Review: ‘The Young Karl Marx’ explores the unexpected early days of a revolutionary historical figure

Not to get too dialectical about it, but the title “The Young Karl Marx” sounds like a contradiction in terms.

We’ve all seen the image of the venerable Karl Marx, the earth-shattering theorist with the full white beard, the man whose massive, three-volume “Das Kapital” and pamphlet-sized “The Communist Manifesto” upended Western society and inspired revolutions worldwide.

For the record:

4:15 p.m. Feb. 22, 2018An earlier version of this review reversed the names of the actors playing Russian anarchist Mikhail Bakunin and activist Wilhelm Weitling. Ivan Franek plays Bakunin and Alexander Scheer plays Weitling.

But what’s with the “young” part, which brings to mind turbulent emotional dramas rather than trenchant economic theory? Whatever else you think about Marx and his ideas, it’s hard to imagine him as hot-blooded and young.

Director and co-writer Raoul Peck, as it turns out, not only understands those contradictions, he is committed to embracing them, which is what makes “The Young Karl Marx” the audacious, engrossing film it is.

“Young Karl Marx” is a long-gestating project for Peck, whose commitment to both social justice and serious cinema is evident in everything from 2000’s “Lumumba” to last year’s brilliant, Oscar-nominated and BAFTA winning James Baldwin documentary, “I Am Not Your Negro.”

Working from the considerable correspondence the key participants left, Peck and his veteran collaborator Pascal Bonitzer (who wrote “Lumumba” with him) want to show Marx and his close collaborator Friedrich Engels as flesh and blood as well as politically committed.

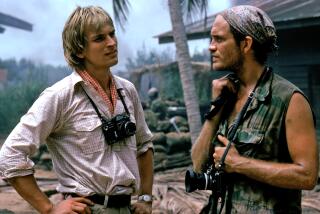

Played by top German actors August Diehl (a Nazi officer in “Inglourious Basterds”) and Stefan Konarske, Marx and Engels deal with relationships and wives and all manner of emotional entanglements that share time in their lives with theoretical thinking and determined action.

None of this means that the era’s intense political philosophizing and maneuvering are given short shrift. As Peck writes in a director’s statement, as a university student in Germany he “acquired knowledge of and about Karl Marx’s actual work — rather than the dogma.” So, against all expectations, “Young Karl Marx” makes this kind of brainy content bracing and dramatic.

This is the kind of film where we not only hear about the Young Hegelians, we meet some of them verbally jousting with Marx in a newspaper office in 1843 Cologne.

We’re gradually introduced as well to key figures like France’s Pierre-Joseph Proudhon (Dardennes brothers regular Olivier Gourmet), who pioneered the idea that property was theft; the celebrated Russian anarchist Mikhail Bakunin (Ivan Franek); and the charismatic activist Wilhelm Weitling (Alexander Scheer).

“The Young Karl Marx” opens with a typical mixture of theory and vivid dramatic action, as marauding Prussian soldiers on horseback attack impoverished peasants for “stealing” the dead tree branches off a forest floor, while Marx in voice-over savagely condemns the assault.

“You have erased the difference between theft and gathering,” he thunders. “The people see the punishment but not the crime. And as they do not see a crime when they are punished, you should fear them, for they will take revenge.”

As energetically played by Diehl, Marx is a whip-smart firebrand whose passion and energy are palpable, an arrogant polemicist who doesn’t care who knows it.

Tired of arguments without facts to back them up and feeling “I’ve had enough fighting with pins, I want a sledgehammer,” Marx evades his political difficulties at home and, though funds are almost nonexistent, moves to Paris with his wife, Jenny, and their young child.

The daughter of a wealthy aristocrat from the Prussian city of Trier and a formidable person in her own right, Jenny is brought to full and absorbing life by Vicky Krieps, who went head to head with Daniel Day-Lewis in “Phantom Thread” and keeps her costars on their toes here.

We are also introduced early on to Engels, a fellow political radical who chafes at being the son of the wealthy owner of a Manchester textile factory.

Engels is attracted, both romantically and politically, to Mary Burns (Hannah Steele), one of the most outspoken of his father’s workers and someone whose access to laborers helped Engels in the writing of his groundbreaking “The Condition of the Working Class in England,” published in 1845.

The film’s central “When Karl Met Freddy” moment happens in Paris, and, in truth, the two men, both easily offended, are put off by each other at first.

But as we eavesdrop on the meeting, the enormous admiration each has for the other’s work, and the realization that they see the world the same way, brings them together both as friends and collaborators.

Both Marx and Engels not only believed in scientific analysis based on facts but also were committed to direct action as opposed to the kindness and fraternity of some of their peers, all of which leads to the writing of the “Communist Manifesto” that is the film’s culmination.

“The Young Karl Marx” closes with a snappy historical montage that shows some of the events theorizing led to, but a weighty pro and con is not on this film’s mind. The focus is on two young men and how they happened to change the world.

------------

‘The Young Karl Marx’

Not rated

Running time: 1 hour, 58 minutes

Playing: Laemmle’s Royal, West Los Angeles; Playhouse 7, Pasadena

See the most-read stories in Entertainment this hour »

Movie Trailers

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.