How Disney’s Sierra Nevada ski resort changed environmentalism forever

This is the Jan. 5, 2023, edition of Boiling Point, a weekly newsletter about climate change and the environment in California and the American West. Sign up here to get it in your inbox.

Let’s start 2023 by looking six decades into the past.

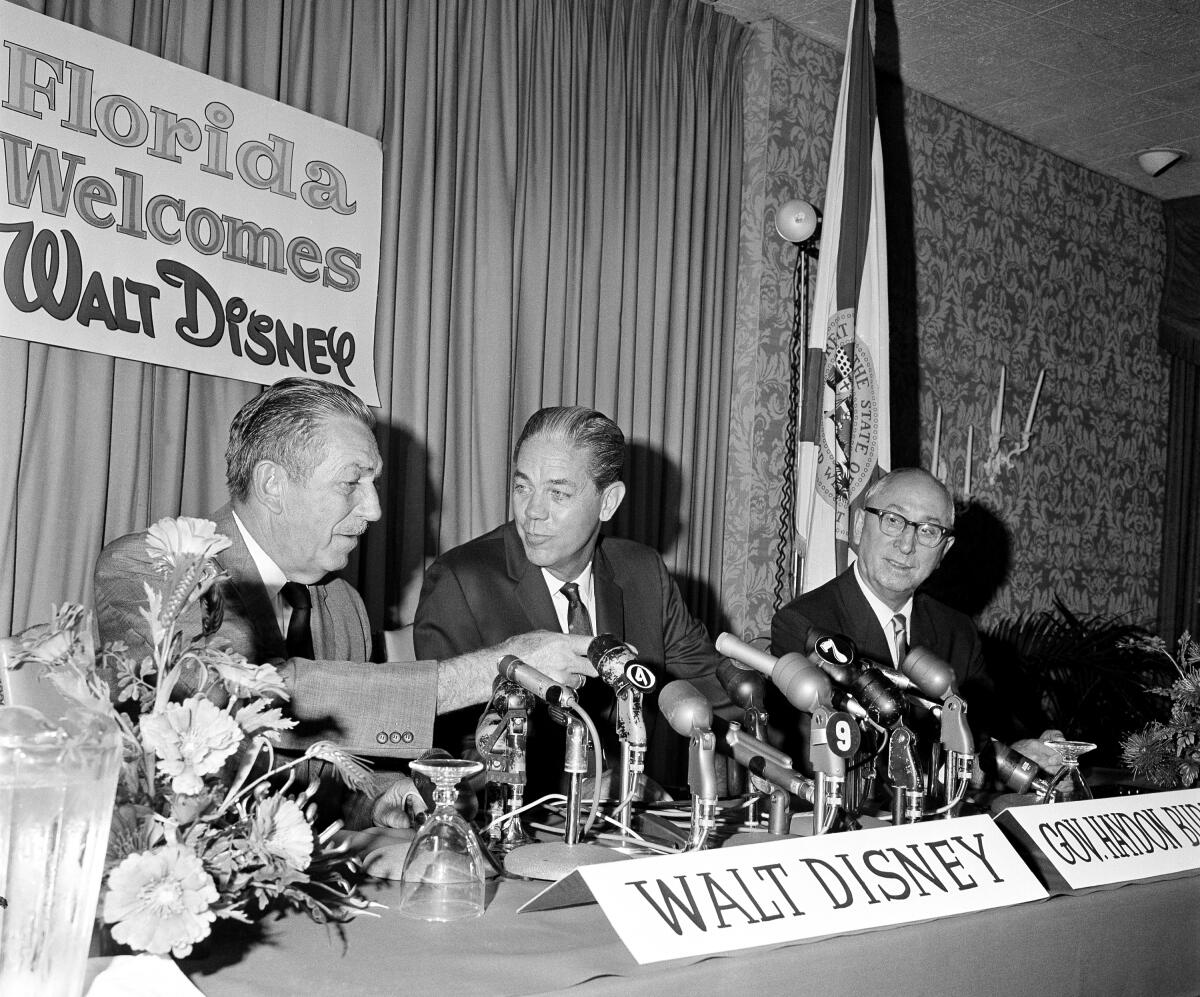

That’s how long it’s been since Walt Disney proposed building a massive ski resort at Mineral King, a gorgeous mountain valley in California’s Sierra Nevada bordered on three sides by Sequoia National Park. The ensuing controversy — and Sierra Club lawsuit against the U.S. Forest Service — played a significant role in shaping the modern environmental movement.

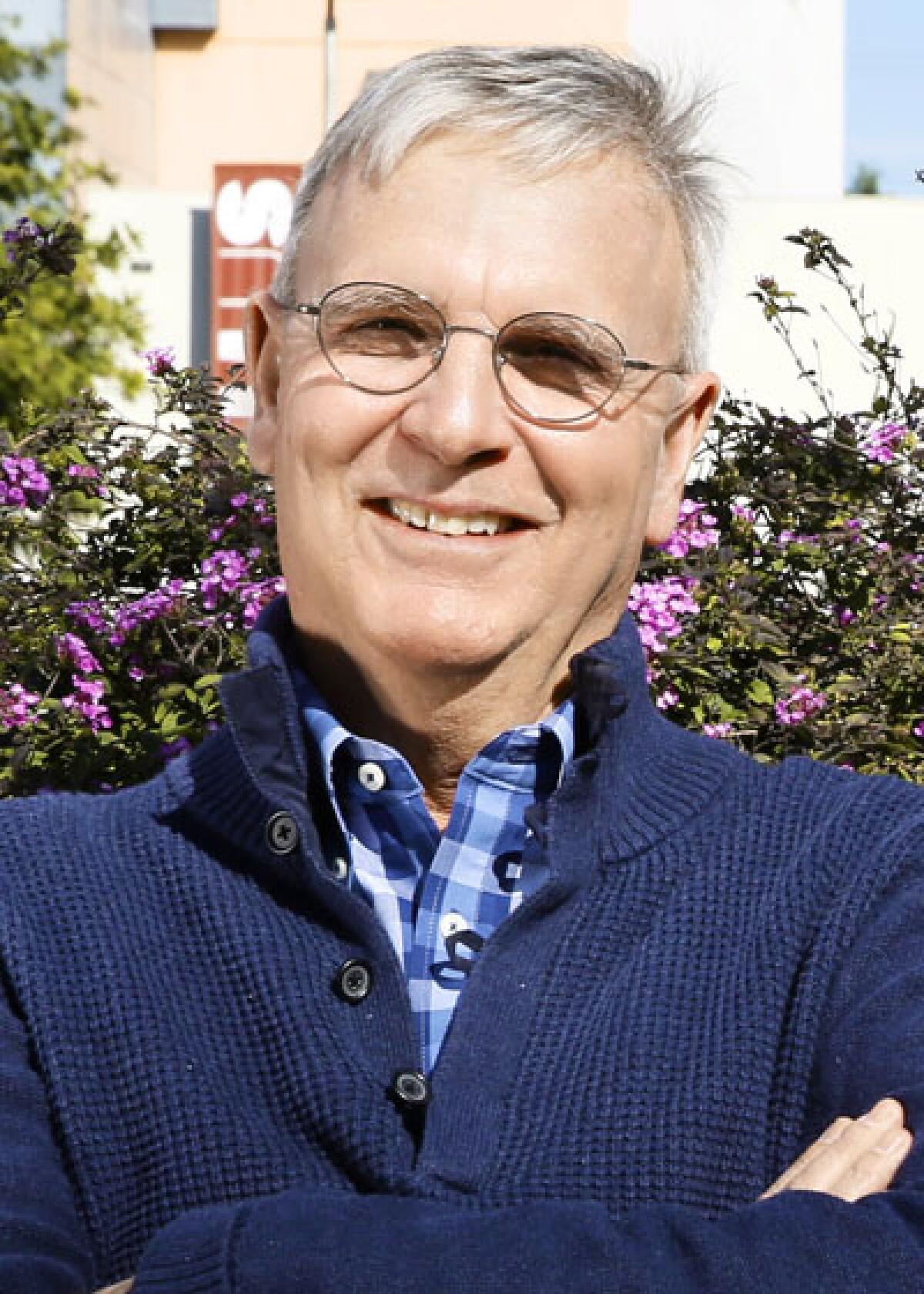

It’s a story that Daniel Selmi, an emeritus law professor at Loyola Law School in Los Angeles, deftly brings to life in a book released last year, “Dawn at Mineral King Valley: The Sierra Club, the Disney Company, and the Rise of Environmental Law.”

The Sierra Club technically lost its court battle. But the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1972 ruling helped establish the principle that environmental groups can sue government agencies, clearing the path for much of the climate-focused litigation we see today.

The lawsuit also contributed to Walt Disney Co. scrapping its ski resort and Congress adding Mineral King to Sequoia National Park. The Sierra Club, meanwhile, found itself transformed from a relatively nonconfrontational band of outdoors enthusiasts to the harder-core, more organized conservation activists known today for their legal and lobbying muscle.

As a mountain hiker and Disney fan intrigued by the intersection of entertainment and the climate crisis, I was fascinated by the important questions Selmi’s book raises about how to preserve our increasingly crowded public lands, and the role of government agencies and corporations in environmental protection.

I got in touch with Selmi to chat about those topics. He told me he first visited Mineral King in the 1970s, when he was a law student and the Supreme Court’s decision was fresh. He described the valley as “spectacularly beautiful.”

The following transcript of our conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

**

In Sierra Club vs. Morton, the Supreme Court settled the question of “standing” in environmental cases — meaning, what environmental groups must prove before they can sue the government. Talk about why that matters today.

It’s relevant in almost all environmental litigation. Standing is a requirement that you must meet to bring any case. But in the environment area it was a new issue, because up until the late 1960s nobody brought environmental cases. So the idea of what you had to prove by way of injury was a new question.

In the Mineral King case, the Supreme Court said that you have to prove “injury in fact,” and that somehow your injury is being caused by the decision the government is making. So for example, in cases involving water pollution, you have to show that you use the river, and the pollution restrains you from using it. That idea has proven widespread in environmental litigation. And it’s turned out that most environmental plaintiffs don’t have a whole lot of trouble proving it.

You explain in the book that Forest Service officials were aghast at the idea of conservationists challenging their decisions in court. The Forest Service argued that opening the courts to environmental groups would result in government agencies being inundated with lawsuits and major decisions getting dragged out for years. That’s pretty much the reality we live in today. Do you think the Forest Service was right to be concerned?

There are certainly positive and negative effects. On the one hand, lawsuits do delay things. No question about that.

On the other hand — just to take one example — the Forest Service said repeatedly they had studied Mineral King to death before deciding to put a ski area there. And they hadn’t done that. Public agencies now have to justify what they’ve done in much greater depth than they did before. It’s like night and day. They have to be concerned with the law.

I think the overall effect has been beneficial. It’s important for public agencies to have to justify their decisions, ground those decisions in evidence and give the public the ability to comment. And if there’s other evidence the agency is ignoring, the public can put that in front of them, and they have to deal with it.

More recently, environmentalists have filed lawsuit after lawsuit against federal agencies on climate change grounds. They’ve had a decent amount of success getting judges to block or delay fossil fuel lease sales on public lands and waters. Those suits aren’t possible without the Mineral King precedent, right?

That’s exactly right.

Before Mineral King, the Sierra Club and most other prominent environmental groups weren’t especially litigious. Was this case the moment in time when that started to change?

Absolutely. It started as a trickle before Mineral King. Environmental groups got a couple of lower-court decisions that held they had standing to sue, and then in the Mineral King case, the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals said there wasn’t any standing. So that put the whole thing up in the air again, until the Supreme Court settled the matter.

Environmental groups saw litigation as a new means of holding government agencies accountable. The Sierra Club Legal Defense Fund — known today as Earthjustice — was started. The Natural Resources Defense Council, the Center for Biological Diversity — all those groups have legal staffs now. And that’s a direct result of their being able to litigate.

So much of your book is about tension between conservation and recreation on public lands, which is still a serious conflict. Especially since the start of the pandemic, more people than ever are hiking, camping and otherwise enjoying national parks and monuments. At times, that’s led to overcrowding, and damage to wildlife habitat.

Meanwhile, the Biden administration has endorsed the conservation movement’s “30 by 30” goal of protecting 30% of U.S. lands and waters by 2030. With those competing forces in mind, what lessons can we draw from Mineral King?

Well, Mineral King is a little distinct. The Mineral King Valley was surrounded on three sides by Sequoia National Park. The only reason it wasn’t in the park was because there were old mining claims. There’s a good argument that for that reason alone, it belonged in the park, because it should have been there to begin with.

One overriding lesson, though, is not to move too quickly when you make long-term decisions about public lands with obvious recreation or wilderness values. The Forest Service’s Mineral King decision was run through relatively quickly at first. If the Sierra Club hadn’t sued, the ski resort would have been built. And that was a major decision for an unbelievably beautiful area.

You quote a 1978 letter from Card Walker, Disney’s chief executive at the time, to President Carter. Walker blames “a very small but highly organized and influential minority of preservationists” for blocking its project. There are plenty of similar debates today. They come down to whom America’s public lands are for, and who gets to make those decisions.

I think that’s right. Ultimately, Congress made the decision to protect Mineral King, which for something this important is the most appropriate body to make that choice. It’s certainly not going to be the case for all public lands decisions, though.

There has to be a lot of concern over irreparable harms. Are we doing something that in the long run is going to foreclose other land uses, or destroy the area in question?

I was also intrigued to learn about Disney’s proposal to build an electric railway to Mineral King, after an earlier plan to expand a road through Sequoia National Park ran into opposition. That part of the story feels relevant today, too, when there’s so much focus on getting cars out of national parks to limit traffic jams and pollution.

You really have to start with Stewart Udall, who was secretary of the Interior and ahead of his time. He was an environmentalist, and he had this strong feeling that we were over-relying on the automobile. He was trying to force another solution on Mineral King, which was some sort of railroad. Disney was dead against it at first. They really fought it.

It’s to Disney’s credit that they eventually changed their minds, even if it was self-serving. It just turned out to be too late.

Do you think Disney could have built a smaller ski resort and sufficiently preserved Mineral King? Or was this a situation where the only environmentally sound solution was to block all development?

I think you have to define what you mean by “preserve Mineral King.” To me, the factor that’s still of overriding importance is that the national park was all around it. This is a different story if it’s not surrounded by Sequoia National Park.

But even without the park, Disney’s ski resort would have had to be smaller. At some point, you end up with a project so big that you lose sight of the area itself. You have to make a decision — is this an area of such breathtaking beauty that 100 years from now we want people to be able to go in there and look at it and say, “Wow,” without seeing skiers?

That’s the ultimate decision. And that kind of balance is very difficult to decide.

Is balance still the right idea with the conflicts we face on public lands today? There’s more and more research showing that even small disturbances to wildlife habitat can have destructive environmental ripple effects. And when it comes to oil and gas leasing, there are many climate activists who say we should shut off the spigot entirely.

We have an enormous amount of scientific evidence about ecosystems that we didn’t have 50 years ago. We understand better now how interfering with one part of the ecosystem can affect another part of the ecosystem. So when do you allow that? Well, presumably when there’s some sort of competing value that you think makes it worthwhile.

One of the fascinating things about Mineral King was that the valley was a congressionally designated game refuge. And the Forest Service’s position was you could put a huge ski area in there, and it was still going to be a game refuge.

Legally, that may have been right. But it’s another example of what went wrong here. The Forest Service never studied what the impact was going to be on the game refuge. They weren’t worried about it.

Watch L.A. Times Today at 7 p.m. on Spectrum News 1 on Channel 1 or live stream on the Spectrum News App. Palos Verdes Peninsula and Orange County viewers can watch on Cox Systems on channel 99.

**

New year, same Boiling Point. Here’s what’s happening around the West:

TOP STORIES

California has shifted abruptly from not enough water to far too much, with a powerful storm bringing floods, power outages, landslides and at least two deaths. My colleagues Michael Finnegan and Jessica Garrison chronicled the mayhem, which included San Francisco’s second-wettest day in more than 170 years and deadly flash flooding along Highway 99 near Sacramento. As of Tuesday, snowpack in the Sierra Nevada was 174% of average, Ian James reports, at least giving us hope that 2023 won’t be as parched as 2022. But with another atmospheric river set to hit Wednesday and Thursday, the wet weather also offers a harsh reminder that climate change is leading to increasingly intense swings between drought and flood. Hayley Smith wrote about why that drought-flood whiplash is so dangerous. And Jessica Roy explained how to prepare and stay safe.

Scientists don’t know why California’s winter-run Chinook salmon have been feasting so heavily on anchovies. But this new dietary habit is killing the endangered fish, The Times’ Susanne Rust and Ian James report. Anchovies may be delicious, but they carry an enzyme that breaks down thiamine, a vitamin essential to cell function. And it’s not just thiamine deficiency killing young salmon — drought, extreme heat and debris flows from wildfire burn scars are problems too. The number of juvenile winter-run Chinook that were counted swimming downstream past Red Bluff Diversion Dam in 2022 was the lowest on record.

The Black family that took back ownership of Bruce’s Beach last year — nearly a century after local officials stole the prime piece of coastal real estate — has decided to sell the land back to Los Angeles County for nearly $20 million. Here’s the story from my colleague Rebecca Ellis, who notes that L.A. County’s agreement to return the property to the Bruce family included a two-year window in which they could choose to sell it back. “My clients were essentially robbed of their birthright,” an attorney for the family said. “They should have grown up part of a hospitality dynasty rivaling the Marriotts and the Hiltons.”

AROUND THE WEST

Conservationists in the Eastern Sierra have asked California officials to order Los Angeles to stop taking water from Mono Lake, to protect one of the world’s largest populations of nesting gulls. If the state doesn’t cut off L.A.’s water diversions, the nonprofit Mono Lake Committee argues, coyotes will be able to cross the exposed lake bottom and reach once-protected islands, where they’ll feast on the eggs of 50,000 California gulls, my colleague Louis Sahagún writes. It’s worth nothing that Mono Lake is just one of many declining salt lakes in the American West, including Utah’s Great Salt Lake. President Biden signed a bill last week setting aside $25 million to study those bodies of water, including Mono Lake, the Associated Press’ Sam Metz reports.

Western firefighters say Hollywood storytellers are getting wildfire wrong — or at least they’re behind the times. For a story focused on the CBS drama series “Fire Country,” NPR’s Chloe Veltman talked with firefighters who want to see TV shows and movies that feature more discussion of climate, more focus on preventive measures such as prescribed burns and less clichéd melodrama. It’s all part of the need for more and better portrayals of climate change on our screens, a topic I wrote about last year. In another fire story, High Country News’ B. ‘Toastie’ Oaster wrote about a Karuk Tribe training program for Indigenous women to run prescribed burns. It’s an effort designed, in part, to eliminate hyper-masculinity in firefighting culture.

A year after the destructive Marshall fire, Colorado is still one of eight states without a minimum construction standard for homes. People are rebuilding with the same flammable materials, as the construction industry and some local governments continue to fight new requirements for fire-safe homes, citing high costs — even though the costs of destruction when fire does come are much higher, as Jennifer Oldham reports for ProPublica and Colorado News Collaborative. In Oregon, meanwhile, rural residents have protested a new wildfire risk map that could ultimately force them to create defensible space on their properties, prompting state officials to rework the map, High Country News’ Kylie Mohr writes. “It’s sort of a condensed version of the climate change test,” one state lawmaker said. “Which is: Do we have the capacity to respond and save ourselves, or not?”

THE ENERGY TRANSITION

Wyoming residents will pay an estimated $2 million this year to fund studies analyzing the possibility of carbon capture at coal plants, as mandated by state law. Details here from Dustin Bleizeffer at WyoFile, who writes that lawmakers’ determination to save the coal industry — despite growing evidence that carbon capture at coal plants is wildly expensive, and the availability of cheaper, cleaner energy sources — will result in electricity rate hikes for Rocky Mountain Power customers in 2023.

Speaking of coal, an underground coal mine fire has been burning for more than three months in Utah, threatening to shutter the mine and put hundreds of people out of work if the fire can’t be extinguished. The mine supplies two coal-fired power plants in a state that still gets 61% of its electricity from the dirtiest fossil fuel, Sara Ruberg reports for NBC News. This kind of thing is surprisingly common, with one expert saying some coal fires have been burning for more than 1,000 years.

Just one bid was submitted in the federal government’s first oil and gas lease auction off the coast of Alaska in five-plus years. Not exactly a ringing endorsement for offshore drilling. Reuters’ Nichola Groom and Valerie Volcovici have the story.

POLITICAL CLIMATE

The Biden administration has revamped a Trump-era regulation spelling out which wetlands and other waterways are governed by the Clean Water Act, with major implications in Western states. The new “waters of the United States” rule is, unsurprisingly, supported by environmentalists and public health advocates and opposed by home builders and Republican politicians. But it may not matter: The Supreme Court’s 6-3 conservative majority could still toss the new rule in response to a lawsuit brought by an Idaho couple against the federal government, the Associated Press’ Jim Salter and Michael Phillis report.

America’s most prominent climate denier is no longer a member of the U.S. Senate. Longtime Oklahoma politician Jim Inhofe officially retired this week, nearly eight years after he brought a snowball to the Senate floor and attempted to use it as proof that global warming is not real. HuffPost’s Chris D’Angelo looked back at Inhofe’s history of ludicrous claims. And E&E News’ Timothy Cama counted dozens of former Inhofe staffers who now hold influential jobs connected to energy or the environment.

As California stops burning fossil fuels, not as many oil and gas industry employees will find themselves out of work as previously projected — and it won’t cost the state as much to provide income subsidies to those forced to switch to lower-paying jobs, either. That’s according to a new analysis by the Gender Equity Policy Institute, as reported by the Sacramento Bee’s Maggie Angst. Oil industry officials say the think tank’s analysis badly understates the extent of the problem.

ONE MORE THING

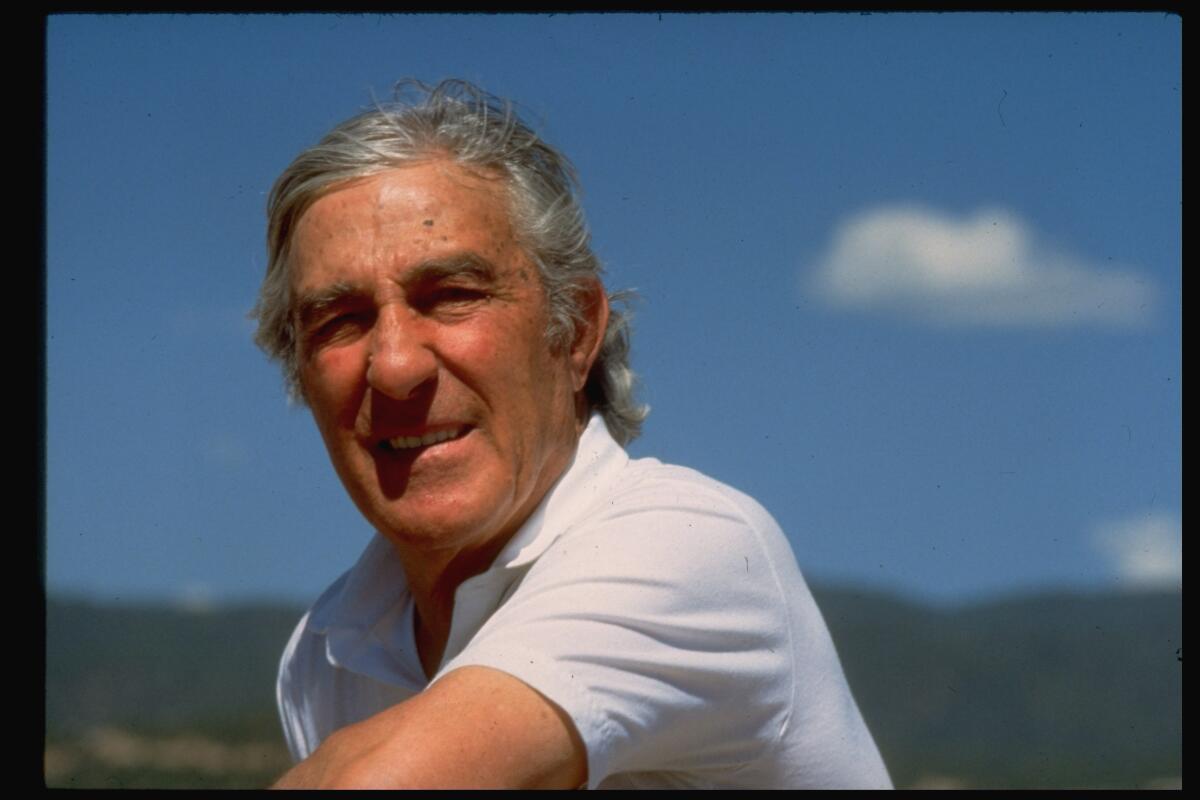

One of the key players in the battle over Disney’s proposed ski resort at Mineral King — the subject of the above Q&A — was Stewart Udall, who served as Interior secretary in the 1960s. He opposed efforts to provide access to the ski resort by expanding a road through Sequoia National Park, arguing that increased car traffic would mar the park with “fumes, noises, and accompanying clutter.”

Daniel Selmi’s book quotes a 1967 essay that Udall wrote for the L.A. Times, “The Face of Tomorrow,” in which the Interior secretary discusses the importance of preserving intact landscapes and healthy ecosystems in the West — and the role of technology in that pursuit. Although some of Udall’s ideas — such as cleaner coal plants and extensive tunneling beneath cities — feel kooky or misguided in retrospect, his overall themes of respecting the natural world and limiting reliance on the automobile continue to resonate.

“We are an internal combustion-oriented society now choking miserably on the wastes of the horsepower chambers,” he wrote.

It’s still true today. And with the climate crisis worsening, solutions are more necessary than ever.

We’ll be back in your inbox next week. If you enjoyed this newsletter, or previous editions, please consider forwarding it to your friends and colleagues. For more climate and environment news, follow me on Twitter @Sammy_Roth.

Toward a more sustainable California

Get Boiling Point, our newsletter exploring climate change, energy and the environment, and become part of the conversation — and the solution.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.