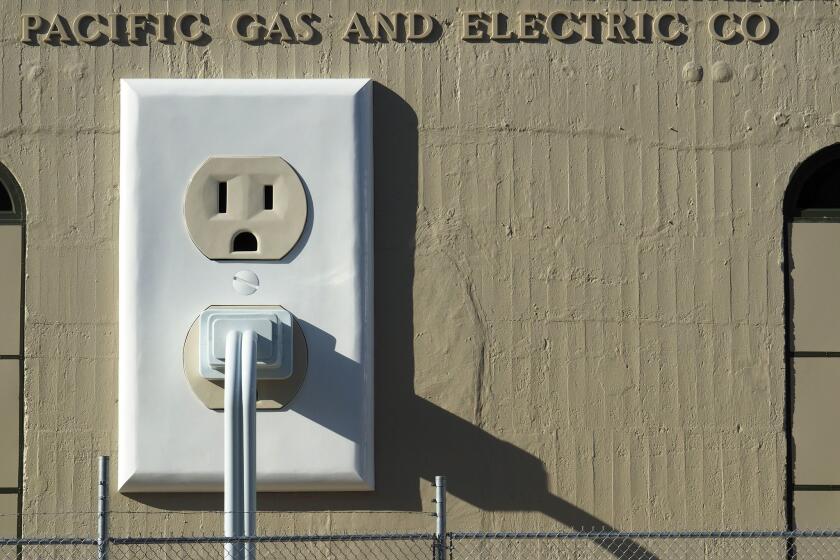

Would a California takeover of PG&E make energy cheaper and safer? Maybe not

Trinity County did in the 1990s what Gov. Gavin Newsom is threatening to do today: It wrested control of the power grid from Pacific Gas & Electric.

The origin story of Trinity Public Utilities District, which now serves several thousand customers in Northern California, is an encouraging precedent for advocates of replacing PG&E with a government-run utility. Trinity customers pay half as much for electricity as PG&E customers do. The public utility’s rates, set by a locally elected board, have hardly changed over the years.

At the same time, Trinity faces several lawsuits and $138 million in claims stemming from a 2017 wildfire — the same type of financial liability that landed PG&E in bankruptcy court. Trinity is contesting those claims, saying its equipment didn’t cause the fire.

As Newsom considers a government takeover of PG&E, Trinity’s experience illustrates both the promise and the perils of public ownership. Although the potential benefits are significant, there’s no guarantee a government entity could provide safer, cleaner or cheaper electricity than the reviled company it replaces.

“It really depends on the governance or management of the utility, whether it be public or private,” said Ed Smeloff, a former board member at Sacramento Municipal Utility District.

Californians have grown increasingly disenchanted with PG&E since 2010, when one of its gas pipelines exploded in the Bay Area city of San Bruno, killing eight people. More recently, the San Francisco-based company’s transmission lines ignited several devastating wildfires, including the Camp fire, which killed 85 people and largely destroyed the Sierra foothills town of Paradise.

Public pressure for some kind of government action has only grown since October, when PG&E intentionally shut off power to millions of people in an effort to prevent more fires.

Nobody has ever transferred a utility as large as PG&E from private to public ownership. But a growing number of state and local lawmakers are calling for a public takeover of the sprawling company, which serves as the power provider for 16 million people across a vast territory stretching from Redding in the north to Santa Barbara County in the south.

Proponents say a publicly owned PG&E would offer lower rates because it wouldn’t have to generate profits for shareholders and would be more responsive to customers and elected officials. They point to public utilities serving Los Angeles, Sacramento and other parts of California as proof that government can provide safe, clean and affordable electricity.

S. David Freeman, a seven-decade veteran of the energy business, is skeptical.

A self-described “public power guy,” Freeman has led several of America’s largest public utilities, including the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power, Sacramento Municipal Utility District, Tennessee Valley Authority and New York Power Authority. He said replacing PG&E with a public utility wouldn’t solve the company’s toughest challenge: fireproofing rural transmission lines in an era when rising global temperatures and hotter droughts have primed California’s mountains and forests for increasingly devastating infernos.

“It’s all well and good to blame PG&E, and Lord knows I could join that crowd easily,” Freeman said. “But that wouldn’t solve the problem.”

What would a publicly owned PG&E look like?

San Francisco offered to buy PG&E’s power lines in the city for $2.5 billion last year, joining three other government agencies that have made similar offers or are considering forming their own local electric utilities. Separately, a coalition of more than 100 mayors and local elected officials — led by San Jose Mayor Sam Liccardo, and representing more than half of PG&E’s customers — released a proposal to convert the company to a customer-owned cooperative.

State Sen. Scott Wiener (D-San Francisco) joined the fray last week, introducing legislation that would replace PG&E with a private contractor reporting to public management at a new state agency. A seven-member board of directors, elected by the new utility’s customers, would set rates.

The public-private structure is modeled after New York’s Long Island Power Authority, a government agency that contracts with a private firm to operate its electric system. Under Wiener’s bill, a reconstituted version of PG&E — sans current management — could play the contractor role, with California paying the company a fixed fee rather than guaranteeing shareholders a rate of return on their investments. The state agency would be subject to California laws requiring transparency and open meetings.

The California Municipal Utilities Assn., a trade group for public utilities, advised Wiener’s office, although it’s neutral on the legislation. Barry Moline, the association’s executive director, praised the senator’s overall concept while noting that smaller public utilities can respond more nimbly to local priorities.

With a larger entity, “you definitely get the public accountability, but you might not have as much community buy-in,” Moline said.

Newsom has repeatedly threatened to lead a public takeover of PG&E if he determines its restructuring plan doesn’t fundamentally transform the company.

So far, the governor isn’t satisfied. He has criticized the financing element of PG&E’s plan, arguing that it would leave the utility with too much debt to spend billions of dollars on needed safety improvements. He has also called for PG&E to replace its board of directors, and to do more to ensure customers aren’t burdened with big rate increases.

In November, Newsom asked one of his top advisors to begin developing a government-led contingency plan to take over PG&E. But the governor hasn’t released any details, nor has he taken a position on the proposals being floated by Wiener and various city officials.

Newsom has immense leverage over PG&E, at least for the next few months. Under Assembly Bill 1054, which was approved last year, the company must emerge from bankruptcy by June 30 in order to tap a $21-billion fund that will help investor-owned utilities handle claims from future fires.

To exit bankruptcy, PG&E must first persuade the California Public Utilities Commission, whose members are appointed by the governor, to approve its reorganization plan — essentially giving Newsom veto power. Without the governor’s blessing, it would be tough for PG&E to meet the June 30 deadline.

“If PG&E can’t access the wildfire fund, it doesn’t have a private-sector future,” said Michael Wara, an energy and climate law professor at Stanford University.

Organized labor is skeptical

Still, the political barriers to public ownership are immense.

The International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, one of the most powerful lobbying forces in Sacramento, has opposed proposals to take PG&E public. The labor union says a government takeover could result in job losses and diminished benefits for the 20,000 or so employees and contract workers it represents at California’s largest utility.

After Wiener introduced his legislation, IBEW Local 1245 began circulating a two-page flier warning that “STATE TAKEOVER OF PG&E IS EXPENSIVE AND DANGEROUS.”

Wiener’s office says his bill is designed to protect PG&E employees by handing over the utility’s day-to-day operations to a new, privately owned enterprise that could employ the existing workforce and maintain the same benefits. But the union fears its members’ pensions wouldn’t survive the transfer from private to public oversight, since those funds would then be governed by different laws and regulations.

“Our lawyers and our accountants and actuaries have not figured out how you can take an investor-owned pension, transfer those assets to the state and preserve exactly the benefits that people have,” said Tom Dalzell, business manager for IBEW Local 1245.

PG&E could try to block a takeover

Even without opposition from labor, transferring PG&E to public ownership might not be quick, or easy.

State officials hold the power of eminent domain, and the Public Utilities Commission can revoke an investor-owned utility’s license to operate.

But none of that would stop PG&E from fighting back, as it did when Sacramento Municipal Utility District attempted to take over parts of its service territory in the 1930s. PG&E delayed the public utility’s launch for more than a decade, in part by arguing that the government’s offer price for its system didn’t reflect fair market value.

“And that’s when life was far simpler,” said Mike Gatto, a former state lawmaker who led the Assembly’s utilities committee. “There was no such thing as consultants, and lawyers weren’t quite as fancy. And the politics weren’t as harsh as they are now.”

Today, as in the 1930s, PG&E insists it is not for sale.

“While recent proposals for state or municipal ownership of PG&E’s infrastructure are not new concepts, we don’t agree that the outcomes of this type of framework will benefit customers, taxpayers, local communities, the state or our economy,” company spokesman James Noonan said in an email.

California voters want to see major changes at PG&E as state leaders grapple with the best path forward for the state’s largest utility.

How long would it take?

Especially if PG&E fights back, a state takeover attempt could delay the company’s exit from bankruptcy — a potentially unwelcome prospect for wildfire victims and other groups.

PG&E’s proposed reorganization plan includes settlements to pay $25.5 billion to individuals, insurance companies, local governments and others with wildfire-related claims. The money is slated to be paid out when the utility emerges from bankruptcy, so a delay could mean wildfire victims have to wait additional months or years for compensation.

Wiener’s legislation is designed to take effect after the utility exits bankruptcy, meaning that at least under his plan, payments to wildfire victims would not be postponed.

Some clean energy advocates are also concerned about the possibility of an extended delay.

PG&E is one of the country’s largest buyers of solar and wind power, and it has been praised by environmental groups for its advocacy on energy efficiency. California will need to accelerate its transition to those types of clean resources if it hopes to reduce planet-warming emissions 40% below 1990 levels by 2030, as required by state law.

“For all their faults as a company, and they have many, PG&E actually has a pretty good track record when it comes to embracing climate change as a serious priority,” said Michael Colvin, who leads the California energy program at the nonprofit Environmental Defense Fund.

How much would customers pay?

Statewide, homes served by publicly owned utilities pay less for electricity than homes served by investor-owned utilities.

Data compiled by the American Public Power Assn. show that in 2018, California’s investor-owned utilities collected 19.3 cents in revenue, on average, for every kilowatt-hour of electricity they sold to residential customers. The revenue figure for publicly owned utilities was much lower: 16.4 cents.

Still, experts caution that the ability of a publicly owned PG&E to offer lower rates would depend in part on the price California pays to acquire the company’s assets, since ratepayers would be on the hook for those costs. A higher purchase price could cut into the cost savings from eliminating guaranteed returns on investment for shareholders.

Another complicating factor is the need to invest tens of billions of dollars in PG&E’s poles and wires in the coming years, to harden that aging infrastructure against starting fires.

Shon Hiatt, a professor of management at USC’s Marshall School of Business, said that if the state takes over PG&E, the utility would no longer be able to issue common stock to help pay for those infrastructure projects. That means the money would need to come from either taking on more debt or raising rates.

“The question is, how high will these rates go?” Hiatt asked.

Wildfire-prevention outages by PG&E and Southern California Edison have thrown the reliability of the power grid into doubt.

A more existential question is whether a publicly owned PG&E would be any more up to the task of stemming wildfires and keeping the lights on than the current version.

The company’s critics say the state could hardly do worse than PG&E has in recent years, arguing the stockholder-owned company has consistently put profits ahead of safety.

“They have no credit. Their cost of capital is horrendous. Their insurance is horrendous,” said Jeff Shields, a public power veteran who helped form Trinity Public Utilities District.

But revamping PG&E’s massive electric system — which includes more than 18,000 miles of transmission lines across a 70,000-square-mile service territory — won’t be an easy task no matter who is responsible for it. Some experts aren’t sure a government agency would do any better at the gargantuan undertaking than the current iteration of PG&E.

“The state taking it over doesn’t mean it’s going to run it more efficiently,” said John Coffee Jr., a professor at Columbia Law School.

Supporters of taking PG&E public say the obstacles are surmountable.

Public utilities, they say, are subject to the same clean energy mandates as their private counterparts. Laws can be written to protect workers. The elected officials running a reformed PG&E can choose to dedicate sufficient funds to safety, rather than paying dividends to shareholders and wining and dining regulators.

And a transfer to public ownership wouldn’t have to take as long as the Sacramento battle of the 1930s and 1940s, not with PG&E facing enormous political and financial pressures of its own making.

“I wouldn’t underestimate the power that this governor has to speed things along,” said Catie Stewart, a spokeswoman for Wiener.

Still, a government-run utility wouldn’t be immune from the kinds of problems that have plagued PG&E.

Paul Hauser, general manager of Trinity Public Utilities District, pointed out that California’s “strict liability” standard — under which utilities can be held responsible for fires ignited by their equipment, even if they weren’t negligent — applies to public and private entities alike. It’s a sword of Damocles hanging over anyone who owns a piece of the power grid.

What does that mean for public officials who might want to take over a private utility? Hauser pointed to the small part of Trinity County that is still served by PG&E.

“Under today’s strict liability standard, I don’t know if we’d want it,” he said. “I don’t know if we’d want it if it were given to us.”

Times staff writer Taryn Luna contributed to this report.