For Chinese artist Ai Weiwei, ‘free’ is a relative term

Reporting from BEIJING — His largest one-man show opened in Berlin in April, two more exhibits recently debuted in Britain, and his art currently occupies center stage at the Brooklyn Museum. Come September, he unveils an installation on Alcatraz.

But that’s not all Ai Weiwei has been up to. The Chinese political provocateur and cultural critic has, in the past two months, found himself in the midst of three media storms: two over efforts to censor his name and work from certain exhibits in China, and another over the use of his name and image.

It’s a blistering pace that would challenge even the freest and most fiery artist. What’s astonishing — as the new documentary “Ai Weiwei: The Fake Case” reminds us — is that three years ago, Ai was anything but free.

Accused of economic crimes by Chinese authorities, he was in solitary confinement, held for subversion of state power for blogging and “Internet activities.” After 81 days, he was released in June 2011, his spirit and his body wrung out. He was hit with a $2.5-million tax-evasion case and put under a yearlong probation, trailed and surveilled by security forces.

“When he came out, he was completely beaten [down]; he was not at all himself and was totally exhausted, physically and mentally,” says director Andreas Johnsen. “I had no idea if this was going to be a film about a guy who gave up, or if he was actually going to pick up the fight again.”

Johnsen’s film opens with a haggard Ai returning home the night he was freed and rebuffing a gaggle of reporters— “I cannot say anything,” he tells them. “I’m on bail.” So the fact that Johnsen was able to make his documentary at all may seem surprising, even given Ai’s renown as a master of mass media.

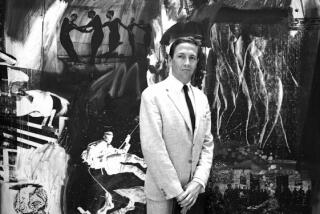

But as the bearded Ai explains in his Beijing studio last week, the Danish director had already been filming him for about a year, flying to Beijing for weeks at a time “to be part of my pretty ordinary but awkward life.” Ai had granted Johnsen access on the strength of his 2009 documentary “Murder,” about Nicaragua’s anti-abortion laws.

Johnsen’s shooting began in 2010, overlapping with that of Alison Klayman, who chronicled Ai’s life from 2008 to 2011. Her 2012 documentary, “Ai Weiwei: Never Sorry,” shadowed the artist as he moved from being a creative consultant on Bejing’s “Bird’s Nest” Olympic stadium to an increasingly incisive critic of the government, angered by issues like shoddy school construction that led to the deaths of more than 5,000 students in a Sichuan earthquake.

Johnsen’s film plays like a dark sequel to “Never Sorry,” showing Ai as he struggles with nightmares, insomnia and memory loss while plotting legal strategies with his attorneys and embarking on creating “S.A.C.R.E.D.,” a cathartic series of six claustrophobic dioramas inspired by his detention (now on display in Brooklyn).

His spirits are buoyed, though, by spending time with his son, Ai Lao, now almost 5, and visiting with friends and fellow artists.

An outpouring of donations to fund his tax case appeal also helps, though ultimately, he loses the suit. Some supporters folded banknotes into paper airplanes and lofted them over his studio walls.

Ai’s studio sits behind a high gray brick wall with a gate painted a tranquil shade of sea-foam green. A small sign out front says “258 FAKE”; Fake, a sort of multilingual pun, is the name of his studio. There’s a grassy yard inside and a patio with cats eating breakfast.

These days, Ai says, sitting at a massive wooden table at his studio, “The situation toward myself is much, much better because after the so-called one-year probation there’s much less direct contact with me.”

Still, authorities refuse to return his passport, making it impossible for him to go abroad for exhibitions. When he travels within China, agents are there, watching him at the airport or train station and following him to the hotel. Police surveillance cameras are perched across the street from his studio.

“Sometimes I get very angry because, you know, there is my family there,” he says. “So when I get angry, I would act a little bit ridiculous.”

The situation is affecting his son, Ai says. “He asked me, ‘Weiwei, did the police arrest you or did the Communists arrest you?’ I can’t even answer. I cannot say, this is the same thing! It’s too complicated.”

Among Ai’s associates seen in the film is attorney Pu Zhiqiang. Last month, Pu was detained by Chinese authorities after attending a commemoration of the 1989 Tiananmen Square crackdown in a private home; he remains in custody. Police then detained Pu’s own lawyer, his niece.

“The arrest of Pu Zhiqiang doesn’t really surprise me,” Ai says. “But arrest of his lawyer, his niece, that surprised me. Right after I talked to her, she got disappeared. That made me feel speechless.”

In the film, Ai says China’s government must become “more responsible, or they’ll have to face some kind of revolution. The longest possibility is 10 years.”

He now calls his 10-year prediction “conservative.” “If [China] doesn’t change, it’s not just the need of the people — but also internally it will not function.”

China’s efforts to contain Ai continue. In April, government cultural officials ordered two of his works removed from a show at a public museum in Shanghai, even though the exhibit was marking the 15-year history of the Chinese Contemporary Art Award; Ai received the CCAA lifetime achievement prize in 2008. .

In June, Ai took to Instagram to savage the removal of his name from a press release about a show at Beijing’s Ullens Center for Contemporary Art celebrating the late curator Hans van Dijk, with whom Ai collaborated closely. Ai also pulled his art from the show. Ai says he was dismayed that the show’s foreign curators had not stood up to pressure from propaganda officials.

Meanwhile, Ai got into a tiff with Jason Wishnow, who cast the artist in a short sci-fi movie. Ai complained that Wishnow was misusing his image to raise funds on Kickstarter and “potentially deceiving” donors about the extent of his involvement.

“So many people ask me, ‘Why, Weiwei, are you acting like this? It’s definitely not going to help you.’ I said, I’m used to this,” Ai says. “If as an art institution or an artist, you are not defending freedom of speech, it’s like a farmer not watering their land, or a factory worker destroying their machine. I think that’s total corruption there.”

Ai says he is cognizant that his celebrity heightens people’s reactions to him. But in his view, he’s just sticking up for his principles. The more famous one becomes, the more important it is to remember “why you become popular.”

“Once you call yourself a celebrity or anyone calls you a celebrity, you are under the judgment of the popular condition.… You’re not supposed to be afraid of this — you are fighting for morals or aesthetics, you are not fighting for your popularity,” he adds. “In the long run, people will understand.”

----------------------------

‘Ai Weiwei: The Fake Case’

No MPAA rating; in English and Mandarin with English subtitles

Running time: 1 hour, 25 minutes

Playing: At Laemmle’s Royal Theatre, West Los Angeles; Laemmle’s Playhouse 7, Pasadena

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.