Review: Stevie Wonder opens up ‘Talking Book’ and ‘Innervisions’ at holiday benefit concert

Stevie Wonder had some altruistic reasons for performing his albums “Talking Book” and “Innervisions” from beginning to end on Sunday night at Staples Center.

For starters, he was using the records, both from his early-1970s artistic peak, to lure folks to this year’s edition of his annual House Full of Toys benefit concert. (Beyond paying for tickets, showgoers were asked to bring unwrapped gifts to be distributed over the holidays to underprivileged families around Los Angeles.)

For another thing, the singer was looking to channel the albums’ positive thinking at a moment when “too many people in high positions are creating negativity,” as he put it in one of the many rambling speechlets that pushed the production toward the four-hour mark.

Yet Wonder wasn’t without a more selfish motivation.

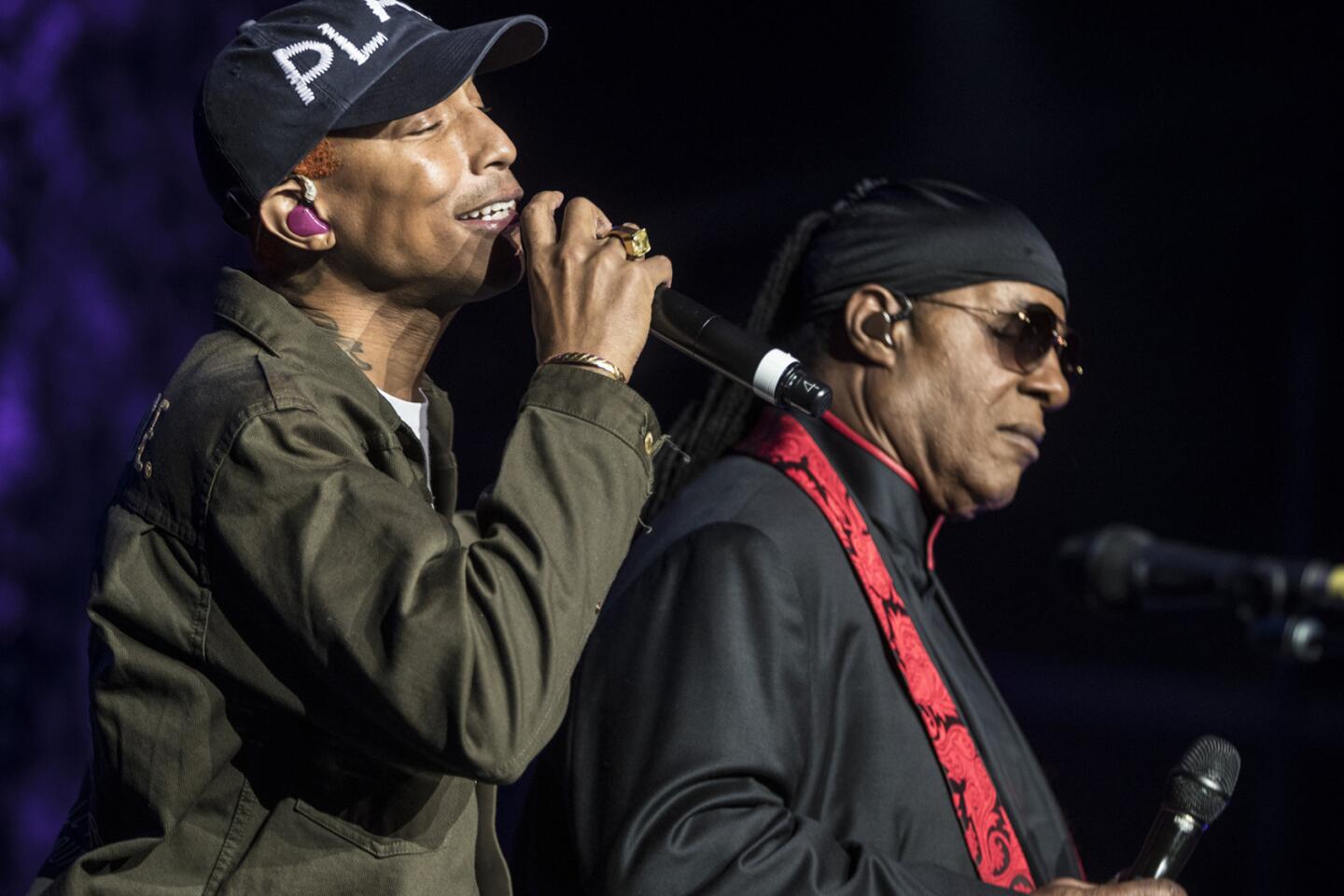

Addressing the crowd before he cracked open “Talking Book” — which itself followed a lengthy stretch of table-setting appearances by Tony Bennett, Pharrell Williams, Dave Matthews and others — Wonder said he was revisiting the old work to see if it still moved him — “to hear if I still like it and to critique what I can’t change,” he explained with a grin.

“Do I still feel that joy in my heart?” he asked. “Am I still optimistic? And when I do ‘Superstition,’ do I still want to get that groove in?”

Only Wonder knows the answers of course.

But you had to admire the thoughtfulness of his approach, especially now that live performances of classic albums, from the Beach Boys’ “Pet Sounds” to U2’s “The Joshua Tree,” have become common catnip for fans more interested in nostalgia than investigation. (Indeed, Sunday’s gig came four years after Wonder did his “Songs in the Key of Life” at 2013’s House Full of Toys benefit.)

Ditto the singer’s commitment to realizing the rhythmic, textural and harmonic sophistication of his early-’70s music, which found him breaking away from the crisp R&B formalism of his youth to embrace the flowing melodies and open-ended structures — and the political activism — of songs like “You and I” and “He’s Misstra Know-It-All.”

At Staples he was backed by a large band led by Rickey Minor, complete with horn section, backing singers and several percussionists; original session players, including guitarist Ray Parker Jr., joined him at various points to reproduce their studio licks (even if a buggy sound system prevented some of them from being heard).

And though the crowd noticeably thinned as the clock ticked past midnight, Wonder stuck to the program, playing the songs in all their complicated, drawn-out glory rather than cutting them short in a race to the finish line.

The result stood out from many of the full-album concerts I’ve seen in that Wonder wasn’t reimagining the material — he was deeply faithful to the old arrangements — but was singing and playing with atypical emotional urgency.

That went double in “Big Brother,” about opportunistic politicians, and the outraged “Living for the City,” with its lyrics about black struggle that Wonder practically growled through clenched teeth as he hammered his keyboard.

Much in America has changed since he released “Talking Book” and “Innversions,” Wonder seemed to be saying. And much else hasn’t.

Twitter: @mikaelwood

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.