Thanks to climate change, hurricanes pummel land longer

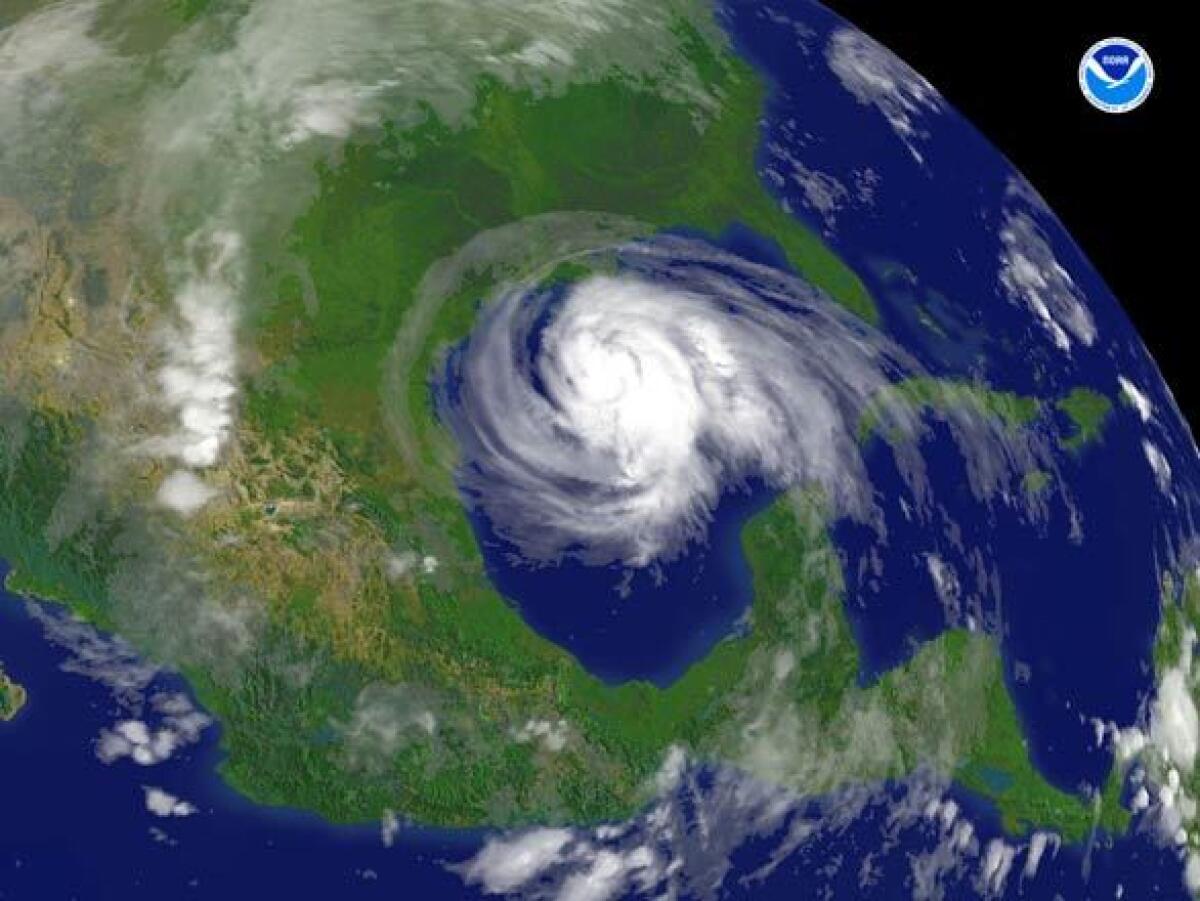

Hurricanes are doing more damage to inland areas because they’re lasting longer after making landfall, and warmer ocean waters due to climate change are the likely cause, according to new research.

With Hurricane Eta further threatening Florida and the Gulf Coast in coming days, the study’s lead author warned of more destruction away from the coast than in the past.

The new study examined 71 Atlantic hurricanes that made landfall since 1967. In the 1960s, hurricanes’ wind strength declined by two-thirds within 17 hours of landfall. Now, it generally takes 33 hours for storms to weaken to that same degree, according to the study in Wednesday’s journal Nature.

Our oceans. Our public lands. Our future.

Get Boiling Point, our new newsletter exploring climate change and the environment, and become part of the conversation — and the solution.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

“This is a huge increase,” study author Pinaki Chakraborty, a professor of fluid dynamics at the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology in Japan. “There’s been a huge slowdown in the decay of hurricanes.”

Hurricane Florence, which in 2018 caused $24 billion in damage, took nearly 50 hours to decay by about two-thirds after making landfall near Wrightsville Beach, N.C., Chakraborty said. Hurricane Hermine in 2016 took more than three days to lose that much power after hitting Florida’s Apalachee Bay.

As the world warms from human-caused climate change, inland cities like Atlanta should see more damage from future storms that just won’t quit, Chakraborty said.

Those inland cities will need to prepare, added University of Miami hurricane researcher Brian McNoldy, who wasn’t involved in the study.

“If their conclusions are sound, which they seem to be,” he said, “then, at least in the Atlantic, one could argue that insurance rates need to start going up and building codes need to be improved ... to compensate for this additional wind and water destructive power reaching farther inland.”

There’s less research on what hurricanes do once they make landfall than when they’re out at sea, so Chakraborty said he was surprised when he saw a noticeable trend toward longer decay.

Before he began the study, Chakraborty said he figured the decline in power shouldn’t change over the years even with man-made climate change, because storms tend to lose strength when cut off from the warm water that fuels them.

It stops going, like a car that runs out of gas, he said. But hurricanes aren’t running out of gas as much, especially in the last 25 years, when the trend accelerated, Chakraborty said.

To find out why, he charted the ocean temperature near where the hurricane had traveled and found it mirrored the decay trend on land.

Researchers then simulated hurricanes that were identical except for the water temperature. Seeing that the warmer-water storms decayed more slowly, they reached their conclusion: The slowdown of hurricane decay resulted from warmer ocean-water temperatures, which are caused by the burning of coal, oil and natural gas.

“That’s an amazing signal that they found,” said National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration climate and hurricane scientist Jim Kossin, who wasn’t involved in the study but reviewed it for Nature.

This study joins previous research, much of it by Kossin, showing that tropical systems are slowing down more, becoming wetter, and moving closer to the poles. Perhaps most ominously, studies also show that the strongest hurricanes are getting stronger.