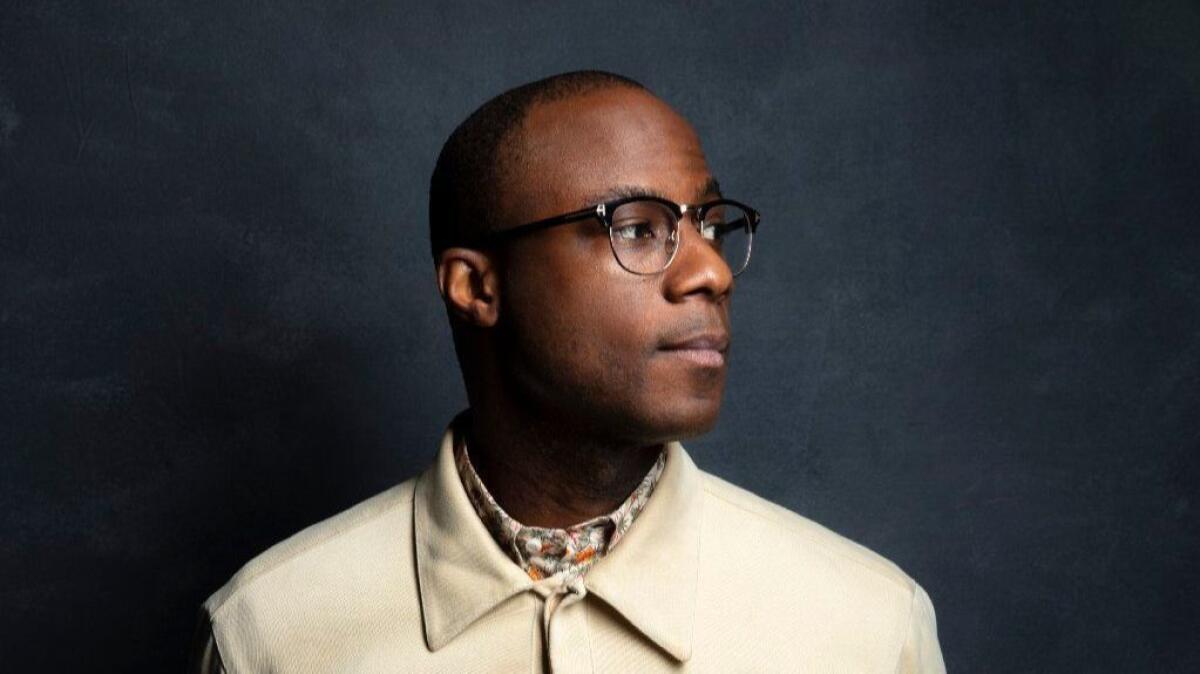

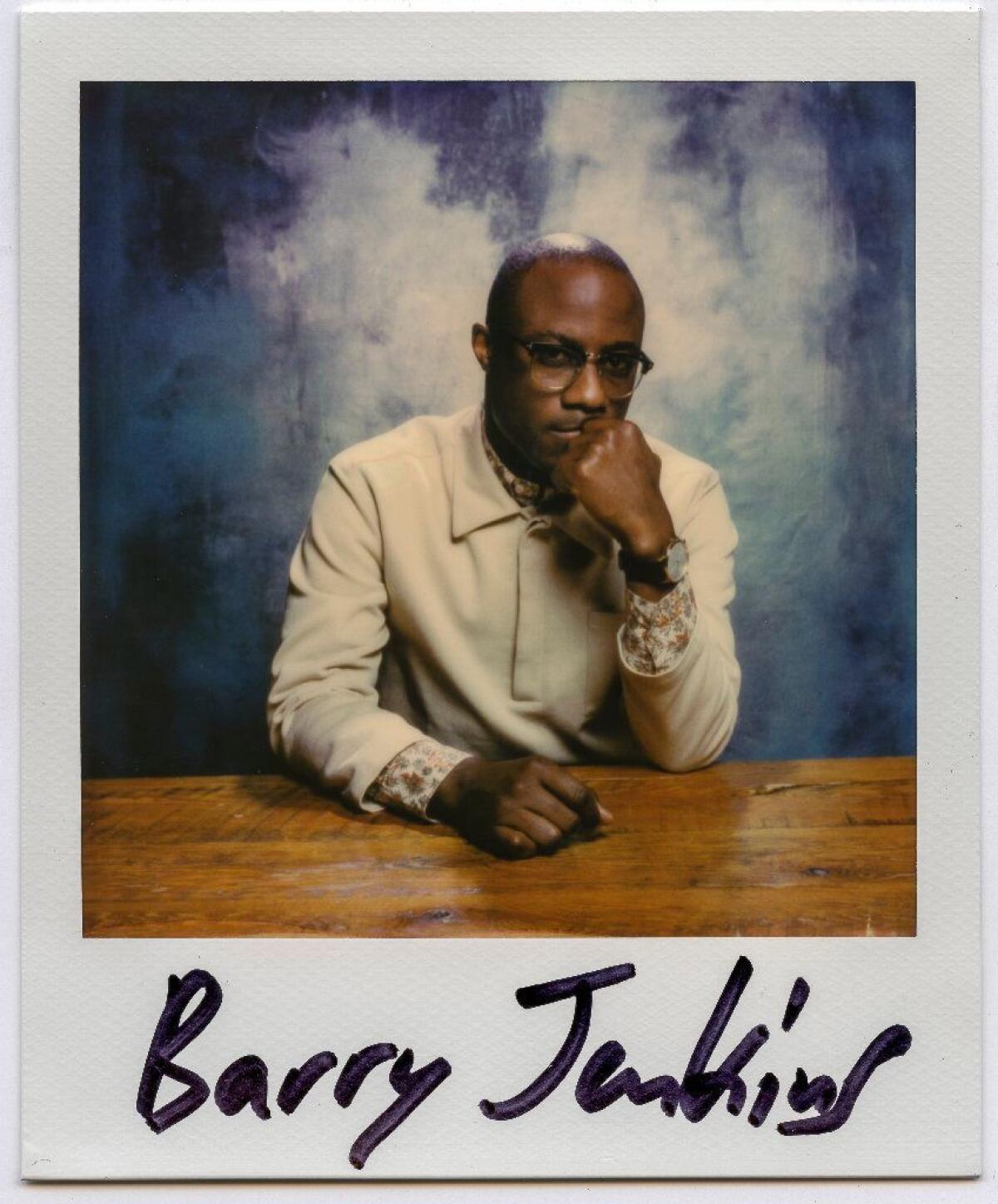

‘If Beale Street Could Talk’: Barry Jenkins on staying faithful to James Baldwin and #MeToo

Reporting from Toronto — James Baldwin means different things to different people.

To some, Baldwin is the prototype of the artist as activist, his writing an example of how to battle injustice and prejudice against black people in America. To others, he’s one of the foremost purveyors of the black experience, his mastery of language precisely capturing what life was, and is, like for African Americans in an oppressive society.

Those two aspects are forcefully represented in Baldwin’s 1974 novel “If Beale Street Could Talk,” noted Barry Jenkins, the Oscar-winning filmmaker of “Moonlight,” and a reason why he wanted to adapt the book for the screen.

“Mr. Baldwin has many different modes,” Jenkins said. “One of those modes is the protest, the anger. And then there’s the lush, the romantic, the hopeful. I think with ‘If Beale Street Could Talk,’ you find the best pairing and balancing of those two things. It was a challenge worth undertaking.”

I did think that it was going to be something really potent about seeing two dark-skinned black people loving each other the way they do in this film.

— Barry Jenkins

FULL COVERAGE: 2018 Toronto International Film Festival »

“Beale Street” is a love story centered on a young Harlem couple, Tish and Fonny, played, respectively, by newcomer KiKi Layne and Stephan James (“Selma,” “Race”). When Fonny is arrested after being falsely accused of rape, a newly pregnant Tish, along with her family, scrambles to prove his innocence.

Regina King, Colman Domingo, Teyonah Parris, Aunjanue Ellis and Brian Tyree Henry also star in the picture that will hit U.S. theaters Nov. 30.

The Times sat down with Jenkins after the film’s world premiere at the Toronto International Film Festival to discuss “Beale Street’s” early reception, how he secured the rights to the Baldwin book before his “Moonlight” breakout and how a number of pivotal scenes might be received by audiences in the #MeToo era.

Why “Beale Street,” of all of Baldwin’s work?

A friend who I really trusted gave me the book and said, “Have you read this?” I was shocked that I hadn’t. And she said, as a person I trust, “You should read it, and I think you should make a movie of it.” Now, people say that all the time — even back then [before “Moonlight”], when I didn’t have any real access. But I read it and I thought she was right. There was something about the love between Tish and Fonny that just grabbed me, and how that rhymes with the love between Sharon [played by King] and Joseph [played by Domingo] and, of course, all this [stuff] that Tish and Fonny have to go through. It just seemed really rich. And I thought, “If I was going to tackle Baldwin, this is the one thing I could do now with my skills.”

Baldwin’s estate is notorious for saying “no” to everyone who wants to adapt James Baldwin. But you got them to say “yes.”

Actually, Jake Gyllenhaal is kind of one of the reasons this happened. He’s a big Baldwin fan, and he had been talking to the estate, went through the channels and got them to respond to his queries about another project. And then I just happened to write them a letter, literally, the next day. And a woman at the estate — not Baldwin’s sister Gloria Karefa-Smart, who runs it — but the woman who runs all the official documentation, she said, “Well, I felt kinda bad because we were listening to Jake Gyllenhaal and we don’t ever want to be the kind of estate that only listens to famous people” — I was nobody at the time — “so when your package came through, we were like, ‘We might as well listen to this guy named Barry Jenkins.’” And here we are.

Because you had written the “Moonlight” script and this script at the same time, so this was before all the craze and the Academy Awards.

Way, way back in the day. What I love about Mrs. Karefa-Smart is that she’s pretty adamant about saying it was “Medicine for Melancholy” for her. At that point, I hadn’t made “Moonlight” and had sent them samples of my work — the short films, the feature, other scripts that I had written and the script for “Beale Street.”

What do you think it was about you and the script that made them say “yes?”

Baldwin’s legacy is very rich and, I would say, important, justifiably so, and so, instead of coming to them and pitching about what I was going to do, I just handed them the script. It was really clear what I was planning to do and the adaptation was more or less faithful [to the book]. I can’t speak for Gloria, but she watched “Medicine for Melancholy” and saw something in it that translates well to Baldwin.

Talk to me about your decision to cast KiKi Layne and Stephan James as the leads. Some have already questioned James, saying he’s too attractive when compared to the character in the book.

I get where they’re coming from. The way Tish and Fonny are described in the book is different than how they look on-screen, especially Fonny. He’s light-skinned in the book — there’s this dynamic of colorism that we went away from because Stephan James was the best actor who came through the door. But when I’m writing characters, I don’t see the actor. I’m hoping an actor will walk in and reveal the character to me. Both KiKi and Stephan did that. They both taped, and in their tapes, I saw. It started to make sense to me, and I wasn’t concerned with whether Stephan was cute or not cute. He just seemed to be Fonny.

I really wanted Tish to be a dark-skinned woman. That was important to me. And trying to honor the text, I wanted Fonny to be a light-skinned man, because that’s how he’s written. But Stephan came in and his work was so strong and I thought, “If you’re going to flip this one way, it’s kind of OK to flip it this way, because we so rarely flip it this way.” It’s often the other way, where the character is written dark-skinned and we cast them lighter, often for the same reason where a light-skinned actor comes in and just crushes it. But it felt like the right thing to do.

I did think, once we made the decision, that it was going to be something really potent about seeing two dark-skinned black people loving each other the way they do in this film.

Were you setting out to have younger, newer folks that audiences aren’t as familiar with?

When you build a cast, all the pieces, all the components add up to a whole. I always like, if it’s possible, to give unknowns an opportunity, to give people who maybe haven’t yet broken through the opportunity to show me they can do this or that. It worked to great effect on “Moonlight,” and I feel on this one it functions the same way.

Baldwin has a particular grasp of language in how he captures the human experience, and, in particular, the black experience. Pre-premiere, you told me that the blackest scene of the movie involves the women of the film saying a lot of things that some might say are graphic or distasteful.

They are saying a lot of things, things that were written by James Baldwin. [laughs]

And you kept them in, despite how audiences might respond to them. Why?

I wasn’t interested in trying to translate the script from the ’70s to present day. I also wasn’t interested in curbing Baldwin’s words, the language. I felt like the things he was speaking to were authentic to the time, and authentic to today, to be honest. I’ve sat around with my family and seen some arguments pop off and heard things said very similar to what’s said in this book and film. I’ve never seen a scene like that. I’ve never directed a scene like that, and I felt like it was a great challenge for both myself and the actors to take the language, make it feel real and lived in, but also build a scene.

That scene is immediately preceded by an instance of domestic violence, but it plays in a comedic way to audiences. It felt real to me, but was confounding to some.

It’s almost like watching “Friday,” when [Chris Tucker as Smokey] says, “You just got knocked the ... out!” [laughs] And look, Baldwin wrote this, and I think he knew what he was doing. I think he knew where the language was going, and honestly, when you’re on set, people aren’t laughing… But I think it’s totally OK and totally fine for the audience to go, “That’s ridiculous” and “That ... is hilarious” and “Oh, no, she didn’t!” There is nothing wrong with that, and I’m actually quite proud that that sequence plays the way it does and then we come right back…

It’s funny because my cinematographer [James Laxton] was watching it at one point and he said, “This movie gives me a feeling and I’ve not been able to articulate until just now.” He goes, “As a white man, I don’t know what it’s like to be going about my day and it’s going beautifully and then one thing happens and now my day has completely turned. And then the next moment, the day turns again.” He goes, “Watching this film, I can’t help but have that feeling. It’s a whole new thing for me, and I don’t know how to process that.”

I think the waves of drama and comedy and then some of the more heavy procedural and social justice stuff, the way it keeps coming in these wavelengths reflects what it’s like to be black in America, at least in my experience. For example, you’re sitting at the after party for this program put on by the Academy [of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences] and somebody calls you a “nigger.”

You shared that story — how your driver referred to you that way at the height of your visibility for “Moonlight” — for the first time onstage after the premiere. What compelled you to share that story?

I had never shared it, but when the question came from the audience about a moment on set where I felt like what we were doing was on the right path, it was that scene with Brian [Tyree Henry] and Stephan and it wasn’t about the movie we were making in front of me but the things [making that scene] was triggering.

Somehow, I remember on set thinking back to that moment because — look, what happened at the Oscars is probably going to be with me forever. I’m always going to have some residual PTSD or whatever the hell you want to call it tied to that moment. Every now and again it comes back, and it did when we were filming and even us being on set, knowing that we were creating something, it triggered that memory. When the question came from the audience, I don’t know why, but it just came back to me. When I’m up there, I just start talking. [laughs]

You mentioned the scene with Brian Tyree Henry as Fonny’s friend Daniel Carty, which I find to be one of the least talked about so far, but perhaps the most beautiful. To see these two black men being intimate with each other, we still don’t see that a lot.

That scene could be 15 minutes if it wanted to be. Right now, it’s like 11 or 12 minutes. But we filmed it over the course of a day, and to me, it’s about how Daniel has already been through the experience that Fonny, theoretically, is going through over the process of the film. I think, sometimes, when two men meet — and I’ll go down further and say when two black men meet — you always have to present that you’re good. But most often, we’re not good. I love that over the course of this day, you see these two young men negotiate each other and slowly start to reveal themselves and let their guards down to the point where they are so comforted by each other’s compassion that they can reveal their full selves.

I felt that it was important to see those layers peel away organically… because, and I’ll speak to me in my personal life, it’s a difficult thing to do. But if someone gives you the space and the time and the care and compassion, you can get there. That stretch is about Brian Tyree Henry — such an amazing actor, bless his heart — going from on the sidewalk cracking jokes to essentially being paralyzed with fear over the course of 10 damn minutes. It’s one of my favorite stretches in the film.

And then there’s the rape story line. The rendering of it in the film, as it is in the book, is complex. Considering the film is coming out as we’re having all of these #MeToo-related conversations, did that give you any concern?

It did and it didn’t. We shot this film in October and November of last year, so it was right when all the Harvey Weinstein stuff was happening. But with everything in the adaptation, it was about a fidelity to the source material. I felt like Baldwin had done such a great job of also showing compassion for that character, Victoria Rogers. He could’ve very easily made her a Caucasian woman. Instead, he made her a Puerto Rican woman, I think, because how close can you get to the American dream but not have it be your dream, one you can obtain, than being Puerto Rican? — as we saw with the president going down there after the hurricane and shooting paper towels as a sign of help.

I just wanted to hew very closely to what was in the book as far as how we dealt with that. And what I really wanted to do was give Emily Rios, who plays Victoria, a chance to look the audience right in the eyes so the audience has to realize that there is someone here who has been victimized and she is not the antagonist in this film.

In a way, the system is the antagonist in this film, because whoever did assault this woman is still out there somewhere, and because this ... cop has it in for Fonny, we’re never going to know who that person actually is. I think it’s a film where everybody is allowed to present themselves and nobody is judged, not by the film or Mr. Baldwin at least.

Everyone seems to have, and have had, expectations based off of “Moonlight.” Was there any pressure or nervousness for you?

No. I wrote these at the same time, and so they’ve always been a pair to me, and the process of making them has been in motion for so long. I actually hoped to make this before “Moonlight.” They’re separate but the same, and I think this is not a reaction to “Moonlight.” It’s a reaction to that time when I was obsessed with both of these stories. I don’t know what people expected or are expecting. The movie is a thing unto itself and, I tried to make it in the voice it demanded to be made.

Is there a reason why you wanted to adhere so closely to the book?

Part of it was one, a respect for Mr. Baldwin and, two, this was the first adaptation in the English language of his work and only the second adaptation ever, the first one set in America, first one set in New York. I felt a responsibility to hew close to the text, and I felt like it would still give me enough freedom to do what I do while also being respectful of the work Mr. Baldwin did. I fell in love with the novel and felt like it was the right path to go down.

You’ve said before that you make movies for black people. Is there a different thing you think black audiences and other audiences will take away from “Beale Street.”

Yeah… yeah. [laughs] But, it’s not that we’re hiding things from nonblack folks in this film. It’s just Baldwin, and there’s certain things that are at the root, that are in the soil of the novel that are in the soil of people’s lives if they come from the background that we come from or from the background Mr. Baldwin came from. I’ve seen it and sat in screening rooms with audiences that [black] people are just connecting and clicking with something that is unspoken, a certain kind of energy, a certain kind of spirituality that doesn’t have to be spoken or articulated; it’s just felt. I think that’s the case with this film.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.