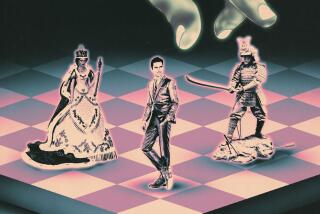

How shows like ‘Mad Men,’ ‘Vikings’ deal with less progressive pasts

When Ato Essandoh was offered the role of an African American doctor in Civil War-era New York City for BBC America’s “Copper,” he almost did a double-take. “My first thing was I had to look it up,” he says. “Lots of people didn’t really think there could have been an African American doctor in existence back then.”

There were a handful, and Essandoh was reassured that his Dr. Freeman character was based in reality and not some kind of magical modern thinking imposed on a less-culturally sensitive past. But he’s not alone in wondering if some characters in historically based TV series are too good to be true. Based on many current series, inhabitants of previous decades and centuries were seriously more progressive than previously understood.

Almost to a woman, female characters fight for equality (“Downton Abbey”) and prenatal care (“Boardwalk Empire”), men labor happily alongside female warriors (“Vikings”) and bosses (“Mad Men”) and good guys are always civil if not friendly to minorities: Dr. Freeman’s pal is a white police detective, and “Spartacus’” writers turned a real-life southern Italian, Oenomaus, into a black man.

TIMELINE: Emmy winners through the years

“Dealing with historical drama can be problematic,” acknowledges “Spartacus” show runner Steven S. DeKnight, whose show takes place circa 71 BC. “There are some things we can’t do — we couldn’t cast Asian actors; they didn’t know about Asia at this time. And there were things we had to ignore — women are not supposed to be in a public place without an escort, and we had to deviate from that for story reasons.”

It’s a fine line to walk between being historically respectful and creating a series that modern audiences can identify with. Dramas that turn every female character liberated or every minority into a fully integrated member of the business and social community risk seeming like they were written by a staff of Pollyannas.

“That is what happens in some dramas, where they get nervous about giving characters responses that are fitting of the era,” says “Downton” creator Julian Fellowes. “If you patronize the audience, they sense it.”

And while “Downton” may have a slightly greater population of budding feminists than might have existed in real rural, upper-crust England at the time, it did take a risk last season when butler Carson gave voice to his real feelings about homosexuality. “Ninety-nine percent of our audience I’m sure are highly tolerant, but 80, 90 years ago Carson is disgusted,” says executive producer Gareth Neame.

“The mistake is in thinking the audience won’t be interested in someone who is not extraordinary or a groundbreaker,” says “Mad Men” creator Matthew Weiner, whose women cover the spectrum of traditional to progressive. He says he walks carefully with his characterization of leading man Don Draper as decent-minded, but with culturally appropriate attitudes.

WATCH: The Envelope Emmy Round Table | Drama

“Don Draper is not a racist, but Don Draper is a bigot,” says Weiner. “Does Don want an African American to be on an account in their office? No.”

He notes that there would have been plenty of ahead-of-their-times individuals in Draper’s 1960s Manhattan, but it wouldn’t make sense to either feature his characters all as such progressives or interacting with them.

“Whenever we talk about the show, people start talking about [pioneering ad executive] Mary Wells,” Weiner says. “But when the show started, she was a secretary and we can’t even know what a big deal she was going to become. You can’t act like everybody was like that.”

Still, it’s hard to avoid searching the footnotes of history to find a justification for a character; in 2011, “Boardwalk Empire” brought on board a character based on a real-life female U.S. assistant attorney general. Says show creator Terence Winter, “It was great for us to portray a strong, powerful woman in an age and genre where you don’t get to do that very often.”

He adds, “I definitely don’t want to paint a false history to make people feel good.”

Instead, what most shows are aiming for is a sense of frisson between character and audience — and a sense of identification. “If you want to do a period story, you want to reflect the times we live in now and the issues and conflicts and struggles that happen to women or black and white and Latino regardless of the time they live in,” says “Copper” co-creator Tom Fontana, who says he echoes the intensity of New York post-9/11 in his Civil War-era New York chaos. “You want people to tune in and go, ‘Oh, that’s not so far away from what I’m going through.’”

And, from time to time, history itself actually favors the progressive future, as “Vikings” creator Michael Hirst discovered while researching the Nordic conquerors. Women fought alongside their men and held important positions in society outside of the home.

“I felt I could reach across to contemporary women and tell them something they didn’t know in a show that in theory is all about men in helmets,” he says. “I’m really happy to write about that and confound all the prejudices people have in the modern world.”

More to Read

From the Oscars to the Emmys.

Get the Envelope newsletter for exclusive awards season coverage, behind-the-scenes stories from the Envelope podcast and columnist Glenn Whipp’s must-read analysis.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.