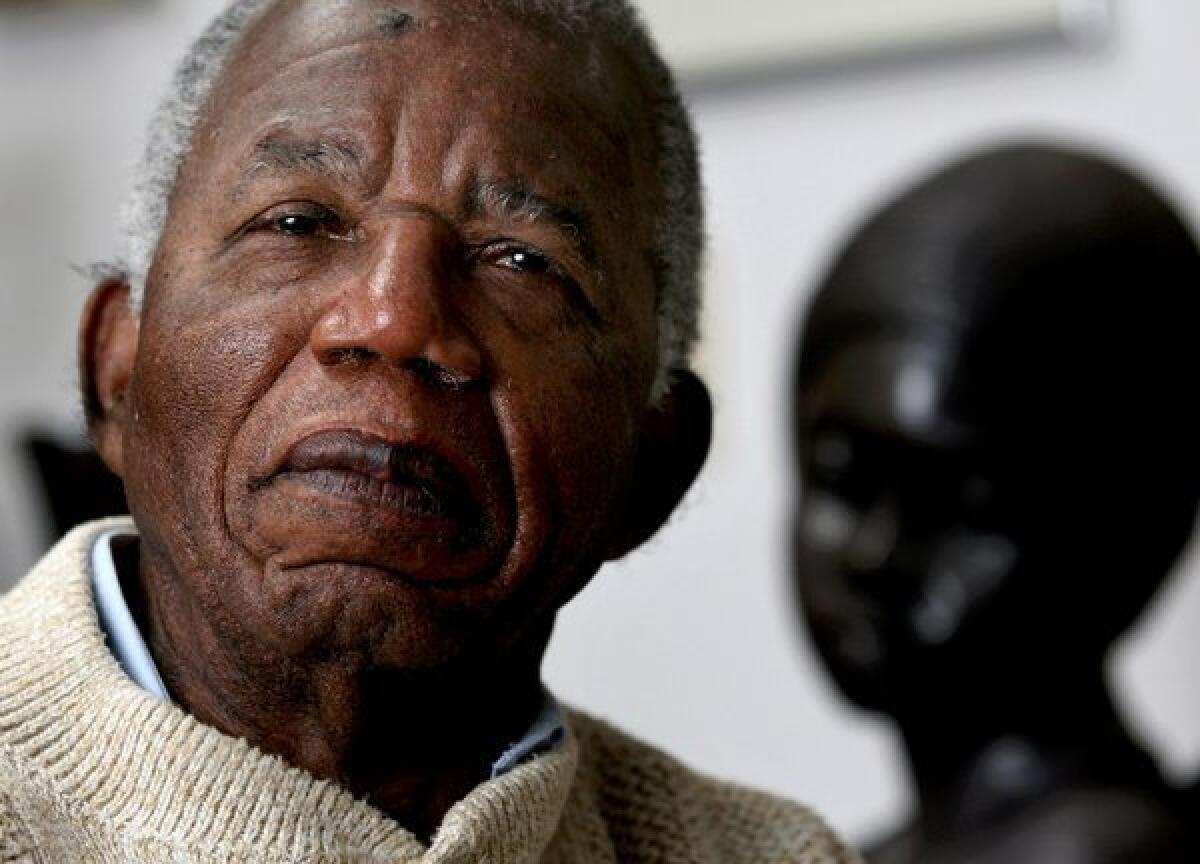

Remembering Chinua Achebe, a writer who connected us to the world

When I think about Chinua Achebe, who died Thursday in Boston at age 82, I remember an event, five years ago, at Manhattan’s Town Hall. The occasion was a commemoration, sponsored by PEN American Center, of the 50th anniversary of Achebe’s first novel, “Things Fall Apart,” which opened the territory of African literature for many readers around the world.

I listened as, one after the next, novelists Colum McCann, Edwidge Danticat and Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie took the stage to pay homage to Achebe. Toni Morrison read an essay about the author she’d written in the 1960s; Chris Abani — like Achebe, a Nigerian writer — spoke in Ibo before switching to what he called “the more primitive language” of English.

At the end of the evening, Achebe appeared onstage in his wheelchair, wearing a black beret. (He was partially paralyzed in a 1990 car accident.) He spoke slowly, noting his surprise that a tribute to a novel about Africa could fill a theater in New York.

PHOTOS: Chinua Achebe’s literary legacy

“Did I take the decision?” he wondered about the choice to undertake the novel. “Or did the decision take me? The same with the writing: That book wrote me. … I worked and worked and worked definitely under its spell.”

This was the most stirring moment in an evening of stirring moments, reminding us that literature is an art of connection, and that the first connection it must provoke is between the writer and the work.

“Things Fall Apart” is, of course, a groundbreaking novel, one that literally helped to create a literature. Fifty-five years after its publication, it continues to be widely read and taught, highlighting, as it does, issues of identity and colonialization, the push and pull of modernity and tradition.

And yet, to read it only in terms of its iconic status is to miss the point of Achebe’s narrative, which traces with grace and nuance the clash of traditional and western cultures through the figure of a man, Okonkwo, caught between the old ways and the new.

Okonkwo’s struggle to preserve both his identity and that of his village is tragic, for he is doomed by the very strengths that in another time might have served him: his sense of his position, of his responsibility and, ultimately, his sense of self. This is the key to the novel, that it is both representative and abidingly personal, that it is about a single character, a person, caught at a turning point of history.

Such a sensibility, with its tension between past and present, between the individual and the collective, defined Achebe as a writer, and as a human being.

Achebe went on to write four more novels (most notably “No Longer at Ease” and “Arrow of God,” which along with “Things Fall Apart,” formed what is known as the “African Trilogy”), as well as essays and children’s books. His final book, the memoir “There Was a Country: A Personal History of Biafra,” came out late last year.

Deeply, profoundly African, he made his home in the United States for many years as a professor at Bard College and later at Brown; perhaps most controversially, he wrote his books in English, the language of the colonizers who, in many ways, he sought to write against.

For his critics, the decision to work in English was problematic, but Achebe argued that it was impossible to strip away the language of the oppressors even if the oppression itself were systematically destroyed. English was a tool, “a language with which to talk to one another” — and even more, a structure to be infiltrated, in which an African writer (or any writer) “can try and contain what he wants to say within the limits of conventional English or he can try to push back those limits to accommodate his ideas.”

More to the point, as Philip Gourevitch observed online at the New Yorker on Friday, “Achebe — who has gone to his grave without ever receiving the Nobel Prize he deserved as much as any novelist of his era — has said that to be called simply a writer, rather than an African writer, is ‘a statement of defeat.’”

In that sense, “Things Fall Apart” is not just the starting point of African literature, but of modern African literature: contemporary, hybrid, global in its implications, influenced by everything, and richer for it in its evocation of the world.

For this reason, perhaps, the most affecting tributes to Achebe are the most personal, the testimony of younger writers whose lives he helped dream into being. In a 2009 TED talk, Adichie credited him with helping her to realize “that people like me, girls with skin the color of chocolate, whose kinky hair could not form ponytails, could also exist in literature,” a point she also made at Town Hall.

There are many legacies to Achebe’s remarkable career — as a novelist, as an activist, as a teacher, as a critic whose 1975 reassessment of Joseph Conrad’s “Heart of Darkness” marked a turning point in the discussion of that work.

But most important, he offered permission to half a century of writers, African or otherwise, declaring forcefully and without apology that literature can encompass any and all stories, that everyone should have a stake. It’s no stretch to suggest that without Achebe we would be a literary culture with fewer voices, less engagement, less of a sense of how wide a world writers can (and should) engage.

ALSO:

Reactions as the world mourns Chinua Achebe

Chinua Achebe obituary: Nigerian author Chinua Achebe, 82, dies

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.