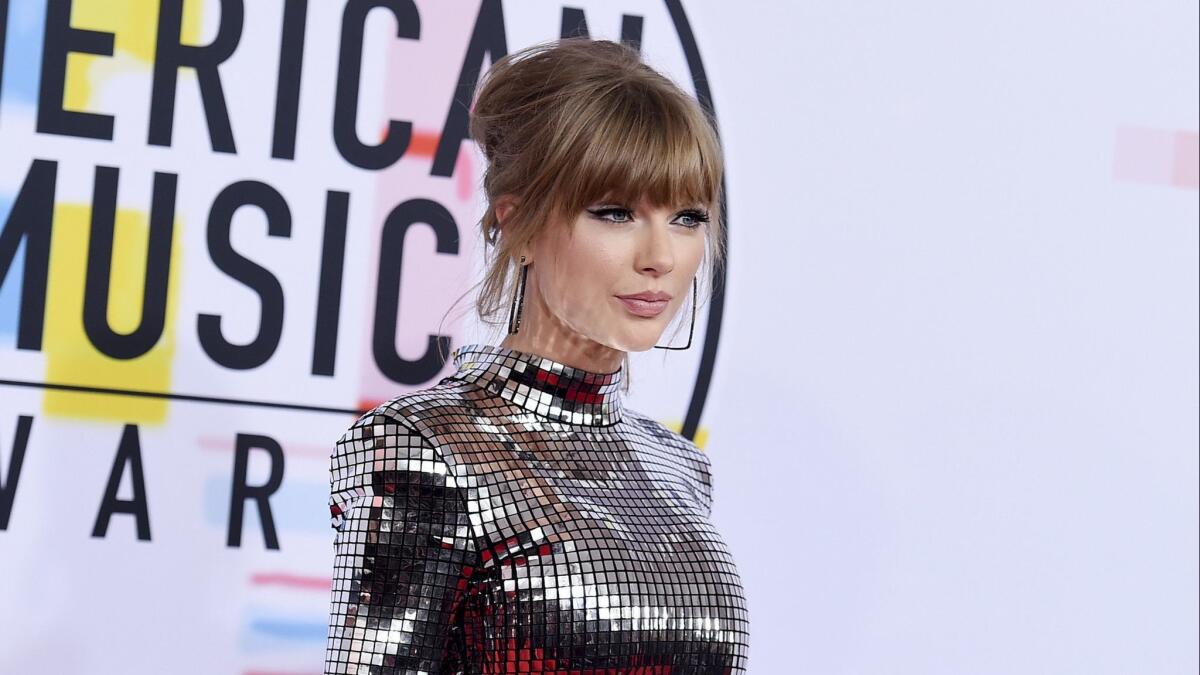

Taylor Swift, entitled millionaire, is the labor activist the music industry needs

Taylor Swift, one of pop music’s most polarizing superstars, is enmeshed in another very public battle, and the world has promptly, predictably, divvied up into pro- and anti-Swift camps.

This time, however, the target of her ire isn’t an ex-boyfriend or another musician with whom she has clashed, but super-manager Scooter Braun. Braun has assembled an investment group that’s entered into a deal, announced over the weekend, to pony up $300 million to buy her former record label and with it, the master recordings to all her existing studio albums.

Swift is incensed, as millions of her social media followers learned from her angry Tumblr post last weekend, that Big Machine Label Group chief Scott Borchetta chose to sell his company to Braun, who once represented Swift’s arch-nemesis, Kanye West.

Describing the deal as “my worst nightmare,” Swift wrote that she is “sad and grossed out” that Braun will take over the indie company that launched in tandem with Swift’s debut album in 2006.

“Essentially,” she wrote on Sunday, “my musical legacy is about to lie in the hands of someone who tried to dismantle it.”

Once again, the public has responded vociferously, with the pro-Swift faction rallying to her defense and lauding her as a fierce advocate for artists’ rights, while the anti-Swift contingent painted her as a super-rich celebrity socialite bemoaning her latest perceived injustice.

The battle with Braun and Borchetta, however, aligns with her track record over the last dozen years of targeting a succession of foes of increasingly potent stature, from tech giant Apple to the coalition of Braun and Borchetta. In the dozen years since she emerged from Nashville as this generation’s most successful singer-songwriter, Swift has consistently spoken out in support of the economic rights of her fellow creatives.

“Hopefully,” she wrote on Tumblr, “young artists or kids with musical dreams will read this and learn about how to better protect themselves in a negotiation. You deserve to own the art you make.”

Swift could hardly have chosen a more imposing opponent to step into the ring with: In addition to West, Braun’s powerhouse client list includes or has included pop stars Justin Bieber, Ariana Grande, Demi Lovato and Carly Rae Jepsen, country duo Dan + Shay, DJ-producer-songwriter David Guetta, R&B singer Usher and even onetime Taylor Swift posse member, supermodel Karlie Kloss.

In the social media scrum that followed Swift’s Tumblr post, sides were sharply drawn. Lovato; Bieber, Bieber’s wife, Hailey Baldwin, and his mother, Pattie Mallette; Braun’s wife, Yael Cohen Braun; and singer-songwriter Sia all defended Braun and Borchetta.

Meanwhile, Swift’s supporters included Cher, Iggy Azalea, Alessia Cara, Haim, Halsey, Gretchen Peters, Panic! at the Disco’s Brendon Urie, supermodels Cara Delevingne and Martha Hunt, “American Idol” alumnus Todrick Hall and reality TV star Spencer Pratt.

Swift expressed in no uncertain terms that she felt bullied by Braun during her public clash with West and his wife, Kim Kardashian, part of the aftermath of the infamous 2009 incident at the MTV Video Music Awards, when West grabbed the microphone from her hand as she was accepting an award and went on a rant supporting Beyoncé.

Swift also informed her followers that a deal Borchetta offered for her to re-sign with Big Machine was ultimately untenable because the terms would have required her to “earn” back the master recordings for her older albums one at a time, in conjunction with the delivery of each new album she would owe the label.

Borchetta pushed back, posting an open letter of his own. “We are an independent record company,” he wrote. “We do not have tens of thousands of artists and recordings. My offer to Taylor, for the size of our company, was extraordinary.”

“Scott Borchetta never gave Taylor Swift an opportunity to purchase her masters, or the label, outright with a check in the way he is now apparently doing for others,” Swift’s lawyer, Donald Passman, said in a statement issued Tuesday.

Representatives for Swift and Borchetta declined further comment for this article.

All this plays out just a few weeks before Swift releases her new album, “Lover,” on Aug. 23 for the Universal Music Group, with whom she signed a new deal last fall after declining to re-up with Borchetta and Big Machine.

On one level, Swift’s latest fight is emblematic of her career. Over time she’s stepped up to challenge adversaries of progressively greater power and influence.

Even before she signed with Big Machine, she (and her parents) held out from among a number of offers she had received to sign a recording contract that both allowed her to use her own songs and to have a hand in producing her records — hardly standard procedure in Nashville, and certainly not for an act still too young to vote.

By the time of her third album, “Speak Now,” released in 2010, Swift decided to take on skeptics who ascribed her success to others — whether her songwriting collaborators, co-producer or record company execs. For that album, she pointedly wrote all the songs on her own, including “Mean,” her response to those who’d thrown barbs her way. (“You have pointed out my flaws again,” she sang then, “as if I don’t already see them.”)

In 2015, with her pop stardom at its zenith, she decided to go head-to-head with the most successful company in the world, Apple, withholding her “1989” album from Apple’s streaming service and challenging the company to revamp its policy that required artists to give up their royalties during a three-month introductory trial period when the tech behemoth was trying to lure new subscribers with a no-cost tryout.

“I respect the company and the truly ingenious minds that have created a legacy based on innovation and pushing the right boundaries,” she wrote in an open letter to consumers, adding, “I’m not sure you know that Apple Music will not be paying writers, producers, or artists for those three months. I find it to be shocking, disappointing, and completely unlike this historically progressive and generous company.”

Apple relented, after which Swift authorized it to stream her album.

Then, as the #MeToo movement began to reach critical mass in 2017, Swift prevailed in a lawsuit she had filed against a Denver disc jockey who had sued her for wrongful termination after she complained to his employer that he had grabbed her bottom during a 2013 post-concert meet-and-greet. The DJ was fired, and then sued Swift.

She countersued, asking the jury for a token $1 judgment on behalf of “anyone who feels silenced by sexual assault.”

“I acknowledge the privilege that I benefit from in life, in society and in my ability to shoulder the enormous cost of defending myself in a trial like this,” she said at the time. “My hope is to help those whose voices should also be heard.”

The jury sided with Swift.

More recently, as her original contract with Borchetta and Big Machine expired, she decided to sign with the UMG-owned label Republic Records. In negotiating that deal, Swift went to bat not only for herself but all other UMG artists.

“There was one condition that meant more to me than any other deal point,” she wrote in an Instagram post last November announcing the deal. “As part of my new contract with Universal Music Group, I asked that any sale of their Spotify shares result in a distribution of money to their artists, non-recoupable.” Billboard estimated that the Spotify payout could be worth an estimated $300 million to UMG acts.

Swift, who was roundly criticized for declining to endorse Democratic presidential candidate Hillary Clinton against Donald Trump in 2016, has, at least publicly, become a more politically engaged citizen of late. Her most recent song and video, “You Need to Calm Down,” featured a dizzying cavalcade of LGBTQ personalities, and was preceded by a letter she posted on Instagram addressed to Sen. Lamar Alexander of Tennessee, urging passage of the Equality Act and criticizing President Trump. In 2018, she endorsed Tennessee Democratic Senate candidate Phil Bredesen, who ultimately lost to Republican Marsha Blackburn.

On Sunday, Swift asserted that her beef with Braun and Borchetta has ramifications beyond the personal, and she hoped to empower young artists to forge better deals than the one she signed when she was a young teenager. That goal, however, may be beyond even Swift’s superpowers. Historically, musicians enter their first recording contracts as unknowns, and record companies gamble on whether they will defy the odds and find breakout success.

“It’s the way the business has been and always will be,” longtime music industry executive and talent manager Jim Guerinot said on Tuesday. “You don’t have leverage when you start out. You get screwed on your first deal, you get it right on your second.”

“The golden ticket,” he said, “is getting the reversion” of ownership of master recordings. “What you have to exchange for that? That’s how you decide whether or not it’s worth it.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.