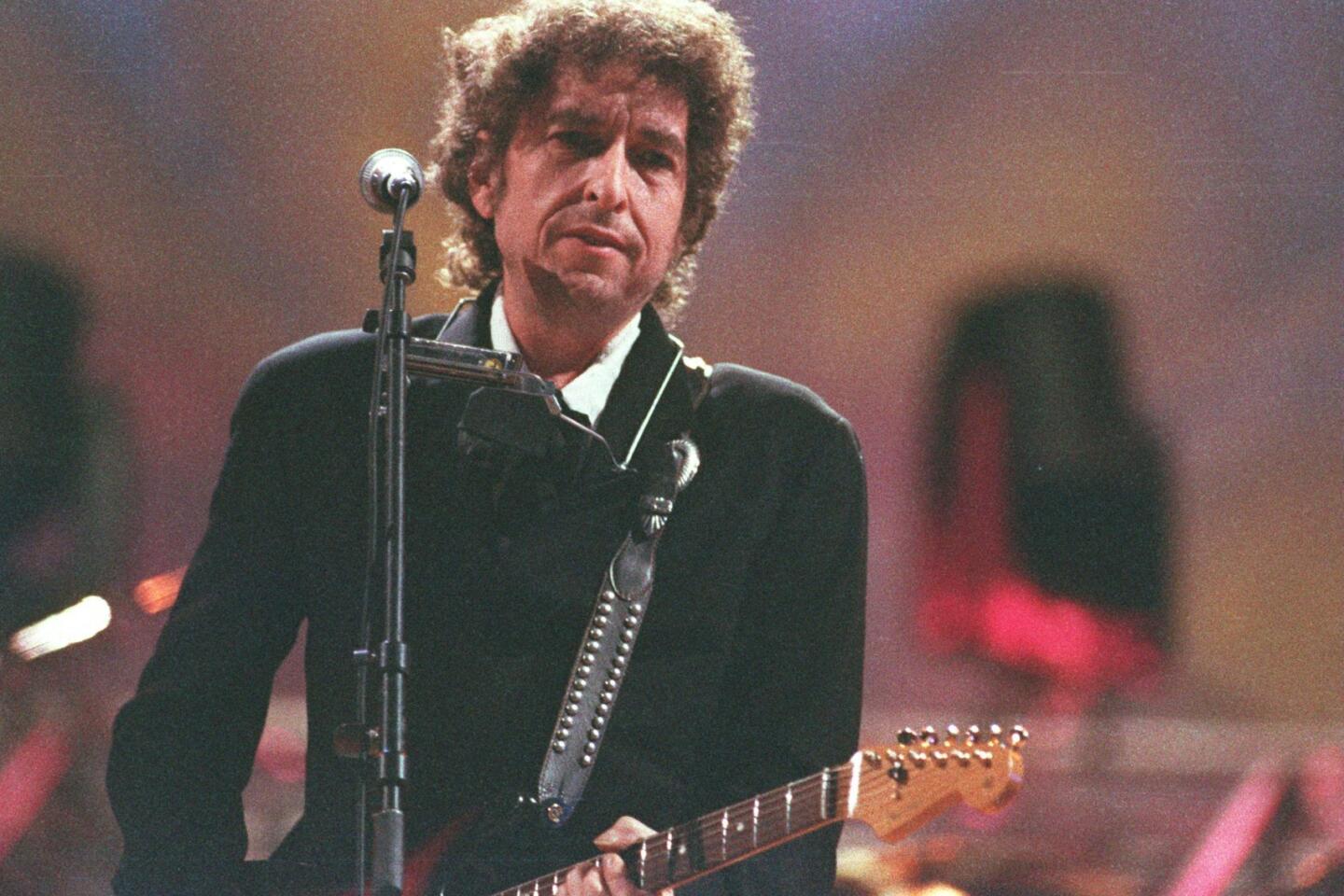

Bob Dylan: ‘The Homer of our time’

Bob Dylan opened the doors of what was possible in popular music with his 1965 single “Like a Rolling Stone,” a 6-minute epic built on four poetically surrealistic verses linked by the emotionally liberating “How does it feel?” chorus.

Then he blew those doors off the hinges the following year with his “Blonde on Blonde” album, which took his literate lyrics into the realm of the epic poets of ancient times.

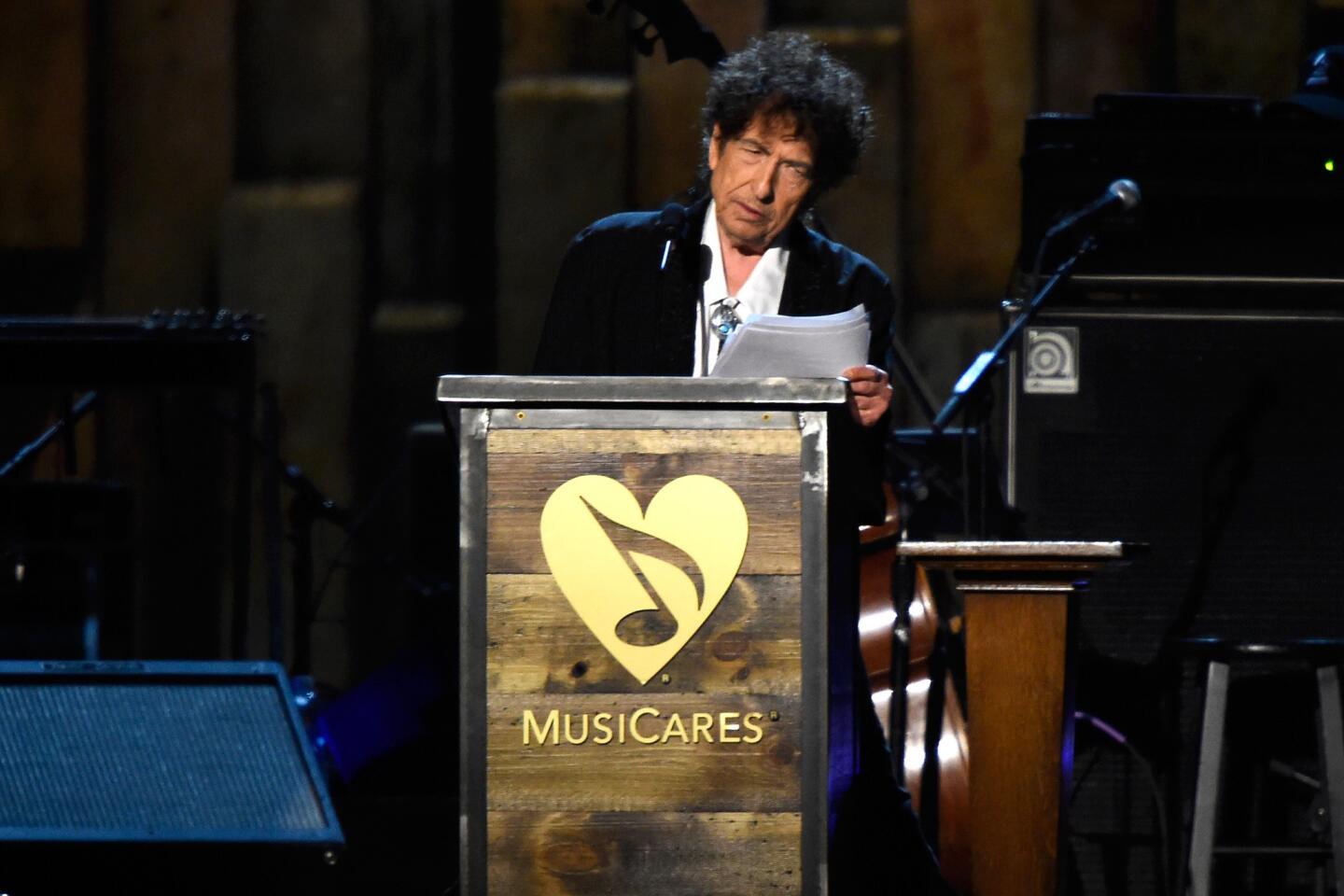

In announcing Dylan as the 2016 recipient of the Nobel Prize for literature, the Swedish Academy’s permanent secretary, Sara Danius, said the selection honors Dylan “for having created new poetic expressions within the American song tradition.” Then she suggested that an interviewer start with his “Blonde on Blonde” to find out what all the fuss was about.

In what was considered a “radical” choice, Bob Dylan was announced as the winner of the Nobel Prize in literature on Oct. 13.

So expansive was what Dylan had to say at this creative peak of the mid-1960s that in “Blonde on Blonde,” he released the first double album by a major pop figure. Album-closer “Sad Eyed Lady of the Lowlands” is an 11-minute, 19-second Hellenic rock music volley that has launched at least a thousand interpretations over the last 50 years.

“With your mercury mouth in the missionary times/And your eyes like smoke and your prayers like rhymes/And your silver cross, and your voice like chimes/Oh, who among them do they think could bury you?” Dylan sings.

That’s just the opening. It continues to overflow with evocative allusions, revealing adjectives and imaginative metaphors, each setting the stage for another question posed to the song’s unidentified subject, often presumed to be Dylan’s first wife, Sara Lownds.

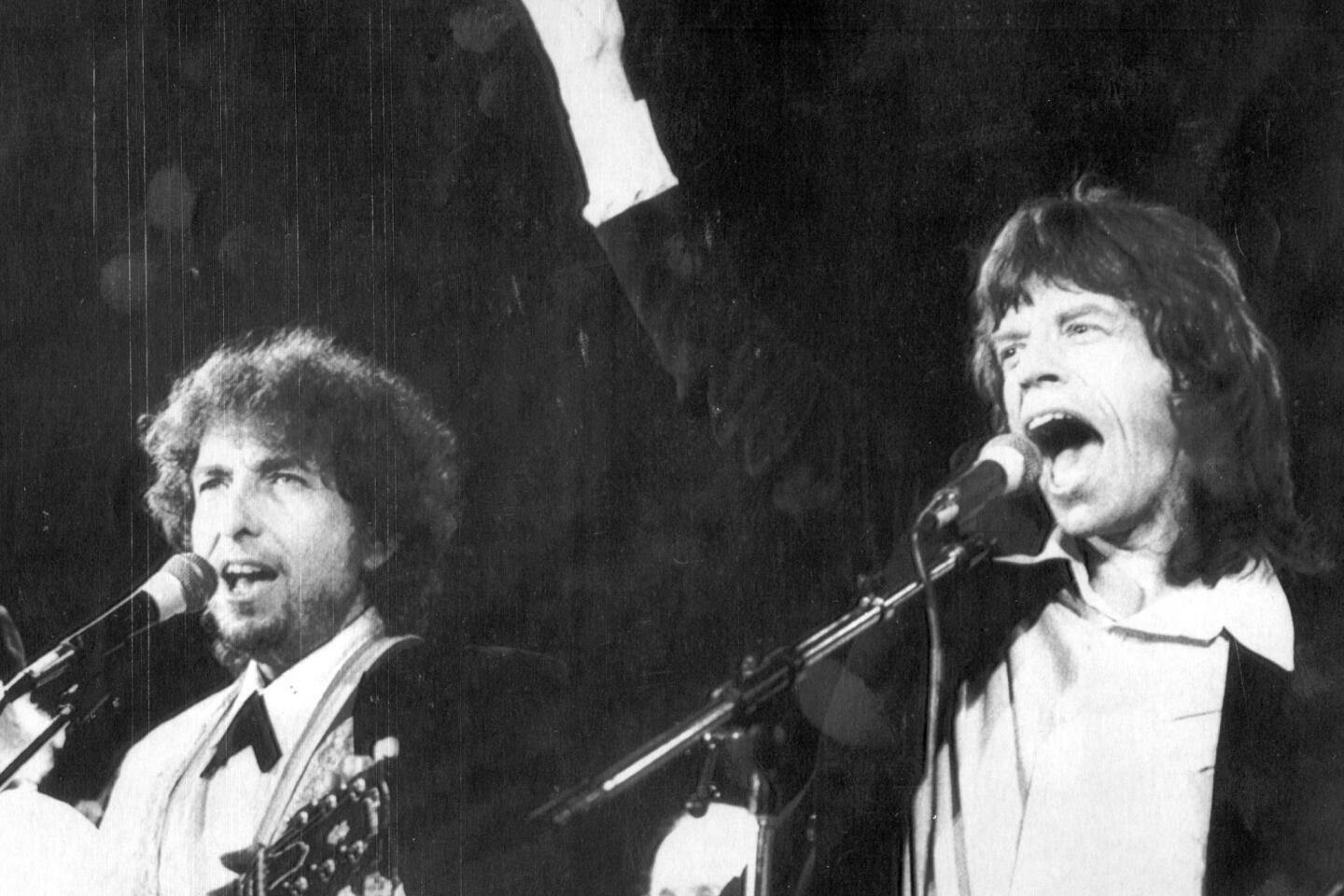

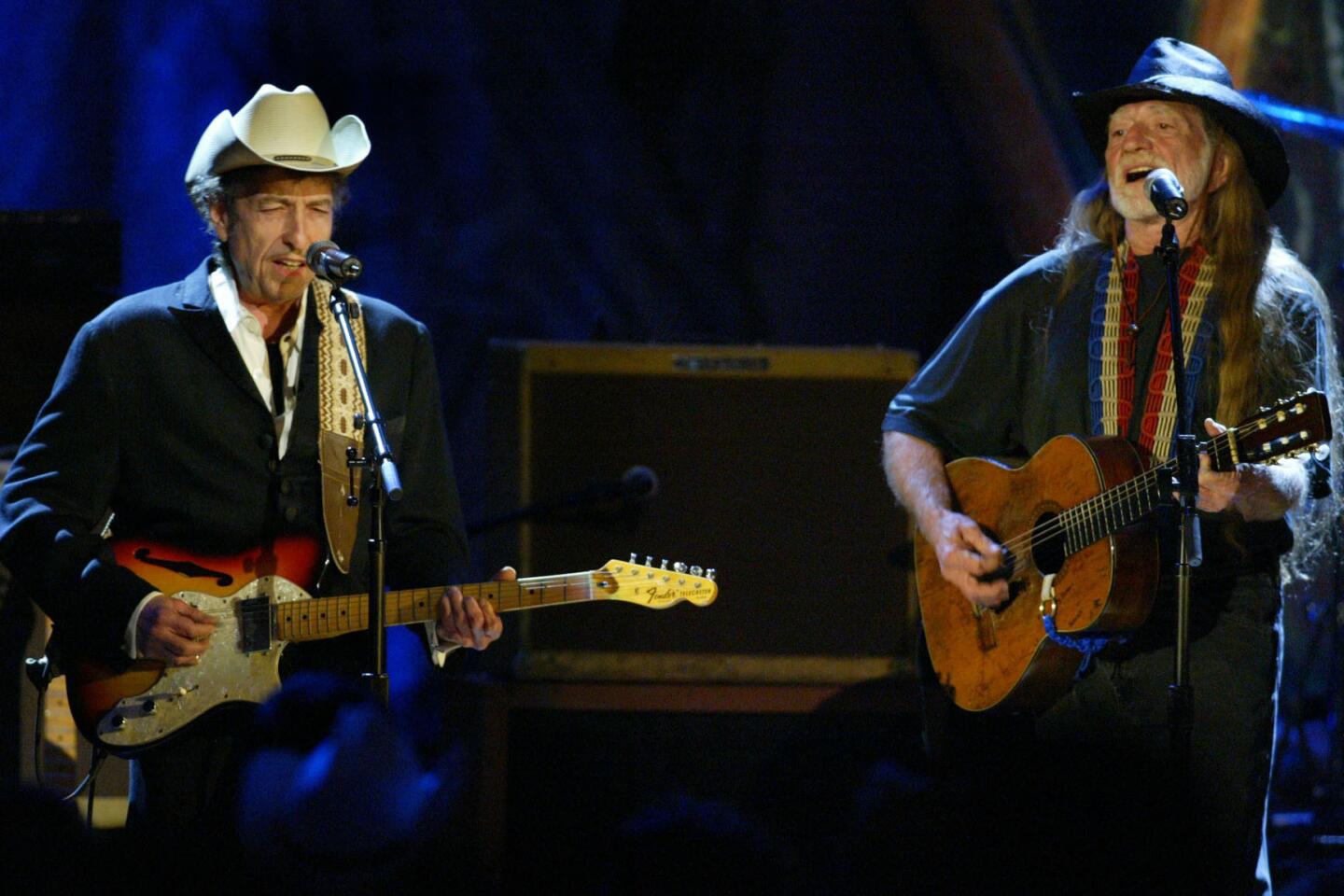

As Bruce Springsteen put it when inducting Dylan into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1988, “Dylan was a revolutionary. The way Elvis freed your body, Bob freed your mind.”

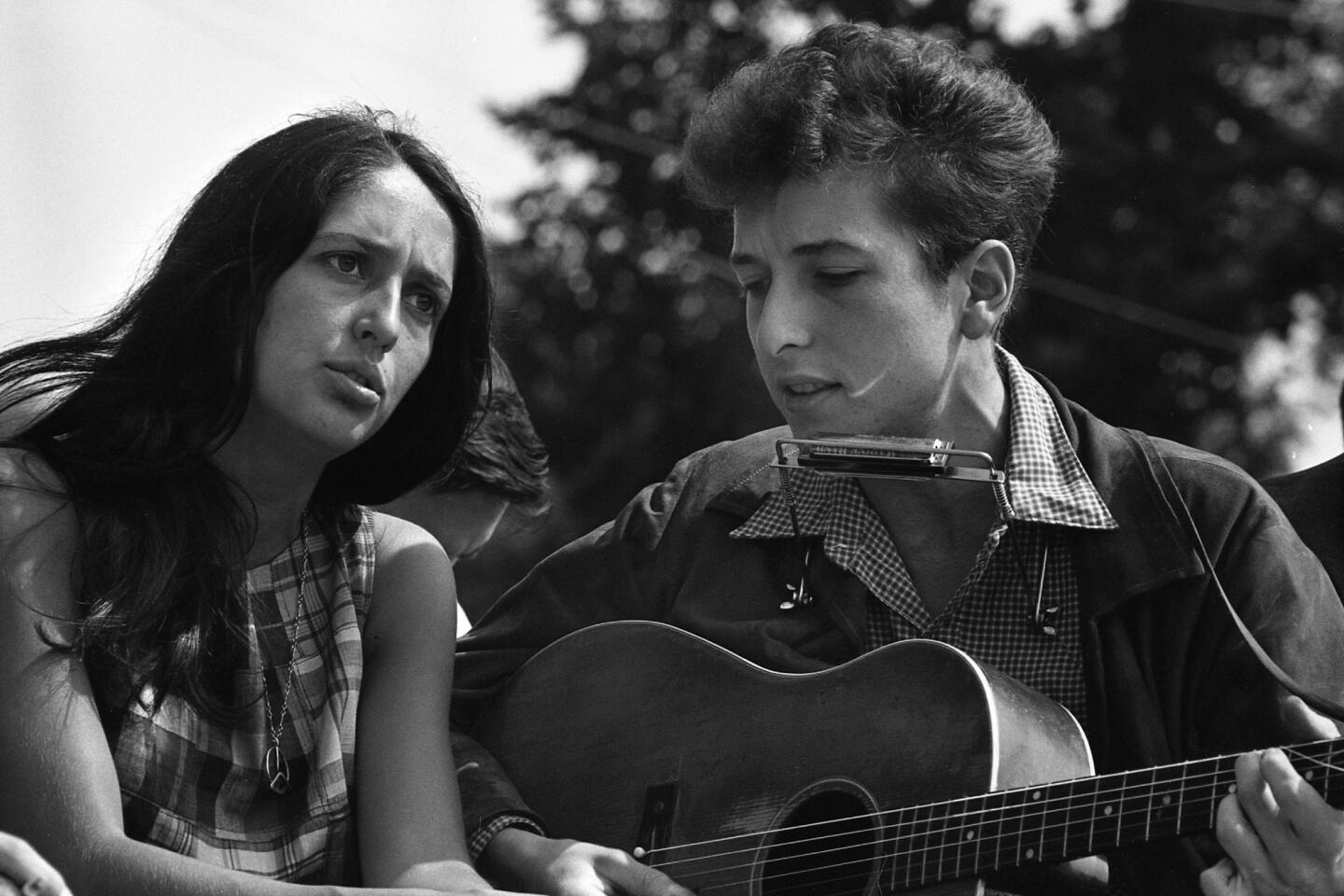

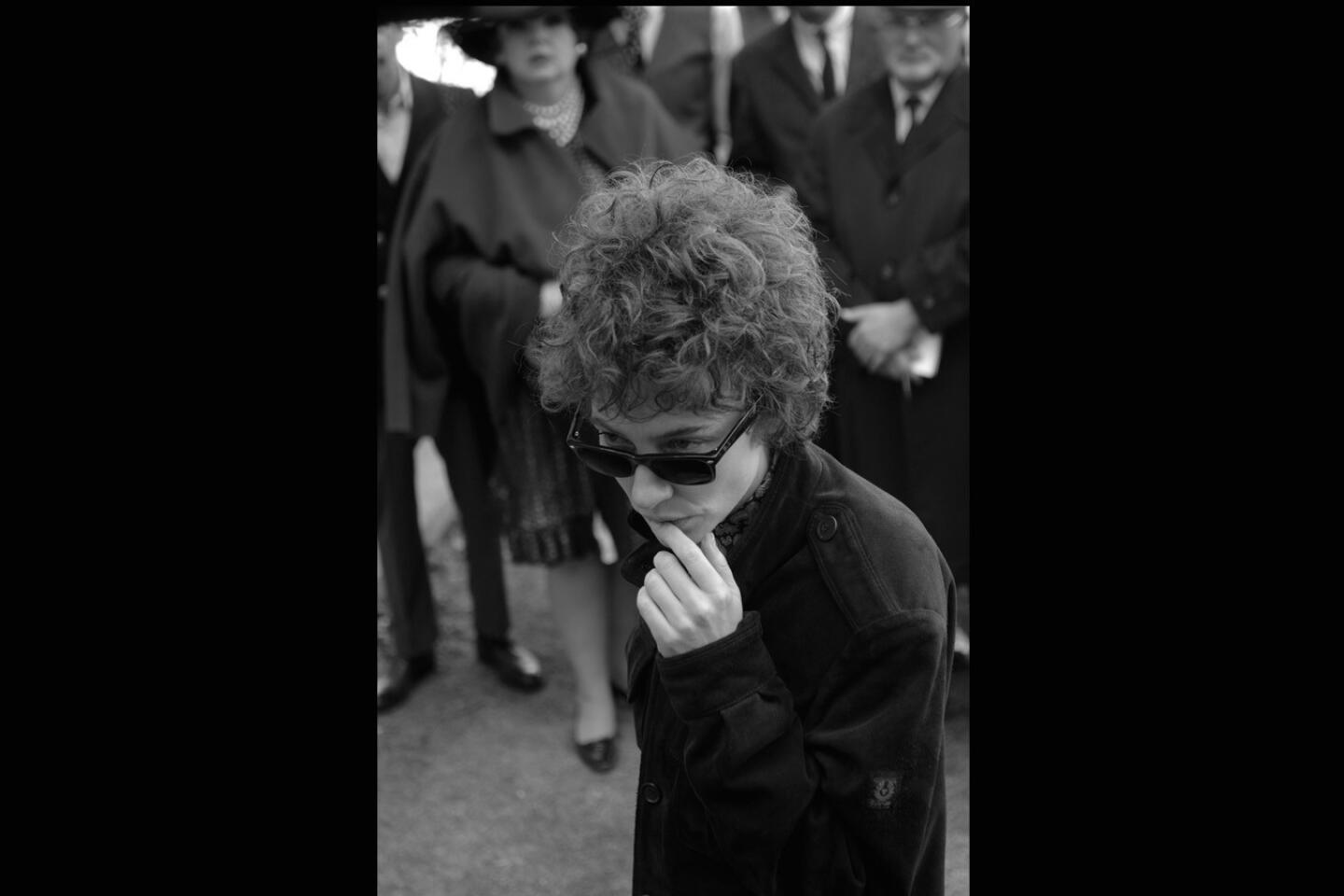

When Dylan made the pilgrimage from his home in Hibbing, Minn., to the vibrant folk music revival scene anchored in New York City’s Greenwich Village in the late 1950s, he came armed with a trove of songs by Woody Guthrie, Lead Belly, Robert Johnson and other folk and blues musicians.

Initially, he was but one of hundreds of aspiring folkies performing songs written by others. Quickly discovering that folk music kingpin Ramblin’ Jack Elliott also was touting Guthrie’s music to younger audiences in New York, Dylan began to put more effort into writing his own songs.

His 1962 debut, “Bob Dylan,” showed a young artist strongly out of the traditional folk realm, singing versions of folk, country and blues standards such as “House of the Risin’ Sun,” “Man of Constant Sorrow,” “Pretty Peggy-O” and “Baby, Let Me Follow You Down.”

He quickly shot to the top of the folk music heap with his next album, “The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan,” which contained several soon-to-be classic songs — “Blowin’ in the Wind,” “A Hard Rain’s a-Gonna Fall,” “Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right” and “Masters of War.”

Other musicians quickly took notice of the budding musical poet. Folk trio Peter, Paul & Mary latched onto “Blowin’ in the Wind,” L.A. rock group the Turtles turned “It Ain’t Me, Babe” into a pop hit, Cher did the same for “All I Really Want to Do,” and the Byrds helped forge a new hybrid of folk and rock with electrified versions of Dylan songs such as “Mr. Tambourine Man” and “My Back Pages.”

A brief look at the catalog of Bob Dylan.

His impact wasn’t limited to a single continent. Emerging at roughly the same time as Beatlemania was igniting in the U.K., Dylan’s music inspired the Fab Four to think beyond the theme of love that dominated their early pop songs.

Where the Beatles’ earliest hits were built around simply stated sentiments such as “I want to hold your hand,” Dylan was writing about love with richly observed sophistication: “I’m a-thinkin’ and a-wonderin’ all the way down the road/I once loved a woman, a child I’m told/I give her my heart but she wanted my soul,” he sang in “Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right.”

In particular, Beatle John Lennon, who had grown up reading the great poets and often entertained himself scribbling fanciful wordplay in the vein of Lewis Carroll, took notes of Dylan’s songwriting and soon moved it into more self-reflective material such as “Help!” and “Girl.”

Dylan’s songs were so plentiful and consistently original that they seemed to pour down through him from the heavens.

Of “Like a Rolling Stone,” Dylan told The Times’ then-pop music critic Robert Hilburn in 2004 that songwriting was often a mysterious process. “It’s like a ghost is writing a song like that,” Dylan said. “It gives you the song and it goes away, it goes away. You don’t know what it means. Except the ghost picked me to write the song….

“I wrote ‘Blowin’ in the Wind’ in 10 minutes, just put words to an old spiritual, probably something I learned from Carter Family records. That’s the folk music tradition. You use what’s been handed down. ‘The Times They Are a-Changin’ is probably from an old Scottish folk song.”

He is the Homer of our time. The next Bob Dylan will not come around for another millennium or two, making it highly unlikely that it will happen at all.

— T Bone Burnett

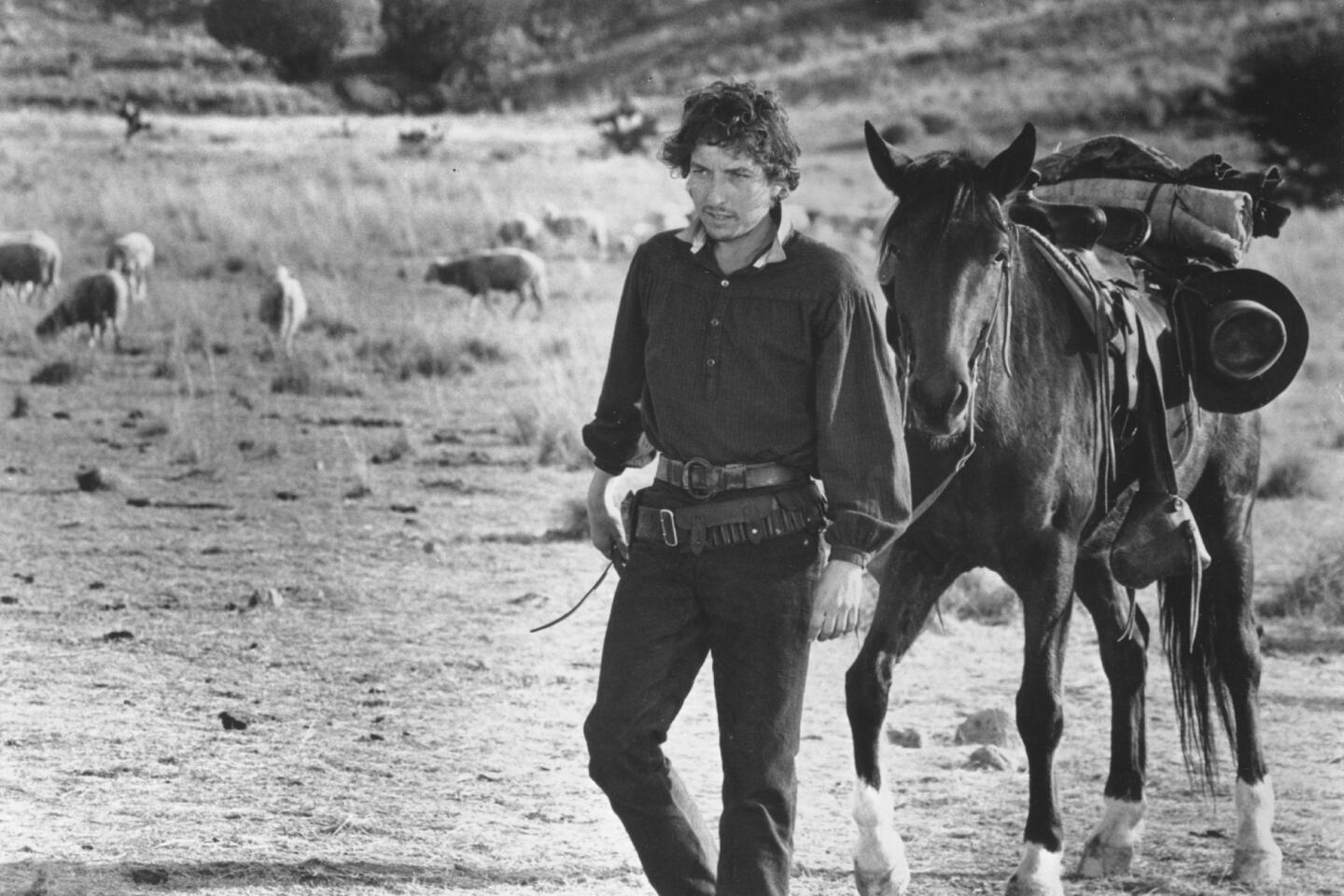

For all the profound influence his 1960s songs exerted, that impact continued in the next decade, when he returned to touring in 1974 after a long hiatus with the album “Planet Waves,” which included another of dozens of his songs recorded multiple times by other artists, “Forever Young.”

He offered up what sounded like a blessing to a generation that had gone to hell and back during the turbulent 1960s with all the turmoil created by the Vietnam War, the civil rights movement, the emergence of women’s liberation and other social and political concerns: “May you grow up to be righteous/May you grow up to be true/May you always know the truth/And see the lights surrounding you.”

His next album, “Blood on the Tracks” in 1975, was considered a full-blown return to form and triggered Rolling Stone magazine to devote thousands of words of commentary from multiple writers exploring the meaning of songs such as “Tangled Up in Blue,” “Idiot Wind,” “Simple Twist of Fate” and “Lily, Rosemary and the Jack of Hearts.”

“Tangled Up in Blue” opened the album with another expansive tale, a careening literal and metaphorical road trip. And again, Dylan offered a nod to the power of poetry in one verse: “Then she opened up a book of poems/And handed it to me/Written by an Italian poet/From the thirteenth century/And every one of them words rang true/And glowed like burnin’ coal.”

Dylan’s foundational place in pop music also gave rise to a music industry phrase that has functioned over time either as a badge of honor or a kiss of death to those tagged as “the new Dylan,” a club that’s included Springsteen, John Prine, Loudon Wainwright III and Steve Forbert.

“There is no way to accurately or adequately laud Bob Dylan,” producer, songwriter and musician T Bone Burnett once said. “He is the Homer of our time. The next Bob Dylan will not come around for another millennium or two, making it highly unlikely that it will happen at all.”

ALSO

In a ‘radical’ choice, Bob Dylan wins the Nobel Prize in literature

Critics wonder if Bob Dylan really needs a Nobel Prize

Bob Dylan, interpreter: Seven of the artist’s greatest covers

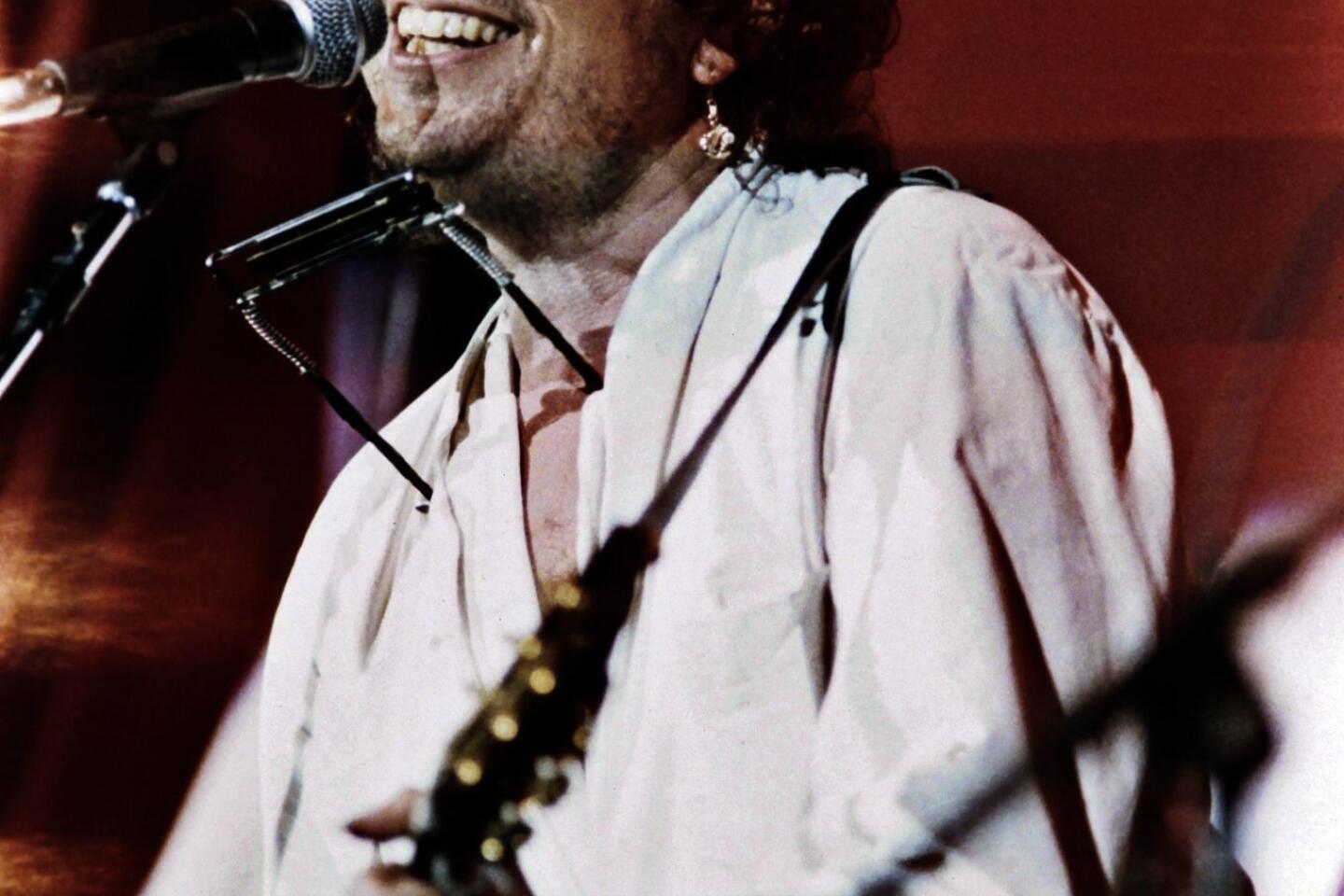

Celebrating Dylan’s late career work, when he started getting obsessed with death

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.