In today’s divisive political climate pop artists are shaping the new sound of protest music

One of the most effective protest songs of 2018 doesn’t mention Donald Trump by name.

It doesn’t push back directly against one of his controversial policies, nor does it question the means by which he was elected president. It doesn’t refer to government at all, really, unless you count an image of Uncle Sam kissing a man.

The song is “Americans,” the final track on Janelle Monáe’s album “Dirty Computer,” and what it does is argue that the promise of this country is still something to get excited about — and still something to fight for.

A year and a half into a presidency viewed by many as the most alienating in decades, the sound of resistance has as much to do with inclusion as with strict opposition. It’s about opening arms rather than folding them — an idea of yes more than a firm stance of no.

The genius of “Americans” is in its irresistibility. A propulsive neo-new-wave jam overlaid with stately church organ, the tune draws the listener into Monáe’s vision; it seduces even as it confronts.

“Love me for who I am,” sings Monáe, a 32-year-old black woman from Kansas City, Kan., who says she identifies as pansexual. For her, the American dream is one of acceptance, of not having to adapt to someone else’s specifications in order to live.

That dream once radiated outward, a beacon for people from less open-minded places. But Monáe describes the dream in the context of an internal struggle: “Don’t try to take my country,” she warns, coming as close as she ever does to naming Trump (and his followers), “I will defend my land.”

Remember who we used to be, the song demands — or who we used to believe we were.

“I’m not crazy, baby,” Monáe assures us, “I’m American.”

It’s far from the only protest song to deploy that method at a moment when the battle for hearts and minds is happening here at home.

The music — by acts like Monáe, Beyoncé, Luis Fonsi and Childish Gambino (who echoes Monáe’s language in his viral hit “This Is America”) — is slick, even commercially minded in a way we haven’t always associated with protest art; it rarely makes embracing a progressive cause — be it the loosening of traditional gender roles, the struggle against police violence or the recognition of those pushed to the margins of American life — feel like a chore.

COMPLETE COVERAGE: The new sounds of protest

And why would it? Trump swept to power as an experienced entertainer using his natural charisma to sell a radical message that some, at least, would have been unlikely to buy from someone less skilled.

“I’m not crazy, baby. I’m American.”

— Janelle Monáe

For all the criticism he’s earned for demonizing certain groups, the president’s real talent might be the way he makes his supporters feel seen.

So, of course, those in the resistance are equally determined to establish a sense of community. And of course they’re relying on the flash and exuberance of great pop to do it.

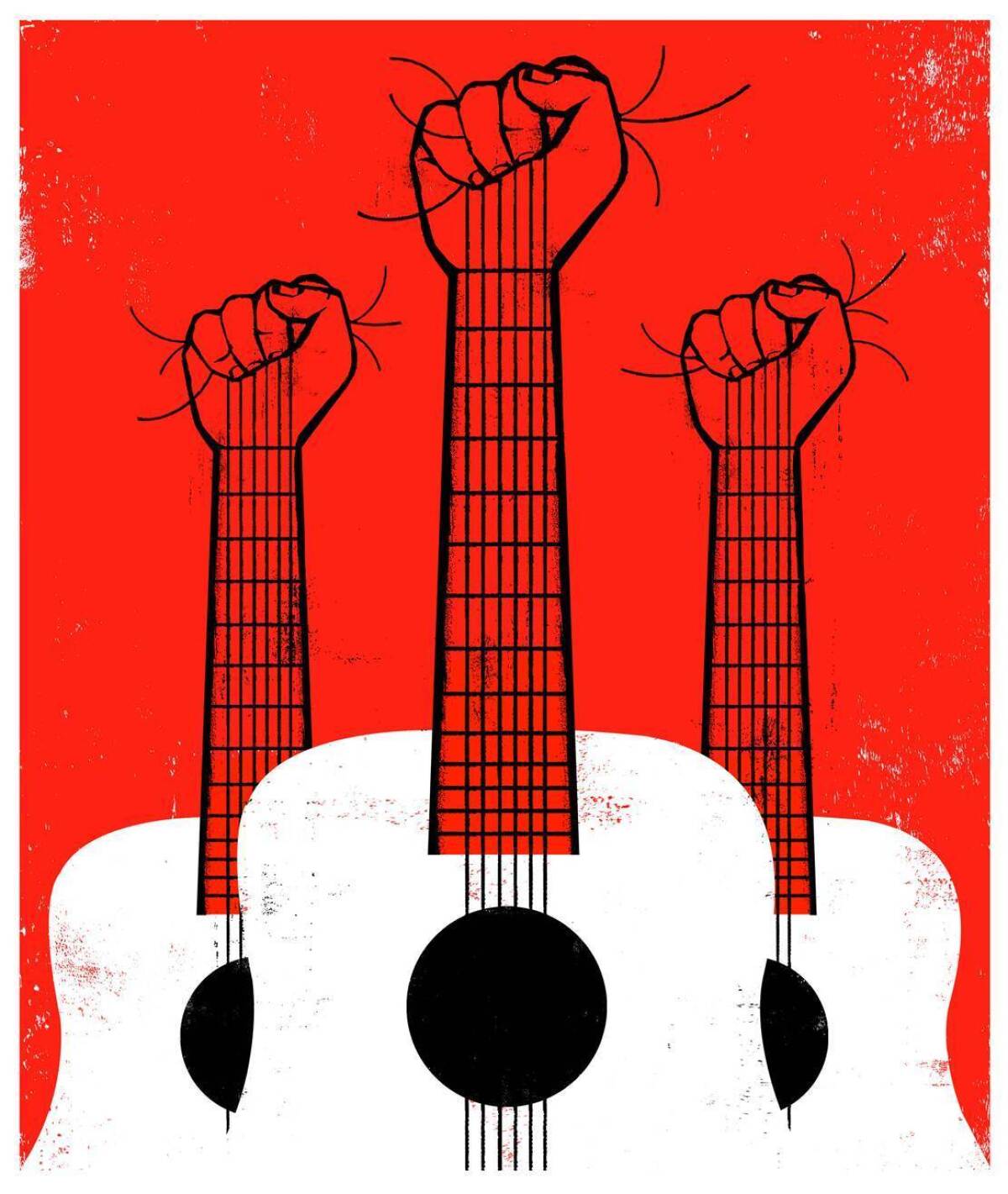

That represents a shift from some previous eras, in which protest music often took a harder, more rough-edged form — think of the weedy-voiced folkies of the 1960s or the shouty hardcore bands of the 1980s. For those artists, finesse was something to strip away in an effort to uncover (and to project) real truth.

And it’s still seen that way by some. Last fall Eminem made waves with a raw, unaccompanied rap called “The Storm” in which he laid into Trump with his voice as his only tool.

Fiona Apple created a similarly primal chant, inspired by the president’s “Access Hollywood” boast about groping women, for the 2017 Women’s March in Washington: “We don’t want your tiny hands / Anywhere near our underpants.”

But songs increasingly are utilizing catchy melodies and danceable grooves to imagine a better, more equitable world — or to present this world in the kind of positive light that Trump seems willfully to withhold.

Listen to the loving recognition of Spanish-speaking people in Fonsi and Daddy Yankee’s “Despacito,” which spent 16 weeks at No. 1 amid the president’s fearmongering about immigration. Do the same with “Havana” by Camila Cabello, who recently told me that her success with the slinky bilingual love song is her “rebellion-slash-protest against the anti-immigrant sentiment that’s going on.”

“All of a sudden, it’s not this outlier,” she said of Latin music in the U.S. “It’s just normal.”

Perhaps the most powerful example of this resistance-through-representation is Beyoncé and Jay-Z’s new “Everything Is Love” album, which the superstar couple released without notice a few weeks ago. As on her “Lemonade” and his “4:44,” the record ponders a marital crisis against the backdrop of their status as two of the most famous (and richest) musicians on earth.

By proudly emphasizing their blackness, though — as in a music video for one unprintably titled track that has them posing next to the largely white images that fill the Louvre — Beyoncé and Jay-Z are also making space for the consideration of African American achievement.

They’re inviting others to see themselves in their success, and making that only easier to do with the aesthetic allure of a song like the warmly sensual “Heard About Us.”

Heed the last word in that title, which so many protest musicians have used as a mere rhetorical position from which to attack “them.”

Yet Beyoncé and Jay-Z don’t bother much with drawing an enemy. They know who they’re up against, and so does the listener.

For these un-crazy Americans (to use Monáe’s phrase), the thing worth exploring is “us.”

ALSO

Kamasi Washington’s ‘Heaven and Earth’ proves jazz’s vitality and political power

Beyond outrage: Australia’s Stella Donnelly mixes the personal and political with humor

To Hurray for the Riff Raff’s Alynda Segarra, the personal is political

‘I can’t stay completely silent’: Jason Isbell looks inward in examining a ‘White Man’s World’

California Sounds: L.A. artists rage and wrestle with politics and policy in the age of Trump

Twitter: @mikaelwood

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.