In California’s dusty oil country, Ukraine war brings faint hope of keeping wells flowing

TAFT, Calif. — Here amid the dusty hills and deserted main streets of California’s oil country, the last three years have delivered “one kick in the gut after another,” some say.

The coronavirus, wildly fluctuating crude prices, lingering surface spills, Gov. Gavin Newsom’s pledge to transition to a “carbon-neutral” economy and the recent closure of two local prisons have left many wondering just what the future has to offer in this sere corner of western Kern County.

In recent days however, that grim outlook has given way to a potent mix of hope, anger and desperation following President Biden’s ban on the importation of Russian oil.

The executive order, which is intended to undermine President Vladimir Putin’s ability to wage war in Ukraine, has contributed to soaring gasoline prices. It has also given oil industry advocates a new cudgel with which to fight California’s pumping restrictions.

“We’re ready to meet this God-given opportunity with expertise and a critical natural resource we’ve got plenty of,” said Dave Noerr, mayor of Taft and a veteran oilman. “But we’re not being allowed to do what we do best for what California needs most — local oil.”

In the fields surrounding such historic oil centers as Taft and McKittrick, a labyrinth of steam pipes, fuel lines, diesel power generators and dirt roads weave amid countless pump jacks. The air here smells like crankcase oil — as it has for decades — but there is far less activity now than there was just three years ago, and local communities are feeling the pinch.

State oil and gas regulators have denied most new permits to use hydraulic fracturing, commonly called fracking, and similar extraction technologies since 2019, when Newsom began calling for plans to phase out oil production in California, citing the increasingly harmful effects of global warming.

His actions raised ire in petroleum company boardrooms, enraged Kern County officials and left small-town officials at the southern end of the San Joaquin Valley grappling with shrinking tax rolls.

Newsom has since been named a defendant in lawsuits filed by Kern County and the Western States Petroleum Assn., which accuse him of causing “irreparable harm” to roughly 23,900 people who, directly or indirectly, depend on Kern County’s 76 active oil fields to earn a living. The lawsuits want a judge to declare that his actions are “are null and void and exceed the bounds of law.”

But now, some see the Russian oil ban as their last, best hope of forcing the state to expand production.

State and federal lawmakers backed by the oil industry have spent the last week pounding Newsom’s anti-oil stance.

In a letter sent to Newsom a week ago, House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy (R-Bakersfield) said, “it is critical that we actively work to replace Russian oil imports” with “cleaner American energy that can be produced in California by Californians.”

“Taking action to increase energy production at home,” he said, “would also increase domestic energy supplies — potentially helping blunt increases in already-soaring gas prices seen across our state.”

Locals ask how a country that still imports millions of barrels of petroleum per day — from sometimes hostile suppliers — can ignore a place like this.

For them, a small uptick in production on existing oil field operations over the last week prompted by the rising value of oil and gas commodities has brought a measure of relief, and hope.

But viewed at close range, the robustness of what Noerr described as “a bump in production of about 5% to 10%” looks like a fragile boomlet.

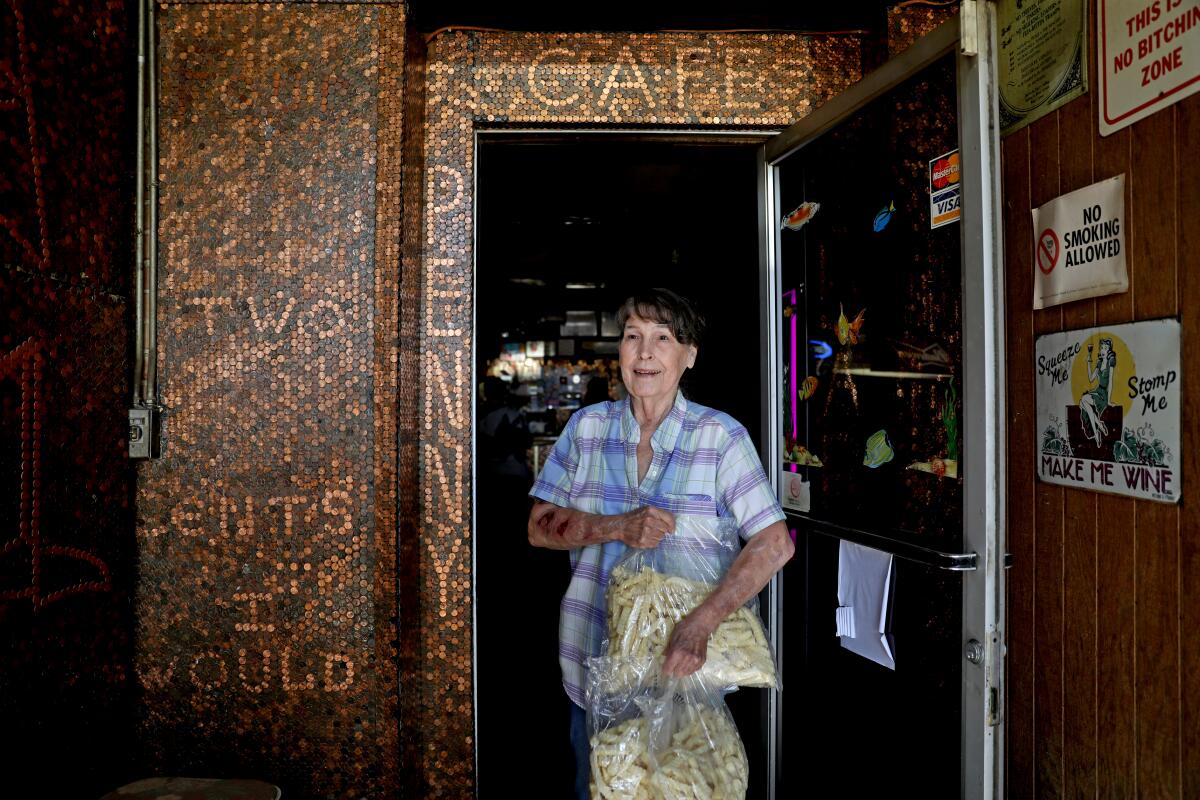

For instance, it has meant larger crowds of hungry oil field workers at Mike & Annie’s McKittrick Hotel, Penny Bar & Cafe, a watering hole in a town with a population of about 145 people about 15 miles northwest of Taft.

“Things have been picking up a little bit,” said Annie Moore, co-owner of the business on scenic Highway 33 featuring more than a million pennies glued to the bar, floors, walls, television and entrance. “We really needed that.”

The big question now is whether it will grow into something lasting and beneficial on streets that embody many of the most attractive attributes of small-town Americana, along with bronze oil rigs and other pieces of machinery erected as reminders of their economic roots.

Oil drilling in Kern County dates to the 19th century, with the first field developed in 1898.

Just three years ago, Kern County ranked first among California’s oil-producing counties, producing 119 million barrels of oil, about 71% of the state’s production. In 2020, the most recent year available, production had dropped to 103 million barrels, according to the data service DrillingEdge.

In 2020, for the first time in California history, Newsom issued an executive order directing the California Environmental Protection Agency and California Natural Resources Agency to “expedite” the “closure and remediation of former oil extraction sites as the state transitions into a carbon-neutral economy.”

A year later, he directed the California Air Resources Board to evaluate plans to “reduce or eliminate demand for fossil fuel in California and end oil extraction in our state.”

Even with a ban on imported oil, the drive to phase out fossil fuel emissions remains an urgent priority for many.

Last month, a United Nations climate report said that people’s lives and Earth’s ecosystems are at increasing risk of catastrophe if nations fail to quickly reduce emissions of planet-heating gases.

As global warming continues to amplify deadly heat waves, intense droughts, floods and devastating wildfires, researchers from 67 countries called for urgent action to address the crisis. They said many of the dangerous and accelerating effects can still be reduced, depending on how quickly the burning of fossil fuels and emissions of greenhouse gases is curbed.

Western Kern County’s oil industry has endured downturns before. But the current decline differs because it has coincided with shifting political winds, the rush to develop alternative sources of energy, the COVID-19 pandemic, and rising concerns about toxic emissions, leaks and seeps from oil and gas production.

A huge seep in Chevron Corp.’s Cymric Oil Field, just outside McKittrick, unleashed a gusher of troubles for the region in 2019. More than 1 million gallons of oil and brine oozed from a well, filling a dry creek and creating a hazardous black lagoon.

When Newsom went to the spill site, the sarcastic response heard across town was, “There goes the neighborhood.”

Chevron is still trying to permanently stop the seepage. On Friday, the company described its condition as “stabilized,” with flow rates that are “95% lower today than in July 2019.”

The seep was only one in a series of recent setbacks, locals say.

In 2021, as Newsom was attracting support for his anti-oil stance, a state prison and a federal prison closed in Taft, causing the sudden loss of more than 400 local jobs.

“Losing both prisons in one year — on top of everything else — was devastating for this town,” said Michael Long, 67, owner of Black Gold Brewing Co. in Taft, where patrons are offered an assortment of Thai food, craft beers, guns and ammo.

“To make up for the economic losses,” added Long, a burly man who is also publisher and executive editor of the Taft Independent Newspaper, “the residents of Taft voted in favor of a 1% sales tax, which kicks in this month.”

Beyond all that, it has been painfully disappointing to watch oil industry investments migrate to states with easier extraction rules and higher profit margins, such as New Mexico and Texas, since Russia marched into Ukraine.

Taft is at a crossroads. “We need more housing and diversification of jobs,” Long said as he eyed the main drag through Taft, a melange of storefronts, many blemished by chipped paint and boarded-up windows.

That won’t be easy. But Noerr enthusiastically insists that the squeeze at the pump as gas prices continue to rise has presented Kern County’s ailing oil industry with an opportunity to rise to the myriad political, economic and technical challenges on the horizon.

He tells anyone who will listen about ambitious proposals to transform the area into a proving ground for new, less environmentally harmful and more efficient refinements of extraction technologies, maybe even carbon capture and storage enhancements.

On a recent weekday, Noerr brought his black, 425-horsepower pickup to a stop on a two-lane road flanked by oil rigs and steam pipes.

“Here’s the deal,” he said, turning to a reporter. “We don’t have a giant river, scenic coastline, bustling harbor or a major railroad line. We are a relatively small area surrounded by 10,000 wells.

“All we want,” he said, “is a chance to keep the door open to new opportunities.”