Storms pummeling Southern California have dramatically transformed Death Valley National Park, doubling the size of a vast temporary lake that is even visible to orbiting spacecraft.

Although water sports are a definite rarity for the hottest place on Earth, park ranger Abby Wines recently launched a small inflatable kayak on the waters that now cover the salt flats of Badwater Basin.

It was “calm, really, really peaceful” and “very still,” she said of her voyage late Friday afternoon. She returned the next day with her boyfriend for another go.

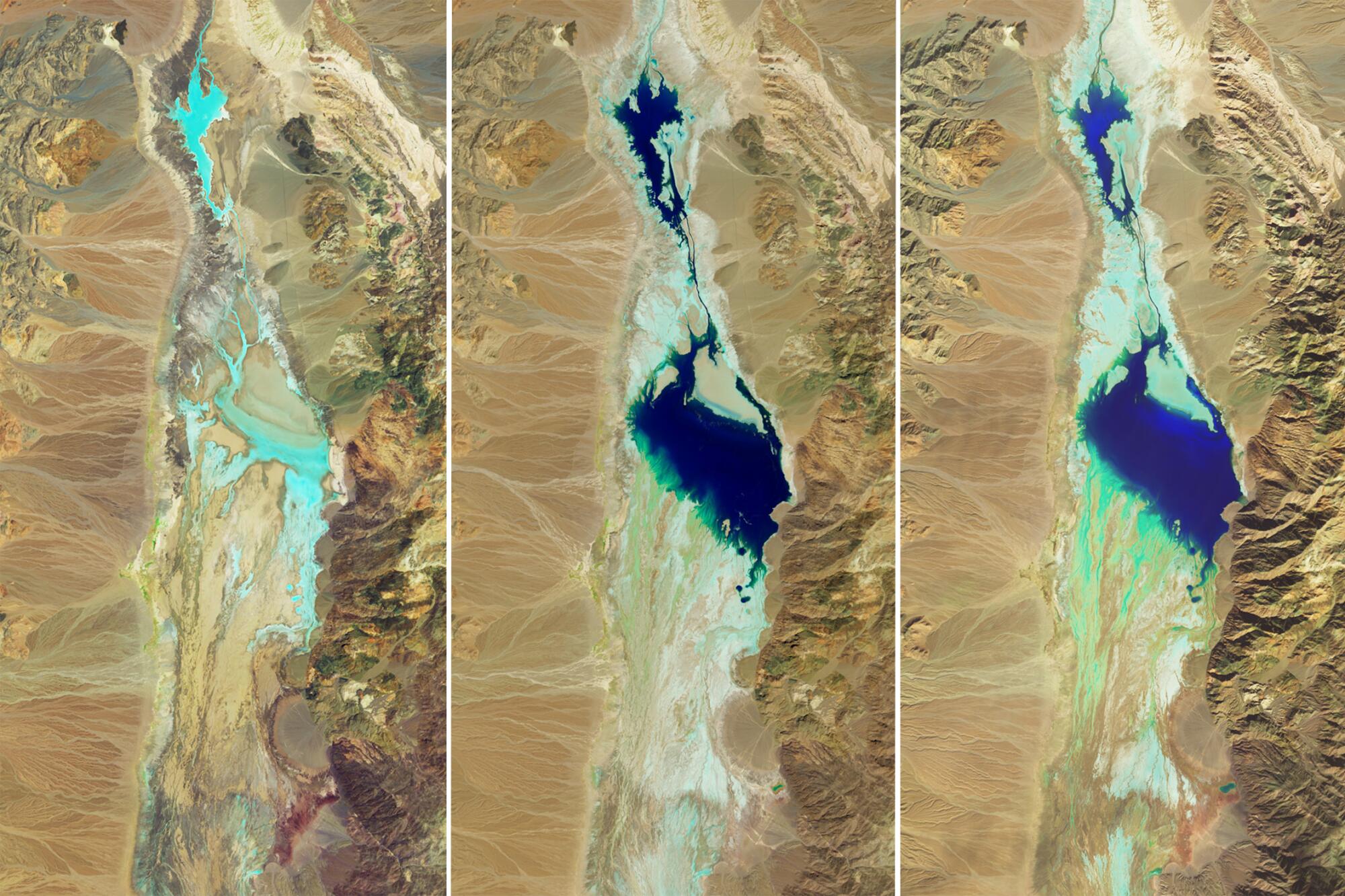

As of mid-February, the lake — referred to as Lake Manly — was 6 miles long, 3 miles wide and up to 2 feet deep in some places, according to Wines.

Spreading ethereally over the lowest region in North America, the floodwaters reflect mountains that rise around it, including snow-capped Telescope Peak to the west. The lake is shallow, but deep enough to buoy a small watercraft for the time being.

Aggressive and impactful reporting on climate change, the environment, health and science.

“It will probably be deep enough to kayak for maybe another couple weeks, possibly longer than that,” said Wines, who has worked as a ranger in the park for nearly 19 years. “But if anyone’s procrastinating, they [should] get out here now.”

Efforts to restore river floodplains are expanding in California. Making space for water is increasingly seen as a natural solution for floods and droughts.

The lake made an appearance last year after the unseasonable arrival of Hilary — a hurricane that degraded to a post-tropical low by the time it hit Southern California. Before that, waters last covered the typically dry, crusty basin in 2005, officials say.

In August 2023, Hilary dumped 2.2 inches of rain on the park — more than the barren landscape typically sees in a year. The water collected in Badwater Basin, which is 282 feet below sea level. However, most people couldn’t see it right away because “every road into the park was destroyed,” Wines said. When the first roads opened about two months later, the lake had already shrunk.

Water levels continued to recede in the fall and winter, but the lake didn’t totally evaporate as park officials had predicted. Then, early this month, an atmospheric river filled it back up, dumping 1.5 inches between Feb. 4 and 7. In the last six months, the park has received 4.9 inches of rain, or about 2.5 times its average annual rainfall, according to the National Park Service.

Wines estimates that the lake doubled in size after the deluge earlier this month.

Unlike last year, park visitors can essentially drive right up to the time-limited attraction. Most of the paved roads in the park are open, including Badwater Road, which can be taken to the lake area. (There’s no place to rent a kayak in Death Valley, so those interested in going out on the water need to bring their own.)

Satellite images released by NASA illustrate the ephemeral lake’s dramatic transformation between early July and mid-February. The three-image series compares the arid landscape before the arrival of Hilary to a “more-waterlogged state following each major storm,” the space agency said in a news release.

Capturing rainfall is only one part of the L.A. River’s job. It is also a flood control channel that is critical to protecting lives and properties when stormwaters surge.

Death Valley wasn’t always so bone dry. During the Ice Age, a behemoth lake — also called Manly — stretched across Badwater Basin and reached to a depth of 600 feet, according to Wines. It vanished about 10,000 years ago, but a smaller version manifested itself about 3,000 years ago during a period known as the Little Ice Age.

The heavy rain so far hasn’t led to a surge in wildflowers, a phenomenon referred to as a superbloom. Wines said the region needs to receive consistent rain throughout the fall and early winter to set the stage for such an event. However, it was relatively dry between Hilary and the storms of early February.

Typically, signs of an intense bloom are evident by late January before peaking in March.

There’s a 55% chance La Niña could develop between June and August, and a 77% chance it could develop between September and November, NOAA said.

“I see some flowers in a few spots when I go out hiking or driving around, but it’s not a carpet of color,” she said.

Throngs of visitors visit the park during the relatively cool period between February and early April, and this year appears to be no different. On Sunday, Wines said 3,500 people passed through the Furnace Creek Visitor Center in the park, marking the busiest day measured in that spot.

Toward a more sustainable California

Get Boiling Point, our newsletter exploring climate change, energy and the environment, and become part of the conversation — and the solution.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.