An unusual departure for beloved Japanese animator Hayao Miyazaki

The busiest moment in the history of Twitter happened in August when multitudes of Japanese users tweeted the word “balus” while watching a TV broadcast of director Hayao Miyazaki’s 1986 animated movie, “Castle in the Sky.”

In an indicator of Miyazaki’s cultural influence in his high-tech homeland, the made up word, which translates roughly as “destruction,” garnered more tweets per second (143,199) than such buzzed about events as the birth of Prince William’s son.

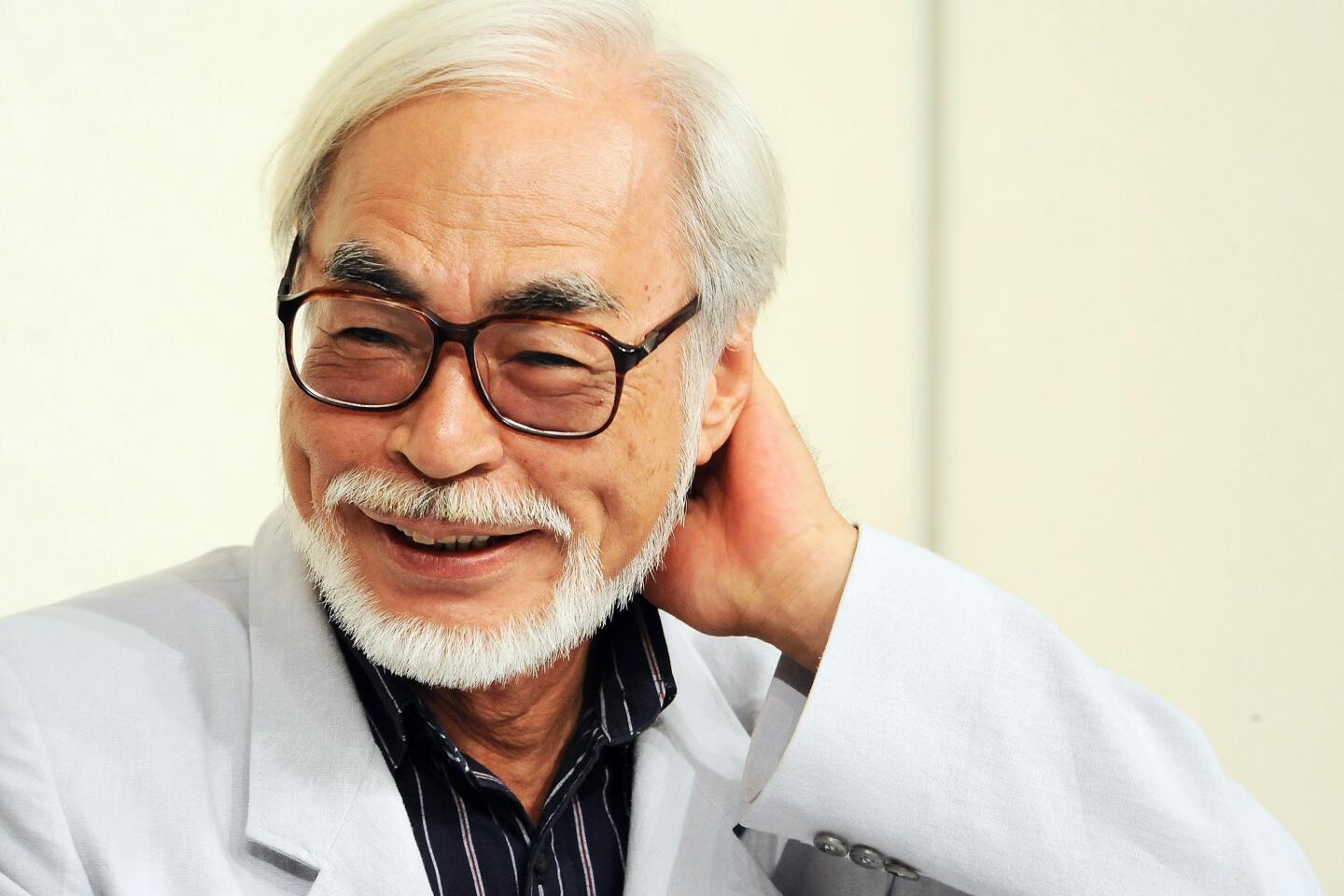

Tellingly, the soft-spoken, white-haired grandfather whose work inspired this social media frenzy doesn’t use a cellphone or the Internet — “It’s jarring and interrupts,” Miyazaki said — and he has practiced his craft for the last 50 years, wielding that most old-fashioned of tools, a pencil.

PHOTOS: Hayao Miyazaki, an animated icon

Now, as the world around him moves ever faster, Miyazaki has announced plans to slow down. The 72-year-old director says his latest film, “The Wind Rises,” will be his last.

“Everybody is younger than me,” he said, speaking by phone recently from his Tokyo studio through a translator. “They don’t understand what it’s like to be old. I’ve learned a lot of things by being 72, and what I’ve learned is that I don’t have a lot of time.”

“The Wind Rises,” which opened in Los Angeles on Friday for a one-week Oscar qualifying run in advance of a wider release next year, is a departure for Miyazaki. Normally, his family-friendly fantasies such as “Howl’s Moving Castle,” “My Neighbor Totoro” and Oscar winner “Spirited Away” are set in magical realms populated by wizards, witches and sprites. They’re often subtle paeans for pacifism and odes to nature built around strong and clever female characters.

“The Wind Rises,” by contrast, is set in pre-World War II Japan and tells the story of a real man, Jiro Horikoshi, who designed the Zero fighter plane. The film, which is based on a short story by Japanese poet Hori Tatsuo, depicts an era when Japan faced some of the same problems that have plagued the country in recent years, including a devastating earthquake and economic stagnation.

Miyazaki had just finished storyboarding a sequence of Japan’s 1923 earthquake, which set Tokyo afire, when the powerful 2011 temblor hit.

“I worked on sci-fi material before, imagining what would happen in the future, but when the earthquake happened two years ago, I felt, ‘Oh no, the actual reality of the world has caught up with me,’” he said. “When we could see the changes of the times, I didn’t feel I could make some fun fantasy.”

Miyazaki, whose father made rudders for the Zero planes, also shows the artistry that went into building the elegant but deadly aircraft, scores of which would ultimately end up attacking Pearl Harbor.

It’s an unusual choice of material for a self-identified pacifist, who stayed home from the Oscars when he won for “Spirited Away,” because, as he later told a Times reporter, “I didn’t want to visit a country that was bombing Iraq.”

“Jiro Horikoshi is also a pacifist,” Miyazaki said, explaining this seeming contradiction. “Because of the times he was living in, the only thing he was allowed to make was a fighter airplane. I can’t accuse my father or Horikoshi of doing the wrong thing when they had to live in such dangerous times.”

In Japan, where “The Wind Rises” opened in July, Miyazaki has taken his antiwar stance beyond the cinema. In June, he penned an essay objecting to the new prime minister’s plan to amend the country’s constitution allowing for the building of a full-fledged military. Some conservatives labeled him “anti-Japanese” and a “traitor.”

PHOTOS: Billion-dollar movie club

The sharp response surprised him. “I feel that there is something of a smell of war,” Miyazaki said. “I’m appalled at the outdated nationalism.”

The set-to is all the more remarkable given Miyazaki’s revered stature in his home country.

Years ago, John Lasseter was walking with the director near his studio in Tokyo when a group of schoolgirls saw Miyazaki and approached him. With his shock of white hair and broad smile, Miyazaki is instantly recognized there — Lasseter likens the director to one of his best-known characters, a grinning, cat-shaped bus from “My Neighbor Totoro.”

“He’s got the smile that is infectious. His cheeks rise up into his eyes,” said Lasseter, the chief creative officer of Disney and Pixar Animation Studios and a longtime friend and admirer of Miyazaki’s. “He’s so unassuming.”

Miyazaki drew little bunnies from “Totoro” on the schoolgirls’ hands, Lasseter said. “What is amazing to see is what he means to the people of Japan,” he said.

With his status also comes the burden of responsibility, particularly to the hundreds employed at his company, Studio Ghibli, including Miyazaki’s son, Goro, who directed Ghibli’s last film, “From Up on Poppy Hill.” The elder Miyazaki has said he hopes to leave some of that sense of duty behind in retirement, focusing instead on drawing his own manga (Japanese comic books) and producing short films for Studio Ghibli’s museum.

PHOTOS: Behind the scenes of movies and TV

“I’m just happy I don’t have to think about my next movie,” Miyazaki said. “I would rather go on my walks. There’s a nursery next door to my studio and I can hear children, which I like very much.”

Miyazaki is the best-known practitioner of the dwindling medium of hand-drawn animation, which seems likely to continue its long fade along with him.

He’s also unusual for the gentle tone of his films. Even “The Wind Rises,” about the building of war machines, has placid sequences of young Horikoshi setting paper airplanes into flight.

Looking back, Miyazaki said he has some regrets. He wishes he’d drawn the character of Howl in “Howl’s Moving Castle,” more “sharp, pointed and devilish,” for instance, but he wasn’t willing to take the artistic risk at the time.

“I’m mad at myself,” he said. “I did my best, given the circumstances. Even though I’m not satisfied with myself, I think I worked harder than others did.”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.