From the archives: Read a 1991 Times interview with Chris Cornell on the making of Soundgarden’s ‘Badmotorfinger’

Chris Cornell, a founding member and singer for hard rock bands Soundgarden and Audioslave, was found dead on Thursday in Detroit.

In a 1996 interview with longtime pop music writer Richard Cromelin, Cornell reflected on the success of Soundgarden’s breakout album, “Superunknown.”

After the writer noted a “backlash to that darkness and cynicism — a sort of ‘stop whining’ attitude” among some critics — Cornell responded, in part: “I don’t have any interest in being pessimistic and gloomy all the time just for the sake of it, and I always try to find things to celebrate or be happy about or to feel good about.

“But I’m not living in a cocoon and painting it with bright colors and putting up little fiesta bulbs. I am aware of what’s going on around me enough to be disturbed by it at some point on a daily basis.”

By 1996, The Times had already developed a relationship with the band.

Below, republished in its entirety, is a Soundgarden profile that Cromelin wrote in advance of “Badmotorfinger,” the band’s third album and second for major label A&M after issuing works for indies Sub Pop and SST.

For context, the story was published on Aug. 25, 1991, a month before Nirvana released its era-defining album “Nevermind.”

-- Randall Roberts

Mixing engineer Ron St. Germain stands at a tape machine in a Tarzana studio, twisting the reels by hand until he creates the perfect space between a song-closing guitar blast and the screaming riff that opens the next. After four months of recording and mixing, Soundgarden’s new album “Badmotorfinger” — a pivotal record by a band with a shot at all the marbles — is done.

Singer Chris Cornell, sitting cross-legged on the floor, looks up with a forlorn expression and deadpans, “Now what am I gonna do?”

“Go home,” suggests guitarist Kim Thayil.

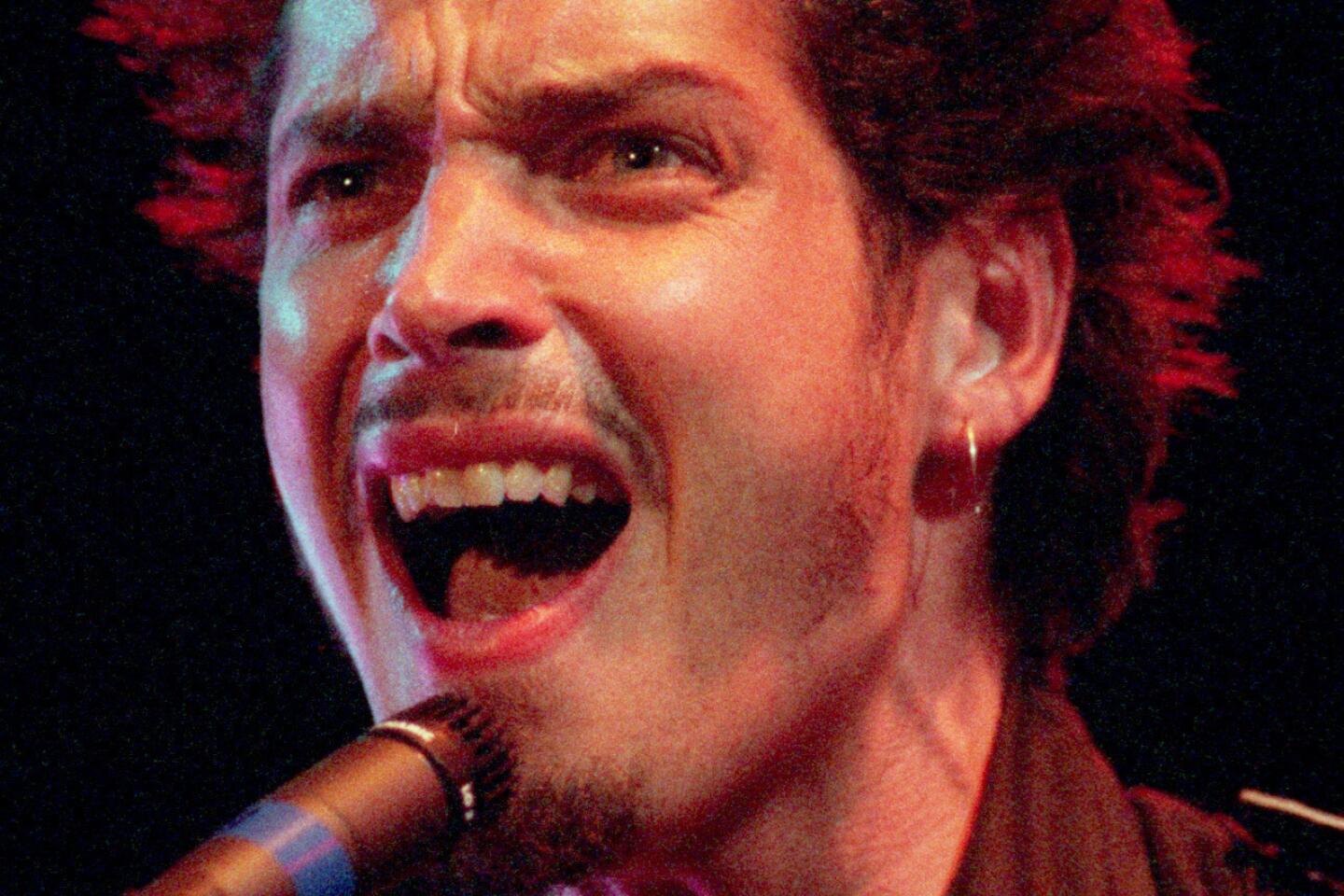

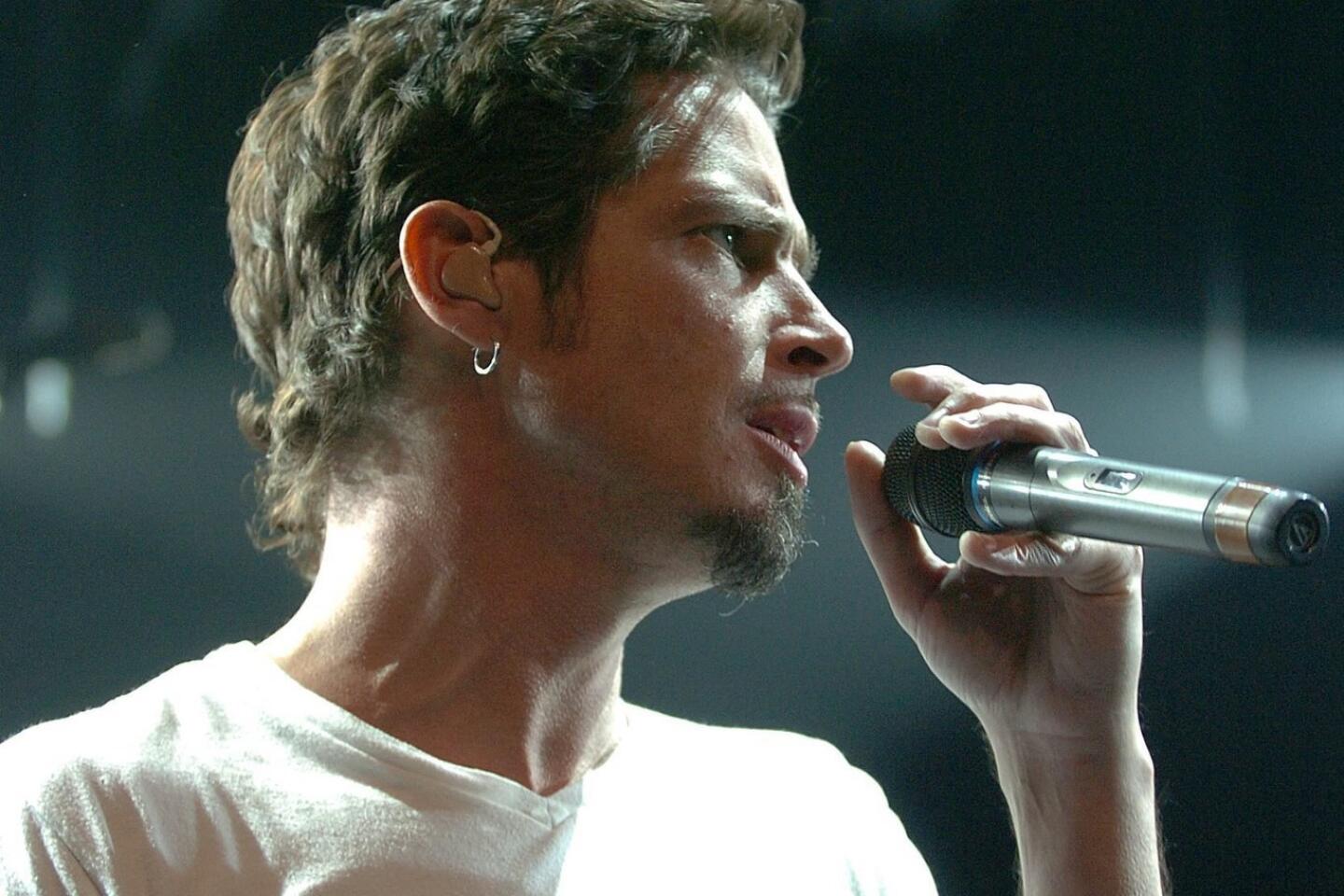

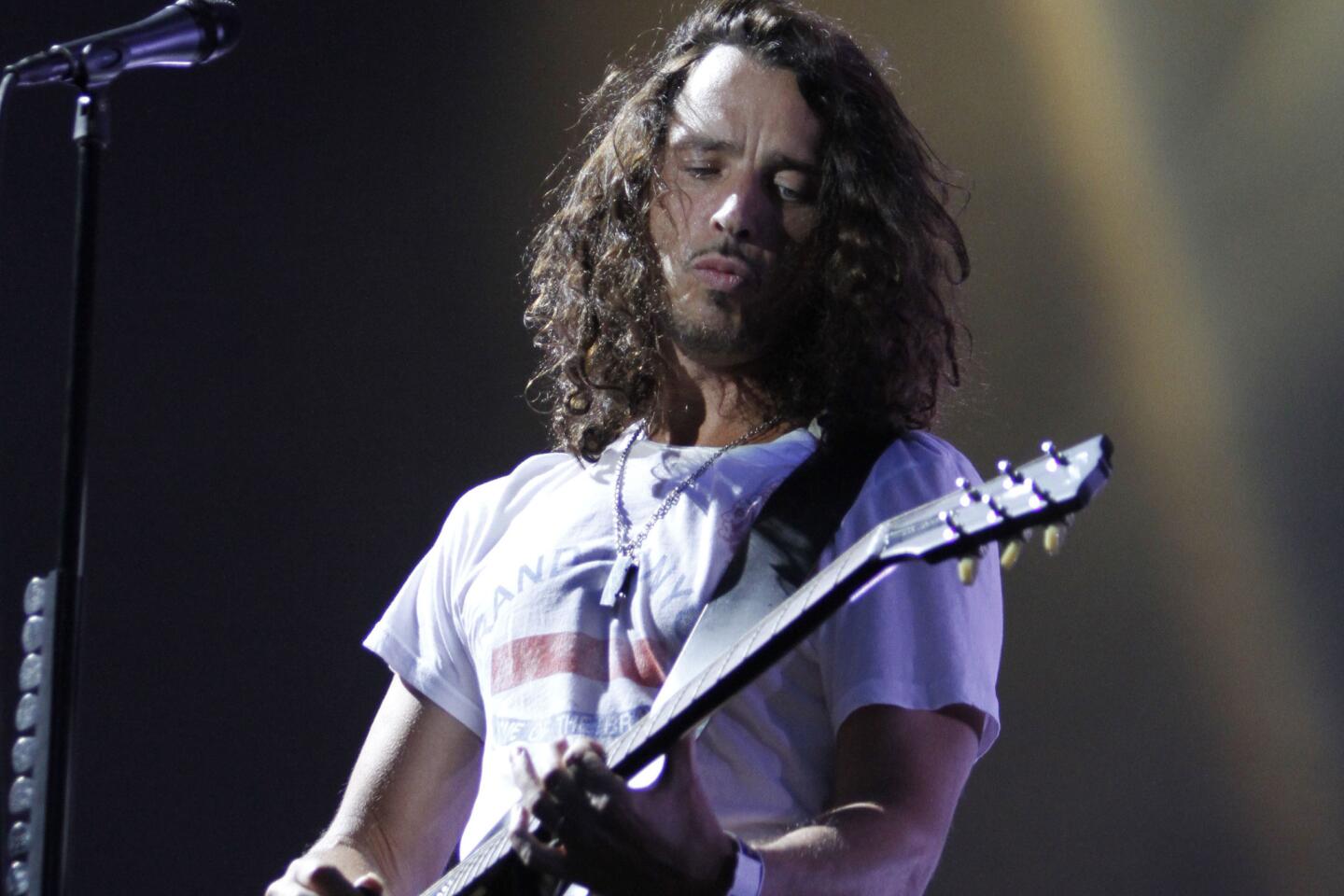

At 6-foot-2, with delicate features and flowing hair, wearing a beret and hoop earrings, Chris Cornell cuts an imposing figure, and he emits a sleepy charisma.

That sounds good to Cornell and the rest of Soundgarden. After two weeks of mixing the album, the four musicians are eager to vacate their apartments in a dead corner of the San Fernando Valley and return to their hometown of Seattle, where the band formed in 1984 and prospered in a vibrant, grass-roots rock scene.

With its charismatic singer and monumental sound, Soundgarden is now poised to ride a unified hard-rock and art-rock audience into the stratosphere. If “Badmotorfinger” clicks when it’s released in late September, Soundgarden could be the band that brings the purifying power of the mighty riff to an alternative-rock audience, and intelligence, experimentation and urgency to metal fans dulled by a parade of peacocks.

“It’s a very emotional kind of music, and that coupled with the heaviness and the hard-rock aspect of it makes it quite special,” says Bryan Huttenhower, director of artists & repertoire at A&M Records, the label that signed Soundgarden in 1988. “I think most bands in that metal genre are not too original these days. There’s not too many bands with a new point of view doing that.

“Their audience goes from the alternative to the metal crowd. They’ve had great success at college radio, they’ve also had success at metal radio. . . . I guess it might be similar to Faith No More and bands like that. Metallica has a lot of credibility in both areas. I think their path is going to be similar.”

There was a real sort of dark, heavy quality to their performances

— Jonathan Poneman, Sub Pop Records

Later, guitarist Thayil pops open a tall Budweiser in a kitchen area of the studio and ponders the question: What are Soundgarden’s goals and rewards?

“Well,” he says as the new album blasts from the speakers in the nearby control room, “hopefully we’ll get to sell more records and play louder.”

At 6-foot-2, with delicate features and flowing hair, wearing a beret and hoop earrings, Chris Cornell cuts an imposing figure, and he emits a sleepy charisma even in a dark coffee shop in Sherman Oaks. Sipping a mineral water, he dismisses the notion that the closely watched Soundgarden is under the gun.

“Eventually (A&M) is gonna expect us to sell records, but I don’t really feel any pressure at this point,” he says. “I’m satisfied with the idea that every time we release a record it sells more and we have more and more people coming to our shows. . . .

“Unanimously we’d like to see ourselves be a multiplatinum band. But to do it any other way than how we do it would be so destructive that we wouldn’t even be able to function as a band. . . . We’re sort of bound to the way that we operate, the way that we function and the way that we work creatively.”

The Soundgarden way involves what Cornel calls an “organic,” slow-growth philosophy (they released a series of records on independent labels rather than sign immediately with a major), rejection of rock-god pretensions, and rigorous control of the band’s music and image.

We’d like to see ourselves be a multiplatinum band. But to do it any other way than how we do it would be so destructive ...

“They’re very focused in what they’re about and how they want to be presented, and they’re pretty hands-on as far as everything from ad copy to artwork,” says A&M’s Huttenhower. “They’ve really created this whole thing for themselves.”

Cornell elaborates: “I think the collective sound and the collective attitude that comes out of the band is what people respond to the most. . . . I don’t think a band should compromise themselves for anything. Not for an audience, not for a record label. Because I don’t think a fan is gonna believe in what you do.

“Fans invest a lot into groups they choose to be fans of. . . . It’s identifying with somebody, which can be a real powerful thing in somebody’s life. The feeling that you’re true to yourself translates almost every time to your audience. That’s the main point that rings true for us and keeps it inspiring and keeps fans inspired. I’m definitely proud of that.”

Cornell, 27, grew up in a middle-class neighborhood just outside Seattle, and had his first taste of rock music when he heard the Beatles’ “Hey Jude.”

“It made me feel like I hadn’t felt before,” he says. “Sort of a strange euphoria. I remember having the single. I was probably 6 or 7. . . . Rifling through my neighbor’s older brother’s records was a common thing, and listening to Lynyrd Skynyrd and Alice Cooper and the Beatles.

“I remember stealing a stack of Beatles records from my neighbors’ basement. They had thrown them on the ground and the basement flooded and all the sleeves were warped. And I took out all the records and put them in between paper towels and brought them home and started listening to them. I sat in my room for weeks on end listening to these records.

“There was no decisive moment when I thought, ‘Wow, I want to do this.’ That wasn’t there at all. It just made me feel good.”

Cornell took piano lessons and later turned to the drums, playing along to records by progressive bands like Yes and Rush as he grew up in rock ‘n’ roll suburbia.

“My neighbors--everyone in my neighborhood had boys for some reason,” he recalls. “So there was plenty of rock and plenty of drugs and stolen cars and everything. Anything you wanted to be bad was as close as your neighbor’s older brother.”

Cornell stayed out of serious trouble, and after undergoing his punk-rock baptism he met Kim Thayil and bassist Hiro Yamamoto in 1984. When they formed Soundgarden, Cornell was the singer and drummer, but he soon moved out front and Matt Cameron joined on drums. (Bassist Ben Shepherd joined the group in April, 1990, following Yamamoto and Jason Everman in that role).

Soundgarden immediately stood out from the pack on the Seattle scene.

“There was a real sort of dark, heavy quality to their performances,” recalls Jonathan Poneman, then a local promoter and now co-owner of Seattle’s influential Sub Pop label.

“Chris always had a very confrontational stage thing happening. It was unique in a lot of ways, because he did not calculate at all. The guy seemed so naive. . . . For one thing he was incredibly young; for two, it wasn’t really considered hip or relevant to be aping Jim Morrison or Iggy in this situation. So it was pretty revolutionary.”

“We were eclectic in our songwriting style,” says Thayil, who has spent much of his time in interviews deriding the perception that Soundgarden is a Led Zeppelin clone. “In general, the trippiness and quirkiness and the humor and the acid qualities were best expressed when we made it heavy.

“There’s nothing like metal parody mixed in with homage, as well as a few trippy hypnotic things that bash you over the head and really draw you in, as opposed to the jangly sort of college pop. That can be trippy, but it’s more sublime when it’s huge and engulfs you.”

Cameron cites AC/DC’s “Back in Black” and Black Sabbath’s “Paranoid” as timeless models. “It’s not a conscious thing where we try to sound like a certain style or a certain record,” the drummer says. “We all were influenced by music that was heavy and had a real bone-crushing, low-end quality to it.”

Soundgarden came to A&M’s attention when Seattle’s public-radio station KCMU sent the company a compilation tape of unsigned bands. Intrigued by Soundgarden’s entry, Huttenhower headed north and caught a show.

“I had never seen anything quite like it before,” he remembers. “They were very heavy, but in a melodic way. . . . And Chris’ vocals were spectacular. It was like a sledgehammer. It hit you right over the head.”

If I didn’t do what I do, I think for the most part I would have very few friends and be a shut-in most of the time.

— Chris Cornell

A&M financed some demos and helped support the group even while it was releasing independent records, first on Sub Pop, then on L.A.-based SST. Soundgarden suddenly became a hot item on the national touring circuit, and a record-company bidding war heated up. “We just hung in there,” Huttenhower says, “and when the dust settled we ended up with the band.”

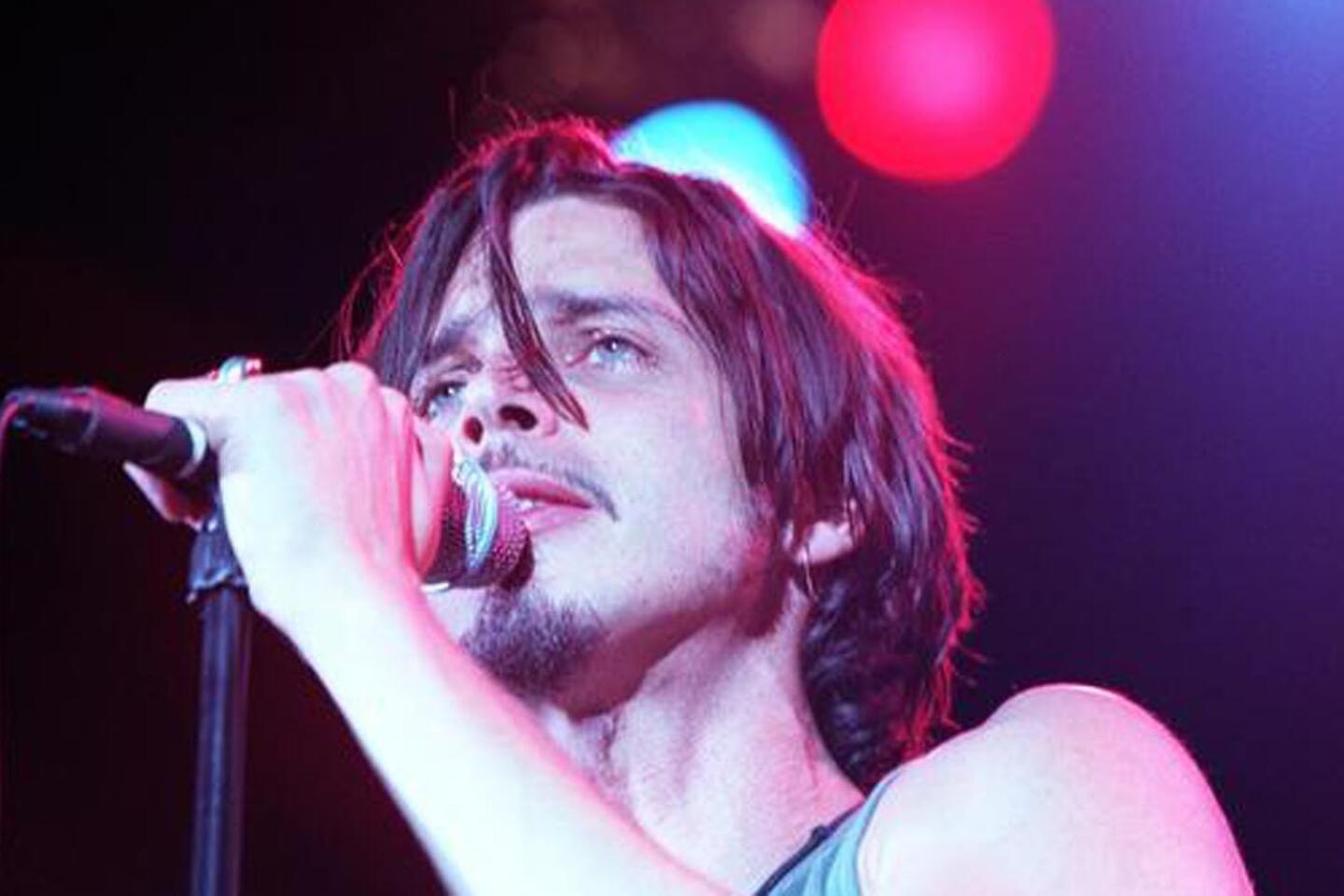

Last year’s major-label debut, “Louder Than Love,” sold a modest 160,000, but established Soundgarden with a wider audience and offered Cornell--lean, bare-chested, head shrouded in curly hair--as a new-metal icon.

“ ‘The quintessential angry young man,’ I got that a lot,” the singer says of that album-cover image.

“I wouldn’t dispute that. There isn’t a day that goes by that I’m not really angry. . . . It’s usually (about) my own lack of ability to accept things or to deal with things or change things. . . . I tend to react to things angrily first. I guess it stems from being impatient.”

Still, Cornell, who has been married for almost a year to Soundgarden’s manager Susan Silver, is more comfortable holing up than manning the barricades.

“If I didn’t do what I do, I think for the most part I would have very few friends and be a shut-in most of the time,” he says. “It’s sort of a battle between that person and then the guy that wants to just let it all out in front of 2,000 people and rant and scream and say anything he wants.”

Says Sub Pop’s Poneman, “I think he’s very much the same guy that he was back then, but, you know, people grow and change, especially given the conditions of their professional ascendancy. He’s been adjusted to the spotlight in a lot of ways.

“Chris is a pretty sensitive guy. . . . People perceive it as a lot of rock star-ism going on there, but he’s just become a much more involved singer over the years. He’s always been pretty quiet and pretty to himself in general. . . . I think people hold him in very, very high regard. . . . His reputation is sterling.”

Cornell’s individual stock rose last April with the release of “Temple of the Dog,” an album in which he teamed with the members of the Seattle band Mother Love Bone. A tribute to Love Bone’s singer Andrew Wood, who died of a drug overdose, the album showcased Cornell’s formidable singing and songwriting in a more conventional, blues-rock context.

Despite that step outside the fold, his bandmates aren’t worried that their frontman will take the attention to heart and drift away.

“People outside the band looking in might get that impression,” says drummer Cameron. “But we still feel like a pretty tight unit. Everyone contributes, he doesn’t really dictate anything and it still feels like a band. . . . He’s definitely a team player.”

For tips, records, snapshots and stories on Los Angeles music culture, follow Randall Roberts on Twitter and Instagram: @liledit. Email: [email protected].

ALSO:

Grunge icon Chris Cornell’s death ruled a suicide

Chris Cornell contributed some of his best work to movies such as ‘Singles’ and ‘Casino Royale’

With Chris Cornell’s death, a generation lost its Robert Plant

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.