Review: Ricky Gervais gets spiny and squishy in the Netflix comedy ‘After Life’

Ricky Gervais, who with Stephen Merchant created “The Office” and “Extras” early in this century, is starring in a new Netflix series, “After Life,” which he wrote and directed. It’s the story of a man who abandons civility after the death of his wife. It’s not wholly successful — a shade too obvious in some ways, too muddled in others, with one plot point I still don’t know how to deal with — but there are some fine performances and affecting moments. Its pleasures outweigh its problems.

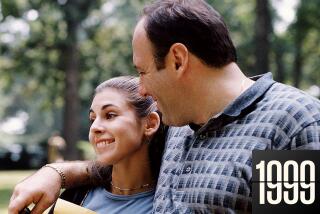

Gervais plays Tony, who works on a free newspaper in a small town, run by his exasperated but indulgent brother-in-law Matt (Tom Basden). His beat is human interest, and it doesn’t help that, angry and depressed over the loss of his wife, he has come to regard humanity as “a plague.” Reluctantly present at work, Tony is a mess at home, pouring cold cereal into a glass because all the bowls are dirty and eating it with water because he’s forgotten to buy milk. All that makes him happy is watching videos of beloved Lisa (Kerry Godliman), the ones he made of her and the one she left for him, “a little guide to life without me,” and walking his dog.

Tony’s stated decision to just do or say whatever he feels because nothing matters any more — it seems tangentially related to Gervais’ 2009 film “The Invention of Lying,” about a world in which everyone tells the truth — is not fully worked out. It feels almost beside the point. The creator’s comic sensibility can seem dismissive, but (with some unconvincing exceptions) it isn’t really dark.

Tony has a spiny shell but a squishy center — which might be said of Gervais’ work as a whole — and the show is a series of transgressions and apologies. Tony will threaten a 10-year-old with a hammer in one scene and in the next scene confess, amazed, that he threatened a 10-year-old with a hammer. (“They’ve got to learn,” says his father — played by David Bradley — from out of the mists of his dementia.)

Gervais is a decent but not deep actor; we accept his despair, as we accept his goodness, mostly because we are so often told about it, not because he makes us feel it.

“You know how grumpy you get when things don’t go your way,” his wife says with the narrative authority of the dying, “but you’ve got such a good heart. You’re born like it, you can’t contrive it, you’re just decent.”

But she is not the only one to endorse his character.

Though, as usual, he dominates the screen — every other person is meaningful only in their relation to him — Gervais is better at writing the characters he doesn’t play and directing the actors who play them. They hold the series aloft and give it layers, and may be divided into the silly and the serious. Among the former are advertising manager Kath (Diane Morgan), with whom Tony debates God, and photographer Lenny (Tony Way), whom he compares to Shrek and Jabba the Hutt. Among the latter: Anne (Penelope Wilton), a font of quiet wisdom he encounters regularly in the cemetery; Sandy (Mandeep Dhillon), the paper’s wide-eyed new hire; and Ashley Jensen, who was the soul of “Extras” and provides similar warmth here as the nurse taking care of Tony’s father.

Beyond them are the likable town junkie (Tim Plester), who also delivers, or fails to deliver, the newspaper; the friendly town “sex worker” (Roisin Conaty), and the nosy town postman (Joe Wilkinson). There are the curiosities upon whom Tony and photographer Lenny report upon — a man who received the same birthday card from five people, a couple whose baby looks like Hitler (but only because they have painted a mustache on him and combed his hair forward), a woman who sells rice pudding made with her own breast milk.

Tony mocks the mockable among them, but his principal beef is with irritating strangers — people who chew too loud, the charity worker who tries to shame him into giving, the teenagers who try to mug him, the waitress who won’t let him order off the children’s menu, easy targets Gervais the Writer has helpfully supplied his protagonist.

“You can’t just go around being rude to people,” says Matt.

“You can though,” Tony replies. “That’s the beauty of it. There’s no advantage to being nice and thoughtful and caring and having integrity. It’s a disadvantage, if anything.”

And yet, although we are supposed to enjoy his rudeness, and perhaps even to agree with him, we are also meant to judge his judging — to laugh with him and at him simultaneously. And to pity him too — his targets are happier than he is. Whether this is dramatically complicated or just messy I haven’t quite decided, but it’s notable, perhaps, that “The Office,” where this all started, was a show in which we watched a man watch himself being watched by a camera, revealing himself, and his flaws, in the course of putting on a character.

Like its snarky hero, “After Life” is essentially good-hearted. Many lines have the quality of being embroidered on a sampler — “Hope Is Everything,” “You Can’t Change the World But You Can Change Yourself,” “Nothing’s as Good If You Don’t Share It,” “We’re Not Just Here for Us, We’re Here for Others.” There is a sentimental montage near the end set to the California bathwater harmonies of the Thorns, and a scene in which Tony tells his heretofore abused co-workers why they’re special, like Dorothy bidding adieu to her companions at the end of “The Wizard of Oz.” These gambits are no less effective for their being so obvious.

‘After Life’

Where: Netflix

When: Any time, starting Friday

Rating: TV-MA (may be unsuitable for children under the age of 17)

Follow Robert Lloyd on Twitter @LATimesTVLloyd

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.