Review: Todd Solondz’s ‘Wiener-Dog’ puts humanity in a tragicomic cage

Nothing softens up a hard-hearted auteur quite like the presence of a beloved animal. The Coen brothers demonstrated this conclusively a few years ago with “Inside Llewyn Davis,” an exquisite ode to loserdom that was brightened, and at times upstaged, by a winsome orange tabby cat. And even that most snappish of cinematic eminences, Jean-Luc Godard, seemed freshly energized when, while making his 3-D extravaganza “Goodbye to Language,” he had the wisdom to turn the camera on an adorable pup named Roxy Miéville.

“Wiener-Dog,” Todd Solondz’s barbed and beguiling canine odyssey in four parts, may be the exception that proves the rule. A writer-director known for his confrontational, harshly funny dissections of American middle-class life, including “Happiness” (1998), “Storytelling” (2001) and “Dark Horse” (2011), Solondz is not entirely immune to the charms of the beautiful brown dachshund he’s placed front and center here. But he never lets those charms distract him from the dog’s chief purpose, which is to bear witness to a rich and appalling spectrum of human idiocy, misery and self-absorption. She is both man’s best friend and a stark reminder that mankind is its own worst enemy.

If that sounds familiar, it’s because “Wiener-Dog” is effectively a jaundiced riff on “Au Hasard Balthazar,” Robert Bresson’s 1966 masterpiece about a donkey whose short, sad life illuminates the tragedy, the absurdity and the occasional sublimity of earthly existence. Solondz doesn’t do sublimity, but he’s a dab hand at the other two. At his best, and in the best moments of this thorny and uneven new work, he is capable of making tragedy and absurdity seem almost indistinguishable.

The dachshund’s first master is a 9-year-old boy and cancer survivor named Remi (Keaton Nigel Cooke), who names her Wiener-Dog. (It’s unimaginative but far better than what her future owners end up calling her.) Remi loves his new pet, but his miserable parents (Tracy Letts and Julie Delpy) don’t exactly share his affection, especially after Wiener-Dog ingests a granola bar and relieves herself all over their attractively furnished suburban home. Solondz films the aftermath in an extended tracking shot set to Debussy’s “Clair de Lune”; had he pushed the Bresson theme further, he might well have titled this chapter “Diarrhea of a Country Pooch.”

A medical detour sends our four-legged heroine off on her next adventure, now in the company of a lonely veterinary assistant (Greta Gerwig) and her junkie-drifter friend (Kieran Culkin) as they head out on a road trip to Ohio. Sharp-eared Solondz devotees will recognize both these characters from his 1995 breakthrough feature “Welcome to the Dollhouse,” with Gerwig playing an awkward, grown-up version of that film’s protagonist, Dawn Wiener. It’s not the first time Solondz, a playful formalist, has reintroduced past characters in the guise of completely different actors (see “Life During Wartime,” his underrated semi-sequel to “Happiness,” or “Palindromes,” which actually kicked off with Dawn’s funeral). In his cinematic universe, the faces of human despondency are more or less interchangeable.

That sense of resignation increasingly infects Solondz’s screenplay, which concerns itself less and less with the specifics of how Wiener-Dog passes from owner to owner, and more and more with the cruelty of life’s inevitable downward spiral. After a cross-country intermission that affords the film’s sole moments of unalloyed pleasure, Wiener-Dog is the companion of Dave Schmerz, a failed Hollywood screenwriter and widely derided film-school professor played to misanthropic sad-sack perfection by Danny De Vito.

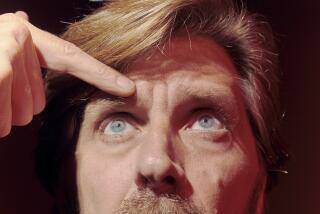

In an interview with The Times at the 2016 Sundance Film Festival, Todd Solondz talks about his new film “Wiener-Dog” and what he learned from his childhood pets.

Wiener-Dog’s last and most indelible adventure involves a cranky shut-in (Ellen Burstyn), who pays little heed to either the dachshund or the sudden arrival of her talkative granddaughter (Zosia Mamet), paying one of her irregular visits to ask for money. In juxtaposing Mamet’s pathetic prattling and Burstyn’s cold-shoulder routine, Solondz somehow arrives at a piercing vision of two women in a state of shared yet unbridgeable despair. It’s the only one of the four stories that seems to invite the question: How did these people get here?

An answer of sorts is provided by the film’s ghostly penultimate sequence, which also offers a vivid showcase for the richness and subtle saturation of Edward Lachman’s reliably brilliant cinematography. The juxtaposition of formal beauty and surpassing human ugliness is hardly the least of “Wiener-Dog’s” numerous internal contradictions, some of which are more resolvable than others. More than ever, his attitude toward his characters seems an irreducible mixture of pity and contempt, and even his most juvenile attempts at outrage are complicated by eerie undercurrents of emotion.

There’s no denying, for example, that Remi’s mother is a complete horror show, never more so than when she’s telling her son a hideously inappropriate cautionary story about canine rape and unwanted pregnancy. But how to account for the tremors of feeling beneath Delpy’s perfectly judged comic delivery? For that matter, should we take heart at the fact that a husband and wife with Down’s syndrome (played by Connor Long and Bridget Brown) are easily the happiest, best-adjusted characters in the picture — or should we take offense at the way Solondz links their reproductive capabilities to those of the dachshund?

Whatever the answers to these questions, the director at least has the integrity to subject himself to similar scrutiny. For all the relish with which Solondz sends up both the Hollywood studios and the independent film community that has supported him over the years, Dave Schmerz is not the character he most seems to identify with. That would be an artist who goes by the name of Fantasy (Michael James Shaw), whose work, we later see, consists of meticulously reproduced imitations of life, trapped under glass and displayed for all to see. The final image could be Solondz’s acknowledgment of the diorama-like limitations of his own art, or it could just be his latest epitaph for all humanity: Welcome to the doghouse.

------------

‘Wiener-Dog’

MPAA rating: R for language and some disturbing content

Running time: 1 hour, 33 minutes

Playing: In limited release

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.