From the Archives: Nirvana’s Kurt Cobain was a reluctant hero who spoke to his generation

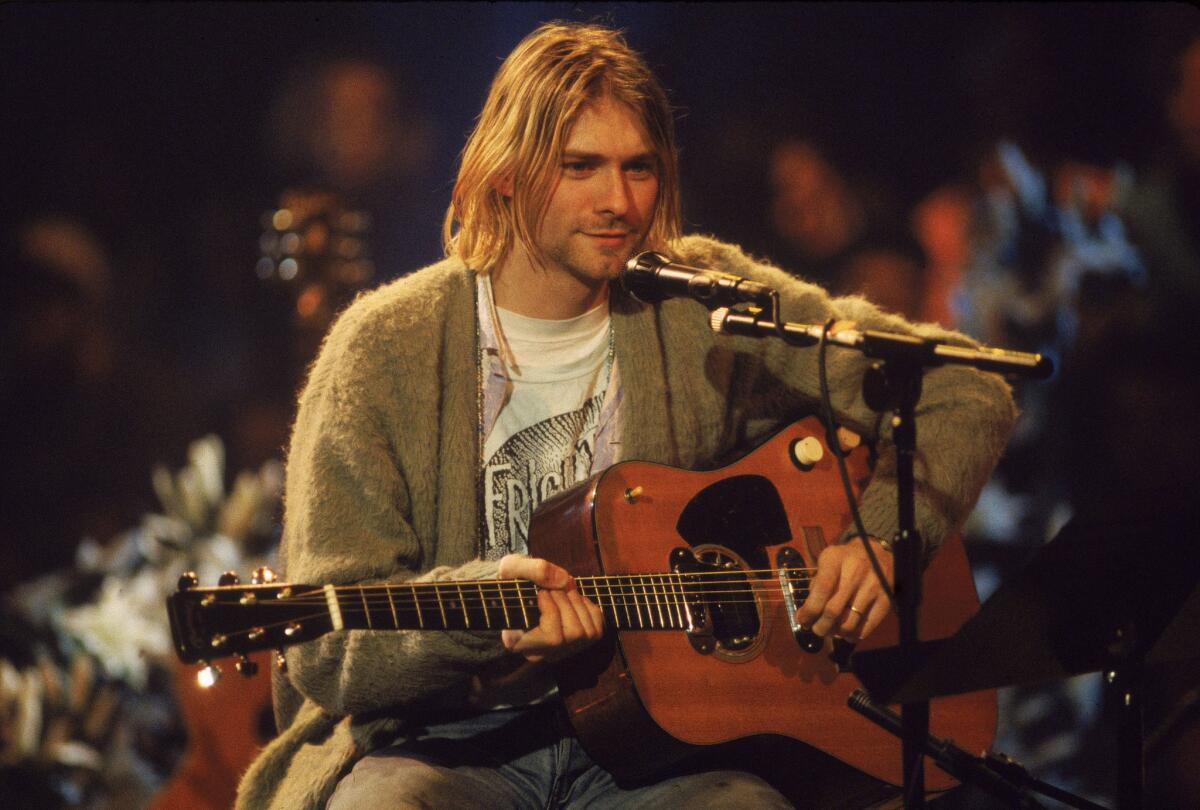

Nirvana singer and guitarist Kurt Cobain performs in 1993 in New York during a taping of “MTV Unplugged.”

It’s been 25 years since the suicide of rock icon Kurt Cobain, and his legend continues to loom large, with Nirvana inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2014 and a documentary about the musician released in 2015. Here’s an appreciation of the artist we published on April 9, 1994, just days after his death:

Kurt Cobain hated being called a spokesman for a generation -- even though he was.

His tales of youthful alienation, especially the massive 1991 hit “Smells Like Teen Spirit,” changed the direction of contemporary rock, but Cobain didn’t feel he was worthy of being a hero.

A deeply sensitive man blessed with a songwriting grace that has been compared to Bob Dylan and John Lennon, Cobain, 27, was found dead Friday in his Seattle home, an apparent suicide victim.

When “Nevermind,” the album containing “Smells Like Teen Spirit,” made him rock’s most acclaimed new singer-songwriter in years, he found it hard to adjust to the sudden acceptance. He felt as confused and troubled as any of the millions of young people who bought the albums he made with the band Nirvana.

He had gone through a difficult childhood, growing up in Aberdeen, Wa., without much self-worth or hope as he was shuttled between relatives -- until none would take him and he sought refuge in the homes of friends or, for a while, under a bridge.

“Nevermind” sold nearly 10 million copies around the world and led critics to draw the parallels with Lennon and Dylan -- both in terms of craft and impact.

His uneasiness as a role model and star wasn’t an act. At times, he simply retreated and pretended no one paid attention. But other times, he felt the burden of that responsibility.

The first time I met Cobain was in the fall of 1992. He hadn’t done an interview in months, but was troubled by recurring rumors that identified him and wife Courtney Love, the rock singer and songwriter, as drug addicts.

He said he had run into a teen-ager who was on heroin at a club in Orange County a few nights before and the kid nodded at Cobain as if they were mates because of their drugs.

“We had a lot of young fans and I don’t want to have anything to do with inciting drug use,” he said in a soft, fragile voice that contrasted with his howling intensity on stage.

He then admitted using heroin in the past, but said he was doing it no longer. Referring to the couple’s then 4-week-old daughter, he added, “I don’t want people telling her that her parents were junkies.”

In another interview last fall in Seattle, Cobain seemed uncharacteristically optimistic. “Once something like marriage and a baby happens to a person, you find a lot of strength that you didn’t know you had,” he said.

To the outside world, things continued to go well for Cobain. “In Utero,” Nirvana’s 1993 follow-up to “Nevermind” was another acclaimed best-seller.

But the rock world braced for the worst last month when Cobain was found in a near-fatal coma in his hotel room in Rome -- a result of a combination of tranquilizers and alcohol.

After returning to Seattle, in the loneliness of his home, he apparently gave up on himself.

To many who weren’t touched by his music, he will be dismissed as another rock ‘n’ roll stereotype . . . a guy who was more lucky than talented, more indulgent than tormented.

But he was so much more.

In a pop world filled with pretenders and opportunists, Cobain was the real thing -- a unique and invaluable voice.

Unlike the conscious, literary edge of Dylan’s work, Cobain tended to write in a fragmented manner that made him the almost ideal poet for this dysfunctional age.

His words could be shocking.

“I wish I could eat your cancer, when you turn black,” sounds ugly and exploitative, but it was an attempt to express the almost irrational desperation of love. The line was written after he watched a TV documentary about a child with a terminal illness.

Elsewhere in his songs, he could be disarmingly personal (“I tried hard to have a father/ But I only had a dad”) or stingingly sarcastic (“I wish I was like you / Easily amused”).

In an interview Monday, his wife Courtney Love told me she worried about Cobain --reminiscing between tears about the time she first heard his recording of “In Bloom,” a song from the “Nevermind” album. (The interview was for a profile of Love that will appear in Sunday Calendar, which was printed before Cobain’s death was known.)

“I was in England and depressed . . . listening to a lot of Aretha Franklin and the Staple Singers -- just music to make me feel better,” she said.

“When I heard the song, I felt his voice . . . that presence . . . that sadness. You know the idea (that someone once wrote) that every abused child in America bought Nirvana’s album? It’s so right. I felt a comfort and soul in his voice . . . a solace that I needed.”

It’s a voice that is now gone.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.