Review: Bon Iver and TU Dance bring ‘Come Through’ to the Hollywood Bowl

In a note sent to photographers ahead of Bon Iver’s performance Sunday night at the Hollywood Bowl, the Grammy-winning band from Wisconsin politely asked that frontman Justin Vernon’s face not be shown in any pictures.

That’s pretty unusual for a group on Bon Iver’s level — and for one so widely perceived as a vehicle for a single creative mastermind.

But it’s par for the course for Vernon, who seems to have spent the decade since his breakout album, “For Emma, Forever Ago,” determined to shake off pop stardom of the conventional type.

Initially released in 2007 on MySpace, before the Jagjaguwar label reissued it the next year, “For Emma, Forever Ago” presented Vernon as an exceptionally sensitive acoustic troubadour; the album’s origin story has the singer writing and recording all by his lonesome in his father’s remote hunting cabin.

His subsequent work, though, has been increasingly defined by collaboration, with side projects in varying styles, including blues and soft rock, and guest appearances on records by everyone from Kanye West to the Blind Boys of Alabama. Later this month he’s set to release an album he made with Aaron Dessner of the National.

Does Vernon’s star power play a role in getting all this stuff done? Of course. (It’s also why the guy might expect photographers to comply with the request about his face.)

But as often as not, he’s demonstrated a striking disregard for personal celebrity as anything beyond a means to an end.

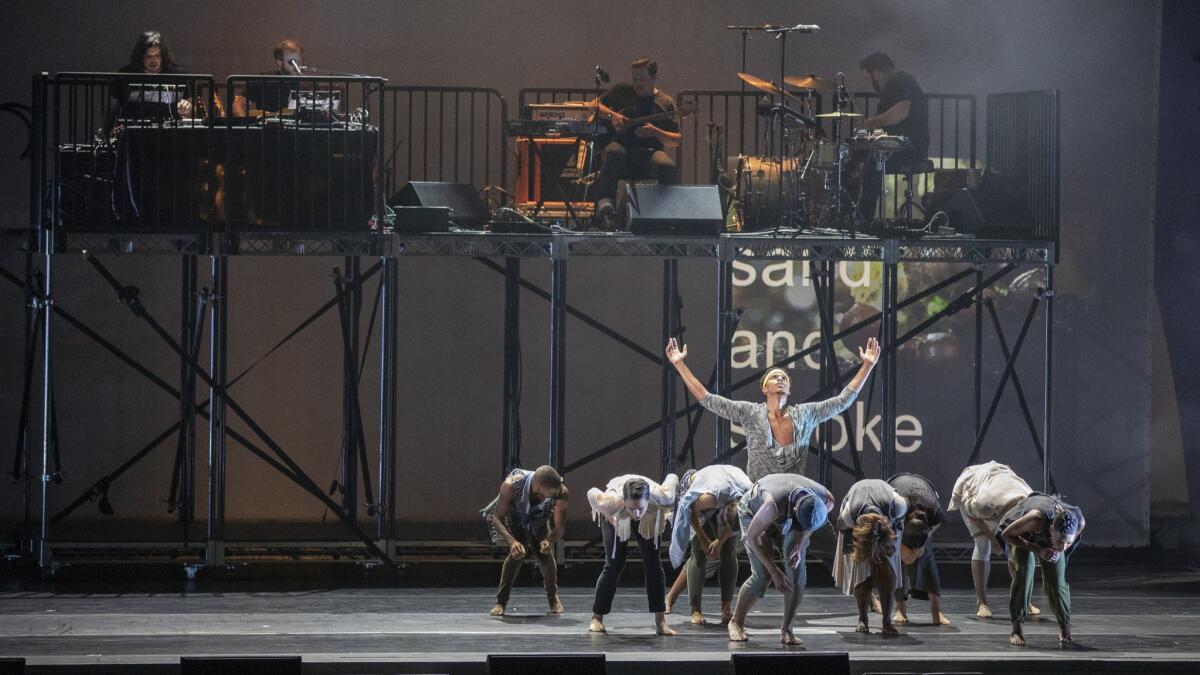

So it went at the Hollywood Bowl, where Bon Iver provided live accompaniment for Minnesota’s TU Dance company in what was billed as the West Coast premiere of a new music-and-dance production titled “Come Through.”

Commissioned by the St. Paul Chamber Orchestra, it’s a 75-minute piece about — well, about a lot of things, as far as I could tell with my shallow understanding of dance.

There were lyrics about love and family, and there was choreography that evoked the idea of people running from (or maybe toward) danger. One sequence featured recorded excerpts from a speech Viola Davis gave at the Women’s March in Los Angeles in January; another had images of a hoodie like the one Trayvon Martin was wearing when he was shot and killed in 2012.

Bon Iver, with Vernon and three other musicians, occupied an elevated platform at the rear of the stage, between the dancers and a large video screen. Most of the time the band was in shadows.

I’d have been interested to find out how many people in the audience knew what they were showing up for — whether they were aware that Vernon had no plans to sing anything, for instance, from Bon Iver’s most recent album, “22, A Million,” which came out in 2016.

Certainly the woman sitting next to me expected Bon Iver’s version of hits — and then appeared bummed out, at least at first, when they didn’t come.

But Vernon’s willingness to risk disappointing his fans is just another facet of his seemingly genuine commitment to art not designed merely to bolster his legend.

That’s not to say the performance, which Vernon has said he hopes to take on tour, was out of step with Bon Iver’s established aesthetic. Much of the music combined Vernon’s electric guitar with the kind of intricately programmed beats he emphasized on “22, A Million.”

His singing, too, showcased his full battery of vocal signatures: his pained growl, his delicate falsetto, his liberal use of Auto-Tune. One song sounded like an old-timey folk ballad as reimagined by Nine Inch Nails; another had a lengthy saxophone solo that made you think about Peter Cetera.

Near the end of the evening, Vernon did a relatively straightforward take on “A Song for You,” Leon Russell’s classic ode that dozens of other artists have covered over the last few decades.

I can’t be sure what Vernon and the members of TU Dance were trying to say in the moment, as a pair of hooded dancers twirled around each other in time to the music. The vision was sensual but laced with anxiety — love in an era of extraordinary rendition, let’s say.

But the choice of material felt instructive: Vernon had taken “A Song for You” from Russell (or perhaps from Donny Hathaway, whose interpretation Vernon came closest to); now he was giving the tune to his collaborators.

It wasn’t about him in the beginning, and it wasn’t about him in the end.

Twitter: @mikaelwood

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.