Shane Salerno’s decade-long obsession with J.D. Salinger

When Shane Salerno turned 40 last year, he decided it was finally time to let his obsession go.

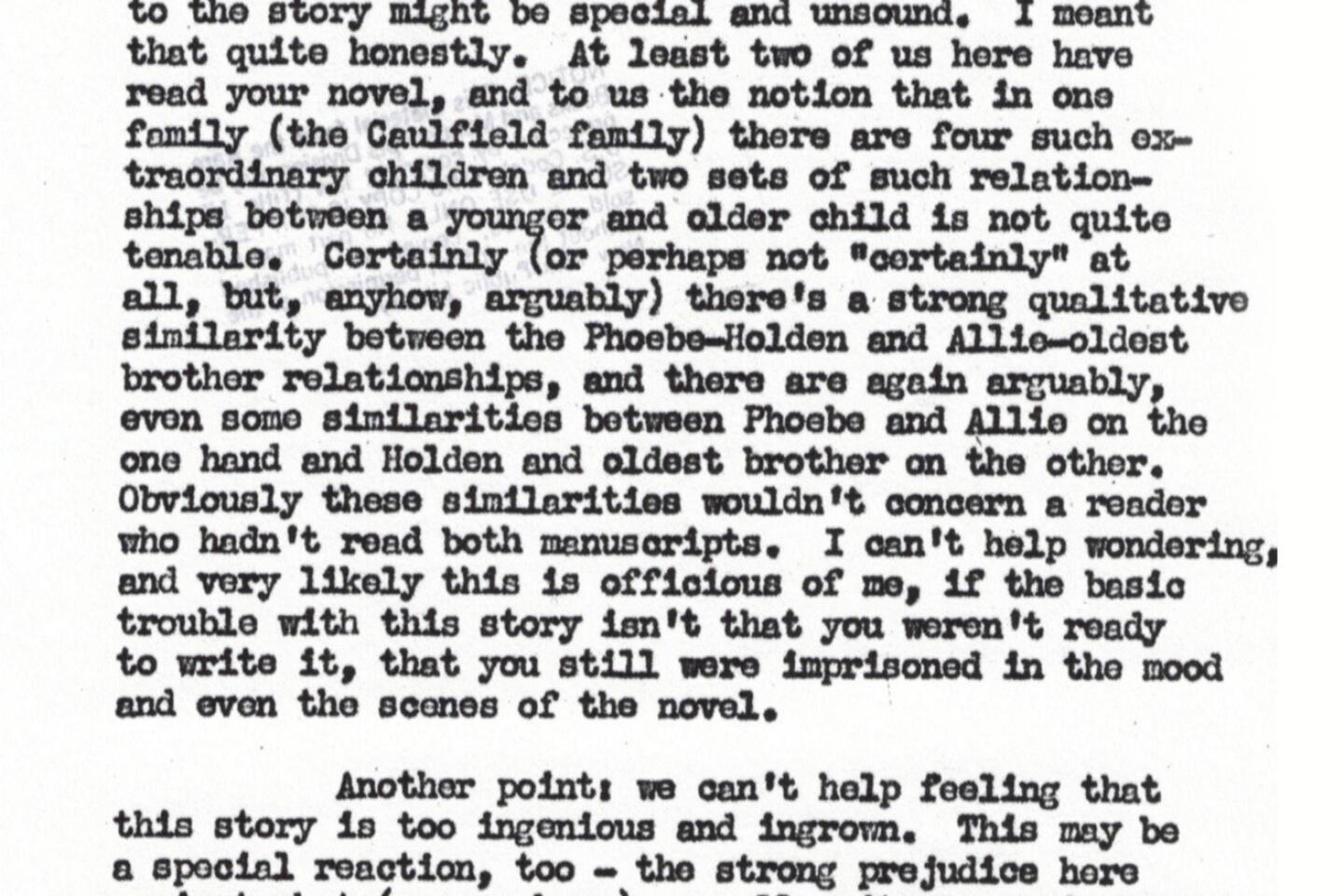

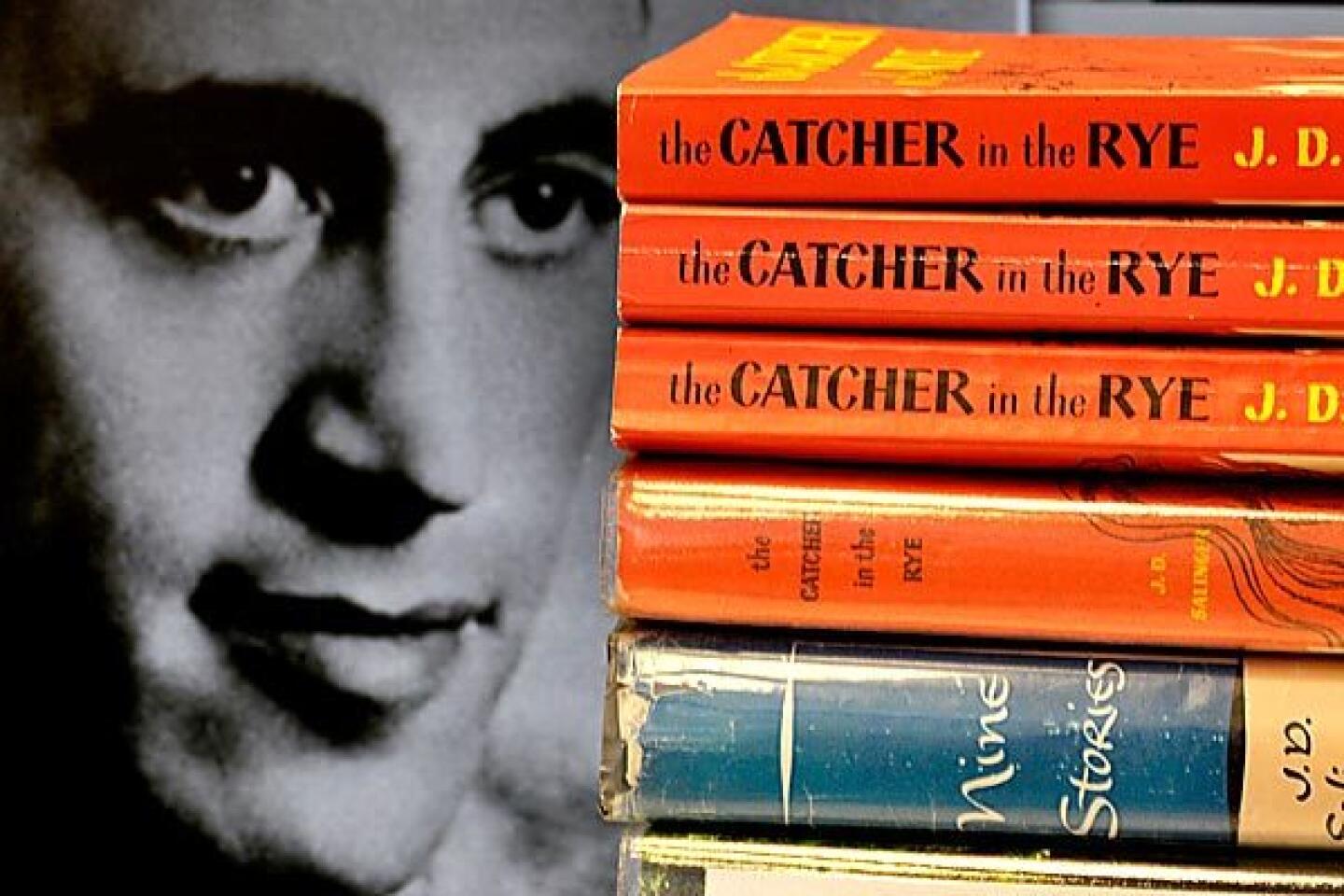

The screenwriter, best known for his collaborations with Michael Bay (“Armageddon”) and Oliver Stone (“Savages”), had toiled for close to a decade trying to document the mysterious life of J.D. Salinger. The author of the bestselling “The Catcher in the Rye” had stopped publishing in 1965 and retreated from the public spotlight, leaving fans to wonder why — and to guess about what he had been doing in the 45 years until his death in 2010.

Over the years, Salerno had discovered juicy details about the enigmatic author — a short-lived marriage to a Gestapo informant at the end of World War II; a long-term relationship with a teenage girl that became the inspiration for the short story “For Esmé — With Love and Squalor”; a previously unknown best friend with whom he had corresponded over five decades. But the biggest revelation of all? Two sources saying that Salinger had left behind five unpublished manuscripts to be released between 2015 and 2020.

PHOTOS: J.D. Salinger | 1919-2010

The plan was to pour all the research into an exhaustive biography co-written with David Shields and simultaneously release a two-hour film. But every time Salerno thought he had uncovered it all, new information would trickle in.

At last, he had reached his limit. “I turned 40 and I was done,” recalled Salerno, sitting in his Brentwood office last week among the letters, photographs and documents that have consumed his life. “The film was sitting in my house as a finished master and I thought: ‘This is ridiculous, enough.’ On Dec. 3, I called my lawyer and I said, ‘I want to do this now.’”

Nine months later, the result is a 698-page oral biography, “Salinger,” published Tuesday, and a documentary of the same name that’s arriving in theaters Friday after premiering last weekend at the Telluride Film Festival. Early reviews have described both works as engrossing as well as exasperating, and time will tell how deeply Salerno’s passion project resonates with a wider audience.

“I always trusted that he had what he said he had,” said Salerno’s attorney, Robert Offer. “What I didn’t trust was that anyone would care as much as they did.”

Project’s birth

The Salinger project began as a lark. Although the author’s work and mystique loomed large in Salerno’s household as a child (Salerno’s mother loved “Franny & Zooey” while her son was partial to “A Perfect Day for Banana-Fish” and “Esme”), his quest started in 2003, when he was in a bookstore and found the cover of Paul Alexander’s biography of Salinger which featured two incongruous photos of the author superimposed — a youthful cover portrait from “Catcher in the Rye” and a candid shot taken much later at the writer’s home in Cornish, N.H. The images depicted a man young and old, optimistic and deflated.

PHOTOS: Telluride Film Festival 2013

“I was so taken with that image that I spent 91/2 years trying to find out what happened,” said Salerno, who originally thought he would spend $300,000 and six months investigating Salinger. He wound up using $2 million of his own money.

After a privileged New York upbringing, military school as a teen and a brief stint in college, Salinger was struggling as a writer when World War II broke out. He entered the Army and was sent to Europe; Salerno said it was Salinger’s trajectory during and after the war that kept him in the hunt for so long.

“The moment I said, ‘No matter what it takes, I’m going to finish the film,’ was when I learned that he went into a concentration camp [at the end of the war], went to a mental institution as a result and did what no other person on the planet would do: He signed up for more,” Salerno said. “He joined the de-Nazification program and decided to go hunt these guys down. The minute I heard that, I was there.”

Salerno made trips to Germany, Chile and many places on the East Coast, trying to piece together Salinger’s back story. He says that although certain members of the author’s family initially cooperated with his quest, they ultimately didn’t participate in formal interviews. But Salerno, Shields and his crew, which included cinematographer Buddy Squires (“The Central Park Five”), were propelled by gets, such as a photograph of Salinger in his bedroom or a trove of letters that Salinger exchanged with author Joyce Maynard.

At times, Salerno seems to adopt a Salingeresque secrecy about his own work; ask him, for example, whether he’s seen any of the actual manuscripts he says are awaiting publication and he refuses to answer. And he says he never sought to interview the man directly. Yet Salerno is happy to wax on about what he sees as the significance of the book and film.

“This was an extraordinarily difficult project. This wasn’t doing Ted Kennedy or Steve Jobs, where there are 100 or 200 interviews that you can draw on,” he said. “We were having to pull things out of thin air.”

Teen girls

One of the most compelling — and disturbing — segments of the film concerns Salinger’s predilection for teenage girls. The movie touches on Salinger’s early romance love with high-schooler Oona O’Neill (who would later marry Charlie Chaplin), and describes his multiyear courtship of Jean Miller, whom he met at Daytona Beach, Fla., when she was 14 and he was 30. It also delves into his relationship with Claire Douglas, whom he met when she was 16 and who became his second wife and mother to his two children.

In the film, Miller, now 78, describes their correspondence, her trips to his house in Cornish, how they danced to “The Lawrence Welk Show” and watched Frank Capra’s “Lost Horizon.” She says that when she was 19, and he 35, she lost her virginity to him and he ended the relationship immediately.

It was a pattern Salinger would repeat at age 53 with the then-18-year-old Maynard, who came to his attention when she was featured on the cover of the New York Times Magazine for her essay on life as a teenager. Maynard dropped out of Yale University after her freshman year and lived with Salinger for 10 months, writing her first novel at his house before he ended the relationship abruptly. Maynard attended the film’s premiere in Telluride, Colo., and said she was more agitated by the movie than she expected to be.

WATCH: Trailers from Telluride

“Salinger’s interest in seeking out young girls is certainly an element in the film. But the disturbing consequences of this behavior, to the girls, is barely addressed, and the suggestion has been made that there was some kind of privilege or honor involved in having been selected as a muse,” Maynard said in an interview. “It is my view that J.D. Salinger damaged the lives of many young girls, on a far greater scale than is represented in Salerno’s film.”

Salerno said he was bothered by what he learned about Salinger’s interest in teenagers but added that he cut more information about those relationships from the film due to space constraints. (The book includes another story about a 16-year-old, Shirlie Blaney, whom Salinger had a brief relationship with when he was in his early 30s.)

“We felt after Oona, Joyce, Jean and Claire, the point had been made,” said Salerno. “When we showed people early cuts of the film, they were like, ‘We get it.’”

Coming to PBS

Salerno, who recently signed on to write James Cameron’s “Avatar 4,” has sold the TV rights to the Salinger film to PBS, and after its theatrical run, it will air on “American Masters” next year.

Salerno’s only hope now is that people like it.

“I had to make this film, and I’m sure someone could have made it better, made it different, but I know that I gave it everything I had for nine years,” said Salerno. “I really hope people enjoy it and feel that it honors Salinger, but tells the full story of his life. That was a really hard line. Yes, he’s an extraordinary artist and a deeply complicated human being.”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.