Appreciation: Bob Elliott’s gone, but his influence on modern comedy remains

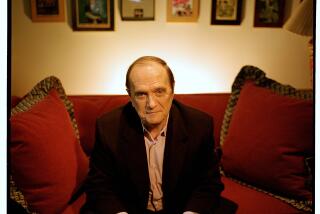

Bob Elliott, the half of the comedy duo Bob & Ray who was named Bob, died Tuesday at home in Maine, at the age of 92. I am trying hard not to take this personally.

The father of the comedian and actor Chris Elliott – in life and on Elliott’s sitcom “Get a Life” – and the grandfather of the comedians and actors Abby Elliott and Bridey Lee Elliott, he was most famously the partner of Ray Goulding, with whom he worked, mostly and most significantly on radio, from the 1940s into the 1980s. (Goulding died in 1990.)

Like radio comedy itself, they began as a kind of rumor to me; my father used to like to repeat their sign-off line, “Write if you get work…. and hang by your thumbs.” Wally Ballou, the roving reporter played by Elliott, whose broadcasts always began halfway into his first name (“--ly Ballou here”), was a name I knew long before I ever heard that character, “winner of over seven international diction awards,” speak.

SIGN UP for the free Classic Hollywood newsletter >>

In fact, they were still on the radio, just not in my neighborhood, continuing to do their deadpan double act into the 1970s over WOR in New York; in some respects, their radio work prefigured the loose comedy of modern drive-time radio, though it remains brighter, quicker, faster, funnier, tighter, cleverer and stranger. And then they were suddenly visible – not revived, exactly, but more widely present.

They were on Broadway, and at Carnegie Hall, and there were records, and talk show appearances. And then they were back on the radio, nationally, with an NPR series, “The Bob and Ray Public Radio Show,” that added great new segments, like the prime-time soap parody “Garish Summit,” to their repertoire.

And dozens upon dozens of hours of their pre-NPR radio work were eventually issued on cassette, then CD, then MP3. (BobandRay.com offers 90 hours on one convenient flash drive.) It has long been a habit in our household to finish the day listening to them; many, even most nights, Bob’s is the last voice I hear before falling to sleep, unless it’s Ray’s.

Of course, this practice can also make it hard to fall asleep: I will never not laugh at Bob as an old gunfighter who’s describing the length of time it takes for him to draw and shoot, or the ridiculous French Canadian accent he sometimes used in episodes of “Tippy, the Wonder Dog.”

Elliott’s voice was the quieter of the two – Ray was the bigger character, in body as well. It was a New England voice, out of Massachusetts, with a Yankee propriety that underscored the seriousness of his straighter characters and ironically amplified the oddness of the others. Indeed, the surreal nature of Bob & Ray comedy was rooted in an easy naturalism that made it seem like they were talking off the top of their heads even when working off of a script. (There was plenty of ad-libbing, besides.)

You hear that tone in much modern comedy – Will Ferrell is certainly one of their cultural children, and Chris Elliott’s comic creations are in many respects just a more demented version of his father’s – which makes the originals seem all the more timeless.

Indeed, watching them re-create an old spelling-bee bit in the 1979 NBC special “Bob and Ray, Jane, Laraine and Gilda,” which teamed them with three stars of “Saturday Night Live,” one finds the younger comics all seem to be “doing comedy,” while the older ones are merely being their not quite accountable, deadpan selves.

There is little in the way of jokes in their comedy; it is all in the concepts – an interview with the president of a slow talkers association, a Bob & Ray “trophy train,” filled with mementos of their brilliant career, making its way across the country – and in the relationships, the inability of one character to get the point of another, or the disinclination to listen. Sometimes Bob was the straight man, sometimes Ray; and sometimes the straight man was actually the stooge. It was a fluid arrangement.

Of all the many series their series contained, none is more brilliant than “Mary Backstayge, Noble Wife,” which began as a parody of the radio soap “Mary Noble, Backstage Wife” – much of their comedy took off from radio and then television shows and advertisements – and morphed into a bizarre ensemble piece, in which a large stock company embarks on a series of adventures, traveling to Africa to film a TV special, getting captured by pirates, singing opera at La Scala, opening a restaurant whose menu consists entirely of toast. The manner in which the pair slips in and out of multiple voices, as complex and casual as a Harlem Globetrotters routine, is as great an aesthetic pleasure as I know.

As the surviving member, Bob’s continuing presence on Earth – and on television, film and radio, where he joined Garrison Keillor’s New York-based “American Radio Company of the Air” – was a balm to the faithful. And though, especially in the hours since his passing, one doesn’t have to look far into the old, new or social media to find fellow addicts, fanship still feels like a shared secret, an exclusive club, a special society.

When I meet a Bob & Ray fan, it’s like encountering an unexpected brother or sister; it’s a basis for bonding, the beginning of a beautiful friendship.

Twitter: @LATimesTVLloyd

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.