California needs clean energy after sundown. Is the answer under our feet?

After years of playing third fiddle to solar and wind power, geothermal energy is poised to start growing again in California.

Three local energy providers have signed contracts this month for electricity from new geothermal power plants, one in Imperial County near the Salton Sea and the other in Mono County along the Eastern Sierra. The new plants will be the first geothermal facilities built in California in nearly a decade — potentially marking a long-awaited turning point for a technology that could play a critical role in the state’s transition to cleaner energy sources.

Geothermal plants can generate emissions-free, renewable electricity around the clock, unlike solar panels or wind turbines. The technology has been used commercially for decades and involves tapping naturally heated underground reservoirs to create steam and turn turbines.

Despite those advantages, development has been bogged down by high costs. Building a geothermal facility can be several times more expensive than a comparably sized solar or wind farm, meaning geothermal plant operators must charge more for the electricity they generate.

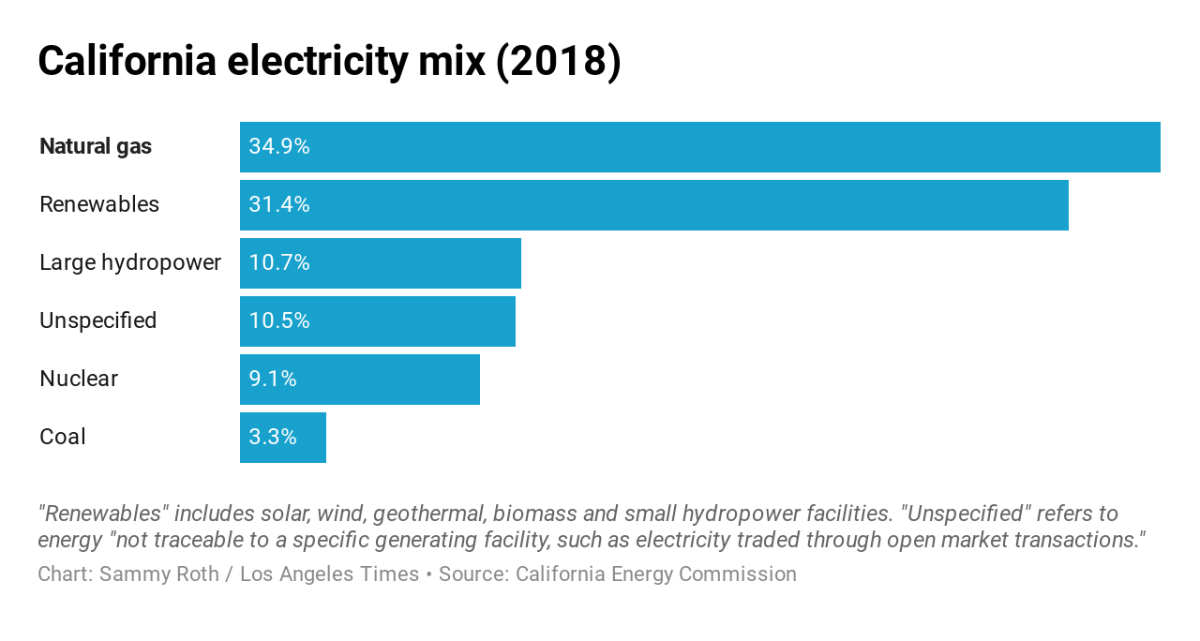

Geothermal accounted for 4.5% of California’s electricity mix in 2018 — about one-fifth the amount supplied by solar and wind, which made up the bulk of California’s renewable energy supply.

Now those dynamics may be starting to shift.

State lawmakers passed a bill in 2018 mandating 100% climate-friendly electricity by 2045. As energy providers forecast their supply needs in a not-too-distant future without fossil fuels, some have decided it makes sense to start adding geothermal to the mix.

“At the face of it, geothermal tends to be more expensive than other resources, especially solar. But you have to really look at the value proposition, not just the cost,” Monica Padilla, director of power resources for Silicon Valley Clean Energy, told the agency’s board of directors this month.

Silicon Valley Clean Energy teamed up with another local electricity provider, Monterey Bay Community Power, to negotiate a contract with Ormat Technologies of Reno for 14 megawatts of power from a geothermal plant the company plans to build in Mono County.

The rest of the facility’s capacity is already under contract to Colton, a city in San Bernardino County, under a deal signed last year. It’s due to come on line in 2021, nine years after the state’s last geothermal plant opened.

The second new plant is planned for Imperial County, near the southern shore of the Salton Sea, with commercial operation expected in 2023.

Controlled Thermal Resources, the Australian developer of the so-called Hell’s Kitchen geothermal project, also plans to extract lithium from the hot, salty underground fluid that will be used to make electricity. The company hopes to create a major new domestic source of the mineral, which is a key ingredient used in batteries for electric cars and energy storage.

The Imperial Irrigation District agreed to buy 40 megawatts of geothermal energy from Hell’s Kitchen over a 25-year contract the utility valued at $627 million. Power purchase contracts are typically necessary before large renewable energy projects can get built, because they make it possible for developers to secure financing for construction.

Controlled Thermal Resources is negotiating additional contracts for power and lithium sales to fill out the 140-megawatt project, Chief Executive Rod Colwell said.

After seven years working on Hell’s Kitchen, “we’re very excited about the next three years of actually delivering the project,” he said.

A geothermal power company says it can make California’s Salton Sea the first major source of U.S. lithium production.

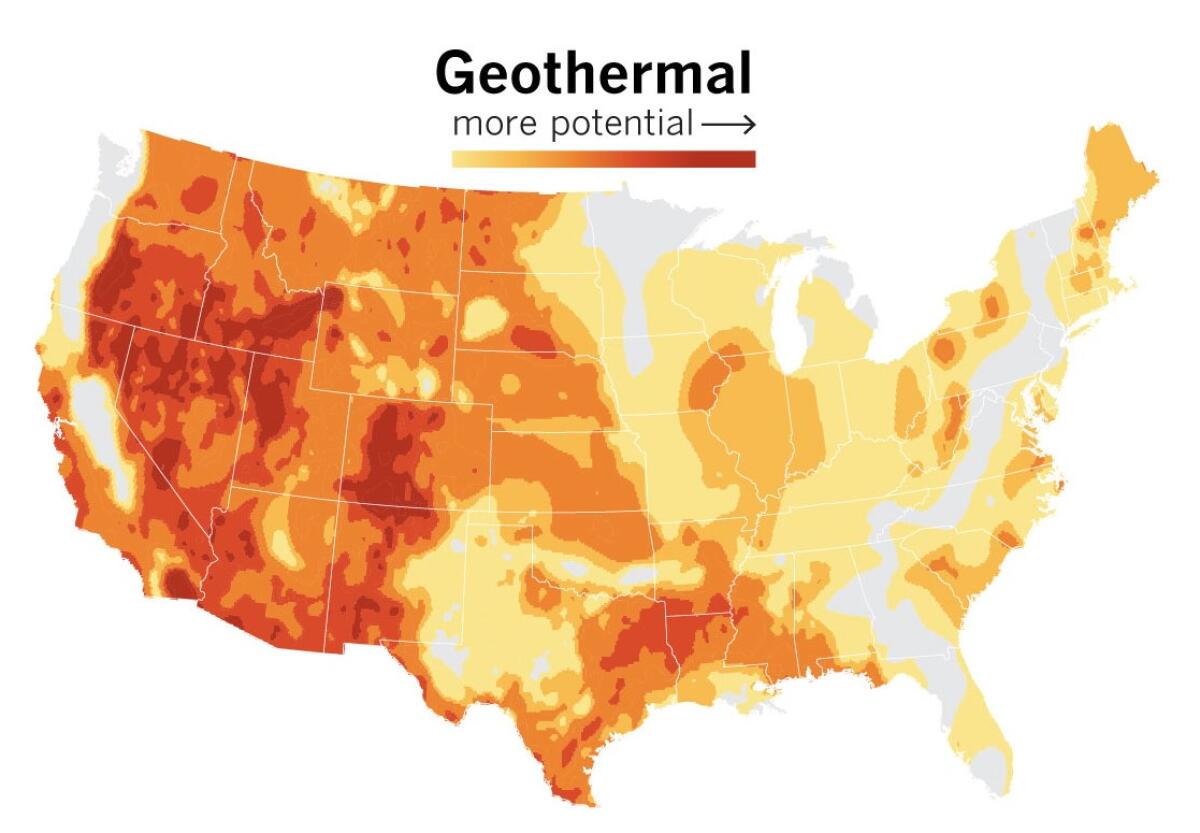

Geothermal plants have traditionally been limited to naturally occurring “hot spots” where drilling rigs can access high-temperature fluid relatively close to the Earth’s surface. Most U.S. geothermal resources are located in the West. Some of the strongest underground reservoirs are in California due to the state’s location along the seismological “Ring of Fire,” where the tectonic plates of the Pacific Ocean and North America collide.

The California Energy Commission lists 43 geothermal plants in the state, most of them clustered at the Geysers complex north of the Bay Area and in the Imperial Valley. Many of those facilities opened in the 1970s and 1980s and have been churning out climate-friendly electricity ever since.

State lawmakers have rejected proposals in recent years to require more geothermal power. But regulators tasked with charting California’s path to 100% clean energy are now contemplating a doubling of geothermal capacity on the state’s main power grid by 2030.

Some experts say more than a doubling is possible.

The U.S. Geological Survey estimated in 2008 that California has nearly 15,000 megawatts of geothermal potential — nearly one-fifth of the total capacity of all power plants in the state today. That number could rise substantially if energy companies are able to develop new technologies that allow them to exploit deeper, lower-temperature geothermal reservoirs that currently aren’t economically feasible.

The federal Department of Energy is supporting those technology efforts through an initiative called FORGE, or Frontier Observatory for Research in Geothermal Energy. Last year the department announced $140 million in research and development funding for the University of Utah, which operates a field laboratory to test new techniques.

The Department of Energy released a report last year finding that if technology improves, U.S. geothermal capacity could grow from 2,500 megawatts today to 60,000 megawatts by 2050 — or as much as 120,000 megawatts in a scenario in which high natural gas prices make geothermal more competitive. Under that scenario, geothermal power plants, mostly in the West, could generate 16% of the nation’s electricity.

That kind of expansion would require unprecedented innovation from an industry that has been stagnant for decades, with none of the significant cost declines or technological improvements that have spurred the growth of solar and wind power.

But geothermal advocates and entrepreneurs are hopeful.

Tim Latimer co-founded the Berkeley-based geothermal start-up Fervo Energy, which has received funding from sources including Breakthrough Energy Ventures, a fund led by Bill Gates. Fervo is working to develop horizontal drilling techniques with similarities to those used by the oil and gas industry, which could make it easier for energy companies to find and tap geothermal reservoirs.

“Most people recognize we need another resource in the mix to achieve full decarbonization,” Latimer said, referring to the process of eliminating planet-warming carbon dioxide emissions from fossil fuels.

Los Angeles hopes to store solar and wind power in underground salt caverns, to help replace a giant coal plant.

California’s climate change policies have created an “unparalleled market” for geothermal, said Paul Thomsen, vice president for business development at Ormat Technologies and a former chair of the Nevada Public Utilities Commission. California’s 100% clean energy mandate, along with the state’s goal of carbon neutrality by 2045, means natural gas will eventually need to be squeezed off the grid, Thomsen said — creating an opening for geothermal.

Meanwhile, other states in the geothermal-rich American West are beginning to follow California’s lead. Lawmakers in Nevada, New Mexico and Washington set 100% clean energy targets last year, as have western electric utilities Avista, Idaho Power and Xcel Energy.

“Every state that wants to see deep renewables penetration is going to need a resource that can be there 24 hours a day with no carbon. And that’s going to create a continued growing market for geothermal,” Thomsen said.

The rapid growth of intermittent solar and wind power is already forcing California utilities to rethink their operations, even with the state’s 100% clean energy target still 25 years away.

The solar farms that increasingly flood the the state’s power grid during the afternoon go off-line each day at sundown, when they’re typically replaced by natural gas plants. But gas plants are closing as a result of poor economics and anti-fossil-fuel activism, a trend that state regulators worry could lead to evening power shortages in the next few years if corrective action isn’t taken.

With a 2020 shutdown deadline looming, four coastal gas plants have become an early battleground in an increasingly urgent debate.

Geothermal is far from the only technology that might help replace natural gas.

New solar farms in California are being built with lithium-ion batteries, which can provide a few hours of electricity after sundown. Other technologies such as offshore wind turbines, renewable hydrogen and compressed air energy storage might also help fill the gap.

But for some energy providers, geothermal is looking increasingly attractive.

“This is something that we have to start doing now as the procurement requirements continue to increase and get more definitive,” Henry Martinez, general manager of the Imperial Irrigation District, told the agency’s board of directors this month. “The last thing I want to do is have the district end up with a situation where we have to make a drastic decision at the last minute.”

Imperial agreed to pay an average of 7.4 cents per kilowatt-hour of electricity from the Hell’s Kitchen geothermal plant. That’s more than twice as much as the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power recently agreed to pay for a record-cheap solar-plus-battery-storage project.

Still, it’s near the low end of the latest cost estimates for geothermal power from the investment bank Lazard.

Monterey Bay Community Power and Silicon Valley Clean Energy didn’t disclose how much they agreed to pay for the combined 14 megawatts of geothermal power they will buy from Ormat’s 30-megawatt Casa Diablo IV geothermal project in Mono County. The city of Colton, which is buying the rest of the project’s capacity, disclosed it will pay 6.8 cents per kilowatt-hour.

The new contracts are relatively small. But for an industry that hasn’t built any new projects in California since 2012, they’re a start.

“Who’s going to provide dependable electricity?” asked Ian Crawford, director of communications for the Davis-based Geothermal Resources Council. “I think geothermal stands a chance of being recognized at last.”