Want jobs and clean energy? This overlooked technology could deliver both

Sunrise Powerlink carves a twisting path through the deserts and mountains of Southern California, skirting the U.S.-Mexico border and cutting through a national forest on its 117-mile path from the rural Imperial Valley to urban San Diego County.

Critics fought hard to stop Sunrise Powerlink from getting built. They said the $1.9-billion transmission line would saddle energy consumers with unnecessary costs, degrade sensitive wildlife habitat and interrupt a series of gorgeous landscapes.

But a decade later, the project is serving its intended purpose: bringing solar and wind power to city dwellers.

“You could have all the renewable energy in the world. But if you don’t have the transmission lines, you have nothing,” then-Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger, a Republican, said at the groundbreaking ceremony for Sunrise Powerlink in 2010.

Your guide to our clean energy future

Get our Boiling Point newsletter for the latest on the power sector, water wars and more — and what they mean for California.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Today, the United States is buckling under the weight of a worsening pandemic that has claimed more than 127,000 lives and put an estimated 30 million Americans out of work.

Building more power lines wouldn’t stop the spread of COVID-19. But energy experts say investing in transmission would put people back to work and help urban areas across the country ditch fossil fuels. The burning of those fuels not only drives the climate crisis, but generates lung-damaging air pollution that has been linked to greater likelihood of death from the coronavirus.

What makes transmission so useful?

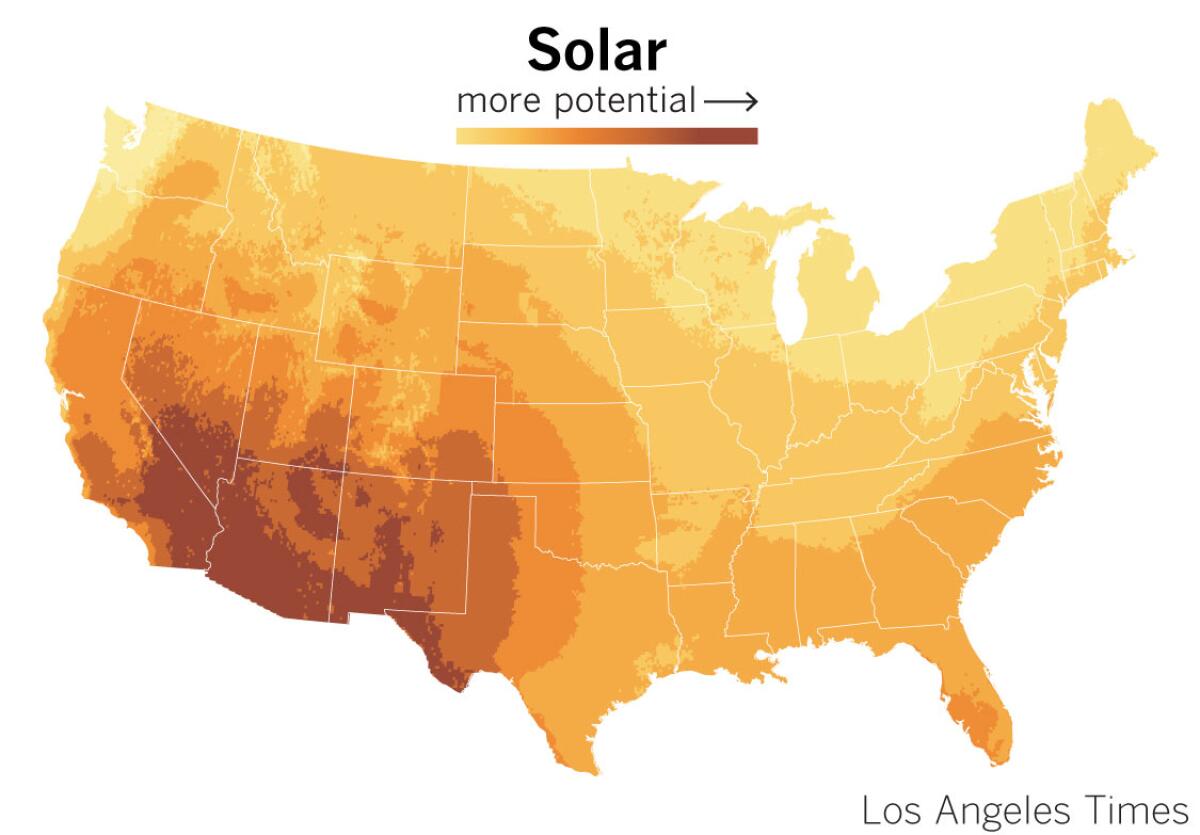

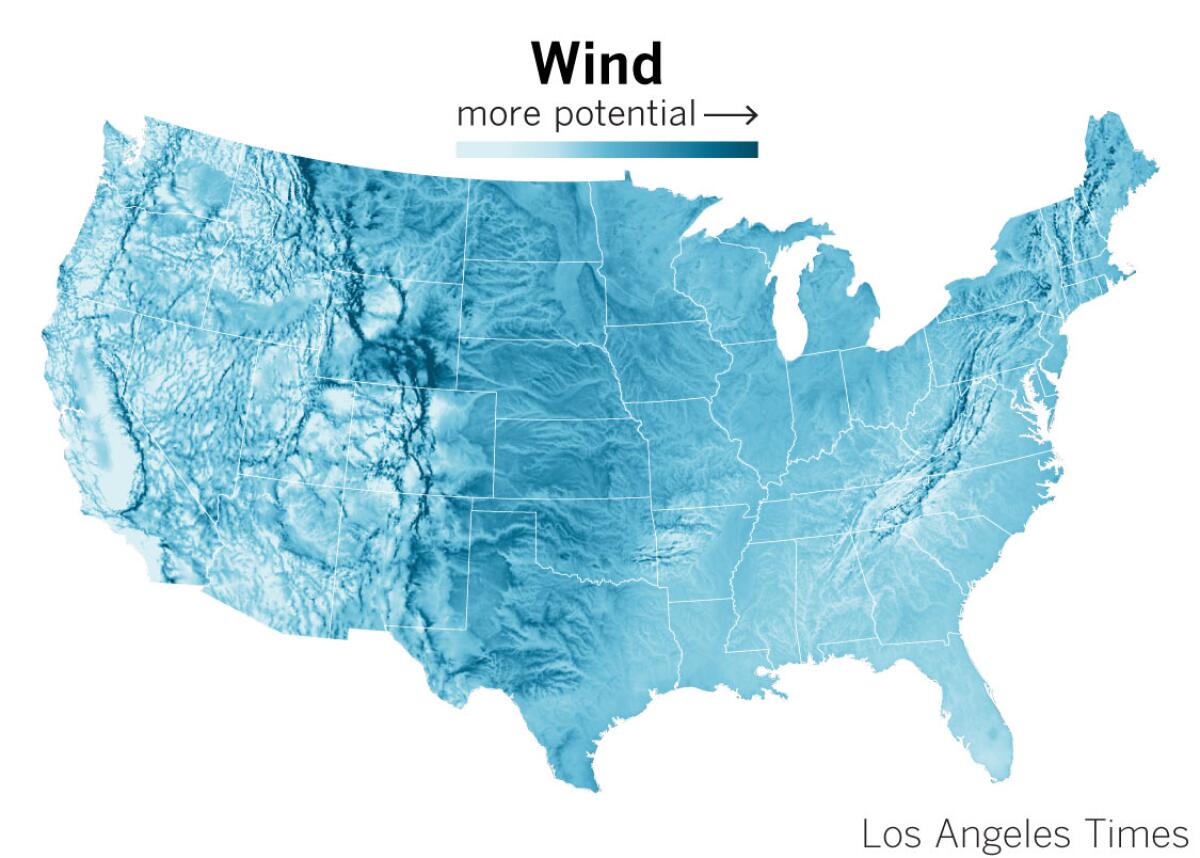

It’s a matter of geography: Rural areas with powerful winds or abundant sunshine — such as California’s Imperial Valley — are the easiest places for companies to build facilities that generate lots of cheap, clean electricity. But those places are typically far from the population centers that use the most energy — hence the need for giant power cords that connect supply with demand.

Removing regulatory obstacles to transmission would fuel economic growth, supporters say. New power lines would facilitate the construction of solar and wind farms, creating high-paying jobs. And private investors would do the financial heavy lifting.

“If you’re looking at infrastructure spending, the electric grid is the most fundamental infrastructure there is,” said Cheryl LaFleur, who served nine years on the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission after being appointed by President Obama.

The American Council on Renewable Energy and Americans for a Clean Energy Grid, both industry groups, in June launched the Macro Grid Initiative, a public relations campaign to promote the benefits of transmission, funded in part by Bill Gates.

A few weeks later, House Democrats unveiled a climate policy plan that recommends building more transmission, with a goal of “modernizing and expanding the electric grid [to] allow more Americans to benefit from low-cost, zero-emission electricity.”

The U.S. electricity supply has gotten cleaner over the last decade as solar and wind energy costs have plummeted, prompting utilities to shut down coal plants. But efforts to accelerate the transition by building power lines have been stifled by opposition from landowners who don’t want lattice towers and wires interrupting their views, and by state and local officials who want to know how proposed transmission corridors will benefit their constituents — and not just the cities at the end of the line.

Conservationists have also worked to block some projects, arguing that poorly sited transmission lines and renewable energy facilities can do serious ecological damage, even as they help to reduce the carbon dioxide emissions fueling the climate crisis.

The Eland solar contract had been delayed due to concerns raised by the city electrical workers union.

Dustin Mulvaney, an environmental studies professor at San Jose State University, sees both sides of the conservation argument.

“There’s obviously really compelling arguments,” he said, for an expanded power grid. But all infrastructure projects — including renewable energy — can take an ecological toll, especially when they’re built on undisturbed public lands in the American West.

As one example, Mulvaney pointed out that ravens, which prey on baby desert tortoises, often nest in transmission towers.

“Whenever you see public lands versus infrastructure, you almost inevitably get these kinds of conflicts,” he said.

Transmission projects are slow by nature. Even with regulatory support, they wouldn’t provide an immediate economic kick-start.

But scientists say humanity must slash fossil fuel emissions quickly and dramatically to limit the damage from worsening heat waves, droughts, fires and other consequences of climate change. And as COVID-19 hobbles global economies, organizations as diverse as the International Monetary Fund and the Sunrise Movement have called for stimulus plans that accelerate the transition away from fossil fuels and create jobs in the clean energy industry, which before the pandemic employed 3.4 million Americans.

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Subscribe to the Los Angeles Times.

Most Republican politicians in Washington, D.C., continue to oppose anything resembling a comprehensive climate plan, even as polls show voters overwhelmingly favor more aggressive federal action. But power grid investments might be different.

“Transmission’s one of those issues that I think there’s broad consensus on. I don’t think it’s a controversial issue,” Neil Chatterjee, a former advisor to Kentucky Sen. Mitch McConnell who was tapped by President Trump to lead the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, said in a recent interview. “We’ve got to have transmission in place to ensure that the grid of the future is there.”

An ‘embarrassing’ history on grid infrastructure

Transmission proponents have been making the same arguments for years, with little to show for it.

During the early years of the Obama administration, the U.S. Department of Energy pledged to “accelerate the permitting and construction” of seven projects that would cross federal lands. The list included a 730-mile power line designed to bring wind energy from the Wyoming plains to cities such as Los Angeles and Las Vegas, and a 290-mile line connecting Idaho and Oregon.

Nearly a decade later, only two of the seven projects have been built.

In “Superpower,” a book published last year, Wall Street Journal reporter Russell Gold chronicled the developer Michael Skelly’s unsuccessful effort to string more than 700 miles of electric wiring from the Oklahoma Panhandle to Tennessee, and bring wind power from the Great Plains to the Southeast. The project was stymied by lawsuits from Arkansas landowners along the proposed route, tepid support from federal agencies and fierce opposition from U.S. Sen. Lamar Alexander, a Tennessee Republican.

“It’s increasingly embarrassing to see how we’ve dealt with infrastructure investments in the United States,” Skelly said in a recent webinar organized by Americans for a Clean Energy Grid. “All we can seem to figure out how to do is build more highways.”

America’s power grid is aging and fragmented. Much of it was built a half-century ago or more, with many lines designed to carry electrons from coal-fired power plants or hydroelectric dams. The western and eastern parts of the country operate on largely separate networks, each of them divided into dozens of smaller jurisdictions. Texas has its own, largely disconnected grid.

The National Renewable Energy Laboratory, a federal research institute, reported in 2018 that building lines across the “seams” of those grids, to better connect different parts of the country, could create as much as $3.30 in benefits for every dollar invested.

Similarly, a 2016 study from researchers with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration found that a national network of high-voltage, direct-current power lines could reduce planet-warming emissions from the power sector 80% below 1990 levels by 2030, while saving consumers $47.2 billion a year — almost three times as much as the cost of the new transmission.

Why the huge cost savings? In part because it’s cheaper to generate solar energy in sunnier places and wind energy in windier places — and in part because the sun shines and the wind blows at different times of day in different parts of the country.

Interior western states, for instance, could import solar power in the evening from California, where the sun sets an hour later. Or California could tap Wyoming’s powerful wind resource as a cheaper, cleaner alternative to firing up gas plants after sundown.

Wyoming wind is the impetus for one of the Obama administration’s long-delayed priority transmission lines that may yet get built.

The conservative billionaire Philip Anschutz — whose holdings include L.A.’s Staples Center and the Coachella Valley Music and Arts Festival — has been developing the $3-billion TransWest Express power line since 2008. It would originate at a massive wind farm Anschutz is building in Wyoming and extend 730 miles to Southern Nevada, where it would connect to the California grid.

Asked why the transmission project has taken so long, Anschutz Corp. executive Bill Miller pointed to a federal environmental review that took about six years; the need to secure permits from two states and 14 counties; and the difficulty of negotiating rights of way with some 450 private landowners along the route. Even now, negotiations continue with a few landowners.

Most developers don’t have the money or the patience for a project like that. Anschutz has already spent more than $400 million developing the transmission line and wind farm, with Miller hopeful construction on TransWest Express will begin next year.

Miller is confident there will be demand for the wind power the company plans to generate. California law calls for 100% climate-friendly electricity by 2045, and other southwestern states are upping their ambition, with Nevada and New Mexico also targeting 100% clean power. Across the country, city and state governments, electric utilities and private companies are setting similar goals.

“In spite of COVID-19 and everything else, we see the whole country leaning in on what’s happening with renewables,” Miller said.

‘It’s not going to be pretty’

In 2011, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission issued rules designed to improve regional transmission planning, spread the costs of new power lines more broadly and open the marketplace to competitive bidders, not just monopoly utility companies.

Those steps were supposed to unleash a wave of transmission development. But they didn’t work.

Answers to what went wrong depend on whom you ask. But there are plenty of ideas for what the federal government might try next, including nine pages of recommendations in the House Democrats’ newly released climate plan. The ideas include funding and technical assistance for states to conduct faster environmental reviews; a dedicated tax credit for transmission investments, such as the one the solar industry enjoys; and building power lines alongside existing railroads and highways, where possible.

The conversation usually comes around to an issue at the heart of American democracy: state versus federal authority.

Unlike natural gas pipelines, whose approval falls solely to the federal government, electric lines can be vetoed by any state along their route. State officials have played a role in derailing major projects, including the Northern Pass transmission line, which would have brought Canadian hydropower to New England but was blocked by New Hampshire regulators.

“NIMBYism is not irrational for many people. They could be bearing the costs, and not getting the benefits,” said David Spence, an energy law professor at University of Texas at Austin.

Congress approved $90 billion for clean energy during the Great Recession, providing a model for how lawmakers might boost the economy amid COVID-19.

Even without a full federal takeover, clean energy advocates say there may be ways to shift some decision-making away from local officials. The House Democrats’ climate plan suggests allowing federal regulators to authorize any clean energy-oriented power lines that were already approved by one or more states, even if other states have rejected the project or withheld approval.

“If we really want to meet our low-carbon future, what has to change, and who has to do what to get there?” asked Julia Prochnik, an energy consultant who previously served as director of western renewable grid planning at the nonprofit Natural Resources Defense Council. “It’s not going to be pretty. It’s not going to be what everyone wants. But we’re all going to gain something.”

Not everyone is embracing transmission.

Some climate advocates would rather see policymakers focus on smaller, more local forms of clean power, such as rooftop solar, batteries housed in garages and community microgrids. Energy economists tend to be less enamored with these “distributed” clean power technologies, arguing they produce more expensive electricity than large-scale solar and wind power plants.

As for big solar and wind farms, Mulvaney thinks they ought to be built on previously disturbed lands. At times, he’s felt frustrated by companies that use climate change to push projects that could harm species such as sage grouse and desert tortoises.

Energy developers, Mulvaney said, “are somewhat taking advantage of people who want to solve the climate crisis.”

“It’s either the tortoise gets it from the land-use change, or it gets it from climate change,” he said. “But I think there are so many more possibilities, and we should be open to what these possibilities are.”

In this week’s climate and environment newsletter, we’re talking dam failures, clean hydrogen and a volcanic eruption.

One possibility is to use existing power lines. Especially in the West, coal-plant retirements are opening up long-distance wires that could be used to bring clean energy to cities. The Los Angeles Department of Water and Power, for instance, is planning to import large amounts of solar and wind energy through a transmission line that currently carries coal-fired electricity from Utah.

Los Angeles is also exploring a partnership with the Navajo Nation to develop solar power on tribal lands, utilizing long-distance wires that previously connected the city with the coal-fired Navajo Generating Station in Arizona, which closed last year.

But reducing emissions fast enough to meet global climate targets is unlikely without at least some additions to the power grid.

“There are those who say we can get there without transmission. Our view is that’s not true,” said Larry Gasteiger, executive director of Wires, an energy industry trade group. “You’re going to need transmission to be part of the solution.”