‘Lenny Cooke’ documentary follows basketball hopeful’s road to defeat

As unlikely as it seems, failure and obscurity can have rewards of their own. The new documentary “Lenny Cooke” follows its titular subject on the road to defeat. Or rather, the film explores how defeat can nevertheless lead to a triumphant confirmation of self.

The film, opening Dec. 13 in Los Angeles, chronicles the story of Lenny Cooke, a New York City basketball prodigy who in the early 2000s was ranked as the No. 1 high school basketball player in America. A drift of miscalculations, bad representation and fatefully bad decisions curtailed Cooke’s professional basketball career before it had even really begun. After declaring himself eligible for the 2002 NBA draft, he was passed over, falling into an obscure series of lesser-known teams and leagues in the U.S. and abroad.

The current “Inside Llewyn Davis,” in which the musician of the title is shown as his own worst enemy, was created whole-cloth by Joel and Ethan Coen, and it took another pair of movie-making siblings to bring Cooke’s story to the screen. New York City filmmakers Josh and Benny Safdie had never made a documentary before, and yet the indefinable appeal of Cooke fit neatly alongside the central characters of their eccentric fiction works, the ragamuffin scamp thief in “The Pleasure of Being Robbed” and the ill-equipped father of the semi-autobiographical “Daddy Longlegs.”

By turns charming, moody, electrifying and distant, Cooke is such an inscrutable character that it can seem as if the Safdies wrote him themselves. Structured chronologically, the film moves from grainy, outdated video formats to sleeker-looking contemporary footage, giving viewers both a sense of Cooke’s world while also leaving him a teasing enigma. It builds to a moment of unexpected grace, via some unconventional movie trickery.

“We love basketball, but we didn’t want to just make a standard boilerplate film that’s so easily centered around the sports aspect,” said Benny Safdie, 27. “And we realized, ‘OK, there is something else here, there is something outside of that world.’ It was off the court. You could see why he didn’t make it, not so much because of his basketball skills but in his personality and approach.”

“Here was somebody who was not a good basketball player, but the best. ... He could say he was the best at one point in his life,” said Josh Safdie, 29, on the phone with his brother. “He has the ultimate perspective on life, he’s been on top, the bottom and everywhere in between.”

PHOTOS: Holiday movie sneaks 2013

The project got its start in 2001 when Adam Shopkorn, then an aspiring filmmaker in his early 20s, wanted to explore the burgeoning phenomenon of high school players going straight to the NBA, leapfrogging their collegiate careers for a high-pressure world of multimillion-dollar contracts. (Shopkorn, credited as producer on the finished film, now works as an art dealer and curator.) It was then he began shooting with Cooke, following him on what seemed a sure-fire journey straight to the pros.

“I thought it would be really interesting to document that process over a two-year period. I was looking at it like I was going to find a guy who was going to do it successfully,” said Shopkorn, now 35. “And I wound up not having that guy.”

Cooke moved from Bushwick in Brooklyn to play for a high school in New Jersey before decamping for a time to Michigan. After Cooke wasn’t drafted into the NBA in 2002, he and Shopkorn fell out of touch and ( Shopkorn put the footage into a shoebox.

PHOTOS: Billion-dollar movie club

Having known the Safdies since childhood, he told them about the thwarted project after attending a 2010 “Daddy Longlegs” screening in New York. The brothers knew of Cooke’s story and, after giving the footage a look, they were intrigued. The trio reconnected with Cooke and picked up his story from there.

In a sense the Safdies got to meet Cooke twice, once through Shopkorn’s original footage and then again when they all met him in person. “We watched all of this footage and really got to know him,” Josh Safdie said. “And then we see him for the first time, and it was almost like I was meeting a parable.”

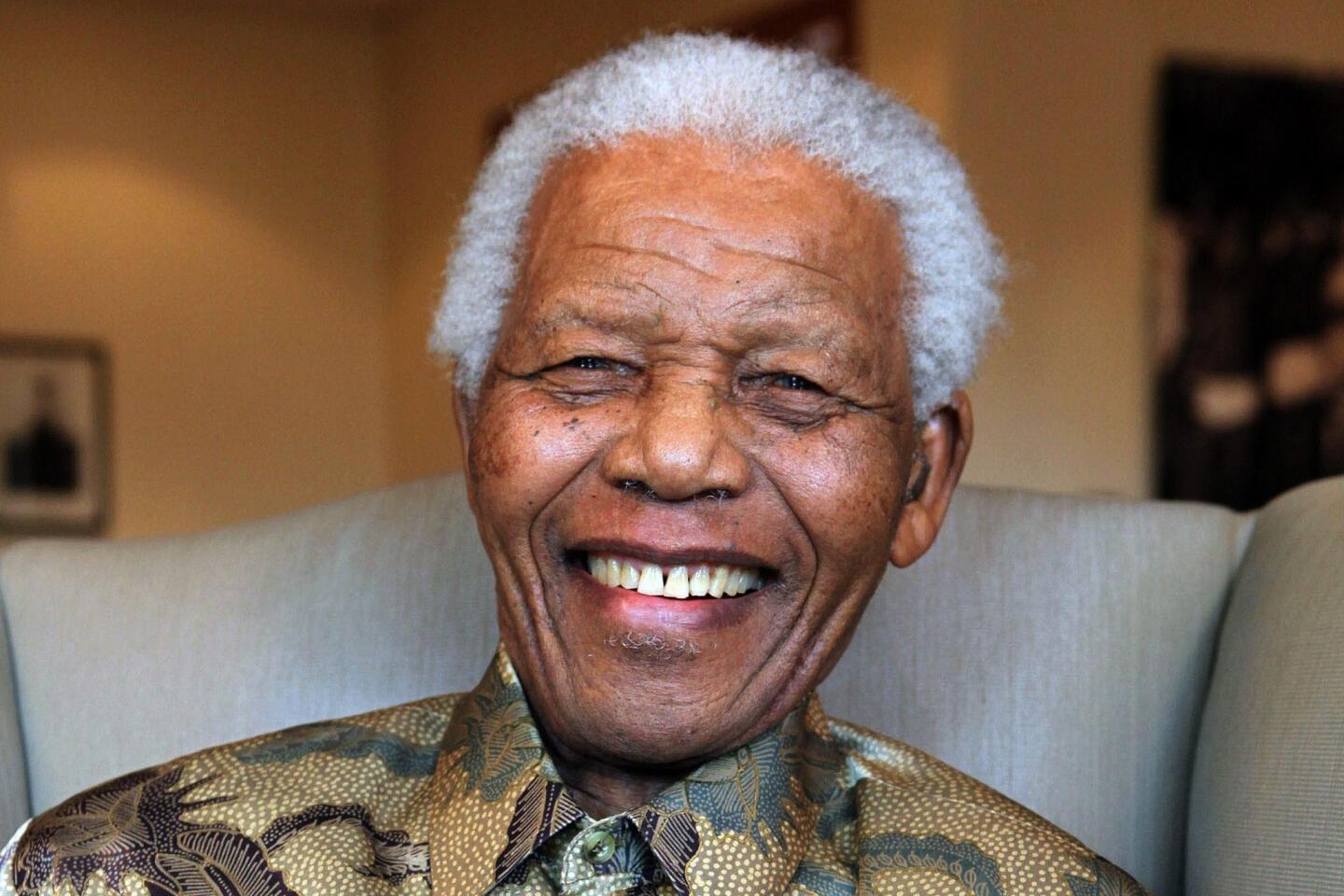

Cooke, now 31, lives in Virginia not far from Richmond. With his playing days behind him, he most recently has been doing some coaching and speaking to youth groups about his story. There have been years of struggle, and the footage captured by the Safdies with Shopkorn in more recent years finds him transitioning between ruminative anger and a hard-won equilibrium. In a scene at his 30th birthday party, Cooke wavers between playfulness and breaking down in tears.

PHOTOS: Celebrities by The Times

Chicago Bulls star Joakim Noah, credited as executive producer on the film, recently attended a screening in Chicago, as did Jahlil Okafor, currently considered the best high school basketball player in the country. Noah and Okafor were photographed alongside Cooke, and it is for a younger generation of student athletes that Cooke hopes the film has a cautionary effect.

“I don’t have any regrets,” Cooke said on the phone, “because of the simple fact that the decisions I made and the things I did, I did those things because I wanted to do them. I didn’t do it because anybody pushed me to do anything. I made all of my choices on my own.”

The film builds to an astonishing moment when, through crafty editing and shooting Cooke in front of a green screen, he is allowed to speak directly to his younger self.

“We didn’t want to impose ourselves on the story, and it’s weird that the result of that is this crazy special effect which is kind of the ultimate imposition on the film,” Benny Safdie said. “But it doesn’t feel like that, it feels like, of course, he can go back and talk to himself.”

PHOTOS: Greatest box office flops

“We wanted the movie to be from Lenny’s perspective,” Josh Safdie said. “We didn’t want to tell you why we think he did what he did. So we had him tell us.”

For Cooke, shooting the scene was a deeply emotional moment, the likes of which he had never experienced before. “Those things I say now, I never said that to myself,” Cooke said. “Looking back on it, I’m able to explain to these kids now the things that I didn’t have explained to me when I was 16, 17, 18 years old.”

The scene takes the film to the place the Safdies ultimately wanted it to go, giving a deeper meaning to Cooke’s travails and finding a resolution that uses the past to look ahead.

The moral of Cooke’s story, if there is one, is bigger than any single game or moment. As Cooke himself says, his story is about “not just basketball but life in general.”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.