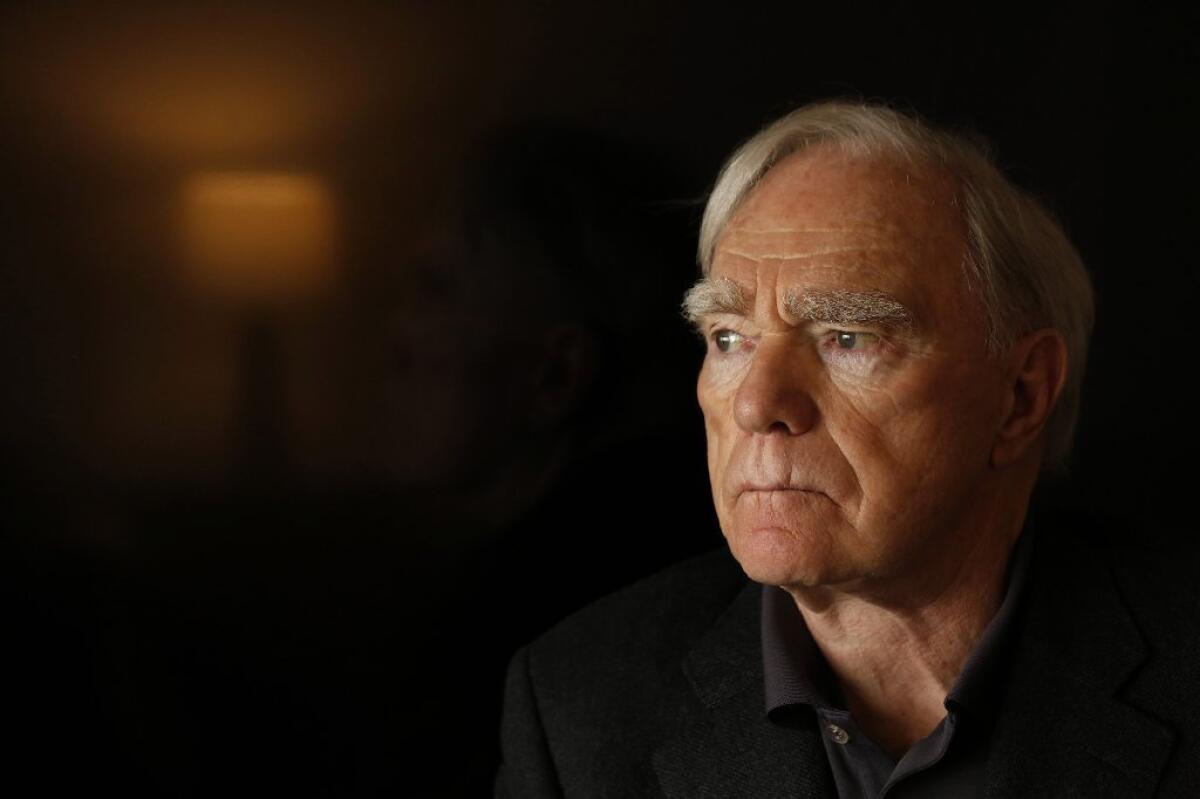

Screenwriting guru Robert McKee writes his story’s next chapter

In the early 1990s, Robert McKee had a revelation that would change the course of his career and influence the lives of tens of thousands of other writers. At the time, he’d written “Abraham,” a four-hour biblical miniseries, for TNT and had sold several unproduced screenplays.

“I looked at ‘Abraham’ and thought, ‘I’m a good writer but I will never be Ingmar Bergman,’” McKee said. “The creative explosion is not happening. It’s professional, it’s actable, it’s entertaining. But I want to be the best at whatever I do.”

McKee turned his focus from writing for the screen to teaching screenwriting, leading a popular, multi-day seminar and publishing a bestselling book, “Story,” in 1997 that became a bible to many aspiring scribes. Nearly 20 years after “Story,” McKee has finally written his follow-up, “Dialogue,” published this month by Twelve Books.

Over 296 pages, drawing on narratives from “Richard III” to “30 Rock,” McKee tackles the widely held belief that dialogue is unteachable, that a writer either has an ear for it … or doesn’t.

“People think dialogue is unexplainable,” McKee said. “Great dialogue has transparency. Something is being said while something else is being felt…. You sense not only the unsaid, but the unsayable. When dialogue achieves that kind of multilayered expressivity, it becomes really terrific stuff.”

McKee lives in western Connecticut with his wife, Mia, and teaches around the world, leading semiannual courses in L.A., New York and London.

The cinema as an art form is shriveling ... the quality writers have all migrated to TV.

— Robert McKee

In April, at one such seminar in a windowless conference room at the LAX Sheraton, the 75-year-old McKee was pacing the stage and dispensing a tough-love sermon about the screenwriter’s life.

“Becoming a writer … it’s going to cost you time,” McKee said, looking out over the room of about 150 students, a diverse mix of ages and races. “It’s going to cost you money. It’s going to cost you people.”

With his white hair and sport coat, and a theatrical scowl reserved for movies he hates, McKee brings a ruthlessly honest, “Paper Chase”-style of pedagogy to the hopeful world of would-be writers. He believes that film schools, by emphasizing expression over technique, are failing writers.

“The teaching of writing at film schools is so undisciplined,” McKee said. “Oh, pour your heart out, write anything you want. It’s the Vesuvius school of teaching. You’re just a volcano of creativity, just let the magma pour out. … They come out more in a fog than when they went in. People come out of the universities dissatisfied.”

Born in a Detroit suburb, McKee was a Fulbright scholar who earned a bachelor’s degree in English literature and a masters in theater, both from the University of Michigan. He studied Shakespeare at the Old Vic in London and spent years as an actor and director on Broadway in the 1970s before moving to Hollywood. He worked as a story analyst for United Artists and NBC, wrote episodes of TV shows such as “Spenser: For Hire” and “Kojak” and began teaching a popular course at the USC School of Cinematic Arts.

“Teaching [writing] was more fascinating to me than doing it,” McKee said. “Writing about it engaged my intelligence in a way that fiction writing did not. The questions were much larger. In fiction writing, the question is, ‘What happens next?’ But in writing about writing the question is, ‘What is this?’ That, to me, was a bigger, more important, more engaging question than what happens next. That task grabbed ahold of me like a leech and wouldn’t let go.”

Among the tens of thousands of people who have taken McKee’s course over the years are Andrew Stanton, Peter Jackson, Ed Burns, Jane Campion, Akiva Goldsman and Meg Ryan. Companies and organizations including NASA, Microsoft, Disney and PBS have brought him in to speak to employees on the subject of story.

The case can be made — and critics including “Basic Instinct” writer Joe Eszterhas have — that McKee has been too influential, particularly among creative executives, resulting in a boring homogeneity of approach to story in Hollywood.

With all the writers he has affected, it was perhaps inevitable that McKee eventually became a film character himself, played by Brian Cox in the 2002 metacomedy “Adaptation,” directed by Spike Jonze and written by Charlie Kaufman. In the film, a screenwriter played by Nicolas Cage grapples with a case of writer’s block and attends a McKee seminar to ask for advice.

Though the character is something of a spoof on McKee’s quasi-scientific approach to a creative art form, McKee clearly sees it as an affectionate one — in the scene, spiral-bound copies of the “Adaptation” shooting script are for sale outside the conference room at the Sheraton for $20, alongside scripts for “Chinatown” and “Casablanca,” copies of the screenwriting software Final Draft and T-shirts with McKee’s face on them that say, “Write the Truth.”

One of McKee’s pet peeves is the auteur theory, the more than half-century old idea in film criticism that it is the director, not the writer, whose creative vision appears on the screen. McKee looks to the contemporary flowering of storytelling on television, where writers are in charge, instead of film, as evidence that auteurism is absurd.

“The cinema as an art form is shriveling,” McKee said. “It’s true that the director’s interpretation is the difference between a good film and a great film. But the difference between a good film and a bad film is the writer. The quality writers have all migrated to TV.”

The next great techno-cultural change affecting McKee’s students, however, is learning to write the kind of stories the audience can watch on their phones. “You have to hook ’em, hold ’em and pay ’em off in three minutes,” McKee said. “Good luck!”

For his own entertainment, McKee lately prefers television, particularly for the complexity of characters in long-form series like “The Sopranos,” “Breaking Bad” and “Game of Thrones.”

“Tony Soprano is a 12-dimensional character, Walter White is 16-dimensional,” McKee said. “The notion of a three-dimensional character as standard? No. That’s a supporting character at best.”

After “Dialogue,” McKee is planning a third book, “Character,” and then he’ll turn to specific genres.

“If I live long enough I’m hoping to have a shelf of eight to 10 books,” he said.

There is certainly plenty to write about. Because of the modern phenomenon of peak TV, McKee believes we are in the midst of some of the most demanding, complex storytelling in history.

“We’re watching human creativity at a density and scale we’ve not seen before,” McKee said. “We accept it because it’s TV. In a way it’s what Shakespeare’s audience experienced. They went to Shakespeare for a good time and they sat there and cheered and cried and laughed and carried on. It was only four centuries later that it became an exercise in academic understanding.”

Twitter: @ThatRebecca

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.