Review: ‘The Wind Rises’ a soaring swan song for Hayao Miyazaki

To see “The Wind Rises” is to simultaneously marvel at the work of a master and regret that this film is likely his last.

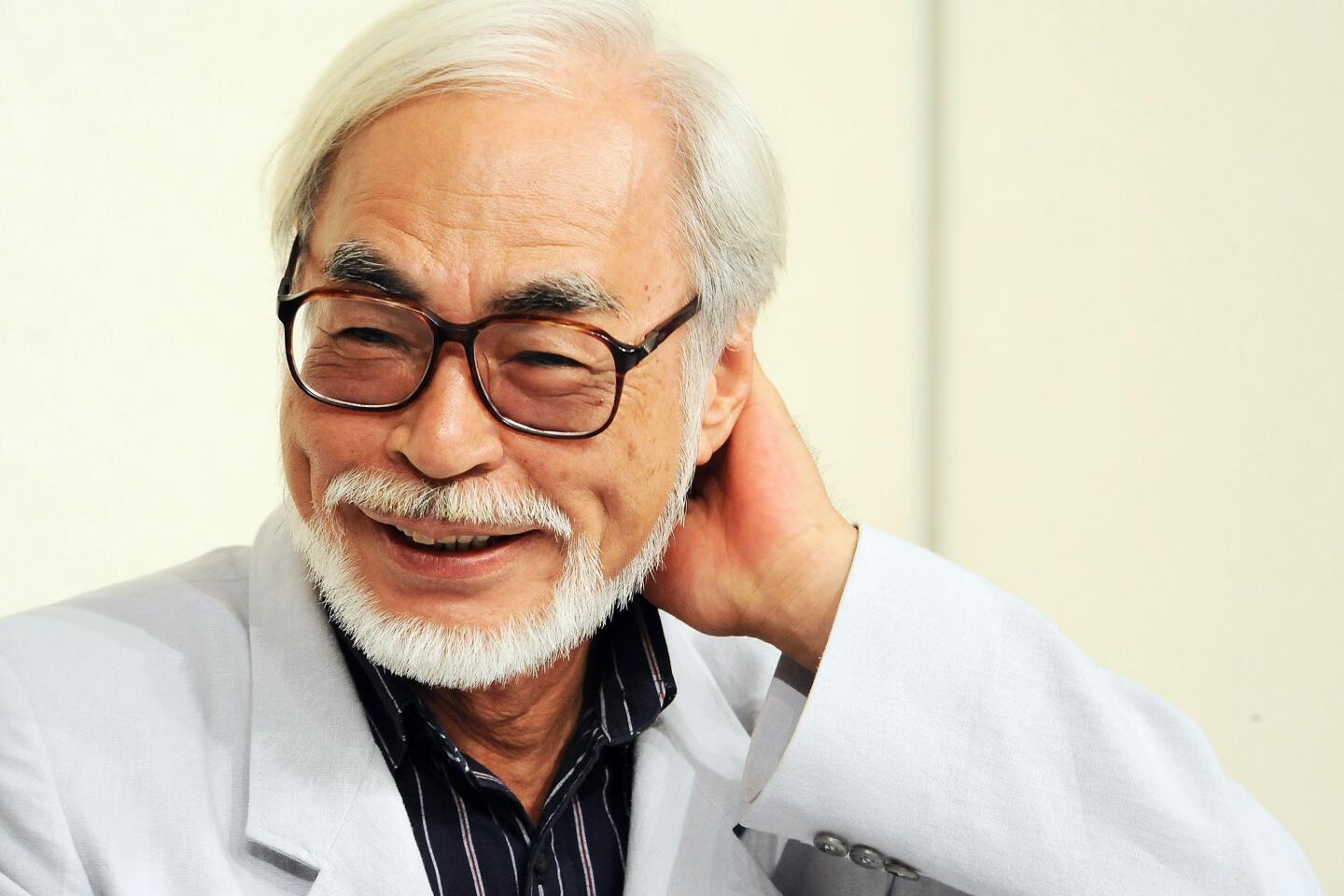

Japan’s Hayao Miyazaki, perhaps the world’s preeminent animator, beloved for “My Neighbor Totoro” and an Oscar winner for “Spirited Away,” has announced his retirement. If he holds to that, it’s fitting that this final film, inspired by but not limited to the life of brilliant aircraft designer Jiro Horikoshi, is quintessentially his: stunningly beautiful and completely idiosyncratic.

Always determined to tell his kind of stories his way, Miyazaki has returned to subject matter close to his heart — the joy and romance of airplanes and flight, most fully explored in 1992’s “Porco Rosso” — but he’s elected to tell it in a manner new to him.

PHOTOS: Hayao Miyazaki, an animated icon

The great fantasist of contemporary animation celebrated for subject matter that has great appeal to children, Miyazaki has chosen to end his career with an inspired-by-history story that has adult relationships at its core.

Yet because this is Miyazaki, even the most realistic sequences, such as those dealing with the Great Kanto Earthquake and fire of 1923, are jaw-dropping visual knockouts. You can feel the care that goes into every hand-drawn frame here, and the emotion that conveys the director’s sense of wonder at the pleasures of the physical world.

One of the world’s great aeronautical engineers, Horikoshi is an unusual choice for a fervent pacifist like Miyazaki to make a film about because his most celebrated aircraft was the feared Zero fighter plane that attacked Pearl Harbor.

Though it is possible, as some writers in Japan have speculated, that Miyazaki intended his film to be part of the country’s current debate about increased militarization, the director insists he was inspired by something completely apolitical, a quote he read of Horikoshi’s: “All I wanted to do was make something beautiful.”

“I wanted to portray a devoted individual who pursed his dream head on,” Miyazaki wrote in his initial proposal for the film. “Dreams possess an element of madness, and such poison must not be concealed. Yearning for something too beautiful can ruin you. Swaying toward beauty may come at a price.” Anyone who considers animation good for only Hollywood piffle will certainly have their heads turned watching this.

“The Wind Rises” begins, not surprisingly, with Horikoshi’s childhood in the World War I era. If the chef in the documentary “Jiro Dreams of Sushi” dreamed of slicing fish, this Jiro literally dreams of soaring through the air, of having an actual airplane parked on his roof that he can use to fly over the stunning, delicately beautiful countryside Miyazaki creates.

Making a cameo in Jiro’s dreams is a personal hero of Miyazaki’s, the visionary Italian aircraft designer Gianni Caproni (whose company manufactured the plane the director’s Studio Ghibli production company is named after). It is Caproni who expresses to Jiro a philosophy akin to Miyazaki’s own: “Airplanes are not for war or making money. Airplanes are beautiful dreams.”

Too near-sighted to fly himself, Jiro is met again as a young adult, a double for Harold Lloyd in straw boater and dark-rimmed glasses, as he takes a train to Tokyo to begin his airplane engineering studies.

On that journey, Jiro not only has to deal with that great Kanto earthquake and fire but he also meets a fellow passenger, a bright young girl named Nahoko who admires the same poems he does. Though the aftermath of the chaos caused by the earthquake separates them for years, Jiro never stops searching for Nahoko.

The central section of “The Wind Rises” deals with Jiro working for aircraft manufacturing giant Mitsubishi and his steady rise through the designing ranks, a visionary pure and simple who just wants to build the best possible aircraft and finds his passion subverted by those in power almost without his realizing it is happening.

PHOTOS: Billion-dollar movie club

We don’t see much of everyday Japan during wartime, but Miyazaki does spend considerable time on prewar situations that possibly influenced the course of history. The cityscapes he depicts may be exquisite, but the poverty of the nation and its feeling of inferiority to the West are disturbing. Horikoshi is portrayed as enough of a free thinker to get into political trouble, but his passion for his ideal plane never falters.

Though Horikoshi is the film’s nominal subject, his personal life has been completely fictionalized by Miyazaki. The film’s melancholy elements, including a charming romantic reconnection with Nahoko, come from the work of Tatsuo Hori, a writer of the pre-World War II era who wrote a novel called “The Wind Rises” that was inspired by the same line from French poet Paul Valery that opens the film: “The wind rises, we must try to live.”

Despite the obstacles and difficulties life and society throw at them, that’s what these characters attempt to do. “The Wind Rises” is a kind of summing up film for Miyazaki, a complex story that resists easy summation, but it is his genius to pull us into this world and make us so not want to leave it. This is a filmmaker who will be missed, and not in a small way.

(“The Wind Rises” is scheduled for a one-week academy consideration run in its subtitled version and will return to theaters in February in a dubbed edition.)

-----------------------------------

‘The Wind Rises’

MPAA rating: PG-13 for some disturbing images and smoking

Running time: 2 hours, 6 minutes

Playing: At Landmark, West Los Angeles

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.