Exide may be allowed to abandon toxic battery recycling plant and massive cleanup bill

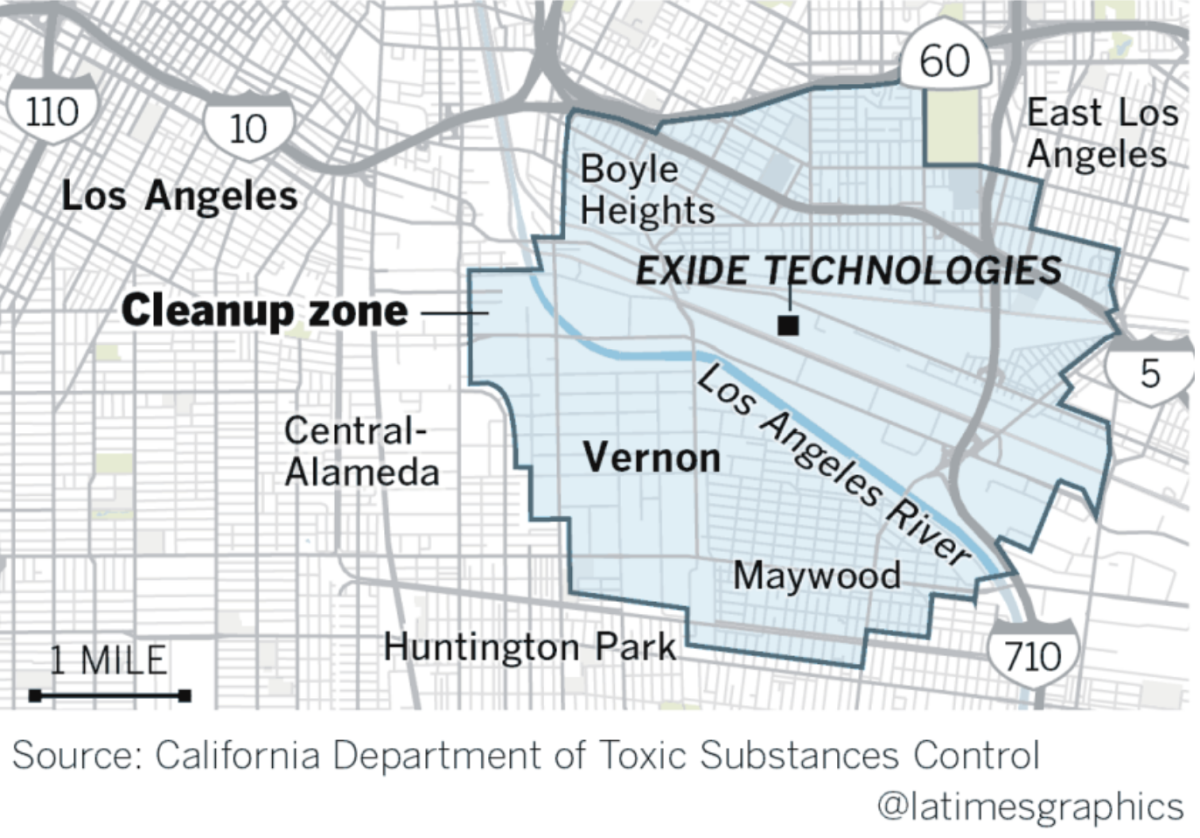

For decades, families across a swath of southeast Los Angeles County have lived in an environmental disaster zone, their kids playing in yards polluted with brain-damaging lead while they wait on a state agency to remove contaminated soil from thousands of homes.

Now, the cleanup faces even greater uncertainty. A bankruptcy plan by Exide Technologies, which operated the now-closed lead-acid battery smelter in Vernon that is blamed for the pollution, would allow the site to be abandoned with the remediation unfinished.

The Trump administration, through the U.S. Department of Justice and the Environmental Protection Agency, has agreed not to oppose Exide’s plan, meaning that state taxpayers would be left with the bill for California’s largest environmental cleanup, which already stands at more than $270 million.

The proposal has sparked outrage among state regulators, elected officials and community groups in the largely working-class Latino neighborhoods around the plant. They are demanding the plan be scrapped before a court hearing scheduled for Thursday.

In a letter to U.S. Atty. Gen. William Barr, seven state lawmakers representing the affected neighborhoods said Exide must be held accountable for causing “immeasurable damage” to surrounding communities. “Unfortunately for our residents, unlike Exide, there is no legal process that allows them simply to erase the lead pollution from their bodies.”

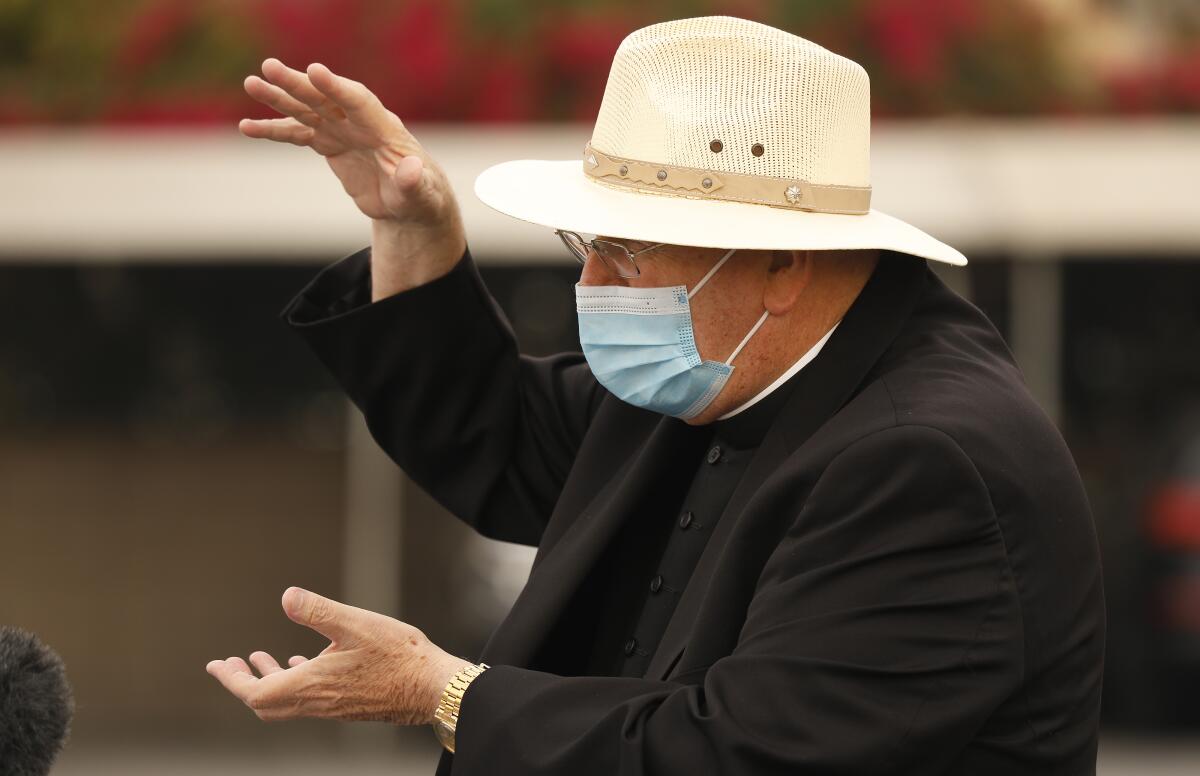

Msgr. John Moretta of Resurrection Catholic Church in Boyle Heights implored the Department of Justice to “not abandon this community to the trash that Exide left here.”

The Department of Justice and the EPA did not answer questions from The Times but announced they will hold a virtual public meeting at 4 p.m. Tuesday “to listen to the community’s concerns.”

“We are evaluating public comment received, as called for in that proposal,” the two agencies said in nearly identical statements. “Because the Exide matter remains in active litigation and before the Bankruptcy Court, other statements about the proposed settlement will be made in that forum.”

Exide did not respond to a request for comment. In the past, the company has argued that it is not responsible for lead contamination beyond the boundaries of the Vernon facility, which it took over in 2000. It has blamed other sources for the residential contamination, including neighboring industrial facilities and lead-based paint.

And in court filings, the company has argued that it has fulfilled its cleanup obligations and accused the state of seeking to improperly impose hundreds of millions of dollars in liability for “alleged off-site residential contamination.”

A 2015 deal struck between the U.S. attorney’s office for the Central District of California and Georgia-based Exide was supposed to prevent such an outcome. In it, the company admitted to years of environmental crimes, escaping criminal charges in exchange for permanently closing the Vernon facility, demolishing it and cleaning up the pollution.

At the time, the U.S. attorney’s office defended its non-prosecution agreement as a way to ensure a timely cleanup without leaving taxpayers with the bill. If the company failed to comply with the cleanup agreements at any point in the following 10 years, officials argued, it would face the “hammer” of criminal prosecution for those crimes.

That hasn’t happened, despite the state’s determination last year that the company was in violation of the agreement.

Activists, who have long questioned the company’s deal with federal authorities, said the outcome was foreseeable.

“I’m not surprised that Exide has continued to find ways to avoid paying for the cleanup,” said Idalmis Vaquero, a member of the group Communities for a Better Environment who lives in a Boyle Heights public housing complex within the cleanup zone that has not yet been treated for lead contamination. “I’m also really frustrated by the incompetence, slow cleanup and the lack of legal power that [the Department of Toxic Substances Control] is willing to exercise.”

California regulators blame the plant, about five miles from downtown L.A., for spreading lead dust over half a dozen communities up to 1.7 miles away where more than 100,000 people lived. But the state let the facility operate without a full permit for more than three decades. It also did not require the company to set aside adequate funds to clean up its pollution, even as it repeatedly ran afoul of environmental rules on hazardous waste and released illegal amounts of lead and other toxic pollutants into the air.

People in surrounding neighborhoods pushed for years for the plant’s closure only to wage more battles with state bureaucrats to get their property cleaned of the lead contamination left behind. Lead is a potent neurotoxin that can cause learning disabilities, lower IQs and other permanent developmental and behavioral problems in children, even in tiny amounts.

“Lead exposures in communities around Exide remain widespread,” said Jill Johnston, a professor of preventive medicine at USC. “Without active remediation, this large source of lead will continue to pose a threat to the health of surrounding communities.”

The state Department of Toxic Substances Control has removed lead-tainted soil from about 2,000 residential properties since 2014. But thousands more properties with lead contamination above state health limits have yet to be cleaned, and the project has long been plagued by delays and accusations of mismanagement.

Allison Wescott, a Toxic Substances Control spokeswoman, blamed the predicament on the company, saying that “ever since the contamination was discovered, Exide has worked to evade its full responsibility to Californians.”

“And now it is attempting to use the bankruptcy process to abandon the Vernon facility completely,” she said.

Exide filed for bankruptcy protection in May with plans to liquidate its assets across several states.

After negotiations earlier this year, California was presented with a settlement proposal last month that asked the state to accept $2.5 million in exchange for releasing the company from all liability, state officials said. California refused to sign on, but the company moved forward with a “nonconsensual” plan that would remove liability and allow for abandonment of the site.

The proposal was released publicly on Sept. 25, providing only eight business days for community members to submit comments.

Residents in the neighborhoods surrounding the plant were aghast.

“They admitted to criminal activity, and still they’re walking away,” said Joe Gonzalez, a retired Boyle Heights postal worker who fought for years to shut down the plant and is now battling the state to rid his yard of lead contamination. “It’s just a long-haul nightmare. And we need officials to stand up for our communities and the harm that we’re suffering.”

Unsettled: Exide | Video by Bethany Mollenkof and Spencer Bakalar

The state filed an objection on Wednesday, pleading with the Bankruptcy Court to deny a plan that “effectively foists all of the risk and costs of the Vernon plant onto the shoulders of Californians and would allow the parties most responsible to walk away from an imminent and substantial public health risk.”

The facility, at 2700 S. Indiana St. in the heavily industrial city of Vernon, has not operated since 2014 but “remains highly contaminated and an ongoing daily risk,” according to the state’s court filing. The main part of the facility is protected by an enclosure made of scaffolding, trusses and plastic sheeting that is not meant to be permanent and “requires daily operation, maintenance, inspections, and monitoring to ensure hazardous materials do not escape ... and further contaminate the surrounding communities.”

Cleaning the closed facility itself will cost between $70 million and $100 million, according to the state.

California officials have for years said they are building a legal case to recoup cleanup costs from the company and any other responsible parties. But it’s unclear what recourse the state will have if Exide’s bankruptcy plan is approved.

Toxic Substances Control “continues its work with the attorney general’s office to hold accountable all parties responsible for contamination from operations of the Exide facility,” Wescott said. She conceded that Exide’s bankruptcy threatens California’s ability to recoup costs, but said the agency “has the steadfast support of state and local leadership necessary to see this cleanup through.”

State Assemblyman Miguel Santiago (D-Los Angeles) criticized the Department of Toxic Substances Control for its “dysfunction and an inability to move quickly.”

“If DTSC had taken swifter legal action against Exide, they would have been in a stronger position in the bankruptcy,” Santiago said. “All California communities are in danger of becoming the next Exide disaster if we don’t have an agency that moves at lightning speed as an aggressive bulldog against polluters.”

California Secretary for Environmental Protection Jared Blumenfeld defended the state’s actions, saying, “We’ve tried at every turn” to hold Exide accountable.

The situation is complicated by the immense scope of the contamination and the fact that the company is liquidating, which all but eliminates the prospects of generating future cleanup funds, said Sean Hecht, an environmental law professor at UCLA Law School. But one thing the bankruptcy process cannot absolve the company of is criminal liability, he said.

“Theoretically the Department of Justice could come after Exide for the felonies that it’s already admitted,” he said. “But what would that accomplish in terms of actually getting funding for the cleanup? Ultimately the money isn’t there, and that’s what the problem is now.”