David Bowie’s stylish shape-shifting sizzle caught our eye while camouflaging the man behind the art

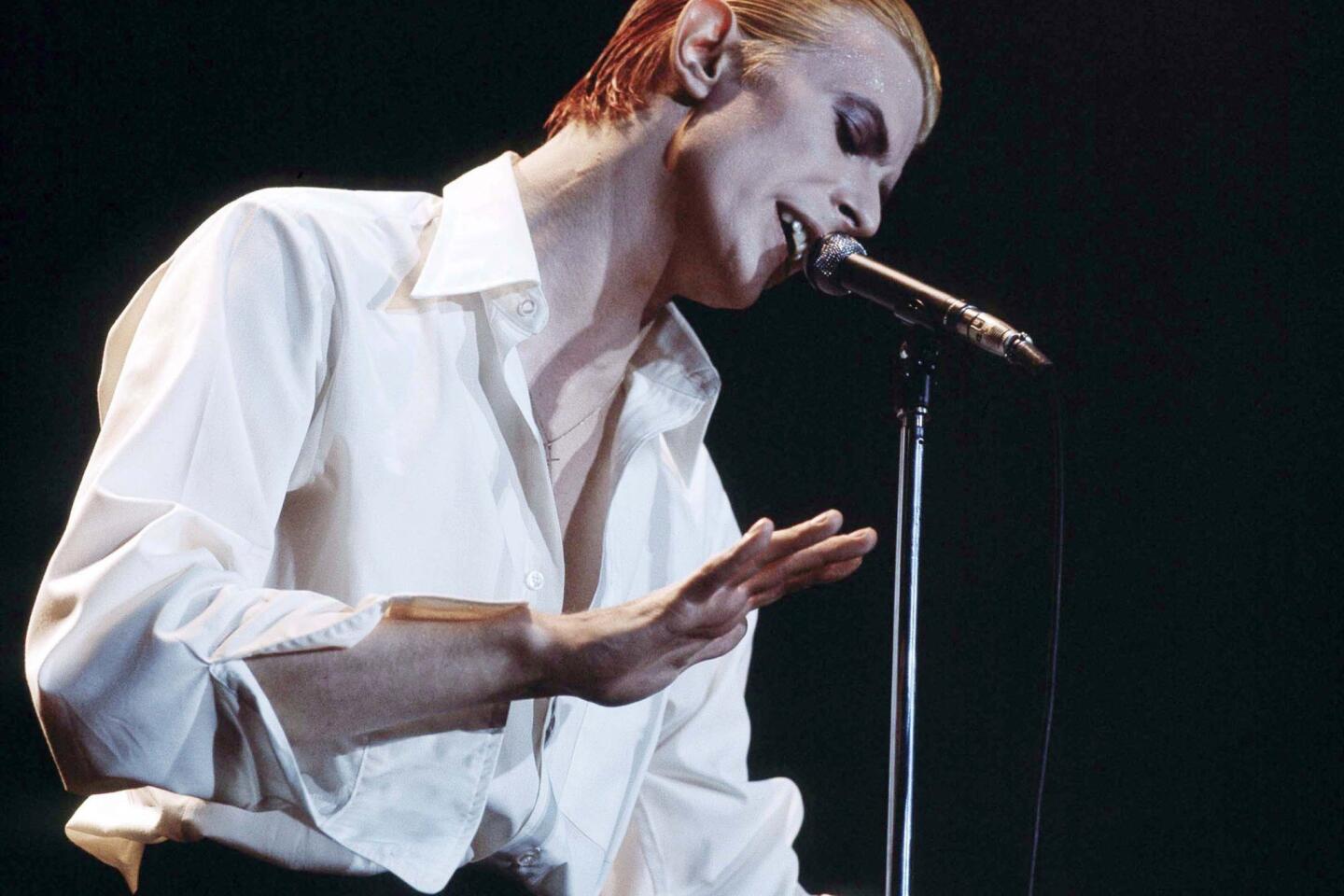

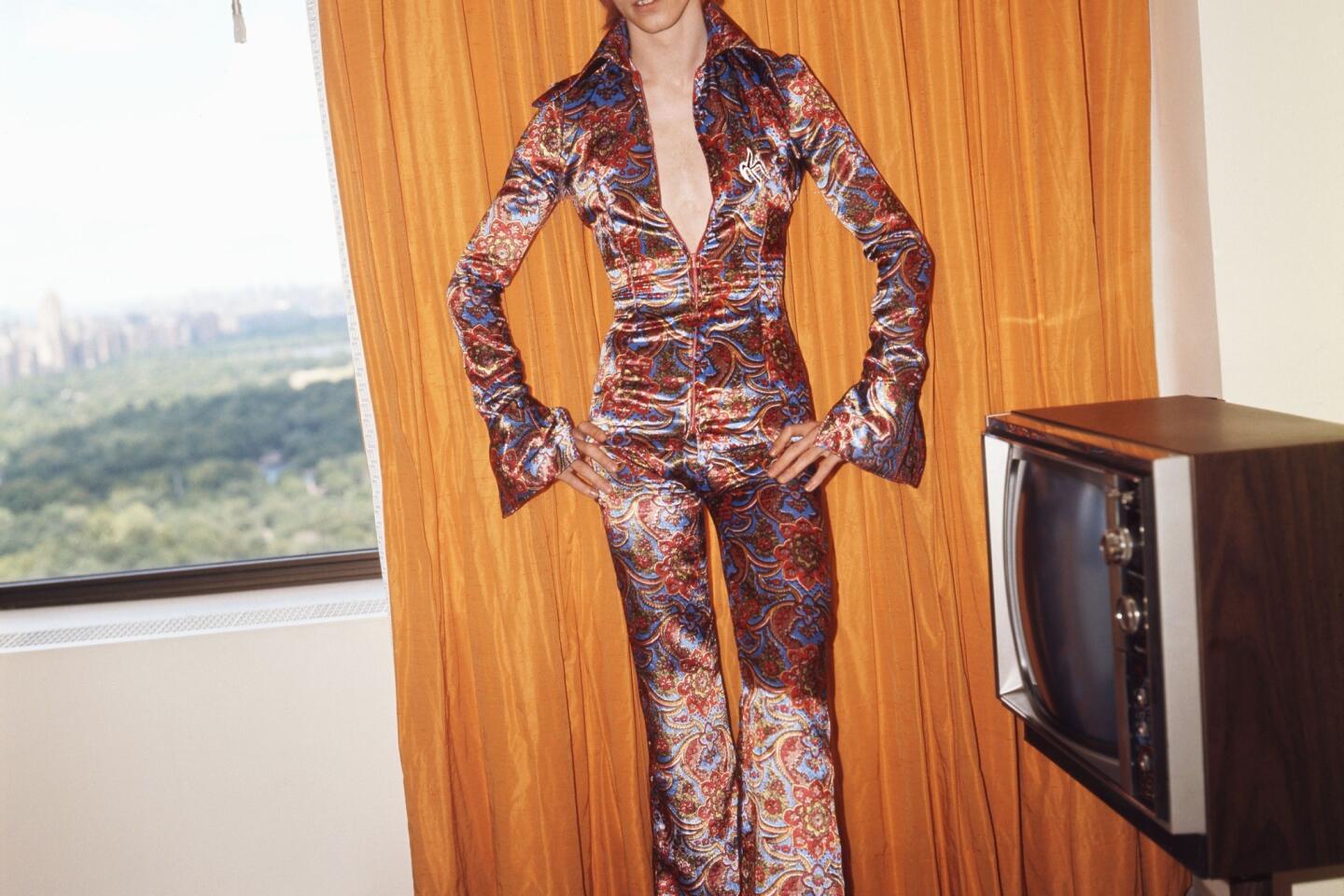

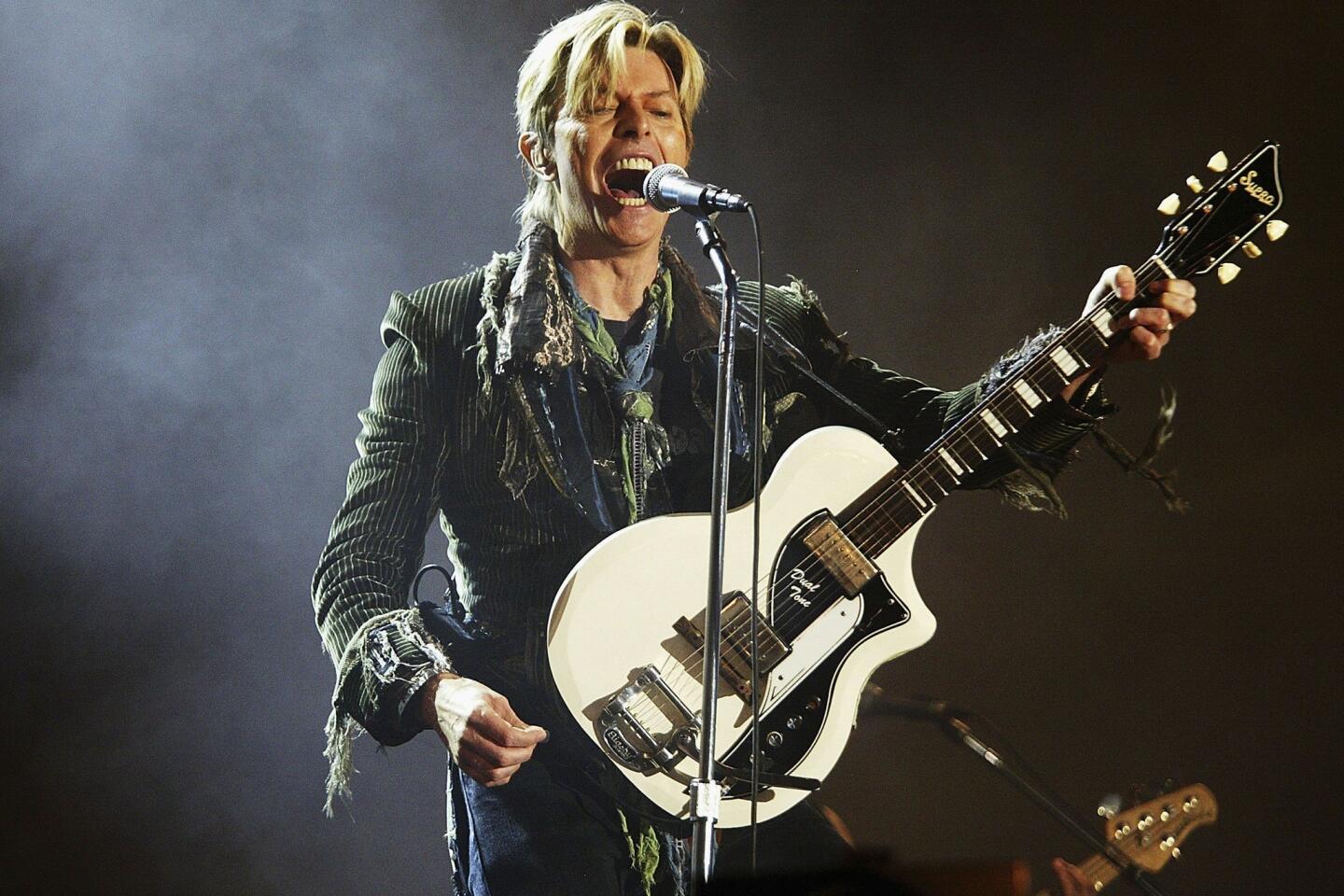

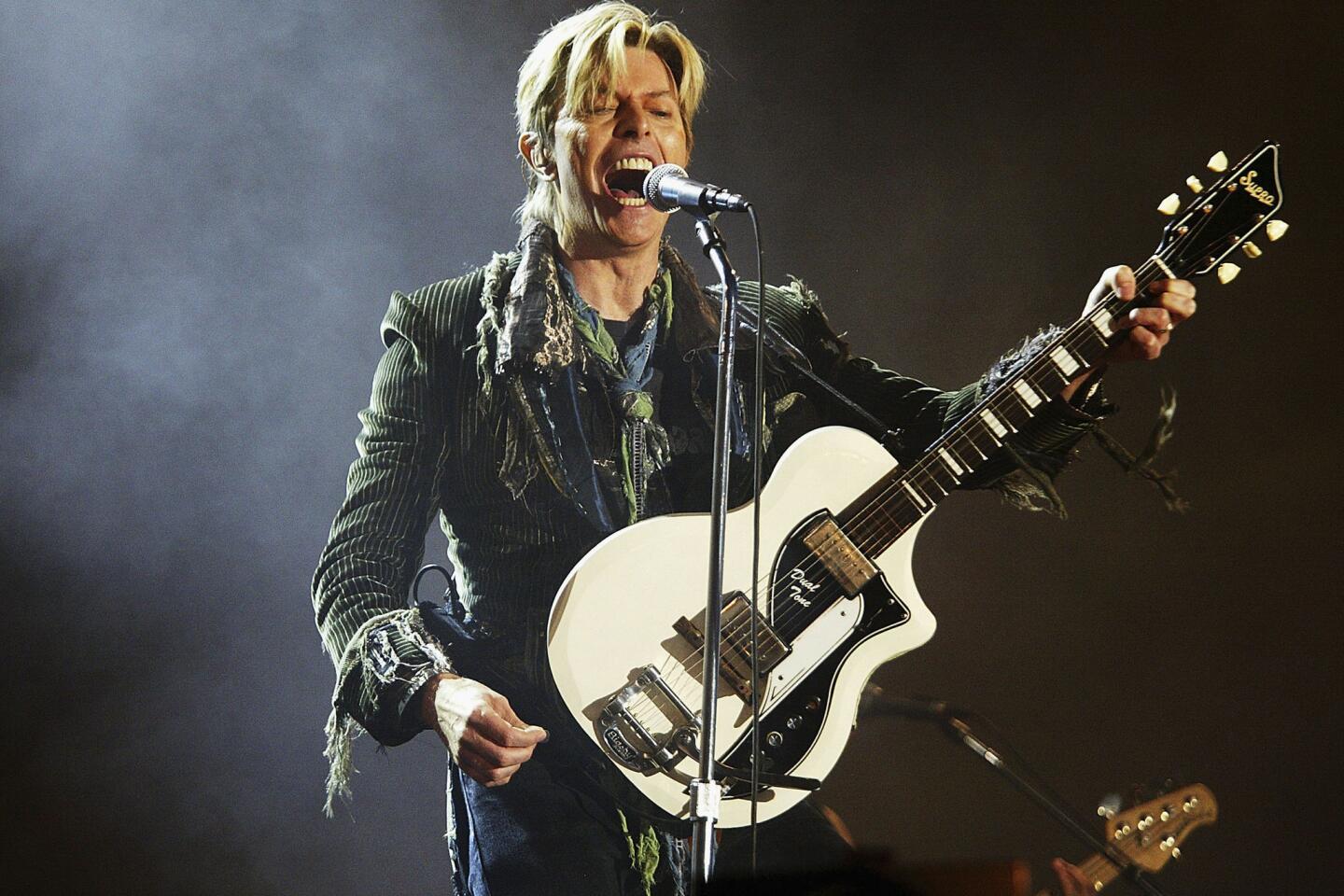

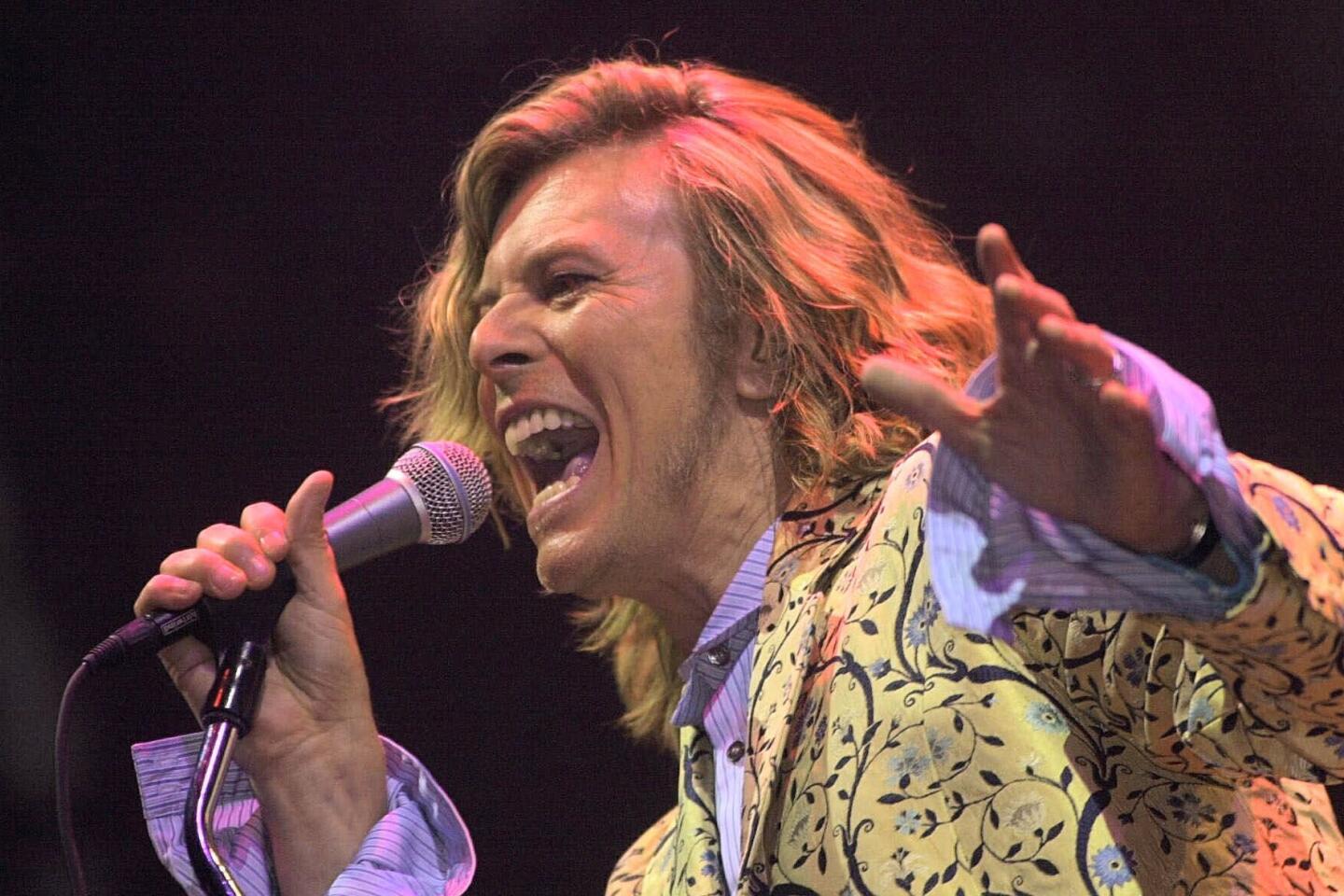

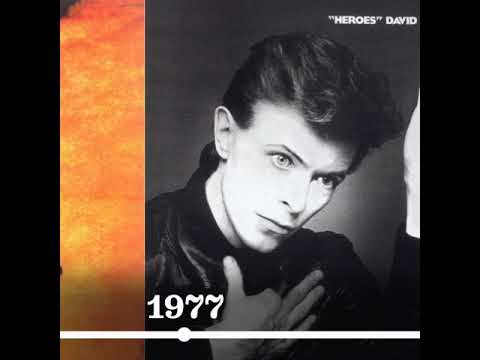

David Bowie’s half-century career will be defined, as it well should be, by his music output. But it can’t be altogether untangled from his signature look — or rather looks, each one telegraphing the arrival of a totally different Bowie: Ziggy Stardust, Aladdin Sane (with the lighting bolt across his face), the Thin White Duke, the minimalist black-and-white version from his Berlin period.

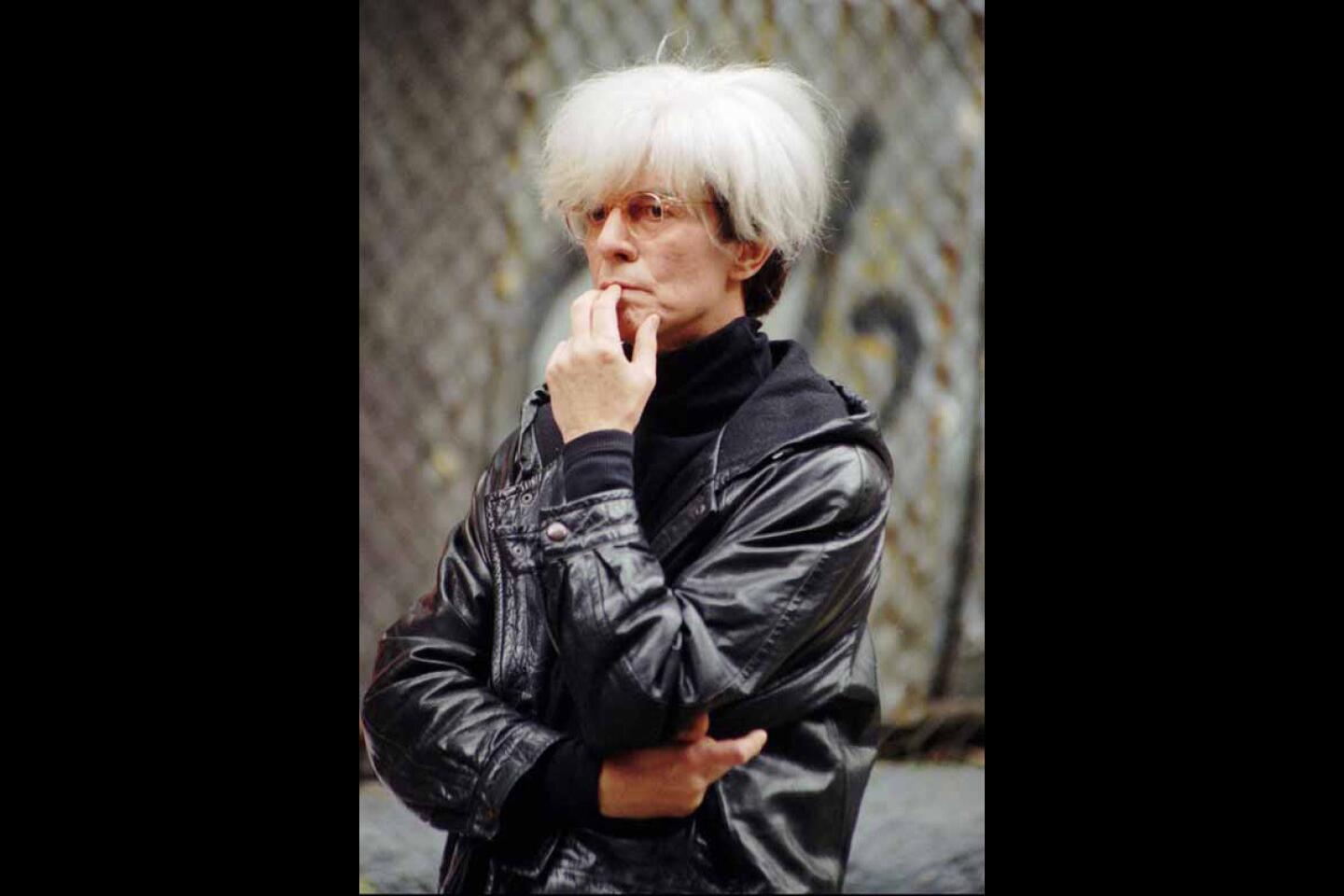

From the vantage point of a cynical 21st century, it’s easy to look at the over-the-top costumes, the face paint, the magenta teased-high mullet and the enthusiastic bending of gender as a premeditated, well-executed exercise in branding: shape-shifting sizzle to sell music. Especially when this aspect of Bowie is what influenced fashion runways, Hollywood red carpets and Berlin nightclubs for decades, provided a template for the chameleon-like careers of Madonna, Lady Gaga, Janelle Monae and Adam Lambert — and made Bowie the subject of a 2013 Victoria & Albert Museum exhibition in London that’s touring the globe.

See more of Entertainment’s top stories on Facebook >>

Keanan Duffty, a New York fashion designer who worked with Bowie on a 2007 clothing line for Target, thinks this view — that Bowie style was merely premeditated packaging — is off the mark.

“I don’t think it was as much a calculation as it was the guy just got bored and wanted to create the next new thing,” Duffty said. “He’s like a true artist in that way.”

The various permutations of self that Bowie brought to bear weren’t calculated stagecraft but rather full-on performance art, an outward expression of the musician’s inner self.

Despite Bowie’s considerable influence on fashion, Duffty said, Bowie didn’t seem to care for it all that much.

“When we first met, he was wearing a pair of suede shoes, ill-fitting jeans and a Tommy Hilfiger T-shirt and said something to the effect of: ‘I’m not particularly interested in fashion,’ and I was actually quite enlightened by that,” Duffty said. “I think he took the bits that worked for something he was creating and used them as part of the palette. ... I think he saw [the clothes] as this great vehicle for what he was doing, so he jumped into it — but he wasn’t afraid to jump out of [one kind of garb] into another ... and not really worry about whether he was in or out of fashion.”

Victoria Broackes, co-curator of “David Bowie Is,” which debuted at the V&A Museum three years ago (and is at the Netherlands’ Groninger Museum), was unavailable for comment Monday but echoed Duffty’s sentiments in a 2013 Los Angeles Times interview.

“He says himself he’s not that interested in fashion,” Broackes said, “yet the exhibition is going to have 60 costumes including pieces from [Alexander] McQueen and Kansai Yamamoto. It’s a performance exhibition but it could just as easily have been a fashion exhibition.”

She said Bowie’s shape-shifting persona imbued him with a “shamanistic” quality.

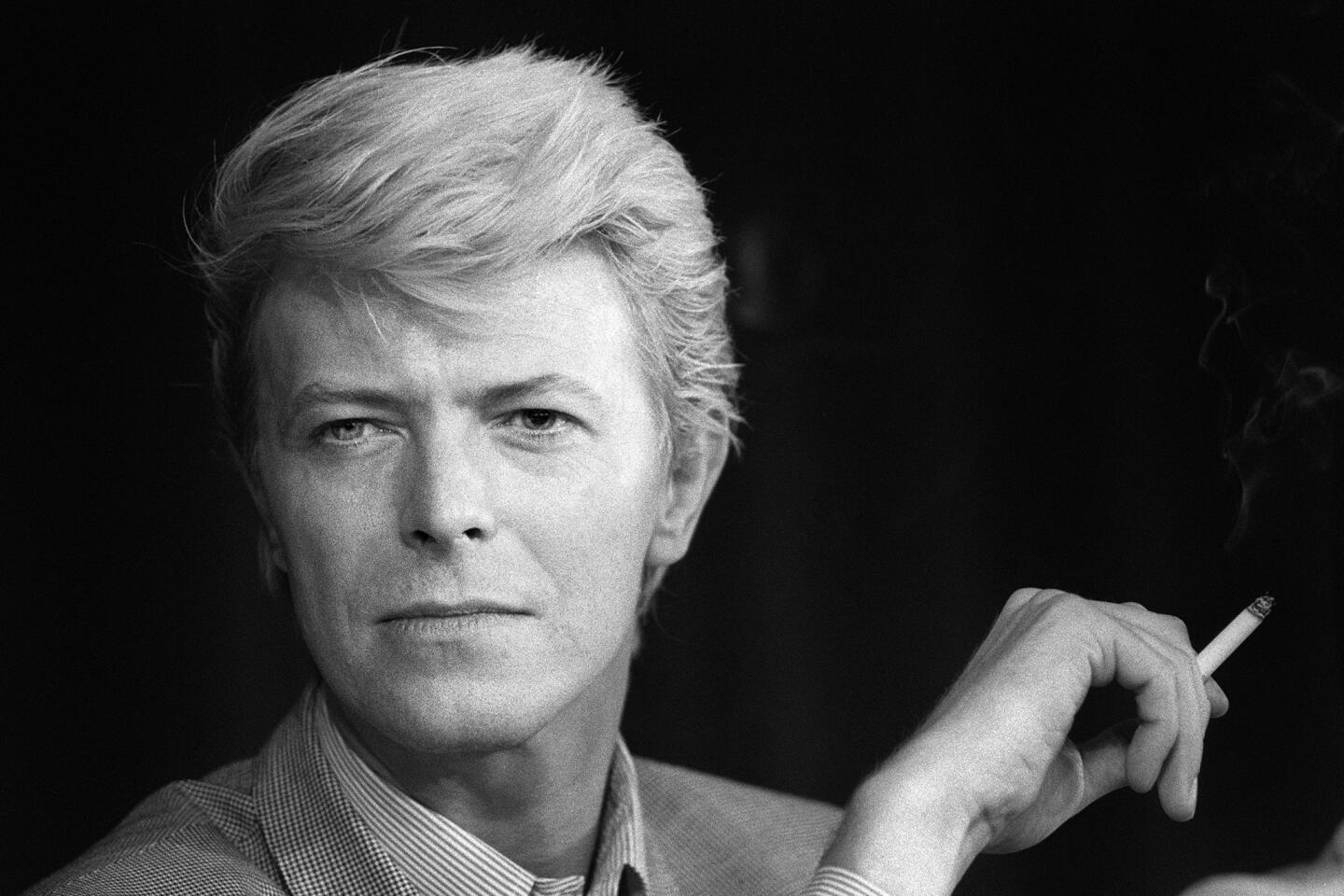

“There’s all this mythology. But do we know him? No,” she said. “We know these things about him — I think I know a lot about him — but do I know him? No.”

A timeline of David Bowie’s studio releases

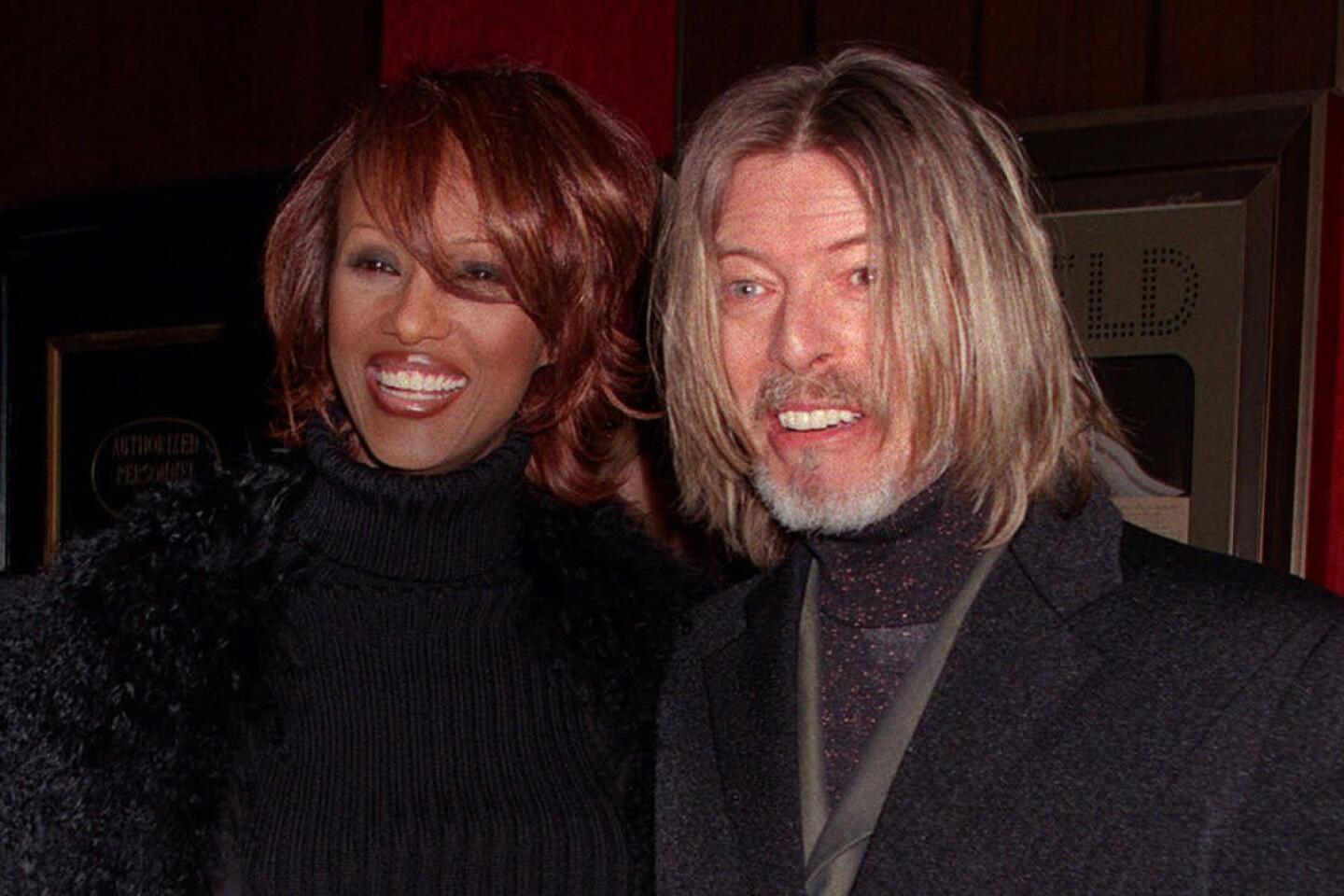

Whether the looks were the outer expression of the inner artist or merely stylistic smoke-screen — or perhaps some combination of the two — the result was that Bowie, born David Jones, controlled the world’s perception of who he was.

And that’s really what the clothes and the costumes were really about: defining and redefining the artist, keeping the pop culture tractor beam from locking in on one iteration that might force him to be someone or to do something that he didn’t want. Duffty alludes to that aspect of Bowie’s personality in describing the launch of the Bowie by Keanan Duffty apparel line.

“Target wanted me to ask him to perform two songs to support the launch,” he recalled. “When I did, he looked at me and said: ‘I’m not … Posh Spice!’ That’s the way he was. He didn’t play by anybody else’s rules, he didn’t do anything he didn’t want to do, and he did what he did with 100% participation, and when he was done, he dropped it.”

Whatever the genesis, and whether he was a fashionista at heart or not, the cycle of looks turned out to be beneficial to the Bowie brand.

“People got this message that they could be whatever they wanted to be and that Bowie was a sort of conduit to that freedom — that’s what he represented,” Broackes said.

The fearless experimentation meant a lot of different looks that Bowie could latch on to. That in turn made him a staple on fashion mood boards around the world. In the Internet era of his career, Bowie matched fashion fearlessness with the element of surprise. His 2013 album, “A New Day,” the first new album in a decade, seemed to come out of nowhere and take everyone off guard. His most recent, “Blackstar,” recorded during the 18 months he was battling cancer, includes “Lazarus,” a tune that serves as a final bow, on his terms.

At the end of the video for “Lazarus,” posted online just three days before the musician’s death, Bowie appears in a black outfit with wide diagonal stripes of white, a visual callback to his bold ‘70s-era looks.

The video ends with Bowie backing slowly into a freestanding wooden wardrobe and pulling the doors shut after him.

It should come as no surprise that David Bowie, in full control, exits through the clothes closet, the way he was introduced to so many of us so many decades ago.

MORE:

Full coverage: David Bowie’s life and career

Remembering David Bowie through his 100 favorite books

Mikael Wood review: David Bowie looks far beyond pop on jazz-inspired ‘Blackstar’

From the Robert Hilburn archives: David Bowie spends the ‘80s convincing us he’s just a normal guy