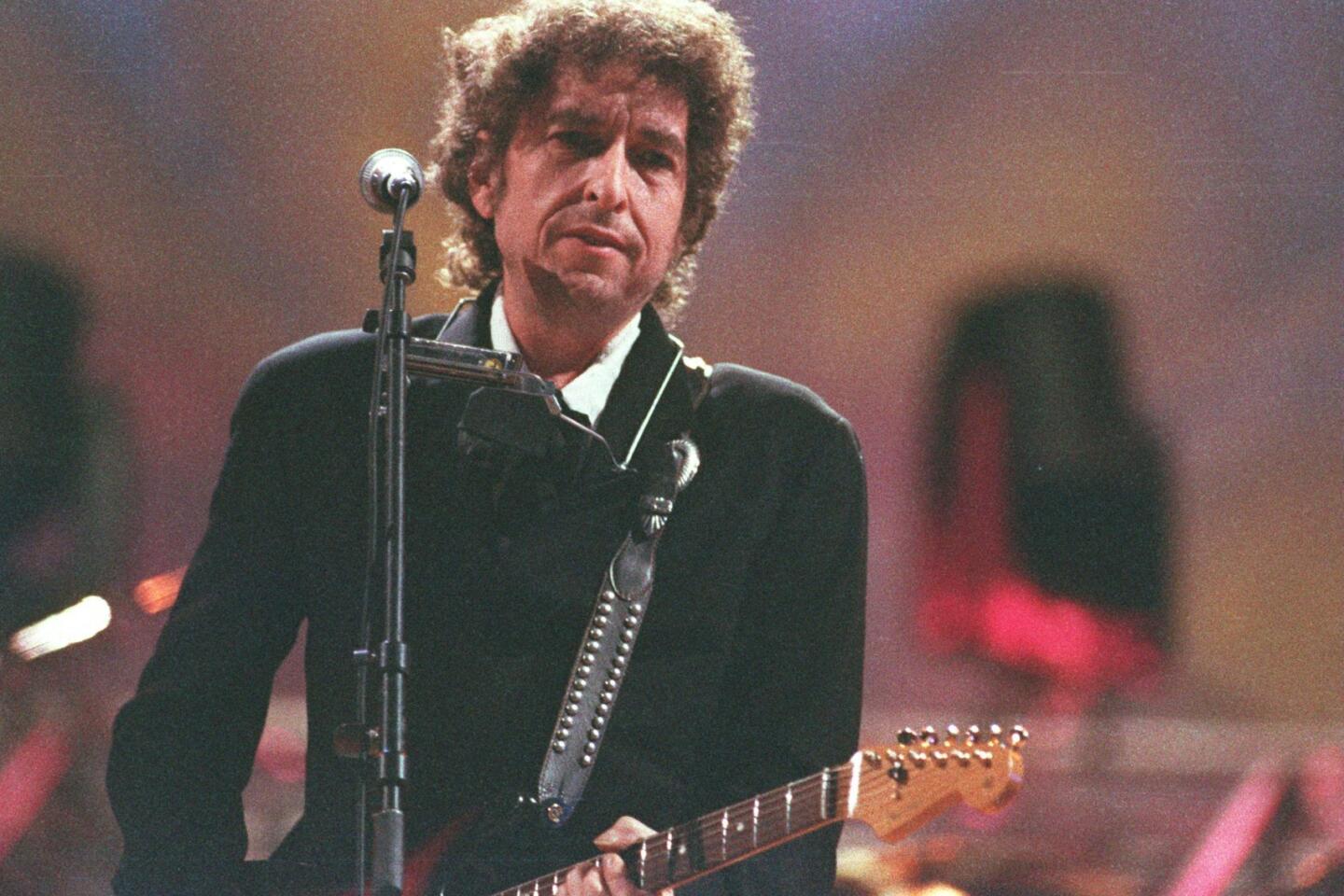

Review: ‘Bob Dylan 1965-1966’ opens window on a creative peak

Editor’s note: In what was considered a “radical” choice, Bob Dylan was announced as the winner of the Nobel Prize in literature on Oct. 13, 2016. Read the story here.

Among the many things Thomas Edison famously said, he remarked that “Genius is 1% inspiration and 99% perspiration,” and he also insisted that “I have not failed once. I have simply found 10,000 ways that do not work.”

Both precepts are clearly evident in “Bob Dylan — The Cutting Edge 1965-1966: Bootleg Series Vol. 12,” the revelatory latest release of Dylan archival recordings that comes out Friday, Nov. 6.

Culling a mind- and ear-boggling wealth of outtakes, alternate versions and rehearsal snippets during sessions over the 14 months of an astonishingly fertile period for Dylan, which yielded three of the most influential albums in rock history — “Bringing It All Back Home,” “Highway 61 Revisited” and “Blonde on Blonde” — the new set throws open a panoramic window into the creative process of one of the 20th century’s greatest artists.

SIGN UP for the free Essential Arts & Culture newsletter >>

The album is being released in multiple formats: a two-CD/three-LP “Best of the Cutting Edge” with 36 tracks, mostly alternate takes of the finished recordings from each album; a six-CD deluxe version including multiple takes of many of the period’s signature songs; and the 18-CD limited edition “collector’s” version ($599.99, available only at www.bobdylan.com) with every moment recorded in all those studio sessions.

The “best of” collection is the equivalent of a snapshot, piquing listeners’ curiosity with individual examples of different approaches Dylan took before settling on final versions of such landmark songs as “Like a Rolling Stone,” “Mr. Tambourine Man,” “Highway 61 Revisited,” “Desolation Row,” “Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues” and “Visions of Johanna.”

The deluxe version is where things get truly fascinating, with three, four, five and in some cases more versions of numerous songs showing how much perspiration Dylan and the musicians in the studio with him were willing to bring to the moments of inspiration that gave him the core music and lyrics.

Songs are often worked out in different tempos, meters and keys, with accompaniment ranging from solo acoustic guitar or piano to blazing full rock band support as Dylan strives again and again to discover the ideal arrangement and mood for each composition.

The piece de resistance is the third disc, which comprises 20 takes, recorded over two days, of his monumental 1965 hit “Like A Rolling Stone,” which topped a list of the “500 Greatest Songs of All Time” as ranked in 2011 by Rolling Stone magazine. (Not that there’s any reason to suspect self-promotion in the choice, but we’re infinitely grateful that list wasn’t assembled by Virgin Airways magazine.)

For anyone remotely interested in how great art is made, this is the equivalent of an audio master class as Dylan works, reworks and reworks again the song until it sonically captures the energy, defiance, outrage, empathy, celebration and liberation embedded in the lyrics.

The song starts in Take 1 with full band accompaniment, but it’s played as a waltz, which isn’t as odd as it might sound, given the cadence of his lyrics. But in that three-beat pulse, it’s a dance rather than a declaration of spiritual independence.

A long harmonica introduction that quickly breaks down when Dylan begins to sing as the band tries to figure out the song’s structure. Dylan is heard saying it should be “a little bit slower, and softer.” Organist Paul Griffin is contributing mostly chunky chords behind the piano and guitarist Mike Bloomfield arpeggiated fills.

Early in the process, he sings “You used to make fun [instead of ‘laugh’] about/Everybody that was hangin’ out.” He also hasn’t settled on the famous chorus “How does it feel … to be out on your own/No one known/ Like a rolling stone.”

“My voice is gone,” he croaks after the fourth take. “Want to try it again?”

These sessions came at the end of a day of recording for the “Highway 61 Revisited” album, and the group called it quits after five passes late that night.

The next day they reconvened, this time with Al Kooper taking over on the organ. Kooper was a guitarist who’d hoped to crash the sessions and work with Dylan, but he reportedly was awestruck hearing what Bloomfield was playing and shifted to the organ instead.

Dylan has now decided to try the song with a 4/4 rock beat, dropping the key down a half-step from C# to C — “the people’s key,” as it’s often called.

Bloomfield is discovering the slightly distorted backing figure that would become one of the song’s musical signatures, and Kooper is experimenting with single note organ lines rather than the chords Griffin had been playing, but they’re still unfocused. Dylan’s harmonica also is anonymous chording.

On the third take during the second day, we first hear the sharp snap of Bobby Gregg’s snare drum to start the song instead of Dylan’s guitar strum or Frank Owens’ piano notes that have launched it previously. And Kooper is still timidly lurking in the background trying different organ parts.

Take 4 on Day 2 is where all the elements coalesce into the version that appeared on the album, yet they continued with 11 more takes trying other ideas — faster tempo, less organ, less guitar (“Is my guitar too loud?” Dylan asks at one point, clearly more interested in the big picture than his own instrument being front and center), bass higher in the mix, piano more prominent and Dylan’s varied vocal phrasing on the verses, then the choruses.

It’s akin to watching the team of workers who had to assemble the Statue of Liberty in 1885 after the government of France shipped it across the Atlantic in hundreds of pieces. When Kooper finally hits on the organ motif that answers Dylan’s query “How does it feel?” it’s like the lighting of Liberty’s torch.

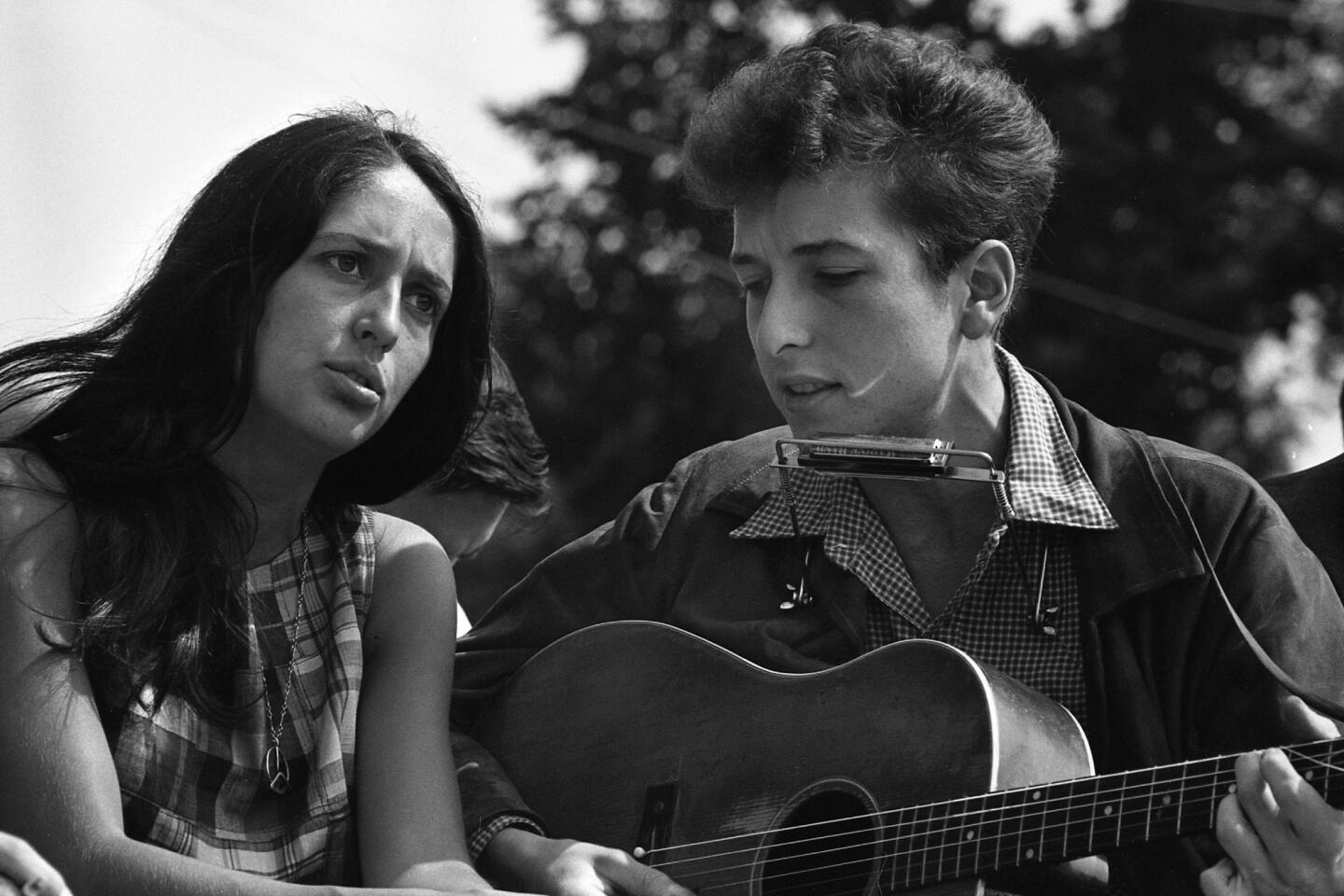

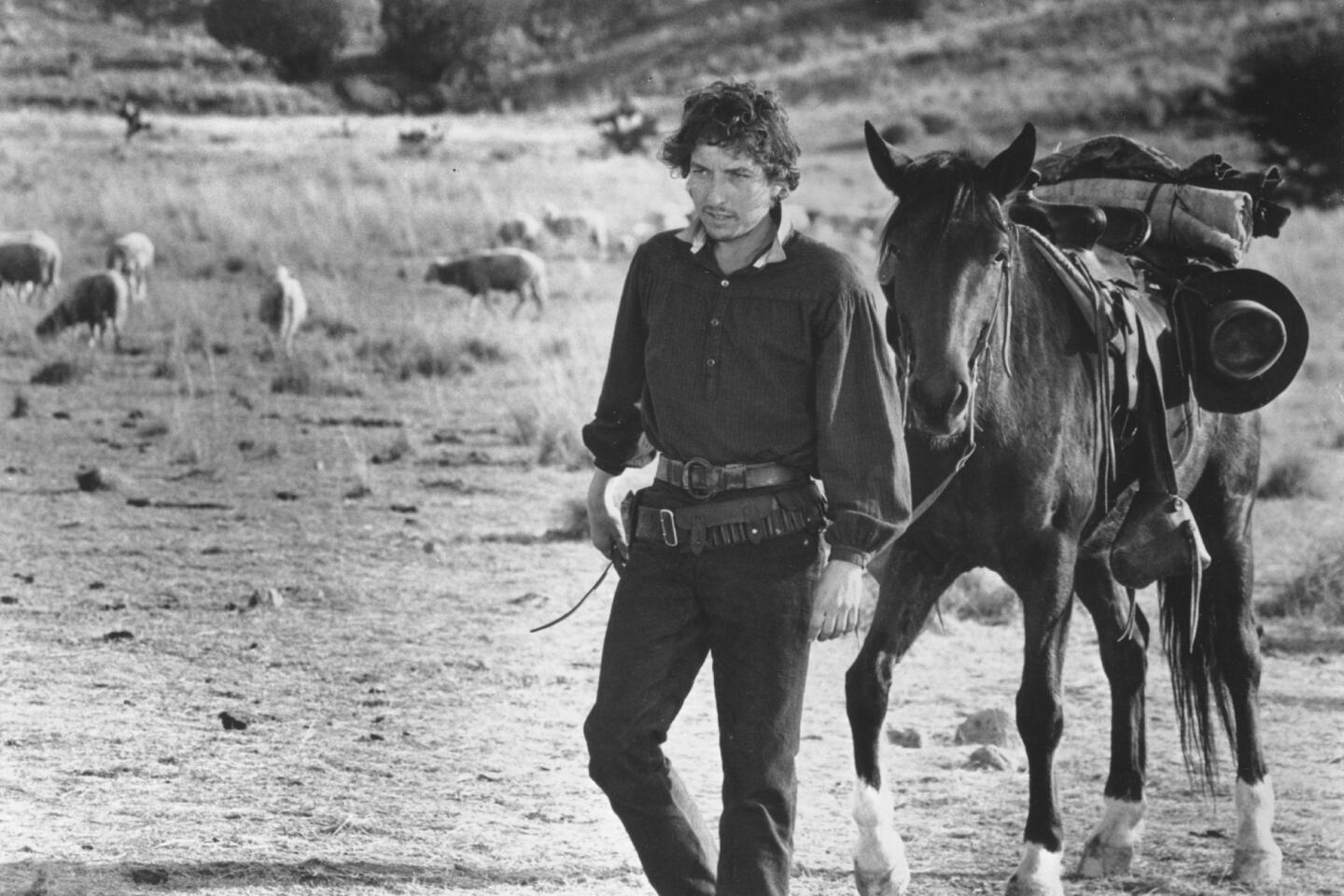

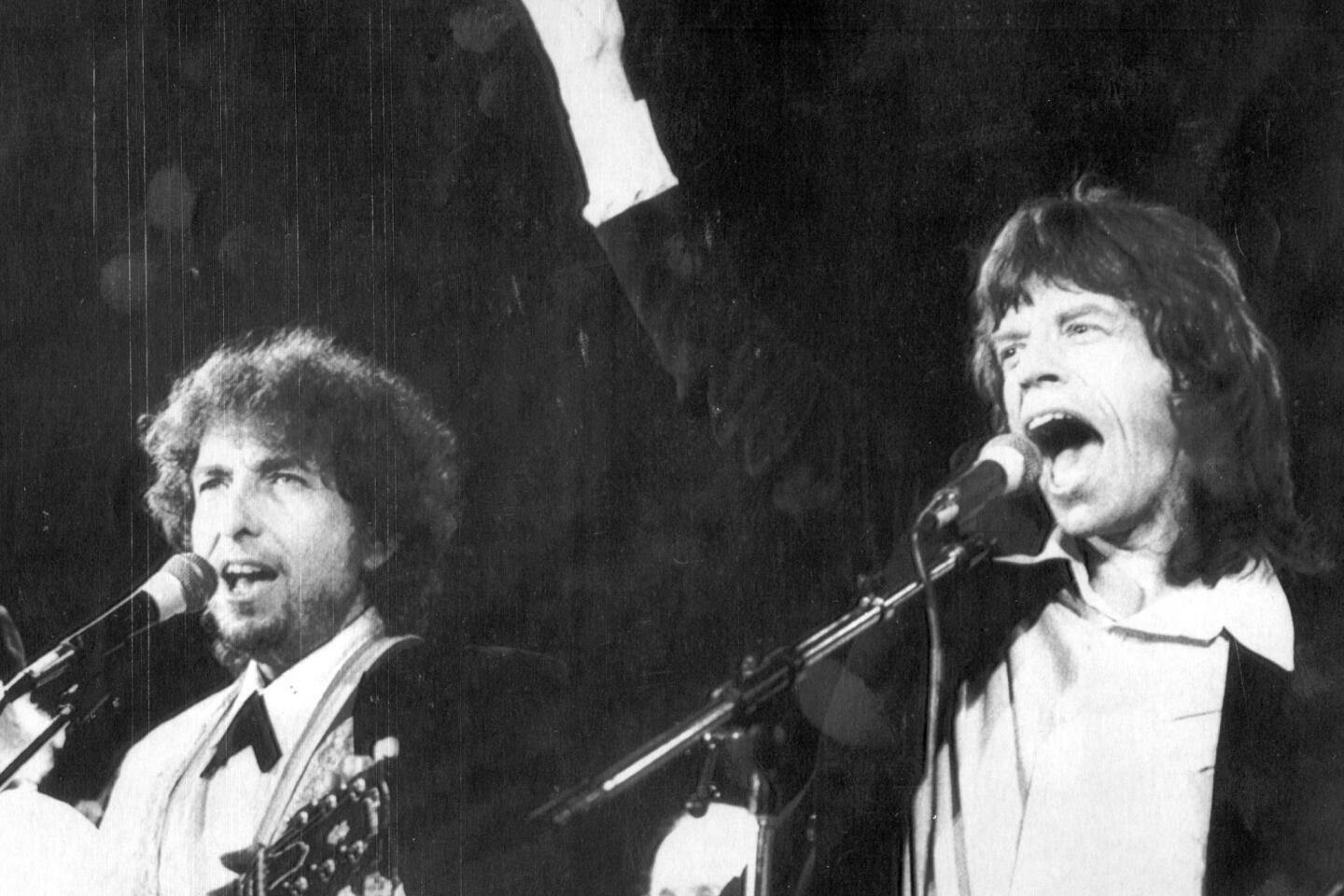

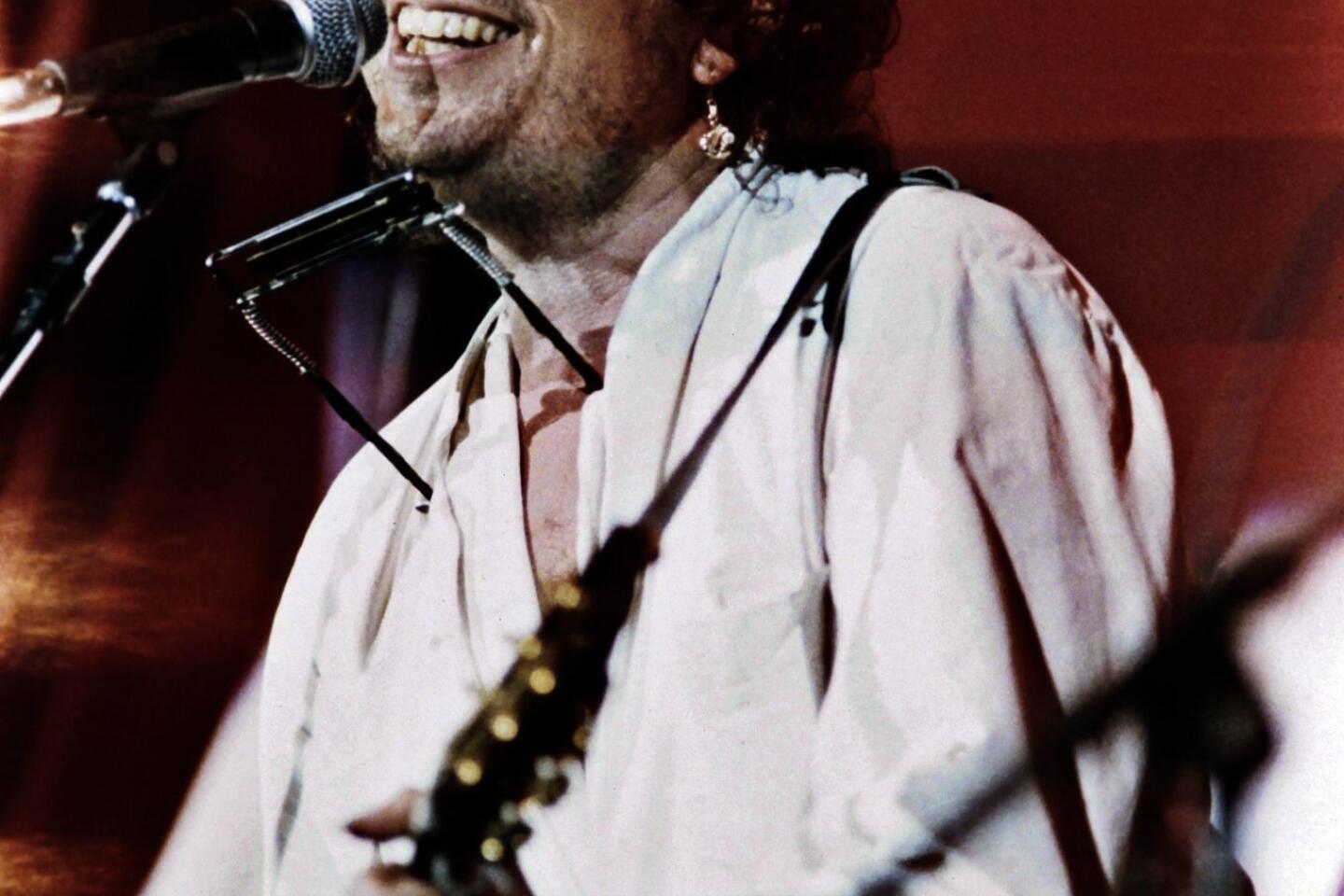

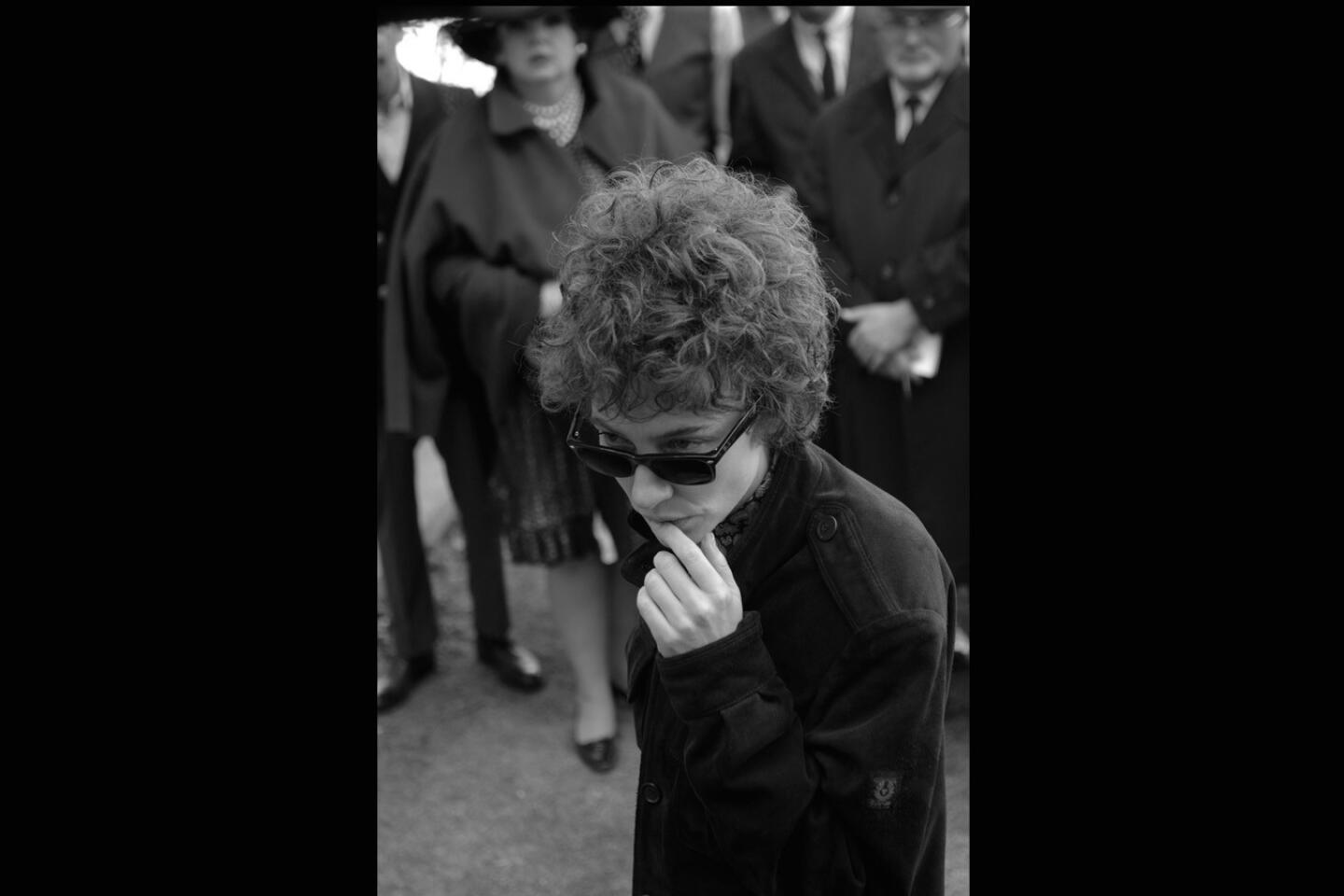

A brief look at the catalog of Bob Dylan.

The final four tracks on the “Like a Rolling Stone” disc are split into the individual stems from the four-track recording: one with Bloomfield’s guitar, another with Dylan’s vocals and his own guitar, a third with piano and bass, the fourth with the drums and organ parts.

Dissecting the track again proves the notion of a whole sometimes being greater than the sum of the parts.

There’s a sense of musical inevitability that emerges across the multiple takes of “Like a Rolling Stone,” but elsewhere in the sessions there’s an equally powerful argument for the malleability of art.

Although Dylan rejected attempts to record “Visions of Johanna” with backing from most of the members of the Hawks, who would in a few years become better known as the Band, there’s a rollicking version in Take 5 that, to this listener’s ears, is every bit as valid as the more laid-back recording he made in Nashville with session pros and chose to release on “Blonde on Blonde.”

An early stab at “Stuck Inside of Mobile With the Memphis Blues Again” uses a rock-swing feel, and Dylan sings “Oh mama, this might be the end, I’m stuck inside of Mobile with the Nashville blues again.” Then he tries a solid rock four-beat, an approach he stays with for several more takes before shifting gears to the rolling gallop that became its rightful rhythm.

On the “Bringing It All Back Home” and “Highway 61 Revisited” sessions, he’s frequently heard interacting with producer Tom Wilson, who will ask “What’s this one called, Bob?” to which he often receives outlandish spur-of-the-moment responses such as “Uhhh, ‘Bank Account Blues.’” Producer Bob Johnston had taken over for Wilson, for reasons still unknown, when Dylan started recording “Blonde on Blonde,” much of which was completed after he shifted from New York to record in Nashville.

In addition to the even greater depth that all these experiments are presented in on the 18-CD collector’s version, which is being limited to 5,000 copies, the entirety of disc 18 demonstrates Dylan’s passion for country, blues and folk music in songs recorded in hotel rooms during various tours Dylan did in 1965 and ’66.

We hear him sing Scott Wiseman’s “Remember Me” and Merle Kilgore and Webb Pierce’s “More and More,” Hank Williams’ “I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry” and traditionals such as “Wild Mountain Thyme.”

They testify to his solid grounding in roots music styles well before he hunkered down with the Band at Big Pink in New York following the 1966 motorcycle accident that took him out of circulation for months, during which they recorded the mountains of old and new material that later surfaced in “The Basement Tapes.”

That, of course, was rock’s first massively circulated bootleg album, and because his outtakes had been widely disseminated by bootleggers and pirates, Dylan and Columbia Records decided to serve them up in more intelligently and authoritatively assembled packages starting in 1991 with the first officially sanctioned “Bootleg” series release.

All the versions of “Bootleg Vol. 12” also include insightful essays from rock aficionados and Dylan specialists Bill Flanagan and Sean Wilentz, and the collector’s edition also comes with new pressings of all nine singles released during that period, including “Positively 4th Street,” the deliciously stinging hit that never made it onto any of those albums.

The deluxe edition comes with a 120-page book filled with period photos and facsimiles of typed and handwritten lyrics showing the evolution of various songs as Dylan was modifying them.

Whether Dylan ever spent much time studying Edison isn’t clear, though the Bard of Hibbing, Minn., obviously shares an affinity for the invention Edison considered his favorite of all the gadgets he developed: the phonograph.

But the release of “The Cutting Edge” recordings proves Dylan to be fully in sync with another of Edison’s seemingly endless string of pearls of wisdom when he said: “Our greatest weakness lies in giving up. The most certain way to succeed is always just to try one more time.”

Follow @RandyLewis2 on Twitter. For more on Classic Rock, join us on Facebook.

ALSO:

Elvis Presley ‘If I Can Dream’ with orchestra misses the mark

‘Sinatra: An American Icon’ is a deep look into Ol’ Blue Eyes at Grammy Museum in L.A.

Adele on her new ‘25’ album: ‘Sorry it took so long’

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.