From the Archives: In the kingdom of the clown: Jerry Lewis remasters his life’s work

Film legend Jerry Lewis died Sunday at 91 in Las Vegas. Contributor James Verini spoke to Lewis in 2005 as he prepared to make a comeback after being away from Hollywood for decades.

Jerry Lewis, the comedian, misunderstood director, one-time movie star and crusader for ill children, first came to this city sometime in the late 1940s because he and his new partner, Dean Martin, were booked to perform at the Flamingo. He lost so much money gambling it took him 3 1/2 years to pay it back. Nonetheless, he called Las Vegas “the most joyful city in the world.” He’s now lived here for 25 years.

“I came to get away from the traffic in L.A.,” Lewis says. “Now we have it here.” He’s just answered the door of his unassuming red brick two-story house and does not seem thrilled to be letting a reporter in, though the appointment has been set for weeks. After years of battling serious illnesses, his health is fragile, though the face is still childlike, even in its fleshiness. Lewis, who is 78, is recovering from a cold and trembling visibly. Over his clothing he wears a black kimono-like gown, kimonos and kimono-like gowns being leisure-wear favorites of his. (He spent an entire movie, 1958’s “The Geisha Boy,” in one.)

Absent from Hollywood for 20 years, Lewis, it seems, is preparing to make something of a comeback. He claims to be considering a number of scripts to direct or act in or both. “They want me to star,” he says, not explaining who “they” are.

He’s planning a series of shows at the Orleans Hotel and Casino, where he returns triumphantly every few years for a week of schtick and sentimental standards. This month, he will be honored by the Los Angeles Film Critics Assn. (despite his well-publicized comments to The Times in 1981 that American film critics are “whores”).

And he’s reissuing his life’s work on DVD. Through a highly unusual deal he struck with Paramount Pictures in the 1960s, he has recently reacquired the rights to nearly all of his movies. Ten have just been released: “The Bellboy,” “Cinderfella,” “The Patsy,” “The Disorderly Orderly” -- just saying the titles, Cuban Missile Crisis radio bulletins and the screams of Beatlemania come to mind. Twenty more are on the way, including most of the titles from his years with Martin.

The rooms of Lewis’ Las Vegas house speak to the man -- part cerebral artist, part clown. They’re brimming with books, CDs, videocassettes and other interesting ephemera but also with overstuffed furniture, cheap tchotchkes and shelves full of porcelain animal figurines. Lewis’ study faces a large backyard and a pool with a fake mountain jutting from its deck that looks like a set piece from a Siegfried and Roy number. It was built for his 12- year-old daughter, Danielle.

This is not the first time I’ve met Lewis. I’d first gone to see him on the eve of his 39th Muscular Dystrophy Labor Day telethon, a month before. Actually, it would really be something more like his 50th -- the first broadcast was in 1955 -- but Lewis likes to start counting with 1966, when the telethon went national. Lewis has an eerie memory for dates. He remembers to the hour his first performance at the Copacabana, the first time he met John F. Kennedy, seeing his first bad review.

It was a muggy Saturday morning on the CBS studios lot, and Lewis was sitting behind a desk in the back of a makeshift office -- one of several occupied by his huge telethon staff, his huge family and countless handlers, friends and sycophants -- in short, brown shorts, a windbreaker and soft black loafers. He wore large red reading glasses and swigged from a can of Diet Sunkist orange soda. His crest, the famous laughing Lewis caricature in profile -- cleft chin jutting, crazy hair -- was everywhere.

He struck a more endearing figure that day. He was spry and quick on his feet when he deigned to stand, and his hair was still thick and well-Brylcreemed, though no longer jet black. He was quick with a deadpan stare or a whine of mock glee, and every few minutes he picked up his new Nikon digital camera and snapped someone or something.

“Every great film director is an avid photographer,” he said.

All of the company and the pressure animated him. Lewis is the type of person who is not drained but invigorated by people, so long as enough of them are around. The more the better.

But he was nervous too, and with good reason. A bomb scare at LAX had just shut the airport down, and several of his acts, as well as yet more friends -- the telethon is a yearly reunion of sorts for Lewis -- were stranded in various parts of the country. The hurricanes in Florida had prevented firefighters there from raising money and knocked out television and phone lines.

“I’m the backup act,” Lewis said. “My producer just asked me if I can stall for three hours. I said, ‘Oh, sure, I can do that on hisses alone. Boo! Hiss! Get him out of there! Move the Jew out!’ ”

A force for years

Lewis began performing on the vaudeville circuit in his native Newark, N.J., at age 5, was the most popular comic in America by 25 and had a 14-picture deal with Paramount at 32.

He was for nearly two decades, from the late 1940s to the mid- ‘60s, The Kid, a wunderkind, one of the biggest things in show business, capable of not only starring in but writing and directing hit movie after hit movie, of headlining TV shows, of cutting a top- selling album of straight-ahead hits. He was the embodiment of the frenetic anxiety of postwar urban life, and he and Martin were almost preternaturally suited to each other.

People lined up around blocks in the snow at 4 a.m. to see their club act. Bing Crosby was so scared of them he once walked off the set of his own TV special for fear that Lewis would rip his toupee off. Lewis and Martin broke up in 1956 (they did not speak again until 1976, when Frank Sinatra brought a tipsy, slightly dazed Martin onto the telethon) after which Lewis proved himself a solo virtuoso and an intellectual among entertainers, admired not only by Cahiers du Cinema but the likes of Orson Welles and Woody Allen. He taught at the University of Southern California film school, and in 1971 he penned “The Total Film-maker,” a collection of his lectures.

He has been a pariah, an elder statesman, an enigma, an inspiration (Jim Carrey cites Lewis as his greatest influence).

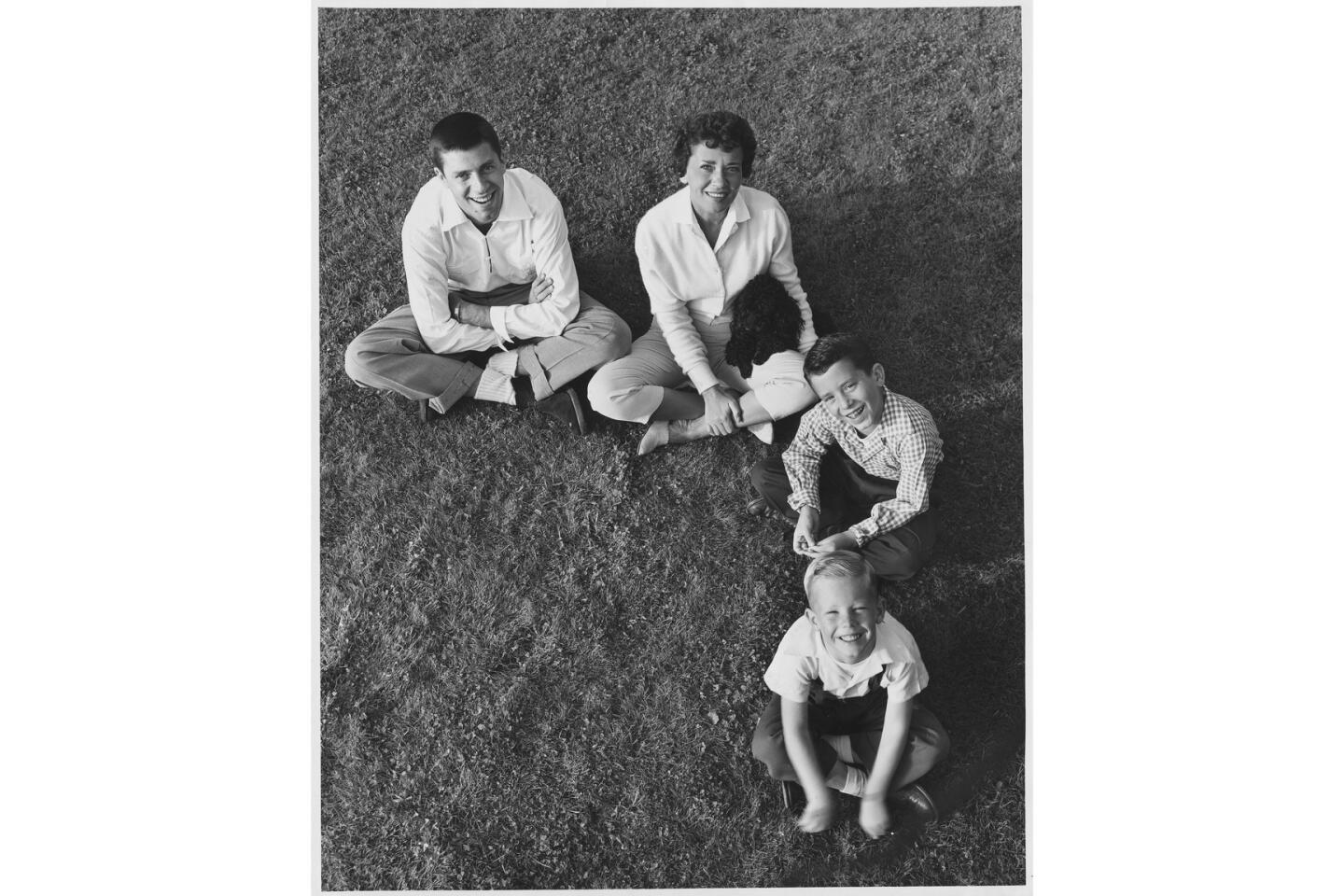

Now, in his autumn years, Lewis’ favorite activity seems to be holding court. On the CBS lot, he demanded hugs and kisses from his endless intimates -- including seven children, eight grandchildren and two great-grandchildren -- and offered tight handshakes to new acquaintances. He still lapsed into bits of the Heeeeello Laaaady extended-vowel shrillness.

“Heeere’s my daughter!” he exclaimed as Danielle bounced over, a shy friend in tow. “Give me a kiss -- a good one!” With an air of patient but juvenile regality, like a precocious l’enfante roi -- maybe that’s why the French love him so much? -- Lewis had equal time for everyone who came into the trailer. And they didn’t stop coming.

“James Kaplan, good mooorning, my friend, how are you?” he said as the New Yorker writer, who was co-writing a history of Lewis’ years with Martin, stepped in. He fixed Kaplan with a stare and then, as though lifting a rabbit from a hat, tore his reading glasses asunder. Kaplan looked quizzical. The frame, it became apparent, was joined by a small magnet at the bridge.

“Heeeeee!” Lewis squealed, delighted.

A deferential tailor approached with a handful of oversize black silk bow ties.

“What’s your name?” Lewis asked him, after he’d marked off his favorite specimen with a large red pen.

“Arturo,” the tailor said.

“Thank you, Arturo,” Lewis said, meaning it, rising to shake his hand.

He handed someone a joke-autographed vanity shot of Adolf Hitler. (Pictures of Hitler and Eva Braun seem to come up a lot with Lewis.) “This is the way I work,” he said, in an aside. “Somebody’s over here. Then there’s this thing here. Then I remember that other thing.” Lewis’ comedic rhythms, on the eve of 80, were still expert. This is no small feat for someone who’s been in the business as long as he has, who came up in Hollywood’s most debauched decades (Martin, who died in 1995, was a shell of a man by his mid-70s; Sammy Davis Jr. died at 65), who used to be a chain smoker and for much of his adult life had a nasty Percodan habit (the result of a lifetime of pratfalls, including a particularly bad one he took on “The Andy Williams Show”).

It was especially impressive in the case of Lewis, who lately had suffered enough illness to warrant his own telethon. In the early 1990s he was diagnosed with prostate cancer, then diabetes and not long after that contracted meningitis while performing in Australia. Having bettered those, in 2001 he was told he had pulmonary fibrosis. It was treated with the drug prednisone, which blew Lewis’ body up to an unsightly degree. In the last year he’s trimmed considerably, though he is fleshier than he’d like.

Partly because of his health, Lewis has limited his public exposure greatly in the last 10 years, acting in a few critically acclaimed but barely seen movies and doing the occasional guest spot on TV. He appeared in “Damn Yankees” on Broadway in 1995. Though he sunk a good deal of his personal fortune into a series of flops and bad business ventures in the 1970s and ‘80s (even investing at one point in a chain of Jerry Lewis movie theaters that never opened), he’s made much of it back. In 1993, he sold the remake rights to “The Nutty Professor” to Universal for $1.4 million and received a percentage of the profits. He’s sold the rights to several other films as well. He does corporate and college lectures, motivational speaking and promotes the pain-treatment company Medtronic.

Lewis has not taken a single year off from the telethon. He begins production meetings in early January, flying from Las Vegas, where he spends most of the year, or San Diego, where he keeps his boat, Sam’s Place (named for his wife; it is his second marriage), to the MDA headquarters in Tucson.

Asked why he does it, he was curt.

“I was personally involved with a dystrophic child. I’ve never ever told the real reason I do it. The important thing is that I do it, not the why. So enough about that.

“They told me I was nuts. They said, ‘You’re gonna ask people on television to give you money for kids? Are you prepared to humiliate yourself?’ But now I sit here with you $1.9 billion later, and I say, ‘I was right.’ ” Like many comics, Lewis is obsessed with numbers. He recalled exactly how much his first telethon raised: $600,000. How long former “Tonight Show” co-host Ed McMahon has been his emcee: 37 years. When he wrote his first bit: age 11.

He also remembers grudges, particularly it seems with journalists. Amid the last-minute chaos in the trailer, he found time to pull from his hulking metal briefcase a photocopy of a Daily Variety review of one of his stage acts and read from it.

“ ‘Lewis has plenty of know-how on selling a punch line, but this just isn’t his spot....’ Now understand something. I did a record act -- I never spoke. There were no punch lines. I did mimes to pre- recordings, and that was my act. He never saw the show. I knew when I read it that son of a bitch wasn’t there!” The year of the review? 1945.

The conflicted Kid

There is a bewildering and entertaining contradiction at the heart of Jerry Lewis: He is at once selfless and self-obsessed, a mensch and an egomaniac, poignant one moment and bathetic the next. You can see this in his movies, in his house, in his very person. It comes out in single facial expressions, as when he stares at you meaningfully only to lift his cheeks, stick his tongue out and squeal. He is still, at 78, The Kid.

These contradictions do not escape Lewis. The Kid has always been lucid and startlingly candid. His entire film oeuvre can be seen as an effort to explore his conflicted self.

Looking back, it seems clear that it was Lewis and not Woody Allen who first used the movie theater as a substitute for the psychiatrist’s couch. This may help explain the polarized reactions that his work inspires. People who have never met the man either love Lewis or hate him, because they feel that they know him.

Though the Martin and Lewis movies were by all accounts only a shadow of their live act, Lewis’ restless, almost uncontrollable mind still translated indelibly onto the screen. He filtered the great physical comedians of the silent cinema into the sound era (going so far as to travel repeatedly to Switzerland to confer with the exiled king, Chaplin).

So much of their act found root in Lewis’ own insecurities, and those too found their way to a mass audience. In film after film and show after show, he and Martin reprised the relationship that they’d invented early on -- “the playboy and the monkey,” as Lewis called it. In “The Stooge,” “Pardners” and “Hollywood or Bust,” for instance, Martin’s characters sashayed about, breaking hearts and crooning, while Lewis’ sensitive, bumbling man-children followed along, entranced. Such was the team’s public persona, and it worked so well in part because everyone believed it was their private one as well.

After their well-publicized and emotional (for Lewis at least) breakup, Lewis carried the monkey into a slew of hits in the ‘60s, at first just as the star and then, almost overnight, as an auteur. Varyingly widely in quality, Lewis’ output from that decade was consistent in that it always offered to the audience -- one might even say forced on them -- Lewis’ unscrubbed id. In films such as “The Patsy,” “The Errand Boy,” and, most famously, “The Nutty Professor,” his deepest cravings for acceptance and his worst immodesties are on full display. He was a half-reluctant, half- gloating star making movies about half-reluctant, half-gloating stars.

After years of this kind of thing, it’s no wonder audiences grew weary, and by the 1970s, after a string of failures, Jerry Lewis had become something of a liability in Hollywood. The Kid still thought he had it, but no one else did. His public downfall has since been encapsulated neatly in the debacle of “The Day the Clown Cried,” in which Lewis plays a German clown who entertains Jewish children in Nazi concentration camps. Made in 1972, the film, which he also directed, has never seen the light of day and Lewis refuses to talk about it. He did not pick up a camera again for eight years.

In 1983, Lewis gave a startling performance as the vain, human talk show host Jerry Langford in Martin Scorsese’s “The King of Comedy,” and a new generation of critics realized, with a start, that The Kid could really act. But by that point, Lewis was thoroughly disenchanted with Hollywood and did not attempt to parlay his resuscitation into a full-blown comeback. In the 1990s, he delivered two more unexpected and astounding performances in the little-seen but masterful “Funny Bones” (as a vain one-time star) and the cult-favorite “Arizona Dream.”

Lewis is acutely aware of his public image, of the apexes and nadirs of his 60-year career, of the access he’s allowed and its accompanying pitfalls. He is, after all, an intellectual who lives in Las Vegas.

“I wouldn’t talk to someone about a particular issue, but I would shoot it,” he said.

Did he ever get over that?

“No. There’s no separation.”

It is these same contradictions that make the telethon, for all its sappiness, such hypnotic watching. Seen one way, it is a piece of streamlined showbiz puffery. Seen another, it is a raw psychological performance piece for Lewis, a cracked mirror he holds to his face once a year. (One gets the feeling that the telethon and not any movie is what persuaded Scorsese to cast Lewis as Langford in “King of Comedy.”) And then of course there is the fact that he’s raised nearly $2 billion for sick children.

At 6 p.m. promptly Sunday, the night before Labor Day, the proceedings began with an antic video sequence. Lewis, in a yellow raincoat, was whisked in an antique fire engine onto the CBS lot. He burst onto the stage to a frenzy of applause.

But barely had the clapping faded than Lewis turned serious and announced that the telethon was dedicated to the memory of Mattie Stepanek, the 12-year-old poet and MDA goodwill ambassador who had died in June. A memorial, complete with bagpipes, was performed. Thus, only minutes after it was laughing, the audience was in tears.

The next 21 1/2 hours wrenched the crowd through this same back- and-forth. Everything hued to a down-to-the-minute script. Comedy acts precede tearful pleas, dance routines follow fast upon video biographies of children in wheelchairs. The atmosphere was almost bipolar -- laughing, crying, laughing, crying -- and an air of timelessness, however cheap and glittery, however reeking of Brylcreem and too much cologne, hung over the stage. This was a not very good vaudeville variety show, nothing more and nothing less, and aside from Celine Dion’s satellite feed from Las Vegas, it could have been 1958.

Through it all, Lewis sat at his podium, a glass of Diet Sunkist at his elbow, not so much presiding over the ceremonies as taking them in. He looked engrossed at certain moments and hopelessly bored at others. He regaled McMahon with every new monetary milestone, digit by digit: “41 million, 2-6-2, 5-1-6!” He noodled Tony Orlando, his co-host in New York -- “You’re the first Puerto Rican who ever spoke to me in person!” -- and blew kisses to the crowd.

He laughed like a child when his obese comic friend Max Alexander from Vegas recounted losing $400 to a candy machine and wept inconsolably when crooner Jack Jones hit the chorus of “Joey’s Song.” (It was dedicated to Joe Stabile, Lewis’ late one-time manager.) A stream of suits and uniformed firemen walked to the podium diffidently and handed him whopping checks.

Many years before, the telethon had been an A-list affair. Frank Sinatra, Carol Burnett, Stevie Wonder, Jimmy Durante, Johnny Cash, Sonny and Cher were once regulars. The star power had decreased significantly by the 39th year. There were schlocky Vegas magicians and aging comics with hearing aides. Larry King, who filled in for Lewis during the wee hours, was by far the most famous person on hand. Lewis’ style had toned down as well. He no longer stalked the stage, smoking, swallowing the mike, as he used to do. He no longer had that crazed, sweaty-browed stare. He just persisted. Still, by Monday afternoon, the 22nd hour approaching, Lewiswas clearly exhausted. His bow tie hung undone, his jacket open. After a few closing remarks, he sang “You’ll Never Walk Alone,” leaving the house whimpering and reaching for tissues. And then without another word, he was off in his cart, back to the hotel. McMahon was left to greet the well-wishers.

Lewis did not reach the “dollar more” he strives for every year. 2003’s total was $60.5 million; this telethon raised $59.4 million.

His regal imprimatur

A month later I am in Las Vegas to talk to Lewis some more.

Lewis does not live in one of the wealthy new Vegas suburbs or on a golf course, as one might expect, but rather on a deserted lane in the middle of the city, a few minutes’ drive from the Strip. At the end of the lane is a highway, blocked from view by a large wall. Nearby is a strip mall. The unlikely neighborhood, called the Scotch Eighties, was built before the urban blight of Vegas could have been imagined.

He leads me into his study, whose walls are lined with photographs of Lewis, with and without celebrities and statesmen -- Cary Grant, Sinatra, Marilyn Monroe, Charlie Chaplin, JFK. Neat stacks of videos, DVDs and CDs -- comedy compilations, TV anthologies, box sets of all sorts -- line the floor. That laughing caricature in profile is affixed to any number of things, and a role of stickers printed with it sits on the desk. An NBC stagehand drew it in the late ‘40s, and it has become his regal imprimatur. It’s on the MDA website, on his tricked-out golf cart, all over his office. “If you went somewhere in this country or for that matter in Europe and you saw that logo would you know who it was?” Lewis asks, seeming to earnestly want an answer. “I mean, it’s embedded,” he says.

Does he go to France much anymore?

“Sure, when I need a fix,” he says.

Before the telethon, I’d asked Lewis why he’d curtailed his work 20 years ago. He’d burnt out, he’d said, and wanted to relax for the first time in his life. “The entertainment industry leaves a lot to be desired,” he’d added.

I ask him again.

“The state of the entertainment industry today is the buck,” he says. “The creative aspect of it has been pushed aside. How creative do you have to be to hire some guy from Toronto, Canada, who presses buttons and connects that cut to that cut? Where’s the movie-maker? He’s an electrician. The guy that puts the bulb in your toilet and cuts your movie.” As his assistant brings in two Diet Sunkists -- “In the can!” Lewis insists -- he plops a stack of his newly released DVDs on the desk.

He relishes the idea that a new generation of viewers will see his work, and he’s been putting in long hours on the project. And yet when Lewis is asked how it feels to go through his life’s work again, he responds simply, “Oh, it was great fun.” Nothing more.

Spurred on by the previous night’s presidential debate, the conversation, such as it exists, moves to politics. Lewis launches into a tirade about bombing Pakistan. If there had been any doubts, it becomes abundantly clear that he is not in a good mood. He’s had a cold for several weeks and is coughing a lot. He trembles slightly. He seems preoccupied, even annoyed at times.

Talking about the presidents he’s known and performed for lifts him for a time. Franklin Roosevelt was the first. Lewis did his act for him in 1945, he says. He was close with Ronald and Nancy Reagan, knew the Nixons and Fords. But the one commander in chief he adored, he says, was Kennedy, whom he met in Chicago when Martin and Lewis were playing the Chez Paris and Kennedy was making his first run for Senate.

“We became very fast friends,” he says. “I never entered the White House like regular people. I was flown on Marine One from Dulles to the Rose Garden and led down into the bowels of the White House, to come into the Oval Office. And that way the press never knew I was there. It was great. It was great.” Lewis begins visibly tearing up.

And then, after a brief rant that progresses from child poverty to prescription drugs to the cost of movie tickets, an odd thing happens. Lewis shuts off. At one point, he begins feeding his dogs miniature Milk-Bones, and the conversation dies entirely.

Surely, his health has much to do with his mood. But it is clear something else is at work too. Lewis’ sudden mood swing has a child’s petulance about it. Endearing and discursive for a time, he is now suddenly, adamantly sullen. Lewis is invigorated by people and pressure; the dark side of that trait is that anything less is like sensory deprivation, and it seems to drain him. Perhaps it is a performative liability. Realizing he’s captured his audience, he loses interest, seems resentful even. It is another easy conquest. He’s had too many of them.

As I walk out of this little shaded cloister in the middle of Las Vegas, I recall something Ed Simmons, a longtime writer for Lewis, said about him in a biography: “Jerry once was very funny. It isn’t that Jerry changed. It’s that he should have changed but didn’t. Because he at 66 or 67 years old is still The Kid. And he was The Kid through all those movies even when he wasn’t The Kid. And he did not grow.... Everybody who does an impersonation of Jerry Lewis does Jerry from the ‘50s.” And then, something that Lewis once said, or says he said, occurs to me. It is written on a plaque given to him by JFK that hangs in his study: “There are three things that are real ... God, human folly and laughter. Since the first two are beyond our comprehension, we must do the best we can with the third.”

*****************

A Jerry Lewis filmography

Paramount recently released several of Lewis’ film comedies on DVD, a collection of farces that represent the great moments, the good work and the misfires of his career.

“The Stooge” (1953)

Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis were at the peak of their popularity when they starred in this comedy with dramatic elements about a revue performer on the skids who becomes a success when he hires a stooge to heckle him from the audience. The film was shot in 1951 but delayed for two years because Paramount was unsure about how fans would accept the dramatic moments.

“The Delicate Delinquent” (1957)

Lewis’ first film without Martin was originally envisioned as a vehicle for the duo. But when they broke up, Darren McGavin took over the Martin role as an understanding cop who mistakes a bumbling janitor (Lewis) for a member of a gang and persuades him to join the force.

“Cinderfella” (1960)

One of Lewis’ most popular films thanks to the inventive direction of Frank Tashlin, the former Warner Bros. cartoon director. Lewis is perfectly cast in this gender-bending version of the “Cinderella” story.

“The Bellboy” (1960)

Lewis made his directorial debut with this absurdist comedy in which he plays a mild-mannered bellboy at the Fontainebleau Hotel in Miami Beach as well as himself. Lewis, with Milton Berle, above, shot the film in four weeks while performing at the Fontainebleau.

“The Ladies Man” (1961)

Lewis plays a college grad who, after his girlfriend leaves him, gets a job working in a massive Hollywood boarding house inhabited by beautiful women. The comedy is all over the map, but the huge boarding-house set is an eye-popping wonder -- built on a Paramount soundstage, it was four stories high with a working elevator.

“The Nutty Professor” (1963)

This is widely regarded as Lewis’ best film. A surreal, funny spoof of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, it has Lewis playing a nebbish college science teacher in love with Stella Stevens’ character who creates a formula that turns him into a slick womanizer named Buddy Love. The Library of Congress last week added the movie to the National Film Registry.

“The Patsy” (1964)

After a famous musical comedy star is killed in a plane crash, his team has to come up with a replacement. And they discover the next big thing in the form of a nerdy hotel employee.

“The Disorderly Orderly” (1964)

Lewis directed his own films after “Bellboy,” but here turned over the reins to Tashlin in what would be their last collaboration. Lewisplays yet another in his long line of bumblers -- a hospital employee who can’t do anything right.

“The Family Jewels” (1965)

Lewis plays seven roles in this strained comedy about a young heiress who must choose a guardian from six crooked uncles. The film introduced the song “This Diamond Ring,” which was sung by Lewis’ son Gary and his group, the Playboys.

-- Susan King.

See the most-read stories in Entertainment this hour >> »

ALSO:

Jerry Lewis, legendary comedian, has died at 91

From the Archives: Here’s what happens when Jerry Lewis isn’t so hostile in an interview

From the Archives: Jerry Lewis walks alone: The ritual of the Muscular Dystrophy Labor Day Telethon

Hey laaaaady! Jerry Lewis’ personal archive is acquired by the Library of Congress

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.