WikiLeaks film shifts focus after Julian Assange won’t share info

When director Alex Gibney began work on his documentary “We Steal Secrets: The Story of WikiLeaks,” he thought he would be telling the story of a charismatic, silver-haired free speech advocate named Julian Assange, who had exposed dark corners of powerful governments and corporations using little more than his laptop.

Instead, as he began to investigate, Gibney found himself crafting a digital age Icarus tale, in which the WikiLeaks founder’s idealism and ambition were metastasizing into hubris, and his organization’s greatest achievements rested on the shoulders of a lonely young Army private named Bradley Manning.

FOR THE RECORD:

“Wiki-Leaks”: A May 19 article about the documentary “We Steal Secrets: The Story of WikiLeaks” identified producer Marc Shmuger as a former Universal Pictures co-chairman. He was chairman. —

In portraying the battle between WikiLeaks — Assange’s group, which publishes classified information supplied by anonymous sources — and its chief adversary, the U.S. government, Gibney delivers a movie about government transparency in the Internet era, an especially resonant topic in a month when it was revealed that the Justice Department secretly gathered the phone records of Associated Press journalists and the IRS targeted tea party groups.

The movie, which opens May 24 in Los Angeles and New York, is also timely for another reason — it provides the most intimate portrait yet of Manning, whose court-martial for allegedly providing WikiLeaks with hundreds of thousands of classified documents is set to begin June 3 at Maryland’s Fort Meade.

“I thought this film was about a leaking machine, this new technology, and I thought it was about this silver surfer character Julian Assange, who had this great David and Goliath story,” Gibney said over coffee last month. “But in some ways it’s a reflection of how important it is to constantly be examining what is true and what is not.”

Producer Marc Shmuger, a former Universal Pictures chairman, originally brought the idea of making a WikiLeaks movie to Gibney, who won an Oscar for his 2007 Afghan war documentary “Taxi to the Dark Side,” and has developed a kind of micro-niche of movies about the downfall of arrogant men and institutions — he directed “Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room,” about the bankrupted energy company; “Casino Jack and the United States of Money,” about corrupt Washington lobbyist Jack Abramoff; “Client 9: The Rise and Fall of Eliot Spitzer,” about the prostitution scandal that felled the New York governor; and “Mea Maxima Culpa: Silence in the House of God,” about the sex abuse crisis in the Catholic Church. This fall, his documentary about Lance Armstrong is due.

“Assange, from the first time I was exposed to him, just seemed like the most fascinating subject and the kind Alex does a tremendous job in his films exploring — subjects that are textured and morally complex and compelling,” Shmuger said. “You’re both drawn to him and repulsed by him simultaneously.”

Gibney and Shmuger weren’t the only filmmakers drawn to Assange; when they started on the documentary, three narrative movies about the Australian computer hacker were in various stages of development. Since then, only one has gone forward, director Bill Condon’s “The Fifth Estate,” which stars Benedict Cumberbatch as Assange and arrives in theaters in November.

Gibney penetrated the dense circle of agents, lawyers and journalists who surrounded Assange with the help of one of his film’s executive producers, activist Jemima Khan, who had posted some of Assange’s bail in a case involving allegations of sexual abuse by two Swedish women.

After months of discussions about Assange’s possible participation in his film, Gibney flew to England, where his subject was living under house arrest in a country estate, for a six-hour meeting. According to Gibney, at that meeting Assange told him the going rate for an interview was $1 million. When Gibney said he didn’t pay for interviews, Assange asked if instead the director would tell him what others interviewed in the documentary were saying.

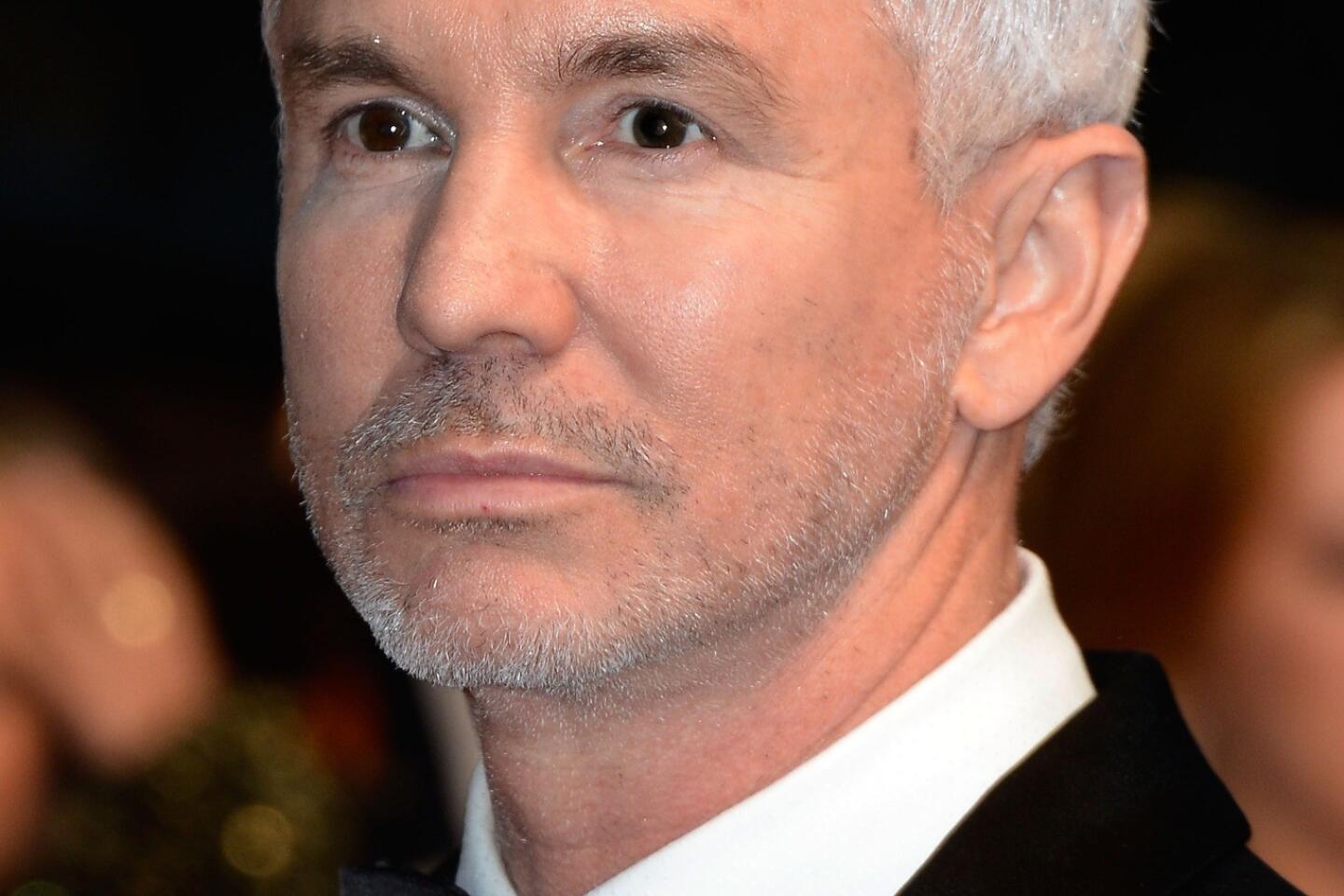

“He didn’t see the irony at all,” said Gibney, 59, an unusually prolific filmmaker who often has multiple projects proceeding at the same time. “To him, he was ... being attacked by big and powerful forces and he should have the right to do whatever is necessary to protect himself. The idea that spying on other interview subjects would be ironic for a transparency organization didn’t occur to him at all.”

Assange declined to cooperate with Gibney, which led the director to mine other sources, including footage an Australian journalist shot of Assange before he was famous, and to find another story — Manning’s.

Manning, a former intelligence analyst, faces charges of violating the Espionage Act and aiding the enemy in the most voluminous leak of state secrets in U.S. history, including video of a 2007 Baghdad airstrike and hundreds of thousands of diplomatic cables and Army reports.

Physically small and emotionally vulnerable, Manning emerges as a character in the film through a series of painfully intimate online chats he conducted using the handle Bradass87 with the hacker Adrian Lamo, who served as a confessor and friend before ultimately turning Manning in to authorities.

“The chats presented a technical problem in terms of what you’re supposed to do in film,” Gibney said. “You’re not supposed to put a lot of print up on screen.”

But with the help of the London-based visual effects company Framestore, Gibney began to experiment with telling that story that way — and some of the movie’s most dramatic moments come in the form of white text on a black screen, over the sound of a tapping keyboard.

At one point, Manning, explaining to Lamo why he was leaking information that called into question the morality of the Afghan and Iraq wars, types the phrase, “I... care?”

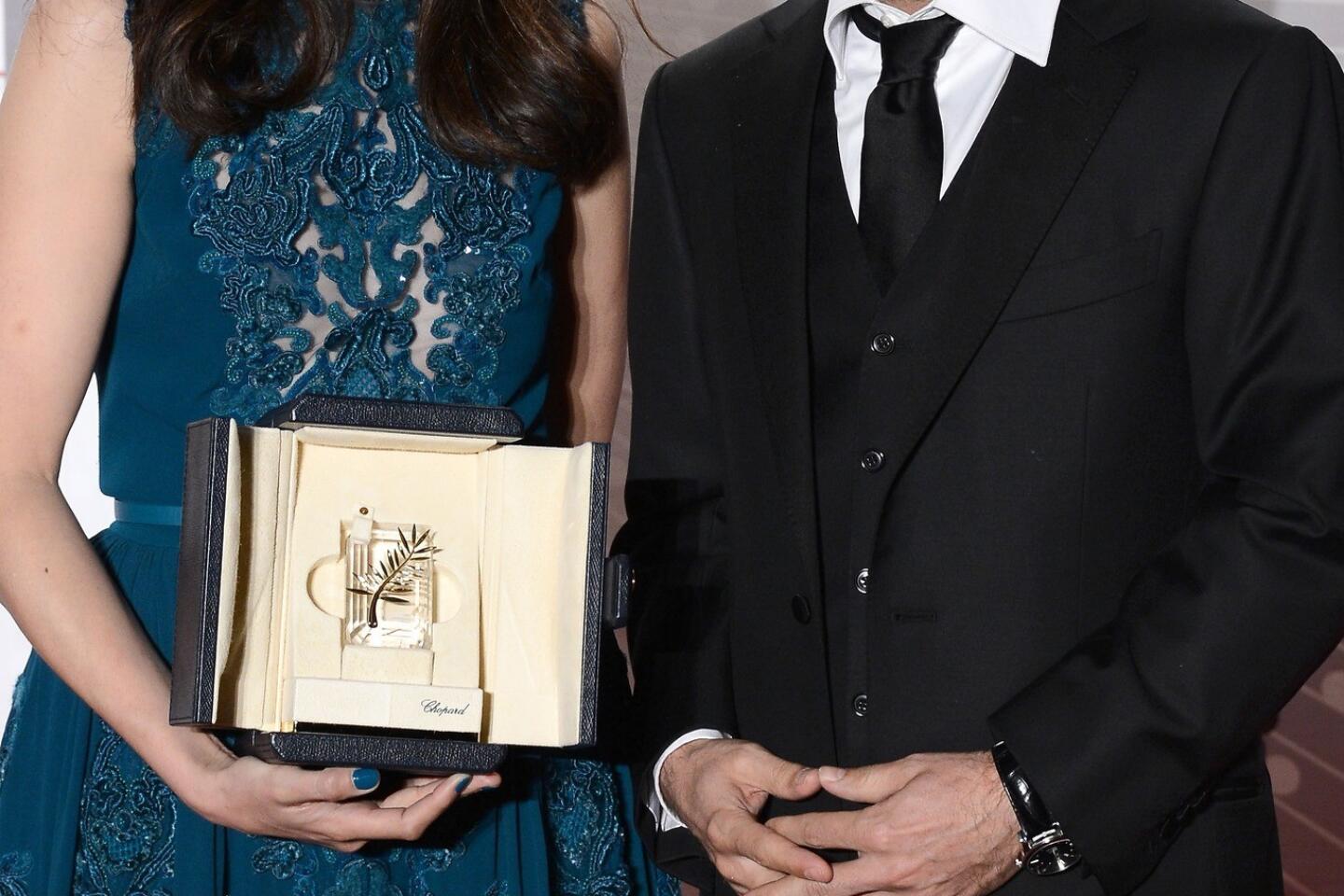

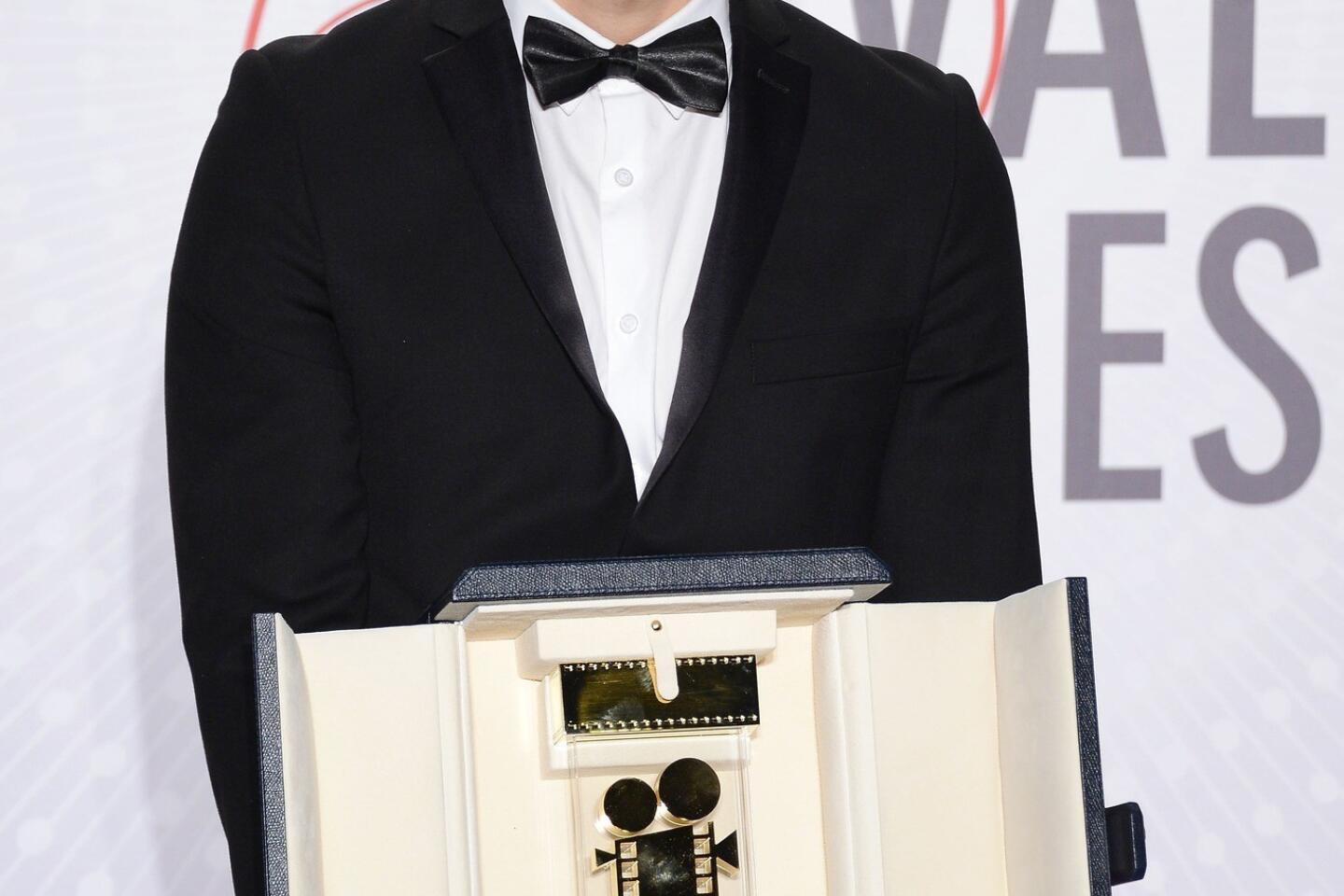

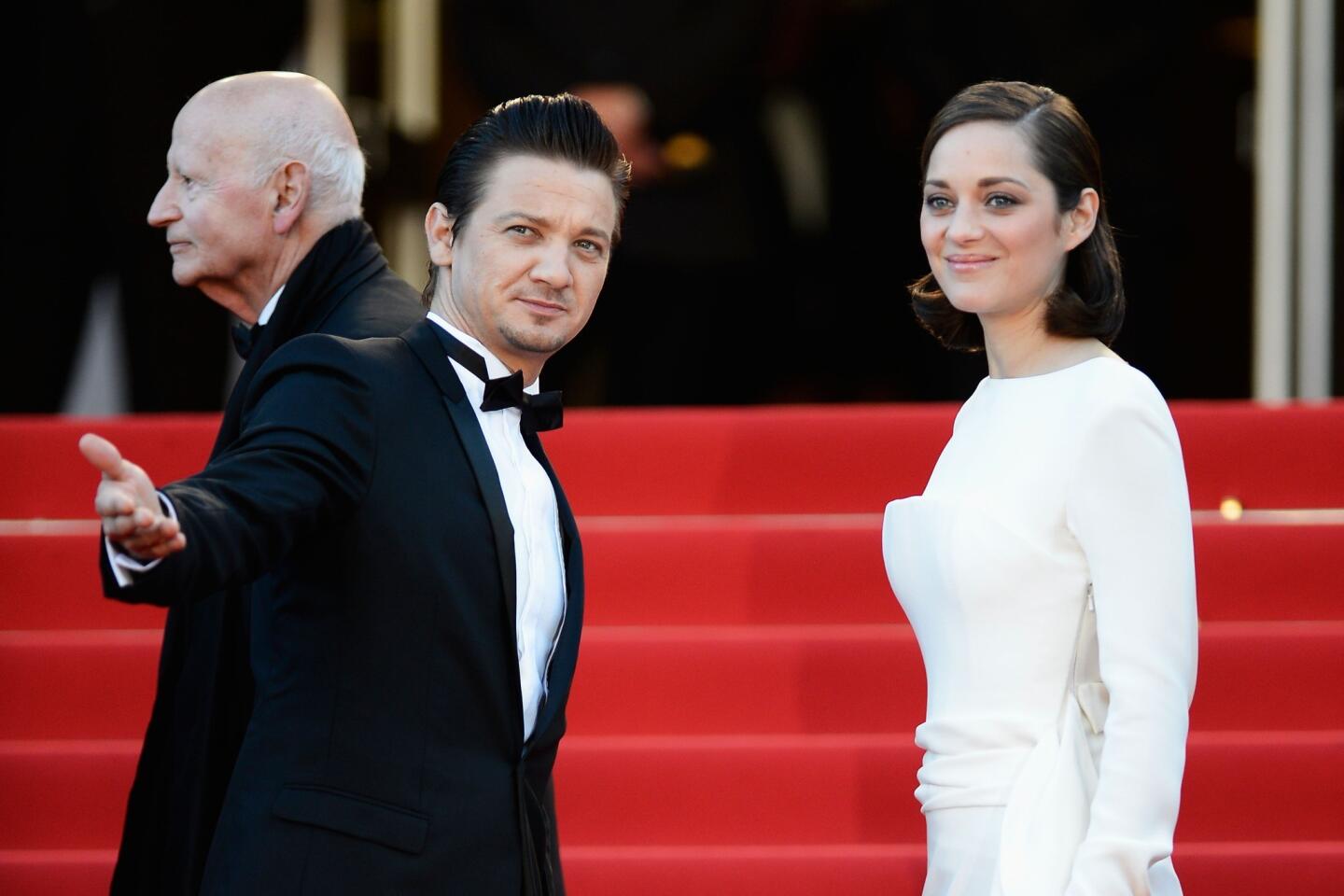

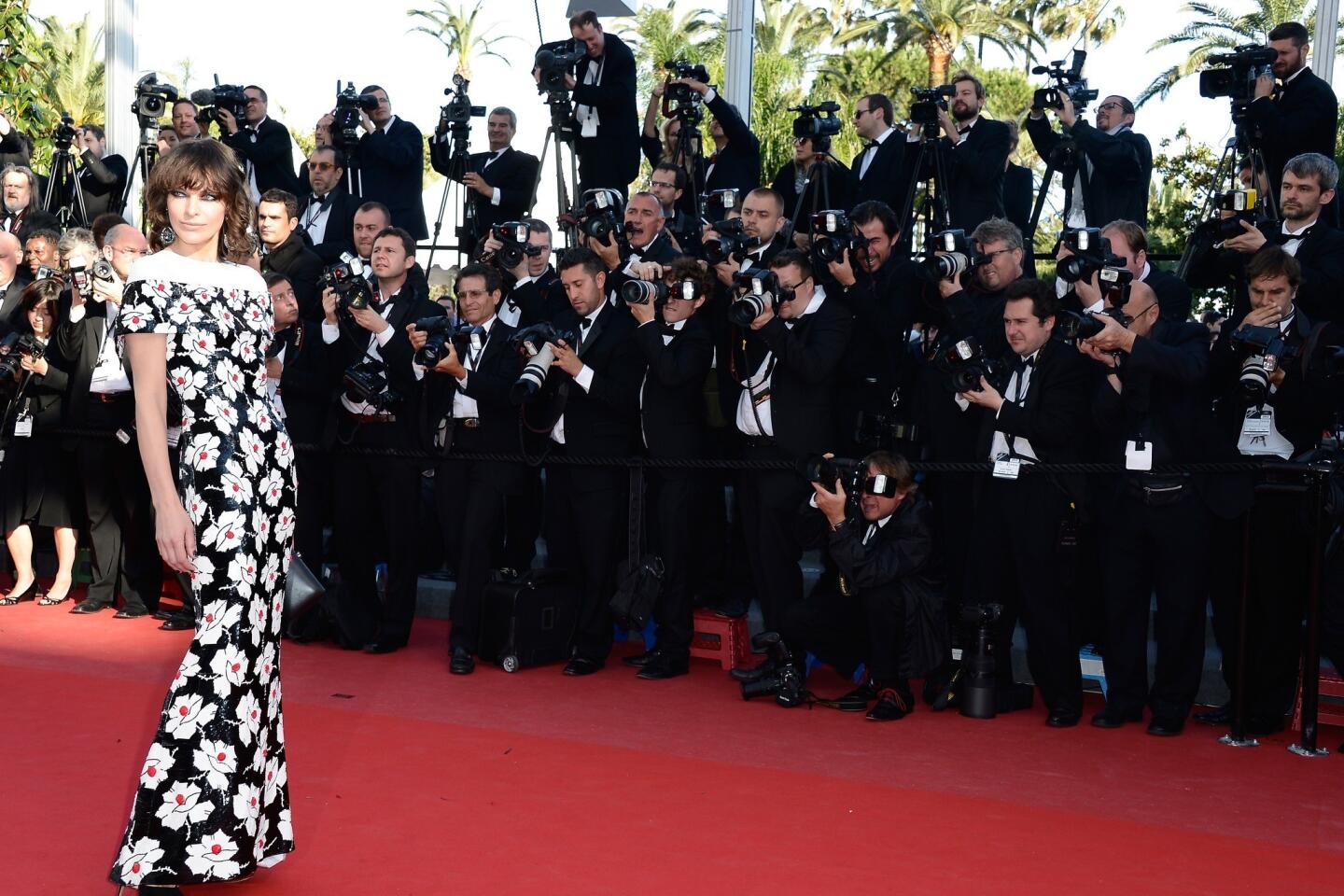

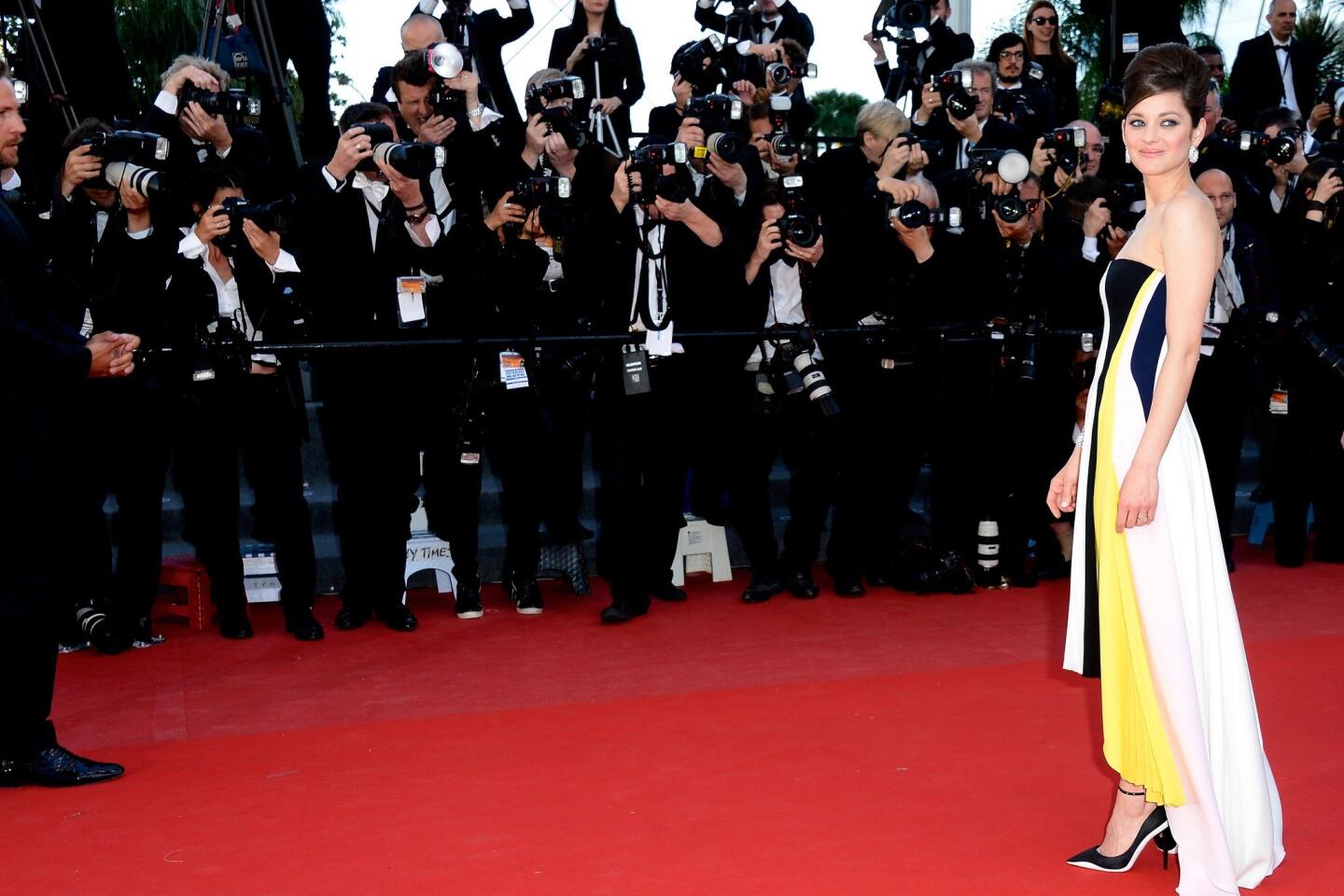

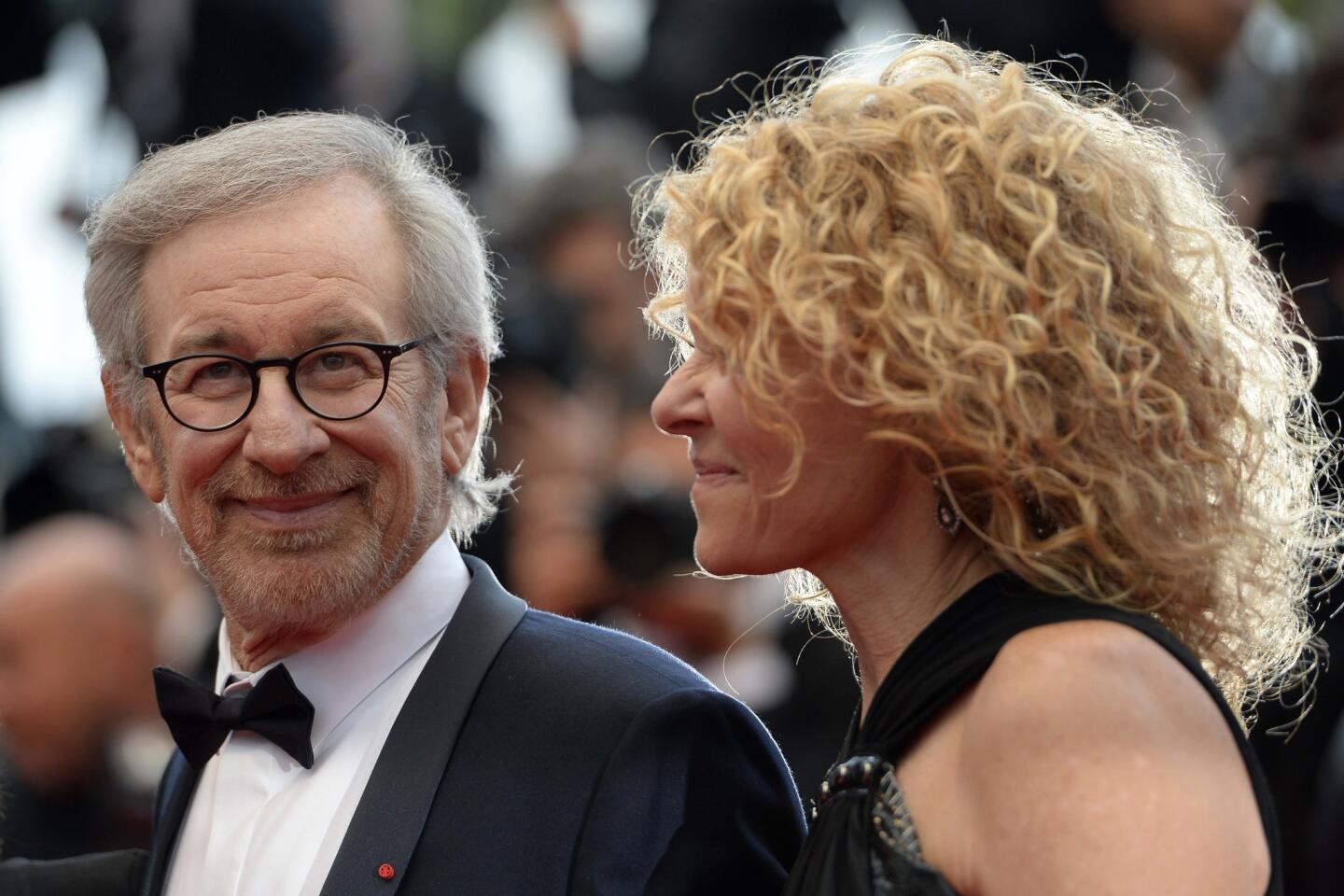

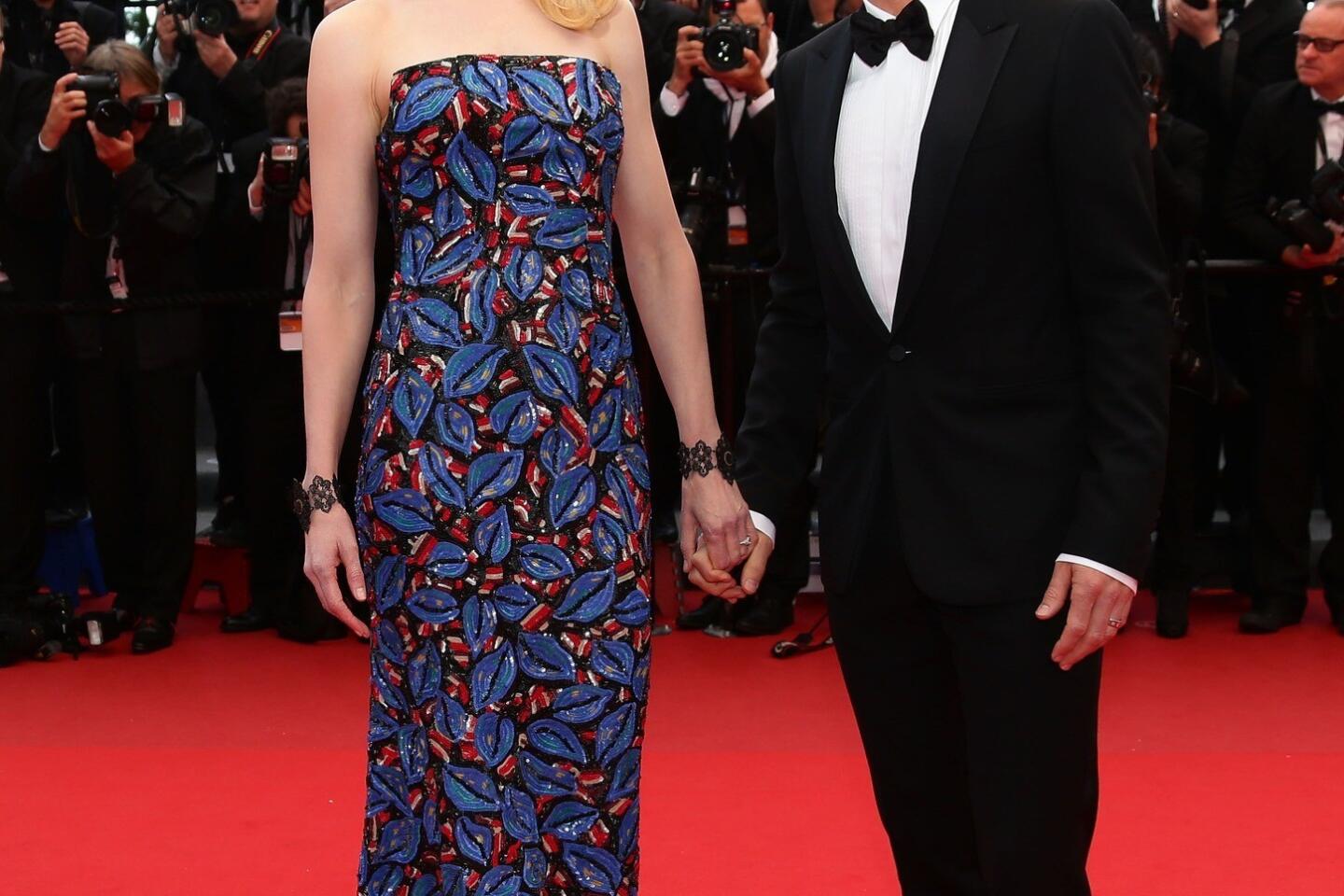

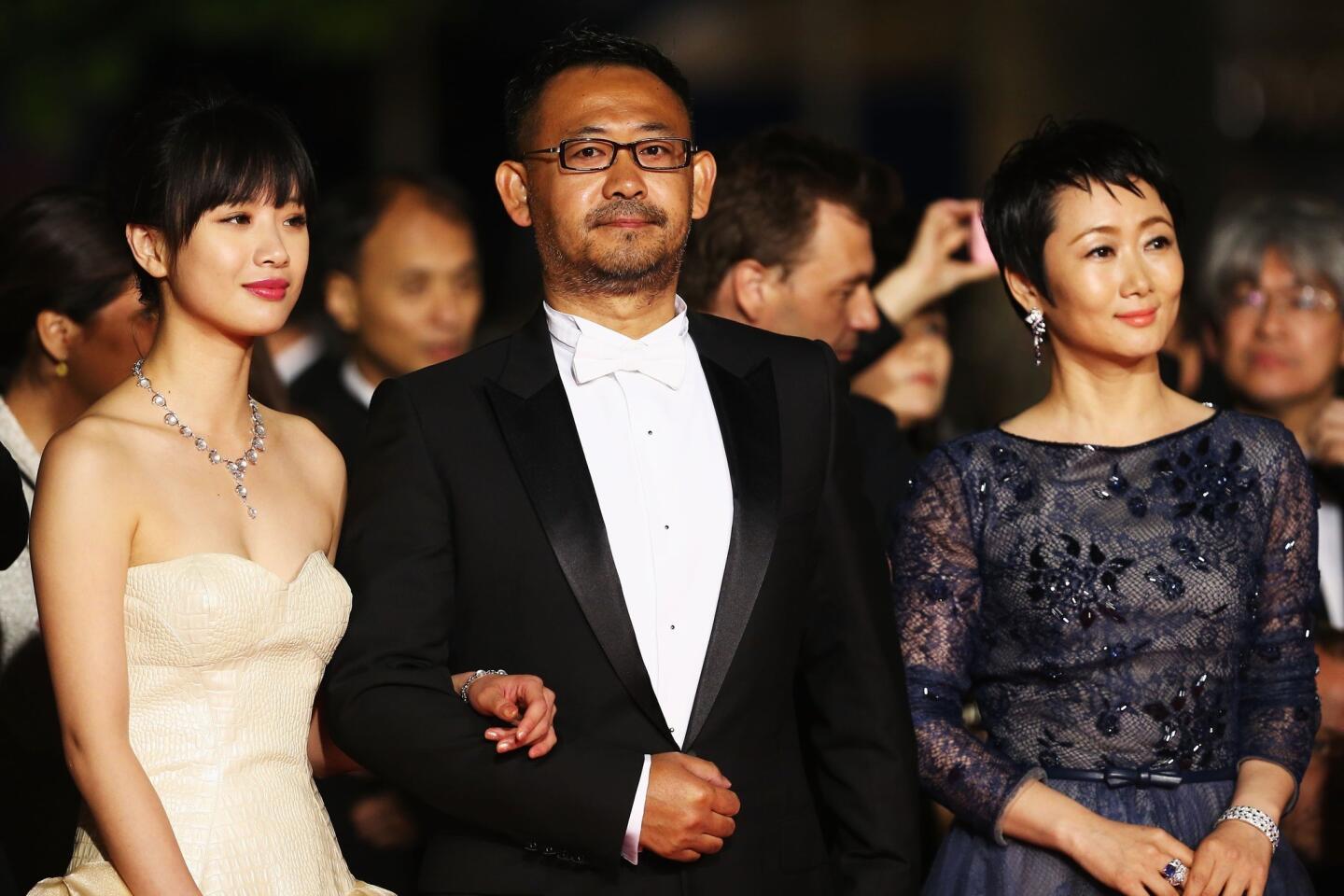

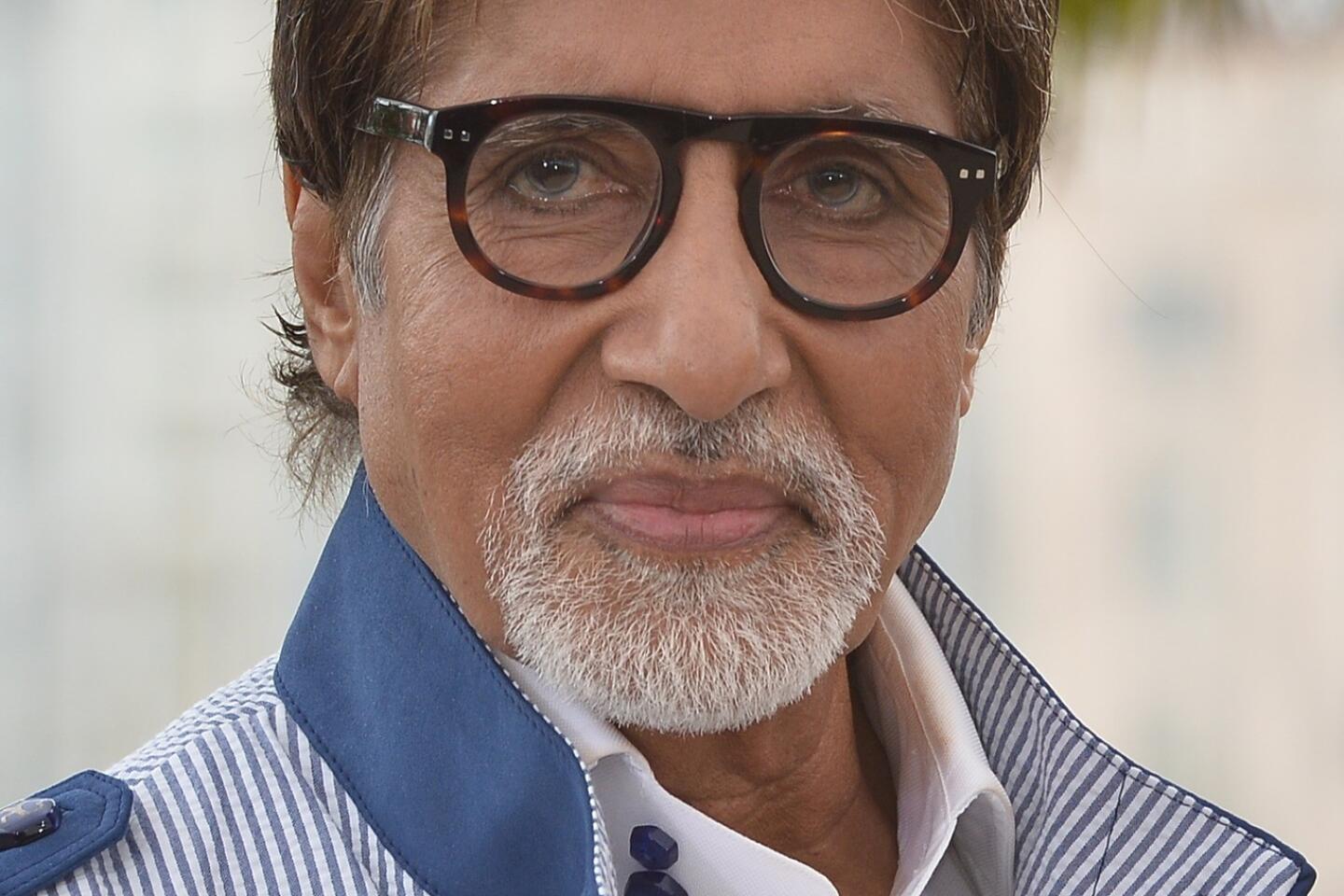

PHOTOS: Cannes Film Festival 2013

“It seems to me both so enigmatic but so important,” Gibney said. “He uses a question mark, not an exclamation point, so it’s shy.... It testifies fundamentally to his commitment.”

After the movie, being released by Focus World, premiered at the Sundance Film Festival in January, Assange supporters denounced it on Twitter using a hashtag with an epithet and Gibney’s name. “For [Assange’s supporters] it’s all about white and black, about propaganda,” Gibney said. “There is only one truth, the truth that Julian tells us. And there can be no dissent. It’s not so dissimilar from Julian’s enemies.”

Today Assange and Manning reside in jails of a type. Assange lives in the Ecuadoran Embassy in London, where he has sought asylum from extradition to Sweden. Manning has spent more than three years in various military prisons awaiting his June trial.

“People say my films are political,” Gibney said. “Maybe they’re political. They’re about moral quandaries. I’m interested in human psychology ... how people handle power, what motivates people to do what they do.”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.