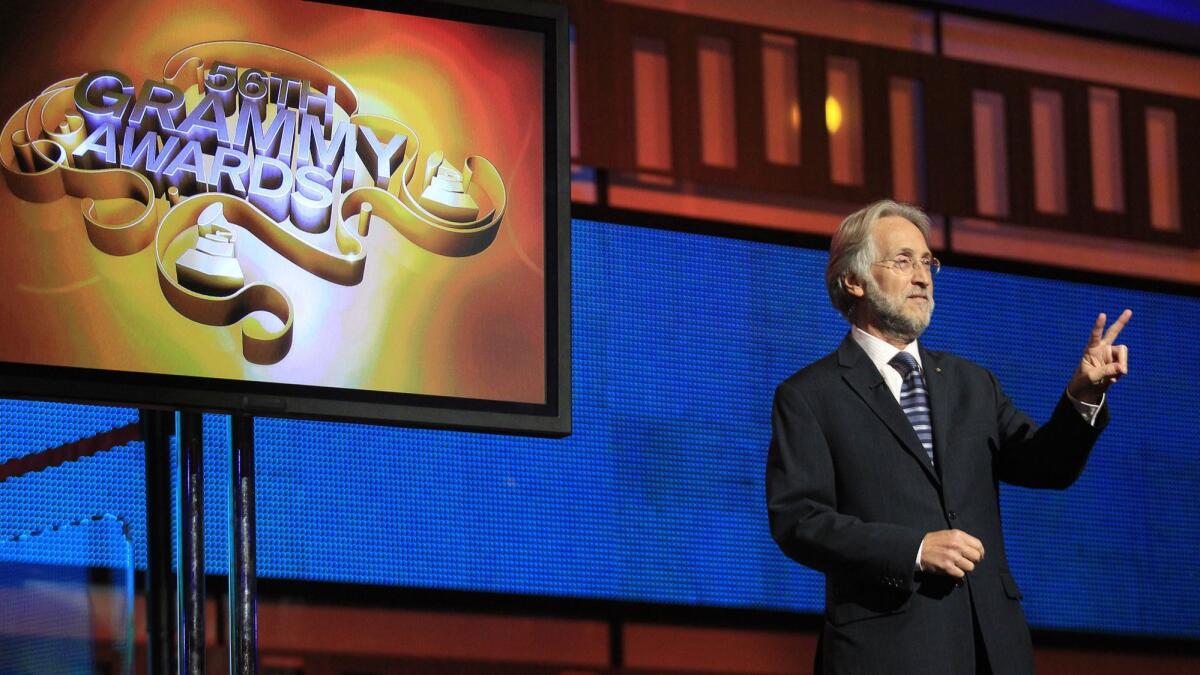

Recording Academy chief Neil Portnow preps for his swan song Grammy Awards ceremony

Neil Portnow set a number of goals for himself and the Recording Academy when he was hired nearly 17 years ago to take over the reins, including expanding general awareness of the organization beyond the one night a year it puts on the national telecast of the Grammy Awards.

He also stored away the idea of creating a smooth transition at whatever point he would eventually leave his post.

The best-laid plans?

That might have turned out to be the case had he not spoken what he now refers to as “those two words,” a reference to his post-Grammy Awards show response to a question about last year’s male-centric results and telecast.

That’s when he said that the time had come for women to “step up” to receive their due, unleashing a firestorm of criticism on social media and elsewhere, with many calling for Portnow to step down. About four months later the academy announced that he would do just that, but not until his current contract expires at the end of July — almost 18 months after the “step up” remark.

Today his choice of words, for which he issued a quick apology a year ago, still makes him grimace.

“There seemed to be a natural desire to conflate that with my determination about when it was time to move on,” Portnow said. “The fact is, there’s no relationship between that whatsoever.

“Frankly, had there been any other objective, the board of any organization would not keep a CEO in place for a year if they had any doubts or reservations or concerns about that individual’s character, service and effectiveness.”

Portnow is just the third paid, full-time president in the history of the organization, which had relied in its first three decades on volunteer music industry executives to steer the ship. During his tenure Portnow expanded the organization’s reach, rebuilt its charitable arm MusiCares, championed key federal legislation and refined the awards process, at one point overseeing the reduction of more than 30 categories in an effort to fine-tune and revitalize the ceremony.

Portnow followed C. Michael Greene, whose 14-year tenure ended with his abrupt resignation, without public explanation but amid sexual harassment allegations — a moment of leadership crisis for the academy.

“That was a difficult transition,” Portnow, 71, said during an interview last week at his Santa Monica office, which is densely decorated with guitars, gear, photos, artwork and other music-related ephemera he’s amassed over the years. “When that happened, one thing I said to myself and ultimately to the board, was that when the time comes for the next transition, one of my goals is that it be a smooth one, because we’ve never had one.

“It’s the best way to run a business, to have that figured out and not have to be in a crisis,” said the man who came to the job as a musician and indie label record executive with a reputation as a consensus-builder and peacemaker.

Plenty of attention will be placed on whom the Recording Academy chooses as a successor. Following the outcry last year from female and male musicians and other record industry representatives, the academy announced in May it would assemble a task force to explore biases — conscious or unconscious — working against women, people of color or the LGBTQ community receiving equal consideration in the Grammy Awards nomination and final vote process.

Former First Lady Michelle Obama’s ex-chief of staff Tina Tchen was brought in to oversee the task force, which quickly moved to alter the makeup of some of the key committees that help determine the nominees and award recipients.

They also reached out with efforts to recruit more than 900 new members to add to the academy’s existing membership rolls of nearly 25,000 industry professions, students and adjunct members. About 200 accepted in time to take part in the awards that will be announced Sunday during the prime-time CBS broadcast.

Last week the academy also unveiled a new initiative aimed at bringing parity to one facet of the music business still overwhelmingly dominated by males: record production and engineering. A USC Annenberg study leading into the 2018 Grammy ceremony showed that just 2% of producers and 3% of engineers and mixers are female.

Portnow hopes that recent moves to address that imbalance will be an important part of the legacy he leaves behind.

Whoever gets the awards, to me it’s all about balance and doing the right thing.

— Neil Portnow

“Whoever gets the awards, to me it’s all about balance and doing the right thing,” Portnow said. “There are always going to be different agendas for different groups of people and constituencies. Being a kid in the ’60s, social justice is something I grew up with.

“Growing up with a consciousness about that, coming from a family that was very socially responsible … I know firsthand what kind of passion and dedication is required for any social change, and sometimes to get there you have to put the blinders on and just focus on what the agenda is and what needs to change, so I applaud that.

“In our case, what we absolutely must ensure and which everyone has worked very hard on, is that every element of the process is fair,” he said.

As a start toward addressing the gender imbalance in the world of producers and engineers, the academy will establish a web page dedicated to identifying female producers, engineers and mixers and is lobbying those in positions of hiring to consider qualified female candidates before making their final decisions.

“I just got a copy of this task force [report] on diversity and inclusion and really trying to expand the opportunities for female producers and engineers,” said veteran music mogul Clive Davis. “It is very admirable, very worthwhile and very special.”

The “step up” controversy was easily the biggest hurdle Portnow has encountered during 16-plus years as president and CEO.

“I believe any missteps, perceived or otherwise attributed to Neil, should also be measured against his successes, his commitment and loyalty,” Nashville-based record producer and then-chairman of the academy’s board Garth Fundis told The Times this week, nearly a decade and a half after he presided over the move to remove Greene and hire Portnow.

Portnow didn’t specify what his post-Recording Academy life will entail. All he said about his decision not to seek a contract renewal was that after almost 17 years, the time felt right to move on.

“It just worked that way, which is, on a personal level, a little bit unfortunate because after 40 years in the business without incident and without any kind of controversy, as a human being that’s never comfortable,” he said.

Under Portnow, the value of the academy’s assets has more than tripled to $170.4 million now, according to an academy spokesperson.

While Greene negotiated a more lucrative contract with CBS for the broadcast rights, pushed for the creation of a Grammy Museum and led the establishment of the Latin Grammys, those are three key initiatives that Portnow has continued or expanded on his watch.

When Portnow took over in November 2002, he had much to mop up.

The academy’s board agreed to a $650,000 settlement in 2001 with a former human resources official who threatened to sue over claims that Greene sexually assaulted and harassed her. An internal investigation cleared Greene.

In 1998, New York City’s then-Mayor Rudy Giuliani banned the Grammys from being held in Manhattan after Greene allegedly threatened the life of one of Giuliani’s deputies over show negotiations. Portnow persuaded the city officials to let the ceremony return in 2004 for its 45th anniversary, and the show was held there again last year on the 60th.

When Greene suddenly resigned in April 2002, he was kept on as a consultant during the transition that culminated in the hiring of Portnow six months later.

“Neil Portnow was the right choice at the right time,” Fundis said. “The organization was in need of a fresh approach and we felt an immediate and much-needed embrace from many in the music industry as a result of our hiring Neil. But his commitment to the Recording Academy began many years before he became its president,” referring to Portnow’s track record of volunteer service for nearly a decade before he was hired.

Portnow moved quickly to mend fences with veteran impresario Dick Clark, who had filed a $10-million lawsuit against the Recording Academy after Greene banned musicians from appearing both on the Grammy Awards and Clark’s rival American Music Awards telecasts.

Portnow also delivered on the academy’s long-simmering wish to establish a facility touting its legacy, one that was realized with the 2008 opening of the Grammy Museum at L.A. Live, part of a relationship Portnow nurtured with developer AEG, which built Staples Center, the Microsoft Theater and the surrounding complex of retail and dining establishments that also includes the three-story/four-story Grammy Museum.

Among the other accomplishments Portnow speaks about with pride is the growth of the MusiCares philanthropic wing that provides multi-pronged aid to musicians in need. And the annual Person of the Year fundraiser, which began in 1991, expanded under Portnow’s watch into a signature event that has generated upward of $6 million to $7 million each year during an evening that has paid tribute to musicians including Aretha Franklin, Paul McCartney, Bruce Springsteen, Barbra Streisand, Stevie Wonder, Elton John, Tom Petty, Carole King and Bob Dylan leading into this year’s salute on Friday to Dolly Parton.

In fact, Portnow included a stop Monday at the Grammy Museum to visit with Parton and stump on behalf of MusiCares at the opening of a new exhibit of Parton’s flamboyant fashion sense that will run through March 17.

The growth of MusiCares, which provoked controversy during Greene’s time with the academy for the way it administered funds, has been one of Portnow’s greatest sources of pride. Popular philanthropic rating site Charity Navigator gives MusiCares its highest possible rating of four stars.

“I’m very proud of MusiCares and where we’ve gone with something wonderful and a great concert [annually] and just taking it and expanding it really making it a priority,” Portnow said. “That might be the end goal for me: that anybody who puts their hand up for help, we’re able to be there for them.”

Portnow also has been directly involved with the creation and recent passage of the Music Modernization Act, a bill that won rare bipartisan support in the Senate and House of Representatives and was signed into law in October by President Trump. The measure addresses various outdated laws governing the way music publishing and other royalties are calculated, collected and paid to music creators, and was hailed in many quarters in the music business when it passed.

“That’s become one of the leading agendas for the academy,” Portnow said. “When we survey our members every so often, advocacy and MusiCares come back as the top areas of interest to members, and what they think is important, what resonates with them and why they want to belong.”

Building the Recording Academy’s influence beyond Grammy night is another area Portnow has focused on. It’s manifested in the additional music specials the academy helps assemble as part of its ongoing contract with CBS and in conjunction with Ken Ehrlich AEG Ventures, longtime producer of the Grammy telecast.

That initiative has yielded more than two dozen music specials in recent years in addition to the Grammy broadcast, both for CBS and elsewhere, such as shows highlighting special merit and lifetime achievement award winners, as well as a string of “In Performance at the White House” programs during President Obama’s administration that were co-organized by the Grammy Museum.

“It was part of my agenda to take the most recognized brand of music, which I always thought was fairly underrepresented, and have it be everything it deserved to be,” Portnow said, suggesting he thought it was long past time for the Recording Academy itself to step up.

“It’s really time for us to celebrate and recognize how important what we do is,” he said, noting that he has not given a lot of thought to what he’ll do after July, in that it’s all-hands-on-deck time at academy offices through Grammy night and beyond. “We’ve got the best platform on the planet to do it. So let’s do as much as we can.”

Follow @RandyLewis2 on Twitter.com

For Classic Rock coverage, join us on Facebook

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.