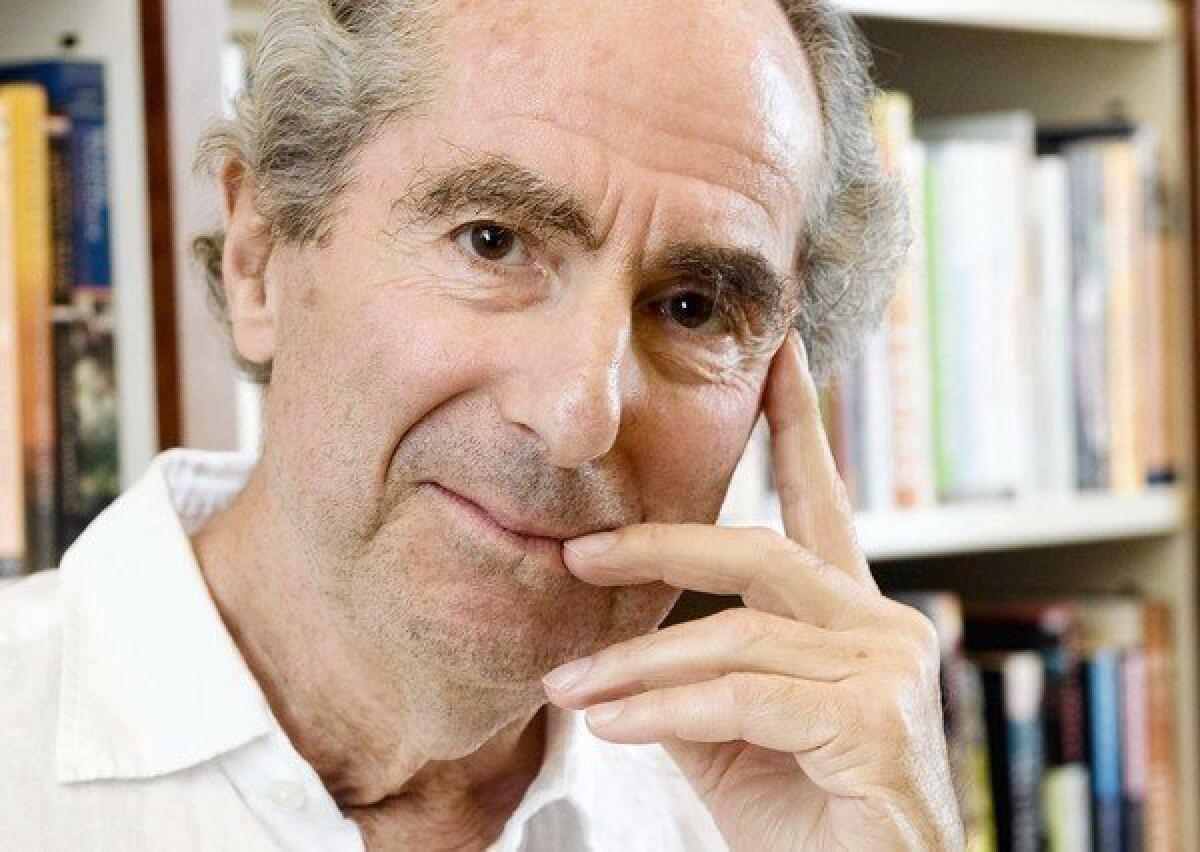

Philip Roth in Pasadena (sort of) talks career and retirement

On Monday afternoon, at the Langham Huntington in Pasadena, Philip Roth stole the show.

Roth was not there in person -- but his half-hour appearance via satellite (part of the Television Critics Assn. Press Tour) in support of the upcoming PBS “American Masters” documentary “Philip Roth: Unmasked” offered a vivid reminder of his flinty brilliance, undiminished since he publicly retired from writing a few months ago.

Roth is an unlikely television spokesman -- even for a show about himself. Asked what he liked to watch, he demurred, mentioning the news (“half an hour a night”) and, in the summer, a few innings of baseball, before adding that, on the whole, he preferred to read.

“You only have so much time,” Roth observed, which was also the reason he gave for having agreed to be interviewed for this documentary, his first. “Time is running out, you know?” he said. “And if I didn’t do it now, when would I do it?”

In part, Roth -- who turns 80 on March 19 -- was talking about mortality, which has been one of his great subjects all along. “I couldn’t stop myself,” he writes in his 2000 novel “The Human Stain,” describing the revelation that strikes his character Nathan Zuckerman while watching a rehearsal at Tanglewood. “The stupendous decimation that is death sweeping us all away. Orchestra, audience, conductor, technicians, swallows, wrens -- think of the numbers for Tanglewood alone between now and the year 4000. Then multiply that times everything. The ceaseless perishing. What an idea! What maniac conceived it?”

Yet equally, he was referring to retirement. “It’s great so far,” he joked, noting that he had worked seven days a week for half a century. “I wake up in the morning, get a big glass of orange juice and read for an hour and a half. I’ve never done that in my life.”

Pressed about the possibility of reconsidering, he laughed: “I’m doing fine without writing. Someone should have told me about this earlier.”

For Roth, the issue is that writing is a struggle -- a struggle in which he no longer wants to engage.

“I always found writing a difficult process,” he said, although over the years, the nature of the process changed. Asked to compare the experience of writing his first book, “Goodbye, Columbus” (1959), with that of his last, the 2010 novel “Nemesis,” he elaborated: “I think the elation is the same; when you finish, you feel triumphant. The agony is different.”

“Goodbye, Columbus,” he went on, was a necessary statement, a way of carving out a place for himself in the world. The same was also true of later touchstone efforts: “Portnoy’s Complaint” (1969), in which he found his comic voice -- manic, ribald, uncensored; “The Ghost Writer” (1979), in which he reinvented himself yet again through the introspective figure of Zuckerman; “The Counterlife” (1986), which is, I think, one of the three or four greatest 20th century American novels, a ruthless deconstruction of both character and form.

“You’re a different writer in each book,” Roth said. “I’m particularly partial to a book called ‘Sabbath’s Theater,’ which a lot of people hated” -- because its protagonist, Mickey Sabbath, is unconventional, antisocial even, a kind of walking expression of the id. When he finished that novel, Roth turned in an entirely new direction, writing “American Pastoral,” about a man as conventional as they come.

It’s no surprise that Roth was in a retrospective mode, given the occasion: to discuss a documentary about his life. And yet, he remains pointed, iconoclastic, honest, willing to say exactly what he thinks.

“I ran with some very fast horses,” he said, talking about postwar American fiction, and contemporaries such as William Styron, E.L. Doctorow, John Updike and Joyce Carol Oates. “Now, the Nobel Prize committee doesn’t agree with me. They think we’re provincial. But I suspect they’re a little bit provincial.”

There is, perhaps, a subtext to this statement; the Nobel is the one major literary prize Roth hasn’t won. But more to the point, it is a summing up, a reflection on the engagement, the commitment, required by literature. “You’re working for your own freedom,” Roth said of writing, “to lose your inhibitions, to delve deeply into your experience and find the prose to bring it to life.”

Hard work, yes, but then again, he went on, “All work is hard. Everybody’s job is hard. You build a book out of sentences. And the sentences are built up out of details. So you’re working brick by brick. And the bricks are heavy.”

ALSO:

David Malouf’s pursuit of happiness

National Book Critics Circle announces finalists for awards

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.