In ‘Echo in the Canyon,’ Jakob Dylan chases the origins of the California Sound

Beneath a canopy of live oaks, the cars were in a bottleneck, all trying to weave past one another on a narrow hillside road.

“This isn’t a very hippie vibe,” Jakob Dylan said, as the truck in front of him laid on its horn, drowning out the birdsong above.

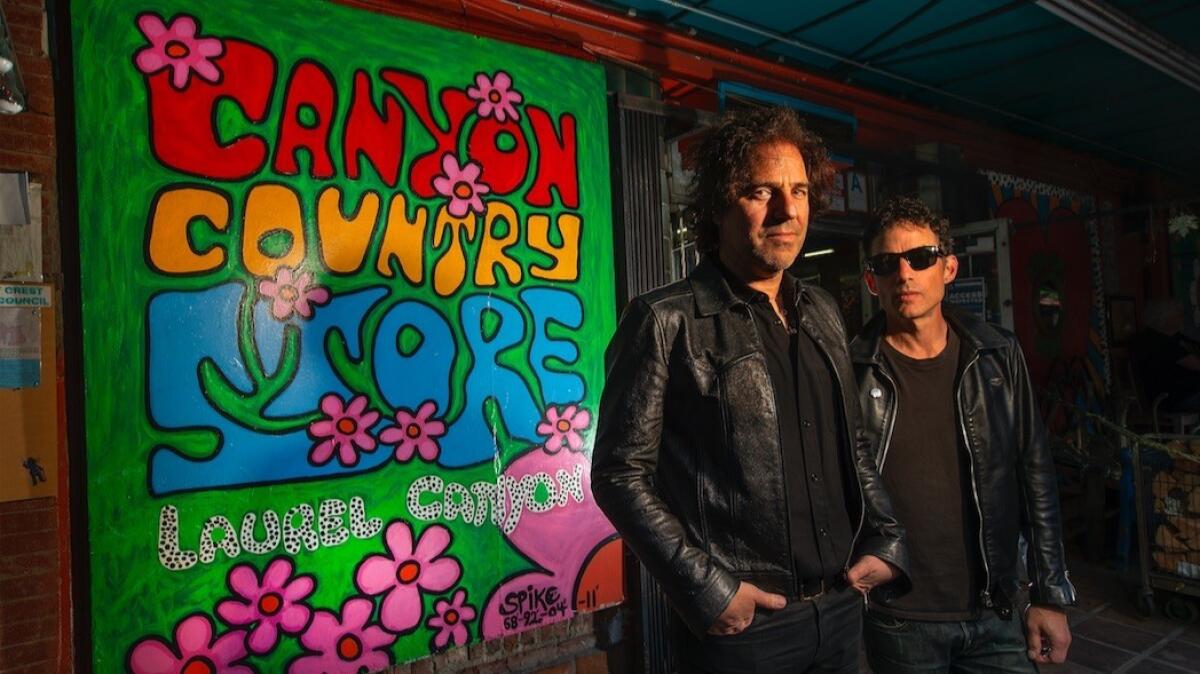

The Wallflowers frontman was sitting in the passenger seat of a silver 1967 Pontiac Firebird next to his longtime friend and manager, Andrew Slater. Slater had been driving his convertible up and down Laurel Canyon for the better part of an hour, stopping in front of historic homes once owned by the likes of Stephen Stills and Micky Dolenz in the ‘60s.

“You know, there’s not much to look at here, anyway,” Slater said, as the car lurched toward the English country cabin where Mama Cass Elliot, the late Mamas and the Papas member, had lived. “To us, the idea of Laurel Canyon isn’t so much the specific homes as it is the idea of community and the cabal that existed at the beginning.”

Few know the history of the iconic neighborhood better than Dylan and Slater, who have spent the better part of the last decade working on a documentary about the place that gave birth to the California Sound. “Echo in the Canyon,” which debuted in Los Angeles this weekend, explores how the first bands that came to the area in the mid-’60s — the Byrds, the Beach Boys, Buffalo Springfield and the Mamas and the Papas — took the influence of the Beatles and evolved it.

Slater, a former chief executive of Capitol Records, always idealized the West Coast as a boy growing up in Queens, New York. As he listened to “California Dreamin’” and watched “It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World” at the theater, a fantasy started to form in his mind — that of a place where there was space and warmth and freedom.

Dylan, of course, had a different vantage point on Hollywood. As the son of Bob Dylan, Jakob was raised in Malibu and got his first place in Laurel Canyon at 19. He moved there because he wanted to be surrounded by mountains and trees — not because he was trying to harness any magical music vibes that might be floating around. But he wrote the biggest album of his career at his kitchen table in that home off Mulholland: 1996’s “Bringing Down the Horse.”

“So maybe there is some voodoo in Laurel Canyon,” Slater suggested.

Review: Jakob Dylan and ‘Echo in the Canyon’ recall the mid-1960s Harmonic Invasion »

The two crossed paths around that time, when the younger Dylan’s career was just taking off. They’d cruise around together in the Firebird, trying to figure out what the singer wanted to record. Often, they’d stop in at bars Dylan was technically too young to gain admittance to. (He’d get in with Slater’s help.)

But it wouldn’t be long before the music manager’s penchant for partying got the best of him. In 1991, shortly after he’d been fired by Don Henley and Lenny Kravitz, he checked into rehab. According to a profile about the music executive published in The Times in 2000, the only client who visited him during his monthlong stint at the facility was Dylan.

Rehab was pivotal for Slater. He would go on to help launch the careers of Fiona Apple, Macy Gray and, of course, the Wallflowers. His track record garnered the attention of Capitol Records, where he served as president for seven years. He was ousted in 2007 when EMI Group merged its Capitol and Virgin labels.

Not long after, he and Dylan were hanging out one night, flipping through the channels on television. They stumbled across a movie on TCM called “Model Shop,” a 1969 Jacques Demy film about a young man finding himself in Los Angeles. As the film’s protagonist wandered around ‘60s Hollywood landmarks, the friends were reminded of the time period that had attracted them to the music industry in the first place, and they started contemplating recording some classic songs from the era.

“Maybe in a sense, we were rejecting the contemporary music business — or the contemporary music business was rejecting us,” Slater said, now steering his car out of the canyon and toward some old recording studios on Sunset Boulevard. “We were like, ‘Let’s go back to what we really love about where we live, and the reason we got into music in the first place.’”

But as they began revisiting their favorite songs — ultimately organizing a tribute concert at the Orpheum in 2015 — they began to consider making a film, too. They weren’t interested in Laurel Canyon’s ‘70s heyday, when Joni Mitchell and Carole King ruled. Instead, they wanted to go back even further, to what Slater calls the “initial age of innocence,” when Roger McGuinn saw the Beatles in “A Hard Day’s Night” and picked up an electric 12-string guitar.

“The dream really started with ‘A Hard Day’s Night,’ because you saw these guys having so much fun, they were on a train, living together, playing together — they were their own little gang. And that’s why everyone wanted to do it,” said Slater.

“Even if it wasn’t true, it looked true. I don’t think bands act or behave like that anymore,” added Dylan. “Communal like that, where you could have three writers in a group who weren’t really thinking about themselves or their own careers yet. By the time I came along years later, I don’t think anything looked or felt the same. It sure seemed awfully simple [compared] to the muck we deal with now, you know?”

Initially, Slater did not intend to direct the film. While he’d worked on music videos before, he didn’t feel he knew enough about the craft to tackle the job. But after being turned down by a handful of filmmakers, he and Dylan decided to make the documentary themselves, with the musician serving as the executive producer and conducting interviews with key subjects like Ringo Starr, David Crosby, Jackson Browne, and — in his last film interview — Tom Petty.

“When you have Jakob, it’s not that hard to get these folks,” said Slater. “The first person who we sat down with was Eric Clapton, who Jakob had worked with — so that was kind of an easy one.”

“That’s easy for you to say,” Dylan said with obvious sarcasm in his voice. “It’s still not easy to ask. And in my phone — because I’m respectful of people — his initials are the same as Elvis Costello, so I do get confused sometimes with which one I’m trying to talk to. I know — I sound awful when I say that.”

Because he is a fellow musician, Dylan said, his subjects may have “felt more free” opening up to him on camera than they might with a journalist.

“You’re asking a lot of people to look back 50 years and tell you what it was like,” he said. “How many requests do you think Stephen Stills has to talk about those days? I can imagine being one of them saying, ‘Please, no more of that.’ But they didn’t act like that with us.”

And if you’re wondering if Dylan’s father turns up in the film, the answer is no. He wasn’t asked to appear in the movie, nor has he seen it yet.

“I’m not sure if you’re aware, but he does not do a lot of interviews, let alone on camera,” said Dylan, who still feels uncomfortable talking too much about his dad. He said he’s normally asked about his father at the end of an interview, and that ends up being the headline of the story, so he tries to avoid “the curiosity factor — my background growing up, which is usually less about me than it is about somebody else.”

Slater pulled the Firebird into the driveway of East West Studios — formerly known as Western Recorders — and parked. Inside, he and Dylan headed toward Studio 3, where the Beach Boys famously recorded “Pet Sounds.” On this day, the room was being rented by a rap artist and reeked of marijuana. But the “Pet Sounds” vinyl still rested on the glass above the sound board, a reminder of what once had been.

“You do feel something when you’re in these rooms,” said Dylan, who shot an interview for “Echo in the Canyon” in the studio with producer Lou Adler. “I don’t feel ghosts or anything. But it feels like you’re going to get something done. I do right now. I wish I was recording something.”

Dylan, whose last album was released in 2012, said he was eager to get back to his “normal job” after the movie is released. Making the film, he said, reconfirmed something he’d forgotten — how important it is to plot out the melody and core structure of a song before recording it.

“Going in and just jamming to express doesn’t work for me,” he said. “None of these people were allowed to get in the studio until they had proper songs. I haven’t heard the word ‘preproduction’ in like 20 years. You can just undo things with the touch of a button. So I think this break has been really good and inspiring. A lot of people are nervous to step off the treadmill, but it’s been a nice diversion from the same ol’, same ol’. You can’t be inspired every year — nobody can.”

Slater, meanwhile, is keen to continue directing. He’s not leaving music — he still works with Apple and Cat Power — but found putting a movie together similar to working on a record and trying to figure out how to get the most out of each musician.

He said he hopes the film “transports people outside of the vicissitudes of daily life and the age we’re living in. We derive so much joy from bad guys getting taken down now, but the period in the film is one of kindness.”

“And,” Dylan added, “if there’s a 15-year-old kid who might not have heard the Byrds otherwise, and they do now — that’s important. Those artists are the building blocks of so much of rock ’n’ roll.”

Follow me on Twitter @AmyKinLA

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.