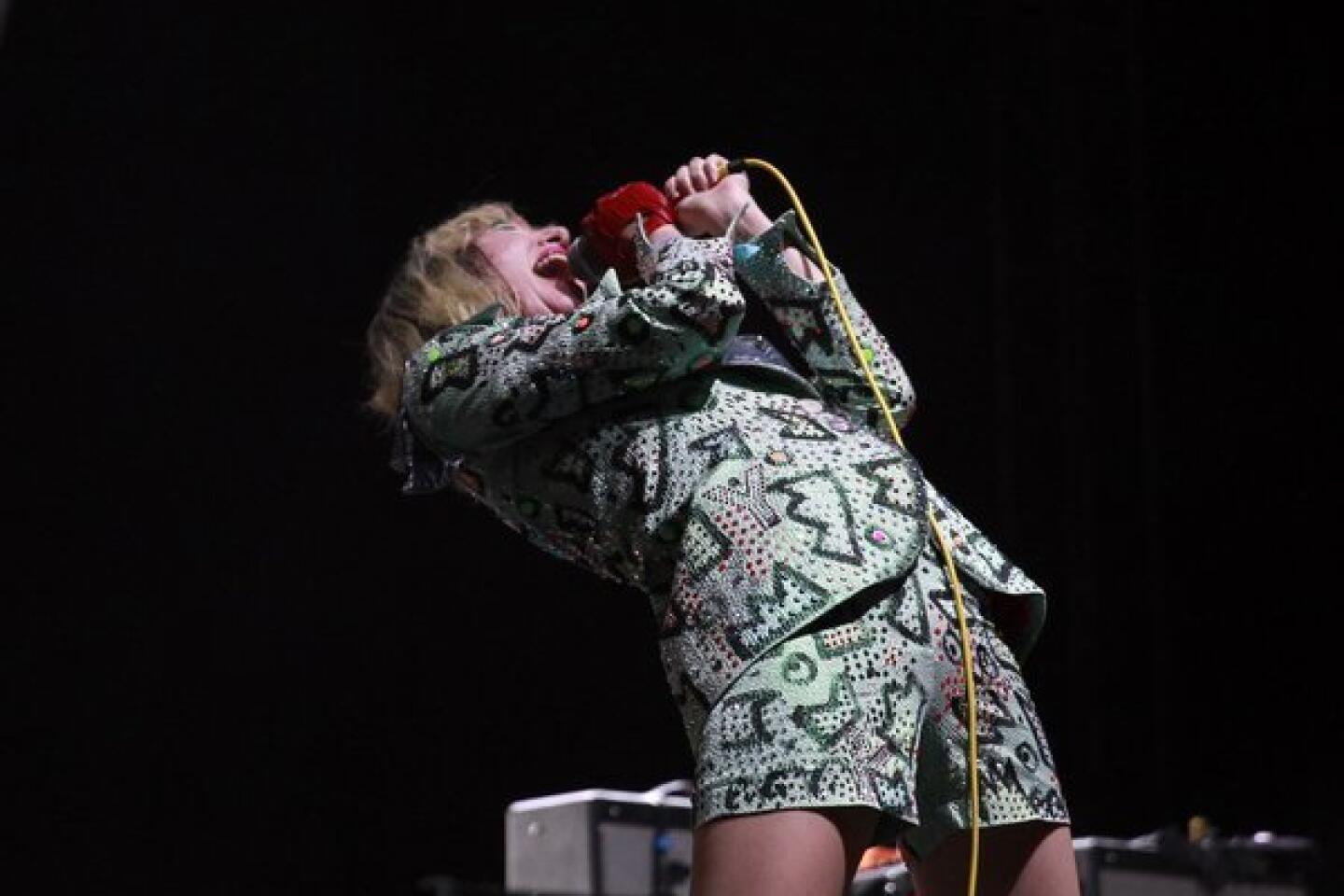

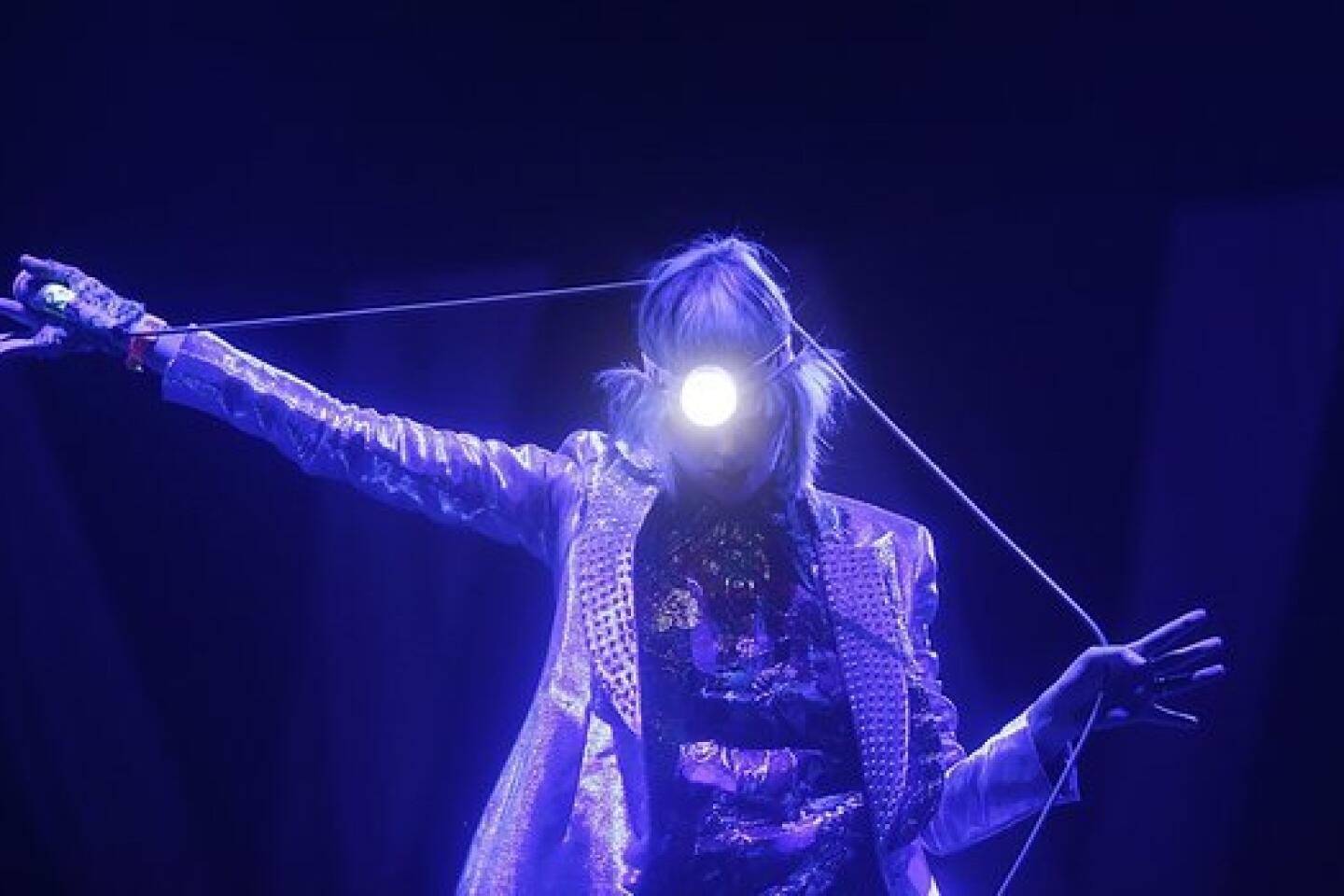

Julia Holter is at the center of her own swirl of sound

While working on her well-received 2012 album “Ekstasis,” Los Angeles singer-composer Julia Holter crafted a song that was such a departure that she set it aside. The piece, “Maxim’s II,” was inspired by a famous scene in the 1958 movie musical “Gigi” and is one of the hubs of her striking new album, “Loud City Song.”

In the film, as the titular heroine very publicly moves through the fancy Parisian restaurant Maxim’s with her scandalous beau, the entire room takes note. “Everyone’s staring at her and gossiping about her when she walks in,” said Holter while sitting on a park bench near Levitt Pavilion Pasadena. “I don’t know why, but I wanted to re-create this scene in a song.”

Five-plus minutes of swirling brass, strings, piano and Holter’s cool, Chet Baker-suggestive vocal, “Maxim’s II” variously suggests an avant-garde classical piece or Phil Spector’s famous wall of sound being imploded. Cymbals crash, tenor and alto saxophones battle and, near the end, Holter ties it all together with a chaotic crescendo. Movie musical material it’s not. Rather, the piece is a monumental construct and unlike any song you’ll hear all year.

RELATED: Best albums of 2013 so far | Randall Roberts

The whole of “Loud City Song,” which comes out Tuesday, is as assured, and it cements Holter as one of the most accomplished — and challenging — young musicians working in the city. Her first release for the respected British label Domino, “Loud City Song” features 10 pieces loosely based on themes explored in “Gigi.”

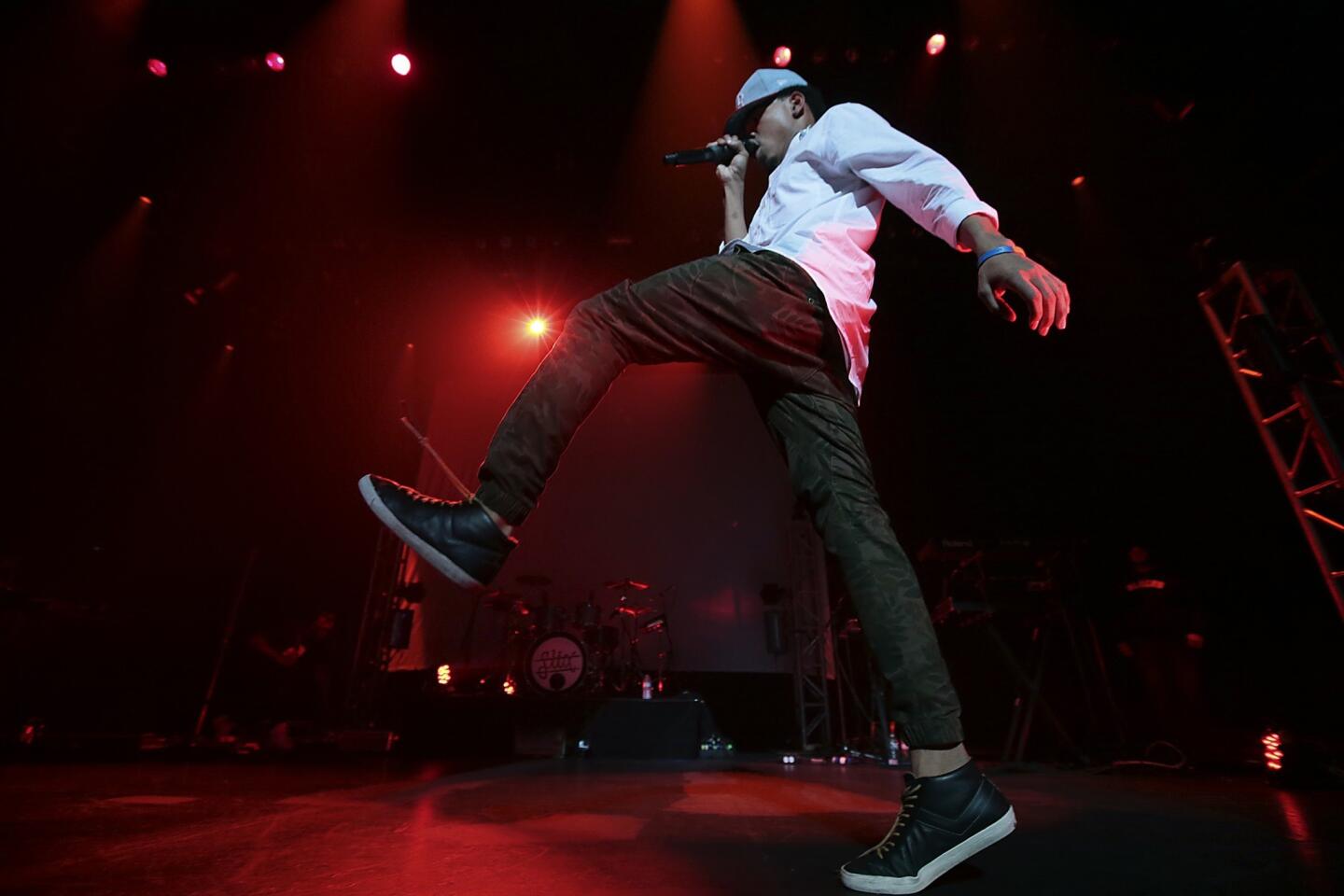

“There’s a social dynamic going on between the individual and the people watching — the voyeurs — and to me that was an interesting dynamic,” she said. Behind her at the Pavilion, a crowd was gathering to witness Holter perform with experimental folk singer Linda Perhacs.

Whether she’s aware of the connection or not, Holter is the center of a similar — though far less gossipy — gaze. An L.A.-born artist whose last album landed on many critics’ best-of-the-year lists (including mine), her new album is her first with a production budget to equal her vision, and a growing collection of fans awaits its release.

The result is a confident — if at times atonal and obtuse — work, the creation of a 28-year-old artist whose recordings can be both head-scratchingly “difficult” while conveying a singular kind of beauty. In committing to Domino, she joins a roster that includes big names such as the Arctic Monkeys, Animal Collective and Hot Chip as well as more experimental kindred spirits such as Dan Deacon, Four Tet and Velvet Underground co-founder John Cale.

TIMELINE: Summer’s must see concerts

Her vision was given structure at the California Institute of the Arts, where Holter studied music composition and developed creative relationships among influential art collective Human Ear Music, whose members included musicians Ariel Pink, John Maus and Ramona Gonzales of Nite Jewel.

In 2010, she began releasing the bedroom and small-studio recordings that would constitute her first full-length projects. “Cookbook” is a 40-minute sound collage based on a John Cage work called “Circus On.” “Tragedy” was inspired by Euripides. “Ekstasis” is less thematically connected and suggested a turn toward more traditional pop structures.

Each was recorded humbly but majestically, with grand, gothic echo and extended explorations that suggested a kinship with both the Medieval liturgical songs of Hildegard von Bingen and British art-pop chanteuse Kate Bush.

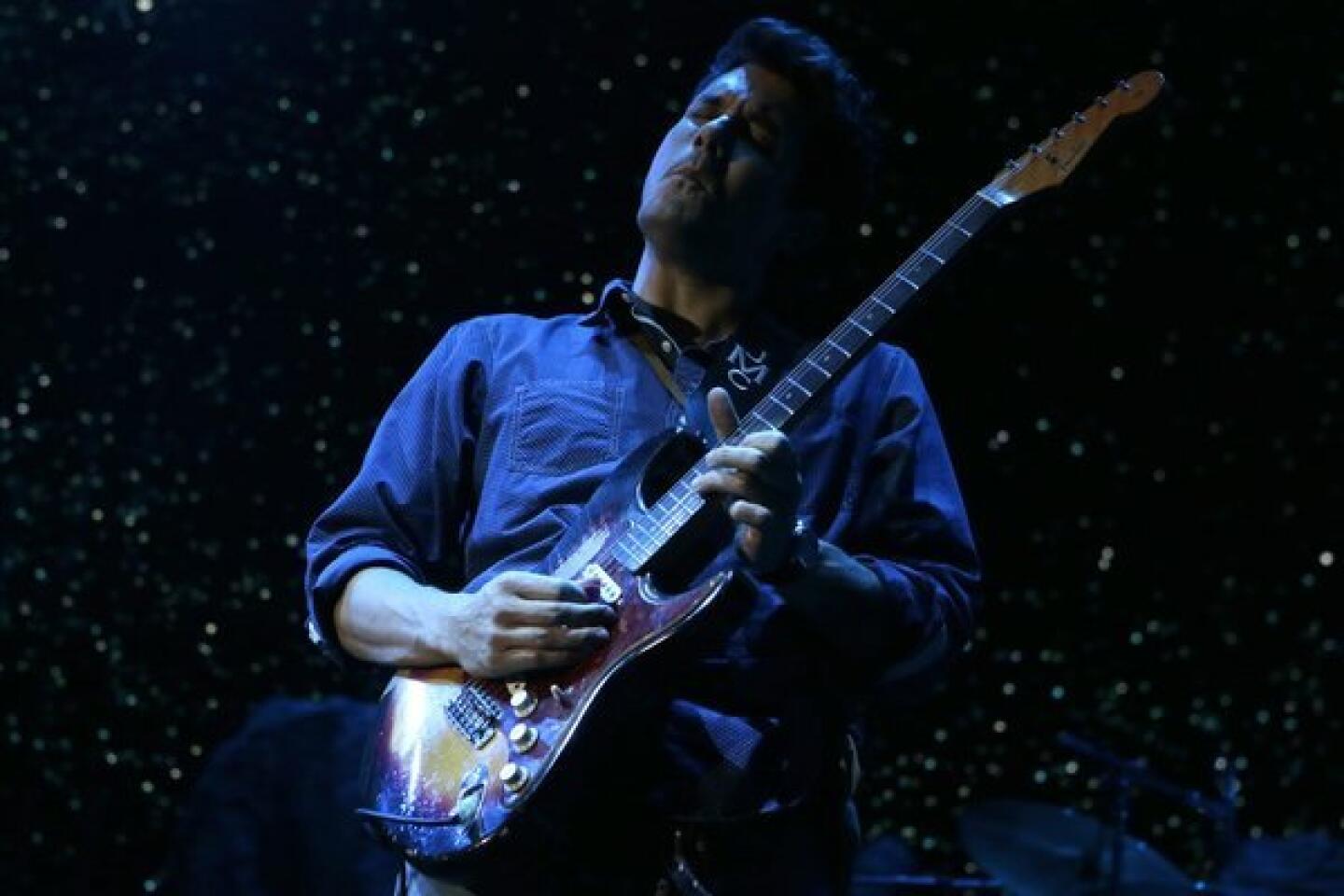

This approach continued for “Loud City Song,” she said. Holter, whose primary instrument is piano, composed detailed sketches as demos at her home in Echo Park. Rather than mix and master these handcrafted works and release them as she’d done in the past, though, she hired producer Cole Marsden Greif-Neill, whose day job is as Beck’s engineer and who has collaborated with Nite Jewel’s Gonzales (to whom he is married) and Ariel Pink’s Haunted Graffiti.

Holter described the situation as “the best of both worlds.” She was working in a studio with a producer and talented instrumentalists to embody “Loud City Song,” “but I was also able to do a lot of things at home. I wrote it all at home, and I came up with a lot of ideas by recording demos.”

On the phone while commuting to Beck’s studio, Greif-Neill said that when he and Holter were preparing to record she handed him demos that he calls “fully formed. The instant I heard it I knew. I saw how vast the world she was writing about was. When she used a string-patch on her synth, I could see a full orchestra underneath. I saw into how expansive the vision was.”

He said that he and Holter were recently looking at his early notes on these foundational recordings, and his first reflex offered insight. “They were mostly, ‘Can we keep this?’ And I kept writing that. That’s something that we both enjoy: that initial moment of creation in a demo. Something left in the demo stage has that raw quality, when the human touch is so palpable.”

A clash between clarity and fog permeates “Loud City Song,” a recording wide with sonic space that rejoices as much in moments of silence as with enormous arrangements. The minimal eeriness of “World” layers Holter’s voice dozens of times to create a choir. “Maxim’s I” swirls amid cymbals and what feels like a cathedral full of cellos and organs — only to halt midstream and spin into a snare-drum-led march before moving back into a velveteen groove.

Set in the middle is the record’s only non-Holter penned song, a floating, drumless version of “Hello Stranger,” a soul song made famous in 1963 by Barbara Lewis. Holter blends a mysterious electronic hum with the rumble of a strummed contrabass, and the competing tension creates a feeling of music untethered. Thematically, Holter said, the song reminded her of a relationship among an aged couple in “Gigi.”

“The whole song — there are no concrete details. ‘I’m so glad you’re here again. Please don’t treat me the way you used to.’ But that’s pretty much the only detail you get,” she said. “It’s wonderfully vague, really.”

Holter, by contrast, speaks directly when it comes to her work. While sitting in the Pasadena park, a nearby homeless man started screaming obscenities at random passersby, which continued for the next 10 minutes. But other than a pause to acknowledge the strangeness, Holter tuned out the drama.

Holter said she prefers to work with both acoustic and electronic tones. “Not as a principle, but I find that I do want, when I’m recording, to have this particular sonic power that you can only get by blending those two things.” On earlier works, she added, she compensated for a lack of acoustic instrumentation by layering the only non-electronic sounds she had at her disposal: voice, harmonium, piano and touches of cello drones.

The freedom in having eight expert players was liberating for everyone, Greif-Neill said. As he and Holter envisioned it, though, the musicians were just part of a template that included “using bits of the demos, using bits of field recordings she’s done, going into the studio and properly recording good players — and then combining that whole thing.” The poppy “This Is a True Heart,” for example, features jazz-inspired stand-up bass, tenor sax, richly layered voices, a midsong breakaway to the sound of footsteps in an echoed room and a tiny synthetic high-hat beat.

Greif-Neill said watching Holter work in a full studio after mostly confining herself to computer-based recording was a lesson in artistic clarity. “She’d never been in a situation like that,” he said, “where she was able to be in the studio and to be directing these musicians. Even extremely confident people sometimes bend and doubt themselves, but her confidence with her own music — it did not seem to affect the process.”

Nor does her confidence waver onstage, he added, noting that he and Gonzales had performed on a bill with Holter and witnessed her effect. “Honestly, we were in Poland last week, and I was blown away by how her music appeals to people. To me it’s so truly esoteric, so very strange — and even academic — at times. But seeing the festival audience of thousands of people — everybody sort of dancing, swaying a little bit to her music. I’m still very blown away that it has such a wide appeal.”

Holter will return to Los Angeles to prepare for her fall tour, which begins on Sept. 11 in Los Angeles at the First Unitarian Church. From there, she’ll perform dates in San Francisco, Minneapolis, New York and elsewhere before heading to Scandinavia for a set of concerts.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.