Monterey Bay desalination project is approved despite environmental injustice concerns

SALINAS, Calif. — In a decision that sheds harsh light on the state’s commitment to environmental justice amid growing drought anxiety, the California Coastal Commission has granted conditional approval to a controversial Monterey Bay desalination project that even the commission’s own staff said would unfairly burden a historically underserved community.

“This is a really, really tough decision,” Commission Chair Donne Brownsey said during a heated 13-hour hearing Thursday. “I, like most of the commissioners up here, struggled with this. But I read everything … I talked to everybody ... and I feel like this is the right place to land.”

California American Water, an investor-owned utility, has proposed building a more than $330-million desalination project on a former sand-mining site in Marina, a small city where one-third of the community is low-income and many speak little English. The plant would convert as much as 6.4 million gallons of oceanwater to drinking water per day that would then be piped to neighboring cities and businesses.

The proposal drew testimony from more than 350 speakers and was regarded by many as the first major test of the commission’s new power to consider potential harms to underserved communities in addition to environment impacts. In a 157-page report, commission staff said the proposal presented “the most significant environmental justice concerns the Commission has considered since it adopted an Environmental Justice Policy in 2019.”

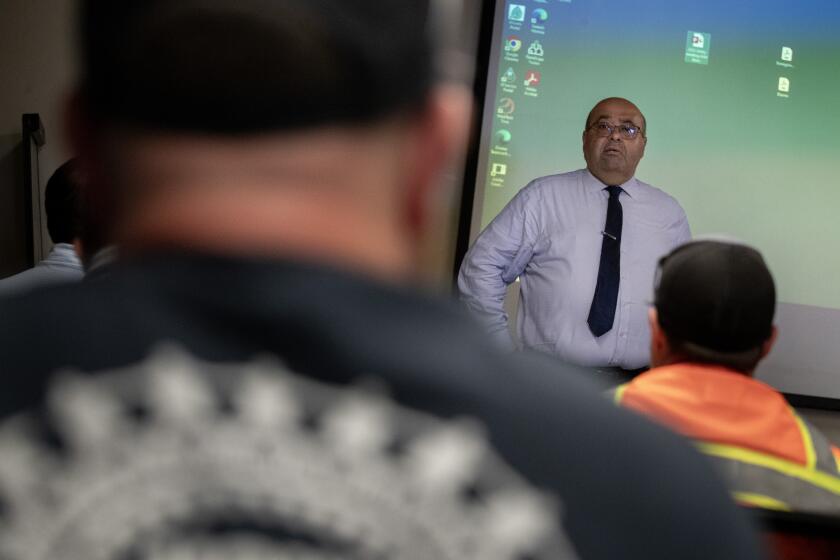

The commission issued its ruling in a Salinas chamber packed with lawyers, local water officials, labor groups, tribal leaders, and residents from across the region. Many noted the presence of Wade Crowfoot, Gov. Gavin Newsom’s highest-ranking appointee on natural resources, who spent his entire day at the hearing and gave opening remarks emphasizing the need to diversify California’s water supply.

The state report paints a stark picture of California’s escalating climate crisis and documents wide-ranging effects on weather, water and residents.

Amid this backdrop of repeated calls by the Newsom administration to fast-track desalination, commissioners examined water demand projections, local groundwater impacts and other water supply concerns. The heart of the debate, however, focused on whether it was acceptable to continue saddling some communities but not others with the burden of industrialization.

Marina, with a population of more than 22,000, is already bearing the brunt of a regional landfill and sewage plant, as well as a sand mine that has dredged away the coast for more than a century. Many speakers also questioned the proposal’s economics, decrying reports that Cal Am’s treated seawater would run almost $8,000 per acre-foot — a shockingly expensive price tag that could burden ratepayers across the Monterey Peninsula.

Commissioners, who voted 8 to 2, acknowledged these concerns and sought to remedy the situation by demanding a strict set of conditions — including guaranteed protection of low-income ratepayers, intense monitoring for any potential groundwater damage, and extensive restoration of precious dune habitat. They also ordered Cal Am to give Marina $3 million and a full-time employee for 10 years to develop more public amenities for the community.

Residents of Marina, however, said this felt like a slap in the face.

“Essentially, they’re saying that environmental justice can be negotiated for $3 million,” said Kathy Yaeko Biala, who has spent many late hours speaking up for her community. “It becomes monetary, and not a principle to uphold.”

Caryl Hart, one of the two commissioners to vote against the project, echoed this sentiment and said Thursday’s vote was a failure of the values the commission stood for.

“You don’t buy off environmental justice concerns,” she said. “I just don’t understand why we’re plowing ahead in this way... this is a violation of our environmental justice policy, in my opinion.”

Water politics is rarely easy, but along Monterey Bay, it’s particularly fraught: The region, isolated from state and federal aqueducts, has limited water options. A few communities like Marina tap their own groundwater, but most rely on Cal Am, which has pumped the Carmel River for decades.

But the river, where 10,000 steelhead trout once spawned, has suffered from the region’s water demands. Cal Am was pumping more than three times its legal limit and by 1995, the State Water Resources Control Board had ordered an end to the overdraft — a deadline that was extended until December 2021.

A number of alternate supply projects have been proposed over the years, including a new dam and a desalination plant at the Moss Landing power plant. Voters rejected the dam’s financing plan, and environmentalists balked at all the marine life that could be harmed by sucking water directly from the ocean.

So Cal Am tried again with the Monterey Peninsula Water Supply Project: a smaller desalination plant that would use a slanted well technique that does not draw water from the open sea. They picked a new site — a sand mine in Marina that recently closed.

This downsized project relies on a new public recycled water project to fulfill the demand gap. In the last two years, facing mounting controversy, the company also agreed to build the project in phases and downsize the overall footprint even further — from six slant wells to four.

“We used the best science and engineering available. We thoroughly vetted everything and answered every objection we heard — and we took what we heard, and we made changes to the project to make it better,” said Kevin Tilden, the company’s president.

Cal Am also offered to sell some of the desalinated water to Marina (which the community said added insult to injury), and it worked out an agreement to provide water at a reduced rate to Castroville, a small community of farm workers on the brink of collapse.

“The average household income here is $35,000, and I’m not sure if that counts the fact that there’s usually two families squeezed into a house,” said Eric Tynan, general manager of Castroville’s Community Services District, who noted, with clear panic in his voice, that his community just lost its best well to seawater intrusion.

Critics say Castroville got played — a false pitting of one underserved community against another. That’s what happens when a big water company controls so many pieces of the chessboard, said Melodie Chrislock, who’s spearheading a public effort to buy out Cal Am to put a stop to the exorbitant cost of water.

Even the most conservative estimates suggest the average ratepayer will pay at least $564 more a year to finance the desal project. But the final cost burden — and whether the water is even needed — remains unknown, pending a final determination by the California Public Utilities Commission next year.

“There’s something going on politically here that really smells,” said Chrislock, a longtime resident of Carmel, who said it felt premature to have the coastal commission sign off on the project before the CPUC’s determination.

Chrislock, along with many others on Thursday, pointed to the new recycled water project, Pure Water Monterey, as a more equitable and environmentally conscious way of meeting the region’s water needs for at least the next three decades. Expanding this other project — a joint effort by local public agencies — would also be much cheaper.

Cal Am declined to provide up-to-date estimates, but public water officials calculated the desalinated water could cost at least $7,900 per acre-foot, or per 325,851 gallons. (Compare this to the $1,700 per acre-foot cost of the publicly owned Doheny desalination project, which the coastal commission approved last month. Even Poseidon Water’s controversial proposal in Huntington Beach, which the commission unanimously rejected in May, would’ve cost less than half, at $3,000 per acre-foot.)

Recent filings to the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission also show that Cal Am has already incurred $206 million in aggregate costs related to the project.

After hours of intense debate Thursday, coastal regulators have rejected Poseidon Water’s proposal to build a desalination plant in Huntington Beach.

State Assemblyman Mark Stone (D-Scotts Valley), who represents all the communities at stake and opposes the project, noted that “Cal Am, as an investor-owned utility, owes its allegiances to its investors: It has to grow, it has to make money, it has to be profitable.”

Some commissioners, concerned with these unanswered cost questions, made clear that the project could not break ground without the CPUC’s final authorization that the water was indeed needed.

Back in Marina late Thursday, residents were visibly worn out from trying to keep up with Cal Am’s more sophisticated lobbying.

“I am suffering,” said Bruce Delgado, Marina’s longtime mayor, whose voiced cracked with emotion talking about all the families, schoolteachers and students who spent yet another day pleading their case to the powers that be.

Delgado said the city is considering its next options. Marina has already sued Cal Am, and local leaders recently broached the idea of having their own water district pipe water to Castroville. Their two communities, both struggling, should never have been pitted against each other, he said.

For Monica Tran Kim, who juggles four jobs to make ends meet, making it to the meeting this week meant sacrificing more than 12 hours of work. But she felt an immense duty to speak up for the city’s large refugee community.

Kim, whose parents fled Vietnam and forged a new life fishing off Marina’s open shore, said many have been reluctant to speak up against a company as politically powerful as Cal Am. She thinks often of the hardworking families that had been historically run out of Pacific Grove and other more wealthy cities nearby.

“First it was land, now water,“ she said. “It’s a historical repeat of people in power taking what’s valuable from a community that they don’t see as deserving — from a community that is vulnerable.”