Rolling down Rosecrans in Compton, L.A. hip-hop’s Main Street

Like Sunset Boulevard and rock or Beale Street and the blues, Compton’s Rosecrans Avenue — described in song by producer-rapper DJ Quik as “a long-ass avenue that goes from the beach to the streets” — conjures a musical essence beyond the pavement itself.

If Compton is the heart of L.A. hip-hop, Rosecrans is its pulse.

Rosecrans has played a role as an incubator for essential L.A. rappers such as Kendrick Lamar, Dr. Dre, YG, the Game, DJ Quik, Problem and dozens more. Since N.W.A’s 1988 album “Straight Outta Compton,” artists have long used the 27-mile-long avenue as a backdrop.

Yet whereas songs about Sunset Boulevard have tended to romanticize the sun-drenched Southern California ideal, those set 15 miles south on Rosecrans have been riddled with violence, a truth that frustrates attempts to reframe Compton’s image.

The Age of Hip-Hop

From the streets to cultural dominance

The 2018 Grammy nominations are overdue acknowledgment that hip-hop has shaped music and culture worldwide for decades. In this ongoing series, we track its rise and future.

You won’t hear lyrics about the city’s birth as the flood-prone midpoint between downtown Los Angeles and the L.A. harbor, or about how in the 1940s a huge migration of African Americans transformed South Los Angeles.

“Who blew up that McDonald’s on Rosecrans and Central, dude,” wonders King Tee in his 1987 track with Mixmaster Spade and the Compton Posse, “Ya Better Bring a Gun,” which is the first known rap song to utter the avenue by name. The McDonald’s is still there — right across from Tam’s Burgers at Rosecrans and Central avenues.

"This is where I seen my second murder, actually," Lamar told Rolling Stone at Tam’s Burgers in 2015. "Eight years old, walking home from McNair Elementary. Dude was in the drive-thru ordering his food, and homey ran up, boom boom — smoked him."

Rosecrans in the age of hip-hop has come to symbolize that which unites and divides its residents, the pathway that leads to and from salvation, a River Styx where both temptation and redemption lurk.

“Every spot in Compton got something going on, but Rosecrans is the common denominator,” says the 32-year-old Problem. “There’s a lot to talk about, there’s a lot to live about, there’s a lot to say, there’s a lot to represent.”

‘You gotta zoom’

On a recent Friday afternoon the Compton-raised rapper Problem was riding in the passenger side of a late-model BMW convertible as it tentatively exited the Tam’s Burgers parking lot.

“You gotta zoom,” Problem, born Jason Martin, urgently says to the driver. “You see the tempo around here?”

In the same Tam’s lot that Problem just left, jailed rap kingpin Marion “Suge” Knight is accused of striking two men with his truck, during an incident allegedly involving his portrayal in the N.W.A biopic “Straight Outta Compton.” One of the men died.

Nominated for a Grammy for his role in co-writing rapper Rapsody’s track “Sassy,” Problem has walked the Rosecrans tightrope his whole life, so he understands how to navigate West Coast rap’s most famous avenue.

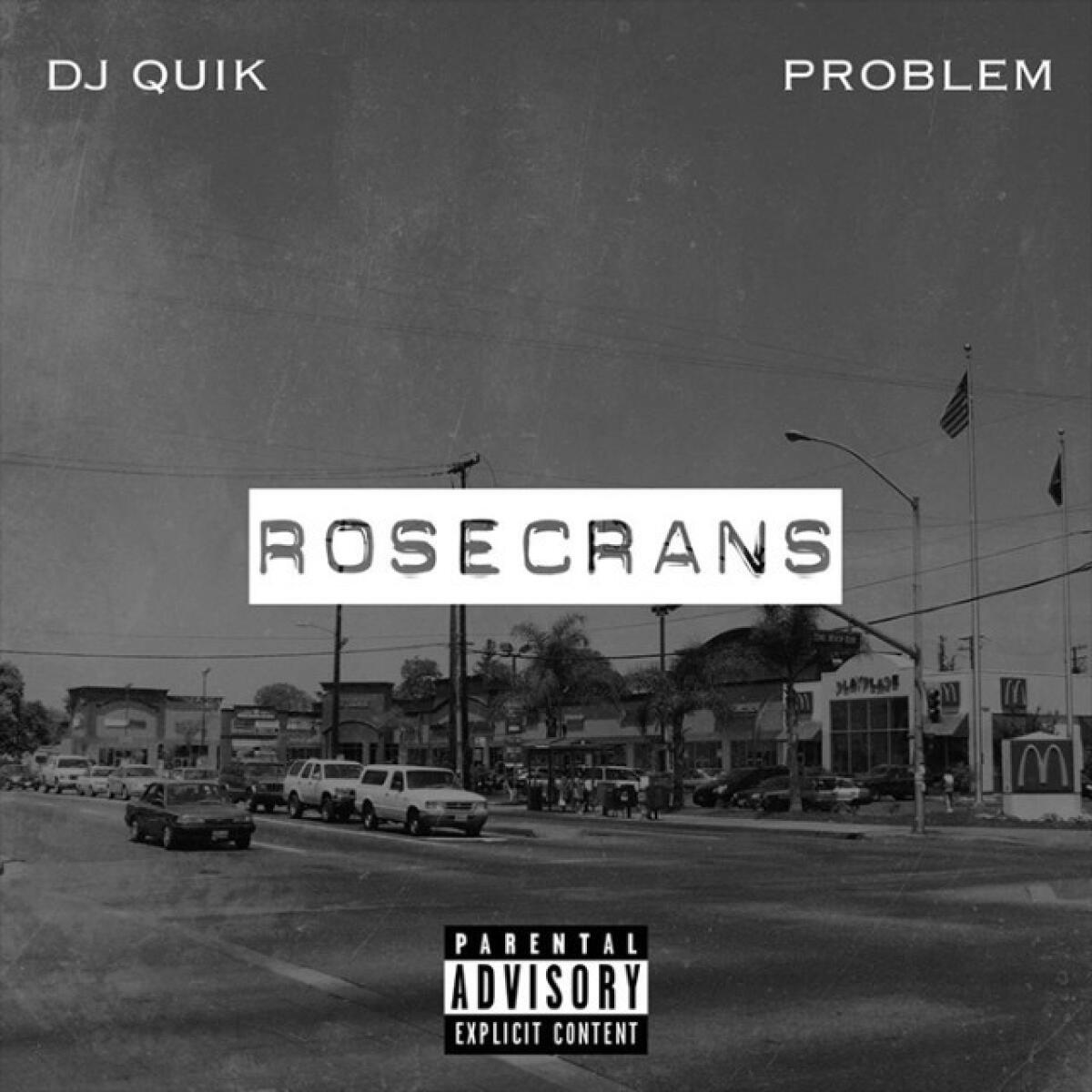

Problem last year teamed with Quik for an entire album dedicated to it. Called simply “Rosecrans,” it’s a love letter to a rough-and-tumble road whose boundaries — visible and invisible — have connected and separated its citizenry.

Beginning at its eastern end at North Euclid in Fullerton, the avenue runs westbound through Norwalk, Clearwater, Compton, Gardena and Hawthorne before ending south of LAX in Manhattan Beach. Along the way, a few rusty-but-working wells pump oil, remnants of a time less than a century ago when this land was a vast, but ultimately untenable, oil field.

Across its expanse through South Los Angeles, Rosecrans now serves as home to hundreds of small businesses, Oxman’s Surplus, Canary World Exotic Bird Farm, Salon de Leon, King Palace Buffet, Mr. Rosewood Restaurant, Donut King, Express Pawn Shop and Paramount Campers among them.

As anyone who’s heard West Coast rap in the past three decades knows, at its midpoint Rosecrans passes through the heart of gangland L.A., serving as a boundary that divides turf among various gangs.

“When I'm riding down Rosecrans you never know what you can see,” sings Candice Boyd during the hook for DJ Quik and Problem’s “Rosecrans” title track. “R.I.P. while you riding down Rosecrans.”

“I'm on Rosecrans ... at Tam's Burgers — I'm buying AKs and handguns,” raps YG on “Bompton,” describing his aim to “do the enemies foul.”

“Come and visit the tire-screeching, ambulance, policeman / Won't you spend a weekend on Rosecrans,” raps Lamar on “Compton,” a breakout track from his 2012 album, “good kid, m.A.A.d. city,” describing the “khaki creasing, crime increasing on Rosecrans.”

A measure of Rosecrans’ potency? One of Compton’s most famous contemporary musicians, YG, tends to steer clear of the avenue these days. In 2015, the rapper was shot outside his North Hollywood studio, and the perpetrator has never been found. Citing “concerns for his safety,” the rapper declined to be interviewed or photographed on Rosecrans (he ultimately canceled a scheduled phone interview).

That hasn’t stopped him from documenting Compton’s main artery: “And I ride the main line, up and down Rosecrans I'm gonna shine,” he raps on “G$FB,” a track that transposes images of him celebrating on the avenue with others of him threatening prostitutes and boasting of his pimping.

‘A different type of thinker’

Yet it’s perhaps no wonder the city’s contemporary music documents turf wars, gun play and hometown pride.

Why Compton? The traits are in its DNA.

Compton in the 1940s and ’50s was a mostly white suburban enclave, says Tyree Boyd-Pates, history curator and program manager at the California African American Museum. At the time, the city’s enforcers were what he describes as “white gangs that terrorized blacks and Latinos” and “very similar to what black people were leaving the South with the KKK.”

As Compton integrated — a shift exacerbated by the 1965 Watts uprising — what evolved in the 1970s and ’80s, says Boyd-Pates, was “the hyper-criminalization of those African Americans” by the justice system. One byproduct of this power struggle was an emboldened community whose voices were eager to vent in rhymed couplets.

Growing up inside this system, Boyd-Pates continues, “allowed for the Dr. Dres and the Eazy-Es who were coming up in that age to solidify their identity as the messengers of the streets. And they were able to embody and encapsulate what it meant to be a black male.”

“You gotta understand,” Problem says as the BMW moves eastbound on Rosecrans, “the mentality of someone that lives here has to be different than when you live other places, just from the history of it. And it breeds a different type of thinker.”

Despite all the lyrical gunplay and criminality depicted in music about Compton, says Boyd-Pates, the city remains “a really important place for black Angelenos, because it is the one place where they’ve felt that they've gotten an opportunity to fulfill the American dream.”

He adds, “It’s a really amazing city that doesn't get its due because of the negative portrayals that followed it for the last 20 years.”

When Problem and Quik decided to expand their 2016 release “Rosecrans EP” into an album, says Problem, the ideas flowed.

“It just sparked up so many conversations and different experiences he had on certain parts of Rosecrans, and the ones I’ve had, and the ones we’ve had together,” Problem said. (DJ Quik declined to be interviewed.)

The album’s title track captures the breadth of the avenue’s allure, beginning with singer Boyd’s confession that she’s cruising with the windows rolled up because she and her companions are smoking weed “as we’re riding down Rosecrans.”

Rapper the Game offers a specific location to where he and his compadres Big Fase, Frog Dog, Bad Ass and Chuck are headed: “Dippin' down the ’Crans, right on Wilmington, right on Brazil.”

Rappers aren’t the only artists to have focused on Rosecrans. The first known song to reference it, in fact, was Los Angeles chronicler Jimmy Webb with his “Rosecrans Boulevard.”

Best known for his cake-in-the-rain ode to “MacArthur Park” 12 miles away, in 1967 Webb offered his song to the pop band the Fifth Dimension. Though it’s an avenue, Webb turns it into a boulevard for a tale about a hotel tryst with a stewardess.

In the intervening half-century, Rosecrans evolved. Today, Webb and his stewardess may have opted for an Airbnb in Venice.

“Everywhere changes,” Problem says. “The look of it, yeah, the feel of it. It’s going to always be different from the generations prior.”

ALSO

For tips, records, snapshots and stories on Los Angeles music culture, follow Randall Roberts on Twitter and Instagram: @liledit. Email: [email protected].

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.