How the Grammys became cool (and what the Oscars can learn)

Kendrick Lamar has been nominated 11 times for “To Pimp a Butterfly,” one shy of the record for one album set by Michael Jackson’s for “Thriller” in 1984.

It feels odd to congratulate an awards ceremony that is already an exercise in self-congratulation. It’s a bit like saying, “Thank you for cashing the check I sent you!”

But the 58th Grammy Awards deserve applause, no matter which musicians take home Grammys on Monday night. The Grammys stand out by comparison with their cinematic sibling, the Oscars. The #OscarsSoWhite controversy revealed an academy so out of touch it was practically crying out for an intervention.

The Grammys are in touch, mostly.

FULL COVERAGE: Grammy Awards 2016

The major nominees this year are popular, respected and involved in the work of writing, and updating, the language of popular music.

Kendrick Lamar has been nominated 11 times for “To Pimp a Butterfly,” one shy of the record for one album set by Michael Jackson’s for “Thriller” in 1984. That makes sense. I grew up watching light rock acts like Christopher Cross beat Aerosmith and waiting for the Recording Academy to realize rap not only existed but also was important.

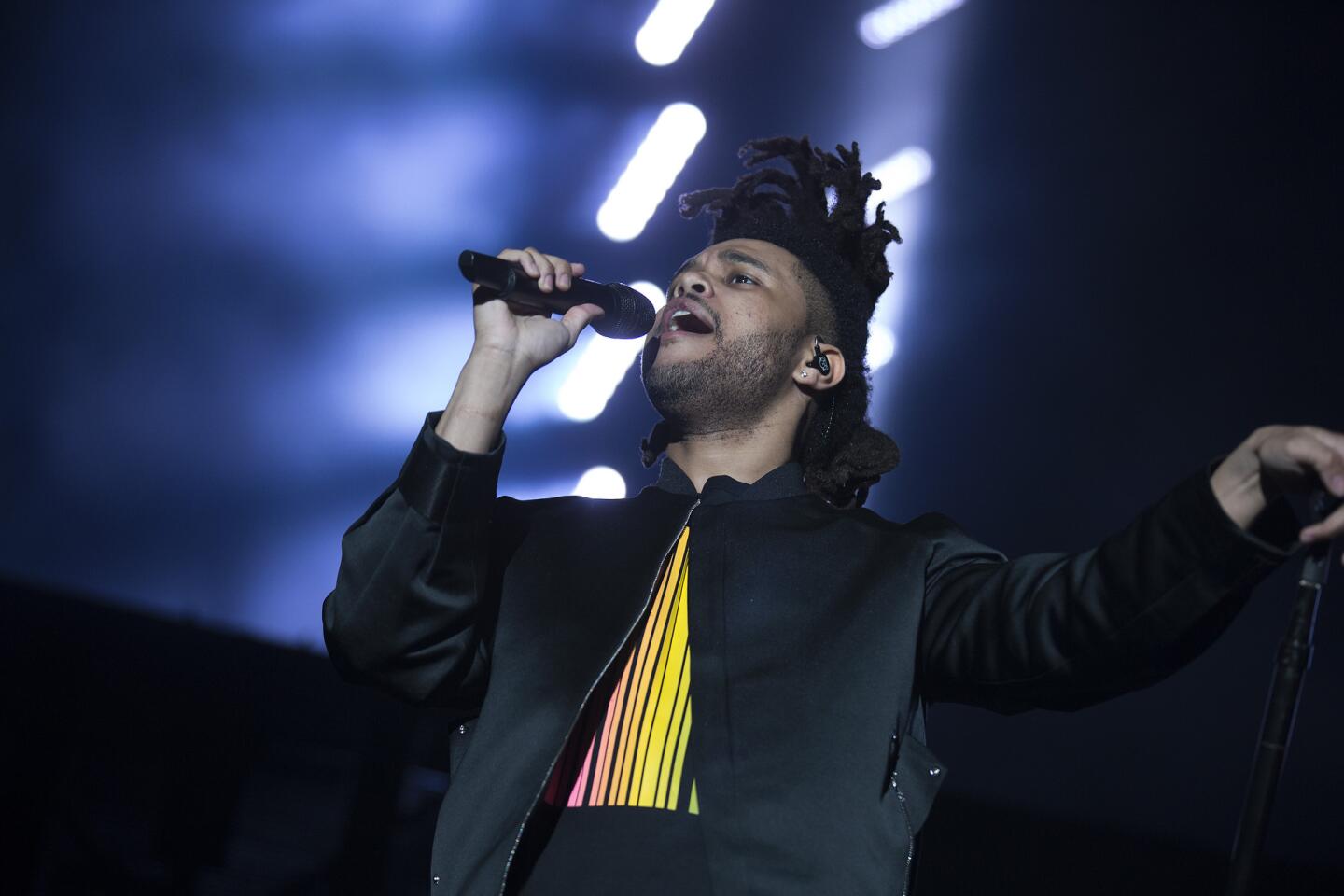

Now the worst thing that could happen Monday night is that the Weeknd wins album of the year. Would that be bad because I don’t love the album? No, all five nominees for album of the year, as in most categories, are good and relevant, and that’s the point. The Grammys would have to do something really odd to screw this one up.

Since 2012, artists have been winning Grammys while they are having an influence. That year, an overhaul streamlined the categories with consumer tastes in mind. No longer do we have Herbie Hancock winning album of the year for a set of Joni Mitchell covers. “River: The Joni Letters” from 2008 is an intermittently inspired album, especially when Hancock’s piano is channeling Mitchell’s melodies, but it was not the album of 2008 in any popular, critical or spiritual way.

More to the point, it suffered the age-old Oscars problem, in musical terms. Instead of winning for something as uncanny and unprecedented as 1976’s “Taxi Driver,” Martin Scorsese had to wait 30 years to win the best picture Oscar in 2006 for “The Departed,” a capable genre movie.

In 1961, a 21-year-old Hancock appeared on Donald Byrd’s taut “Free Form,” which did not win album of the year or any other Grammy. That year, Bob Newhart’s “The Button-Down Mind of Bob Newhart” won album of the year. (It’s on Spotify, if you’re curious.)

Neither Mitchell’s “Hejira” and “Blue” won album of the year when they were eligible, nor did Hancock’s classic ‘60s albums “Maiden Voyage” or “Speak Like a Child” win any Grammys.

The 2008 awards — Hancock also won for contemporary jazz album — felt like an apology to Mitchell and Hancock and baffling to the rest of us. One has to assume that the win by “River” was a ballot bottleneck, with votes being split among too many overly specific categories, sort of a Ralph Nader moment for the Grammys.

The categories are now easier to understand, but the music business has never been trickier to understand: Blame the new, tortured path from a listen to a royalty.

Popularity, though, is now easier to measure: Thank the easily tracked Web click. These may be major keys to understanding why the Grammys have figured out how to host an awards show.

The Los Angeles Times has reported on the alarming demographics of the Oscars voting bloc — more than 90% white with a median age over 60, and able to vote unto death before rule changes just announced.

Popularity is now easier to measure: Thank the easily tracked Web click.

— Sasha Frere-Jones, Los Angeles Times Critic at Large

We know less about the Grammy voters. It is a much larger cohort; with 20,000 people eligible to vote, compared with about 6,300 for the film academy. According to Recording Academy rules, those Grammy voters must be pros with credits on at least six commercially released tracks.

Maybe to vote on the Oscars you can be some random suit, or a guy who walked across the screen once in “Point Break.” But not the Grammys. The voters are people in the act of making records, consistently. A 300-person screening committee then goes through the 20,000 ballots, under the supervision of the Deloitte accounting firm. What comes out the other end? The nominations.

Aside from being an awards ceremony, the Grammys are an old-fashioned spectacle, where set pieces and musical numbers can fill in the blanks missed by nominations. Because every awards fandango has a chronological eligibility bracket, there is always the slightly old material that feels out of place and the obvious absence of something popular — say, Adele’s “25” — that was released right after the cutoff.

This is where performances come in. Rihanna’s “Anti” was just released but is playing pretty much everywhere. Whether it is the best “Anti” it could be — it’s close — it is deeply relevant. So Rihanna will be performing.

The old Recording Academy might have been too confused by the nature of sales nowadays to figure out what to do with Rihanna. One cannot be blamed — here is how “Anti” came out.

On Jan. 27, Samsung sponsored a limited giveaway of “Anti,” which I happened to learn about because I saw a tweet and was awake. (Thank you, Pacific Standard Time.) For reasons I did not entirely understand, I was allowed to download a FLAC version (a high-quality digital format) of “Anti” for no money, as did 1.27 million other people. The free downloads stopped the next day.

On Jan. 29, “Anti” starting being sold through digital retailers, and on Feb. 5, the physical version became available. Back up, though — on Feb. 1, the New York Times questioned “Anti” with this headline: “Rihanna’s ‘Anti’ Sells Fewer Than 1,000 Copies in U.S., but Some Call It a Hit.” The next day, Rihanna’s Instagram account announced “#ANTI is now officially PLATINUM!!!”

So there’s the problem that the music industry and the Grammys are always up against. Is there any way to accurately count music sales anymore? The New York Times reported that those 1 million Samsung downloads had led the Recording Industry Assn. of America to award Rihanna a platinum plaque. This was true. But Nielsen Music did not count those Samsung-sponsored downloads as sales.

Billboard, yet a third organization, now has “Anti” at No. 1 on the album charts, based on what it calls “multi-metric consumption.” This means that Billboard takes into account a combination of digital sales, physical sales and streaming numbers. The result is fairly accurate, in terms of what people are doing with their listening time; that No. 1 on the Billboard 200 makes more sense than Bob Newhart’s 1961 album of the year.

But the math is dizzy across the board. According to Nielsen Music, “Anti” has been credited with 180,000 “total consumption” units. This includes 124,000 album sales, 456,000 individual track sales and 15.6 million on-demand streams (500 streams are equivalent to one album sale, as Nielsen counts it).

In the old days, 180,000 wasn’t halfway to gold status. But maybe the Recording Academy has realized the Old World is old.

What will happen on Monday? Lamar, Taylor Swift and Chris Stapleton will likely divide most of the awards, with Lamar taking home the lion’s share. The rock categories and new artist category look dodgy, and there could be an unfortunate appearance by Seth MacFarlane, “traditional pop vocalist.”

The ghost of Bob Newhart, “recording artist,” haunts the building. But Rihanna can put the ghosts to bed, at least for a year.

ALSO:

Eagles’ Glenn Frey to be saluted by bandmates at Grammy Awards

Adele, Kendrick Lamar, The Weeknd to perform at the Grammys

10 essential artists who helped Kendrick Lamar shape ‘To Pimp a Butterfly’

Grammy Awards to broadcast ‘Hamilton’ opening number live from Broadway

Why B.B. King was a slam dunk for a Grammy tribute

Flying Lotus and L.A.’s experimental music scene are poised to scoop up Grammys

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.