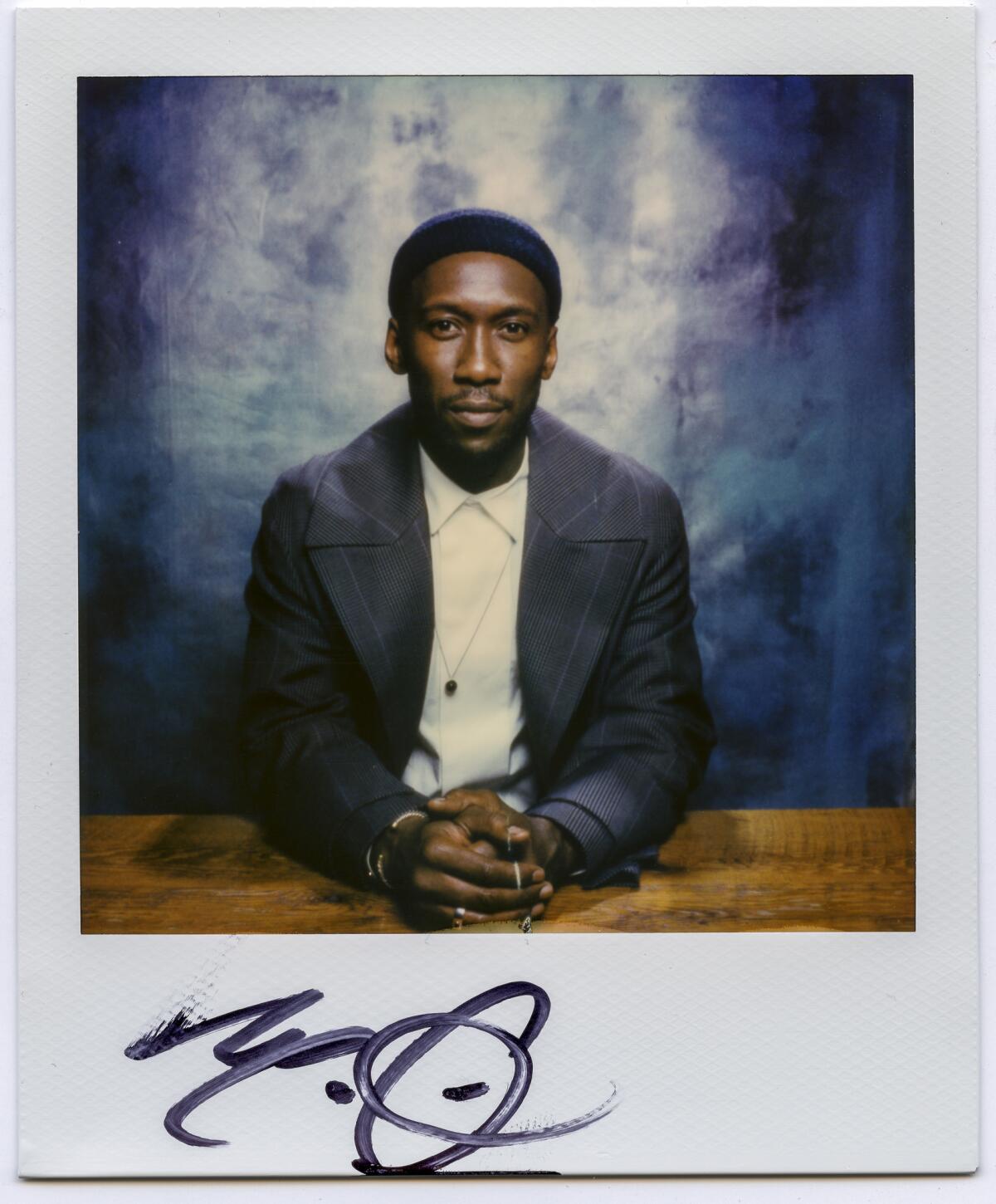

Mahershala Ali channels the pain of frustrated black artists in ‘Green Book,’ but sees Hollywood’s changing attitude

Roughly halfway through “Green Book,” about one of the unlikeliest friendships of the civil rights era, Jamaican piano prodigy Don Shirley (Mahershala Ali), explains to his Italian American driver and companion, Frank “Tony Lip” Vallelonga (Viggo Mortensen), that though he’s found success playing popular music, he was trained for the classical stage.

“Trained?” says Vallelonga. “What are you, a seal? People love what you do. Anyone can sound like Beethoven or Joe Pan or them other guys you said. But your music, what you do, only you can do that.”

“Thank you, Tony,” Shirley says patiently. “But not everyone can play Chopin, not like I can.”

The scene, one of the film’s most poignant insights into the musician’s conflicted feelings about his identity and legacy, was not always written that way.

“Dr. Shirley used to just say, ‘Thank you, Tony,’ and that’s it, that’s the scene,” recalled Ali over lunch in Los Feliz. “Like, ‘I appreciate it, you’re right. People love my music and despite the racism, what I became as a result is alright, I’m cool with it.’ And that scene always ate at me. It just didn’t ring true to me as a black person. It felt like what I would call a ‘TV moment.’”

After watching Nina Simone’s Netflix documentary “What Happened, Miss Simone?” Ali was able to pinpoint just what it was that bugged him about the scene and brought it to director Peter Farrelly.

“I spoke at length with him about Nina Simone in that, as much as we love and appreciate her music, she didn’t become who she wanted to become, she became who she was allowed to become,” he said of the legendary dive-bar chanteuse, who’d originally had designs on being a classical pianist.

Nina Simone lived and died not being what she wanted to be. I think that that is true for so many black artists. And Don Shirley was the same way.

— Mahershala Ali

“The fact is, as a person, as an individual knowing and feeling the creativity within herself, Nina Simone lived and died not being what she wanted to be. I think that that is true for so many black artists. And Don Shirley was the same way.”

“Green Book,” which is now playing nationwide, is already being floated as a potential best picture nominee after claiming the Oscar-predictive People’s Choice Award in its world premiere at the Toronto International Film Festival. Ali’s portrayal of the emotionally tortured Shirley is all but guaranteed to earn him a supporting actor nod. If so, it would mark his second Academy Award nomination, after a breakout turn in Barry Jenkins’ dazzling “Moonlight,” for which he took home the trophy in 2016. But awards consideration, though appreciated, couldn’t be less of a driving force for the actor.

“We’re not going into it like, ‘OK, so when we look at the Oscar contenders, these films need to have these boxes checked,’” he said. Rather, the 44-year-old just wants to continue taking on roles that are different from those he’s played over the course of 20 years in the industry.

“For me, it’s about the diversity of my experience as an actor,” he said. “I’m just constantly looking for something that feels appropriate for me at the time. I don’t ever want to do something I’ve already done, I’m not interested in that at all.”

Though Farrelly calls him an “unbelievable actor,” the director was hesitant to cast Ali because of the tonal difference between the outwardly powerful drug-dealer Juan in “Moonlight” and the more delicate, internal restraint of Shirley.

“He was such an imposing figure in ‘Moonlight,’” said Farrelly. “He was big and strong and really a force. And Dr. Shirley is not that. I thought maybe Mahershala might be too big a figure for this film, but when I met him, and he talked about who this guy was, he quickly became him. It was such an impressive performance.”

“This is going to sound like B.S., but it was an honor and a pleasure [working with Ali],” said Mortensen. “For me, the foundation of good acting is always good reacting. I’m looking at his face and there are all these incredible, minute, beautiful reactions. Like, so precise, his work. It was really difficult to keep a straight face because he was so hilarious and getting perfect timing.”

“What an incomparable talent the guy is,” Farrelly added. “I’ve had a couple people point out to me, ‘Boy, that scene out in the rain, that’s an Oscar scene.’ I said, ‘Well, not really, not to me.’ The Oscar scene is the entire rest of the movie when he is telling us how he feels and it’s all inside him but we’re feeling what he’s feeling in a very, very nuanced performance. That’s the tough acting.”

The painstaking performances of the two leads elevate the film’s fairly simple premise: In 1962, Shirley, a distinguished pianist, prepares to embark on a concert tour that will take him through the Deep South. He knows he needs to hire some muscle, which is where Lip comes in, a racist bouncer who just lost his job at Manhattan’s Copacabana nightclub. (The title “Green Book” came from “The Negro Motorist Green-Book,” Victor Hugo Green’s guide for African Americans to find safe accommodations in segregated Southern towns.)

Over the course of the trip, Shirley and Vallelonga become friends, a dynamic which has earned the film comparisons to “The Odd Couple” and deemed a “reverse ‘Driving Miss Daisy,’” a description that rankles Ali.

“There’s absolutely no such thing, it’s impossible,” he said. “Because in either scenario, if you make the white person the driver or if you make the white person the passenger, the white person is still free in society. That’s like saying, ‘Now the white person is black in this scenario.’ The white person is never black in any scenario. The switch just doesn’t work.”

He also rails against the notion that the film employs cinema’s longstanding “white savior” trope.

“It’s unfair to say we can’t see a movie in this time where a white guy does something that helps a black guy,” he said. “I think that’s kind of stupid, honestly. Because then it always has to be the black person saving or doing something that is heroic for the white person because we’ve got to balance out 100 years of cinema.”

Ali was immediately sold on the opportunity to play a character as dynamic and rich in texture as Shirley.

“Don Shirley was exceptional ... I haven’t seen him on film,” he said. “The opportunity to step into the shoes of a man with that much complexity — who spoke eight languages, was a piano prodigy, had affluence and was successful and connected — even though he’s in an environment that limits his freedom, I think that he has more power than any other black character that I’ve personally seen in a pre-civil-rights-era film or story.”

Despite being doubled in the film’s concert scenes by composer and pianist Kris Bowers (who also provides the score), Ali took months of piano lessons to prepare for the role. (“I wanted Pete to be able to use as much of me as possible,” he explained.)

The lessons served a dual purpose, also offering the actor a better understanding of how piano mastery might have affected Shirley’s sense of self and belonging.

“I feel like the mastery of that instrument impacted everything else he did in the world: how he picks up a glass, his feelings about the whiskey being left on the piano, how he throws the chicken bone,” he said. “I felt like I needed to be on that piano to understand how to move throughout the rest of the piece.”

Echoing the stick-straight posture of a pianist proved difficult (“It hurt, it was uncomfortable,” he said. “I think my muscles started changing after about a week.”), but pretending to play the piano convincingly posed the biggest challenge, especially because he wasn’t told in advance what piece of music they were scheduled to shoot.

“It was really hard to rehearse the musical parts because I always wanted to make sure that I was in the right place on the piano,” he said. “And also being conscious of what the left arm is doing, what the right arm is doing, where it is on the piano at what time. Because whatever they decided to use, my body needed to be doing the right thing. I’m not trying to be a distraction to the movie, that was going to break my heart.”

Since he took home the Oscar for best supporting actor in “Moonlight,” Ali says his career has seen a significant change, most notably via offers for lead roles rather than supporting ones. But at home, he has yet to unpack the trophy from its protective casing.

“It’s not even out right now,” he said with a laugh. “We just moved so it’s been bubble-wrapped for like six months because we were doing some renovating. But I’m going to break it out.”

Though they both grapple with themes of identity and self-perception, one of the most glaring contrasts between “Moonlight” and “Green Book” is the way each film and filmmaker tackles the subject of race.

“I think Barry approached race without ever speaking it,” said Ali. “This film tells you what it is, so naturally in the marketing, in the conversations about the piece, they are more consciously addressing race. But then also I think the major difference is the responsibility I have to speak on behalf of the film because of being one of the leads.”

That sense of responsibility inspired him to speak out about a contentious moment that occurred when Mortensen came under fire for using the N-word in a discussion of how times have changed since the “Green Book” era during an awards season Q&A. Acknowledging the “lack of awareness” that contributed to the incident, Ali was able to find the silver lining in what he calls a “teachable moment.”

“There’s nothing in me that believes that Viggo is racist,” he said. “And even in him using the word, it wasn’t intended to be racist, if anything it was the opposite. It’s sort of a perfect moment in that it’s actually exactly what the film is about — awareness.

“Anytime a non-black person says that word, a little bomb goes off,” he continued. “What Viggo said, it’s not about it being politically incorrect because he was well-intended, but within [the black] community, that’s a word that we get to figure out how and when we want to use it, if we want to use it at all. That’s something that we as a community need the time and space to have a conversation about.”

“We spoke and we are better friends than ever now,” said Mortensen of what happened following the Q&A. “We understand each other and I’m relieved because we started out really tight. Sometimes a friendship can get tested and if you’re lucky, you can come out on the other side even better and that’s actually what happened. He’s a big man and he has a big heart and I love him.”

Though it only makes sense that conversations about race dominate the press run for “Green Book,” Ali says it’s a nagging point of discussion no matter what project he’s promoting.

“When I go and do these press junkets ... I always spend a good 30% to 40% of the time talking about race,” he said. “You spend so much time as a black artist speaking about the black experience that it’s almost like the writers are conditioned to speak to me on those terms. Which is cool, but they still don’t necessarily reserve enough space to really get into the nuances of the work.”

He takes issue with the tendency for black art to become tangled up in clunky conversations about race and representation, rather than being lauded for its merits the way white art is.

“People really lean towards talking about the cultural relevance,” he said. “So much time is spend on clapping and celebrating the feat or the achievement of a black project doing well and black people being multidimensional. So much time is spent on ‘Wow! A multidimensional thug in “Moonlight”!’ I appreciate it, but what about the work is transformational?”

Despite this, he allows that Hollywood is much more open to diverse stories and storytellers now than in the recent past.

I think Hollywood is always ready to embrace a new vein, a new anything that’s going to help expand storytelling that is also economically beneficial.

— Mahershala Ali

“I think Hollywood is always ready to embrace a new vein, a new anything that’s going to help expand storytelling that is also economically beneficial,” he said. “If Hollywood is making money off of something, then they want to figure out ways to tap into that. And for us, the positive thing is that we get to tell our stories how we want to tell them.”

He points to the HBO series “Random Acts of Flyness” and “Insecure” by way of example.

“By no means is Issa Rae’s show about race, but it doesn’t escape it,” he said. “I think the creatives are arguing the value of Hollywood not beating people over the head with race, but telling stories that are more of a reflection of how black people experience race. Which is not the N-word all the time, it’s the lack of opportunity or it’s the look of ‘Do you belong here?’ It’s not just about doing ‘Malcolm X II’ or ‘Selma: The Day After,’ there’s other, more contemporary ways to approach it.”

Up next, he joins the network’s third season of “True Detective,” following in the footsteps of Matthew McConaughey and Woody Harrelson in the titular role, another part that will likely entangle him in more conversations about the intricacies of race in America.

“That’s just the life of a black artist,” he said. “Because traditionally, there’s just not enough of us, so we have to look to those who have a platform in some regard to reserve a slice of that experience to be leaders. And it’s not easy, there’s a lot of pressure, no doubt. But I don’t believe God gives you anything you can’t handle.”

follow me on twitter @sonaiyak

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.