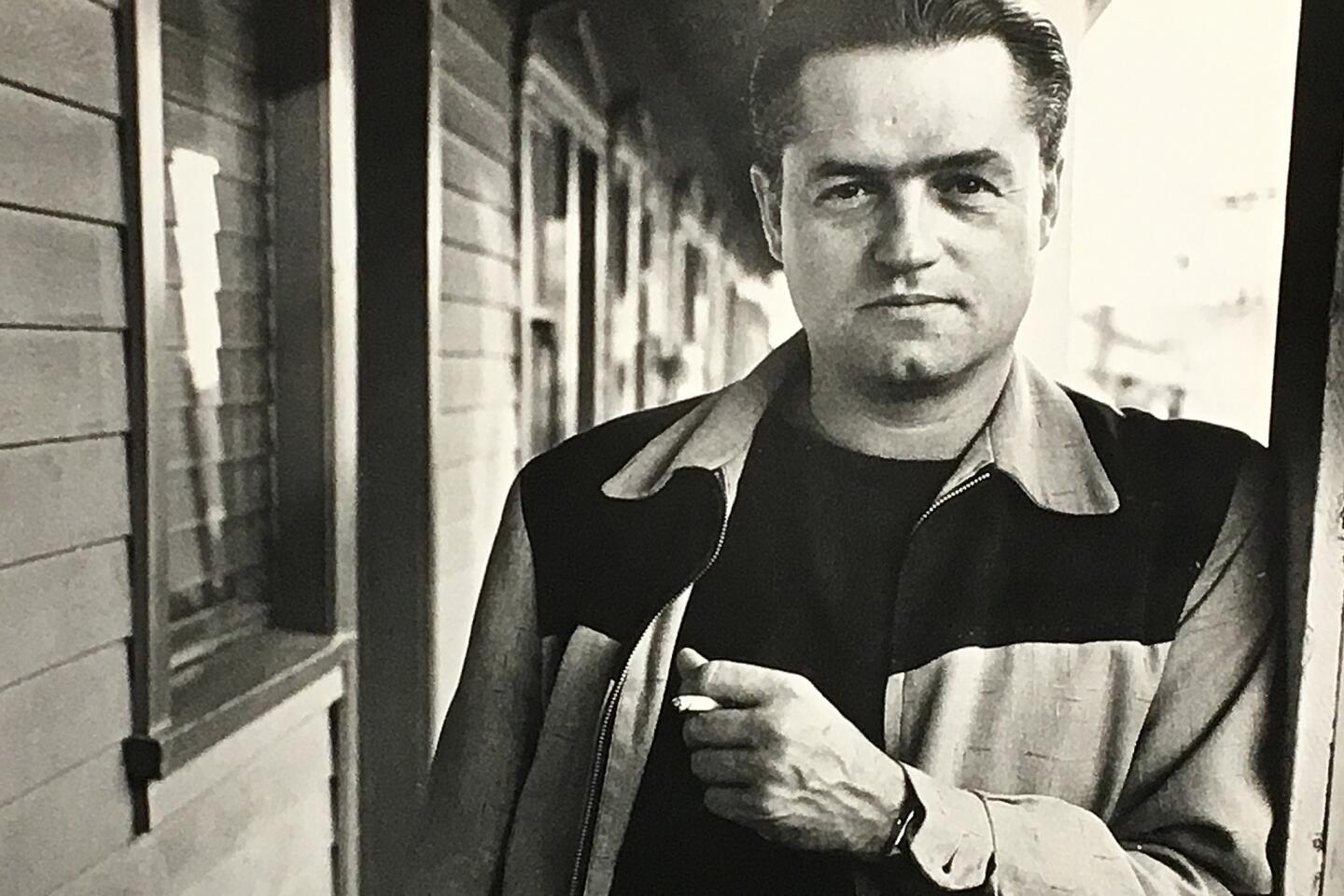

From the Archives: Jonathan Demme on his transition from exploitation movies to his ‘best work’: ‘Silence of the Lambs’

Jonathan Demme, the Academy Award-winning director of “The Silence of the Lambs,” died Wednesday at age 73. In 1991, Demme spoke to The Times about his early films, the struggle to make both art and money, and finishing production on “Lambs,” which he called his “best work so far.” This article was previously published by The Times on Feb. 10, 1991.

Jonathan Demme, who has spent most of his film career being heralded by critics as America’s next great director, remembers a time not too many years ago when it didn’t look like he’d be heralded as anything but a failure.

Demme, spotted early as one of the rising stars in Roger Corman’s school of low-budget filmmaking, got his first big break when he made “Citizens Band” for Paramount Pictures. When newly installed production chief Michael Eisner first saw it, he reportedly asked his production executives why the previous regime had made it.

“I knew we were in trouble then,” Demme said recently over lunch at a restaurant near his home in Westchester County, N.Y., where he lives with his wife and two children. “It was a gargantuan flop. . . . I was pretty unhappy.”

It bombed so badly when it opened that Paramount almost immediately yanked it out of theaters. It got worse. Soon after “Citizens Band” (later retitled “Handle With Care”) faded away, a producer asked Demme for a meeting, leading the young director to feel a momentary sense of reprieve. But when he arrived, he discovered the producer didn’t have a job to offer him; he wanted counseling.

“He wanted to know how it felt to have such a flop because he had a picture coming out in three weeks,” Demme said, still incredulous over the incident. “All I could say was, ‘You mean that’s why you called?’ ”

Still, Demme, now 47, believes he learned an invaluable lesson at a relatively young age: that show business was, after all, a business and that risk-taking directors such as himself had a responsibility to “not make a home movie for an audience of one.”

“I had to take a step back and look at the movie again and go, ‘Good Lord, it’s 90 minutes of people talking to each other over CB radios!” he said. “I mean, Eric Rohmer wouldn’t have touched this!”

“I still think it was a good film. But today I absolutely aspire to the widest audience possible. For a long time, it truly wasn’t essential. If the financiers thought it was a good investment, and if it didn’t make any money, my attitude was, ‘Hey, it was a good picture, and so that’s the end of the story.’ I don’t really feel that way so much anymore.

If it didn’t make any money, my attitude was, ‘Hey, it was a good picture, and so that’s the end of the story.’ I don’t really feel that way so much anymore.

“I don’t think it’s enough to just wind up with a good picture. It’s important for your partners to have their investment returned to them, plus profits. It’s a tremendously important part of the director’s job to try to fashion the script at hand to the broadest dynamic possible. I’m still interested in movies that say something about the human condition in these troubled times in a way that really touches people when they see it. But also in a fashion that can be called entertaining.”

If Demme sounds like the perfect director for Hollywood’s cost-conscious ‘90’s, it may not be unintentional. After his critically acclaimed “Melvin and Howard” in 1980, as well as the startlingly original “Something Wild,” and the dizzy and demented “Married to the Mob,” Demme spent the ‘80s being grouped with that clique of directors whose distinctive style can open a picture almost without the added punch of star power.

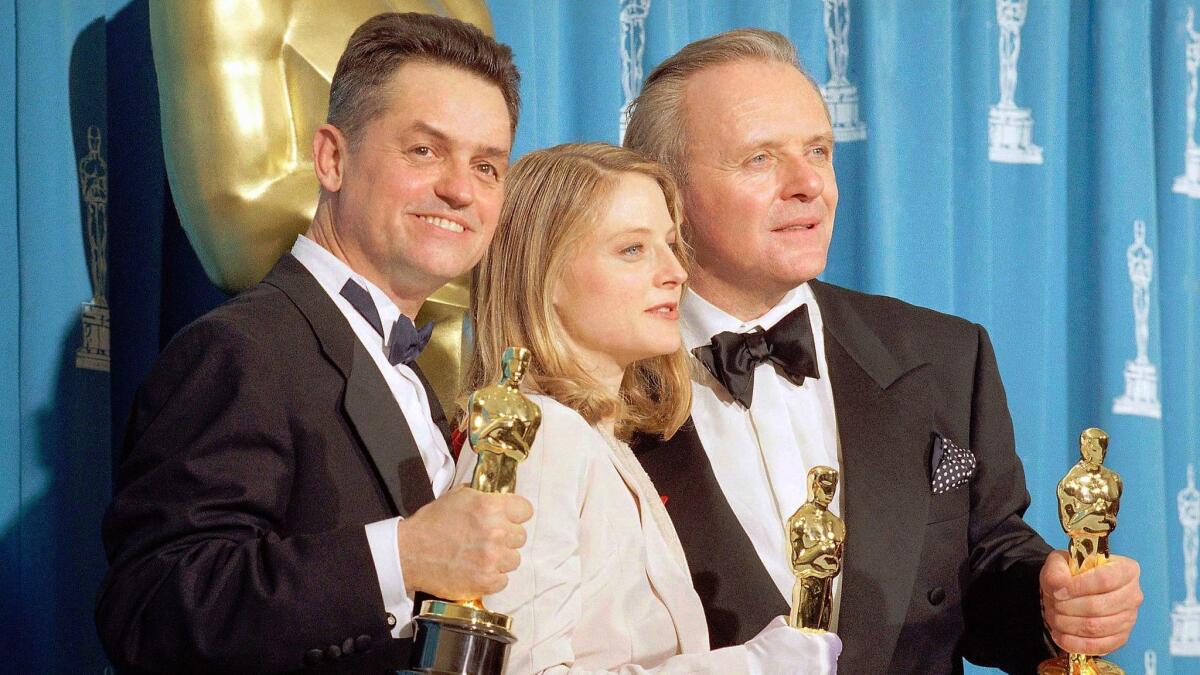

The only question mark still attached to Demme’s name at the highest levels of Hollywood is whether the director can also be commercial. Many people believe that “The Silence of the Lambs,” adapted from a high-profile best-seller, and starring Jodie Foster in one of those rare plum roles offered to women these days, may be the film to shake those doubts. (See interview with co-star Anthony Hopkins, page 27)

Thomas Harris’ novel, a sort of prequel to the book that inspired the Michael Mann film “Manhunter,” was the object of desire in a heated bidding war. When the dust had settled, Orion emerged the winner, having optioned the novel for Gene Hackman’s directorial debut. But Hackman reportedly cooled to the story’s violence--it is, after all, about two monstrous serial murderers: one who skins his victims, the other who eats them--and Orion found itself with a prized property in search of a director.

In the end, Demme’s selection was surprising, but not astonishing. For one thing, he already had a production deal at Orion, for whom he had done both “Something Wild” and “Married to the Mob.” More importantly, he needed a movie that would ease him out of comedic quirkiness into more mainstream subject matter. Still, none of these reasons fully explains why Mike Medavoy, then Orion’s president, would give what was potentially the psychological thriller of the new decade to a director whose only previous sample of the genre--the Hitchcockian “Last Embrace”--was seen by a few appreciative critics and hardly anyone else.

“He hadn’t done this kind of movie, and I thought it was time he did,” Medavoy said. “It was a little bit of a stretch, but all of us believed in him.”

Medavoy, who has since left Orion and become president of Tri-Star Pictures, is raving about a movie belonging to a competitor. “I think (‘Silence’) is brilliant--I knew he was going to do it,” Medavoy said excitedly after a recent screening of the finished picture. “For those people who didn’t think he could do this kind of movie, it’ll convince them that he can do anything.”

It’s my best work so far. I had fondness for other movies I’ve made, but I’m happiest about my work here.

Demme isn’t being modest about it himself. “It’s my best work so far,” he says matter-of-factly. “I had fondness for other movies I’ve made, but I’m happiest about my work here.”

A successful critical and audience response to “The Silence of the Lambs” would almost certainly push Demme into the front rank of American directors, where many people feel he has belonged ever since “Melvin and Howard.” One thing is certain: If “Silence” succeeds, no one can overlook the vision of its director, as is often the case with mainstream hits. Although it’s in the long tradition of edge-of-the-seat thrillers, it is unmistakably a Jonathan Demme movie--offbeat, unpredictable and laced with dark wit.

In an era when innovative filmmaking is more feared than coveted by major studio executives, Demme has been among a handful of daring directors who stay busy making their own kind of movies at Hollywood’s expense. Martin Scorsese has been the leader of that pack over the last 15 years, and it’s a group that also includes such names as Lawrence Kasdan, David Cronenberg and Barry Levinson and--more recently--David Lynch, Terry Gilliam and Tim Burton. To many, Demme’s name belongs near the top of the list.

“He’s the best I’ve worked with,” says actor Anthony Hopkins, who plays the icy psychopath known as Dr. Hannibal (the Cannibal) Lecter in “The Silence of the Lambs.” “I think Demme’s track record as a director of offbeat dark comedy made people surprised that he was going to do ‘Silence.’ I think they thought it was going to be a very light approach. But his real talent is his insight that even in ‘Silence’ a kind of dark-edged comedy is in it all. It’s so bizarre. It’s so frightening. And then there are bits of genius that are funny.”

Like the suspenseful scene where Lecter, though constrained from head to toe, imparts important information while interspersing grotesquely vulgar remarks to a senator’s wife, and then, as he’s about to be led away, calls out to her, “Love your suit!” Without these moments of respite, the audience might drown in the tension. But that is an old device used in many of the old movies that Demme, a life-long film nerd, consumed as a child.

While a junior high school student in suburban Rockville Centre on Long Island, Demme kept a record in composition books of every movie he saw--noting where he saw it, with whom and what he thought of it. He says he continued to summarize and rate every film until years after he graduated from college.

Stranger yet, he spent many of his childhood weekends traveling by bus to other towns and sneaking into building basements where he scanned through “dreadful, yellow, smelly” newspapers looking for movie ads to include in his ever-expanding collection. “I loved the ads because they were just another face of movies,” he recalls.

After his family moved to Florida, Demme attended the University of Florida until his hopes of becoming a veterinarian were dashed when he flunked freshman chemistry. He supported himself by working in a dog kennel but also became a film reviewer, first for the college newspaper and then for a shopper’s guide.

Demme loves to tell how he “stumbled” into the movie business. Actually, credit goes to his father, a publicist, who was promoting the glitzy Fontainebleau Hotel, where movie mogul Joseph E. Levine would dock his yacht.

The elder Demme mentioned that his son, then 21, wrote movie reviews, and Levine was curious. So Demme arrived on deck one day, his scrapbook tucked under his arm. When Levine got to the review of “Zulu,” a movie he’d produced and which Demme had loved, he jabbed the young man in the chest with the hand that was holding the ever-present cigar and said, “You should come work with me.” That was how Demme became a publicist, first for Levine’s Embassy Pictures and then for United Artists in Manhattan.

But Demme and a partner found they “couldn’t keep our hands off cameras.” and spent weekends scrambling around New York City shooting film, writing scripts and eventually making little movies. In 1968, Demme went to Ireland to do unit publicity for Roger Corman, who was just starting up New World Pictures.

“Do you like motorcycle movies?” Corman asked him. That question began a long association in which Demme helped write and produce a series of exploitation movies for Corman’s company.

In 1974, Demme made his directorial debut on “Caged Heat,” a classic women-in-prison picture. From there, his reputation grew until 1977 when he blew his big studio chance with “Citizen’s Band,” or so he thought.

It was Thom Mount, then head of production at Universal, who contacted Demme about “Melvin and Howard,” a story about the real-life Mormon milkman who claimed to have picked up a stranded man in the Nevada desert who turned out to be Howard Hughes. Melvin Dummar had a will he said was written by Howard Hughes, leaving Dummar much of the billionaire’s estate. The will was eventually rejected by the courts, but the entire episode inspired a brilliant script by Bo Goldman and Mount wanted Demme to direct it.

“I read it and I recognized it as a masterpiece, a great American story,” says Demme, who won the New York Film Critics Circle’s award for best director for that film. (Steenburgen and Goldman both won Oscars.) “I loved this whole idea of the American dream unfulfilled on the you-get-rich-and-live-happily-ever-after level, versus having a life that you can feel good about.”

But though critically acclaimed, the movie was never pushed by Universal, Demme complains, adding that one studio executive almost relished its failure at the box office. “ ‘I told you when I read this script, and I’ll tell you again, that you’re (crazy) if you think anyone’s going to go see this picture,’ ” Demme quotes the executive.

“It wasn’t a hideous disaster like some movies I’ve done,” Demme says. “It just never got sold.”

His next movie was “Swing Shift,” a story about women who worked in the California aircraft factories during World War II. Before the movie came out, stories were circulating in Hollywood about post-production reshooting demanded by star and executive producer Goldie Hawn, who, word had it, was being “blown off the screen” by co-star Christine Lahti. Demme says Hawn inserted 28 pages of new material, largely featuring herself. He says he reluctantly shot the new scenes but then quit the project rather than edit them into a revised cut, calling it “a terrible mess.”

Demme’s next film, “Stop Making Sense,” was a triumph. The 1984 concert film featuring band leader David Byrne and Talking Heads won the National Society of Film Critics’ Best Documentary award, and it began to establish Demme as a major talent.

That promise was more than fulfilled with his next four film projects: “Something Wild,” starring Melanie Griffith and Jeff Daniels as a mismatched couple who enter a nightmarish world of violence; “Swimming to Cambodia,” a film version of monologuist Spalding Gray’s performance piece, about his acting a small role in the movie “The Killing Fields”; the 1986 documentary, “Haiti Dreams of Democracy,” about Demme’s favorite island, where paradise and poverty go hand in hand; and “Married to the Mob,” a darkly farcical look at mob life starring Michelle Pfeiffer, Matthew Modine and Alec Baldwin.

He also directed music videos for UB40, Fine Young Cannibals and Suzanne Vega, as well as the anti-apartheid “Sun City,” a paean to the South African freedom movement.

Described by his key crew people as the consummate technician, Demme says his main goal with “The Silence of the Lambs” was to keep the gruesomeness inherent in the story from getting in the way of the humanity of the characters.

It is a measure of his personality as a moviemaker that, when he first read the book at the urgent suggestion of Medavoy (“Under normal circumstances, I would never have read a book about serial murders unless I was stranded in an airport,” Demme notes with satisfaction), he became attracted to the project for what everyone would see as the wrong reason.

In Dr. Lecter, the book has a character of complex evil, a brilliant sociopath as magnetic as he is monstrous. From the cage he dwells in to the 85-beat-per-minute heart rate he maintains while mauling his victims, Lecter is described in the sort of detail that makes filmmakers salivate.

Unless they happen to be Demme. “Which isn’t to say that I didn’t get immediately the magnificence of the Lecter character,” Demme explains. Instead, like so many of his other movies, he was initially attracted to the female protagonist--FBI trainee Clarice Starling (Foster), who through a potent combination of honesty, dignity and bravery, must persuade Lecter to help her track down the serial killer “Buffalo Bill,” so named for his habit of skinning his victims.

“I got three pages into the Clarice character, and I knew I wanted to make a movie out of this,” Demme says. “I love women’s stories. They’re a little harder to find than any other kind of good story, but I love them. Because women are my heroes.

“Don’t you think that by and large women display heightened sensitivities?” he says, letting the question hang for just a beat before continuing. “And that they’re engaged in an ongoing, endless, top-heavy-against-them struggle to achieve what they want to achieve? I’m pulling for women. I’ve got enough estrogen in me to identify with women. I don’t have any difficulty with that.”

Clearly not, considering that nearly all his movies over the past 10 years have championed strong-willed female characters who must struggle to be themselves.

In “Melvin and Howard,” Mary Steenburgen’s glowing performance as a housewife struggling for her own identity won her the Best Supporting Actress Oscar. Melanie Griffith was able to discover new-found power as the freedom-loving star of “Something Wild,” while Michelle Pfeiffer’s escape from the mob and the FBI is the central plot of “Married to the Mob.” Even “Swing Shift,” which was crippled by changes demanded by its star-producer Goldie Hawn and flopped at the box office, had a career-boosting role for Christine Lahti.

In “The Silence of the Lambs,” Foster’s Starling is a young woman fleeing from her past as she chases a killer. “(Demme’s) on the side of the underdog,” says Foster.

After Michelle Pfeiffer turned down the role of Starling, Demme asked actor Ray Liotta--who was given his feature film break by Demme in “Something Wild”--to read with a few actresses. “But Jodie had a pre-interest in the script which Orion let me know about,” recalls Demme. “I knew that she could do Clarice beautifully, and I knew that Clarice would be beautiful for her.”

To those who’ve seen the picture, Anthony Hopkins as Lecter also seems an inspired bit of casting. “I’m happy to say that I was the first one to pop his name out,” Demme says. But the studio wasn’t sure, and Demme says he had to see a number of other actors before convincing them. “I had very high anxiety at the idea of keeping Tony Hopkins on hold while dutifully talking to people who, in my heart of hearts, I didn’t feel would be as good for the part.”

Demme is developing a reputation as an actors’ director, at least among those who’ve worked for him. All those interviewed for this story talked about his open-mindedness, both to the shaping of their characters and his willingness to try things during filming. Hopkins, who calls “Silence” the happiest movie-making experience of his career, says he was very anxious when he did a reading to show Demme how he wanted to portray Dr. Lecter. “Sometimes you have to argue and negotiate with the director,” Hopkins says, “but we did the reading and he came over afterwards and said, ‘That’s it!’ And he gave me a big hug, and I realized that we’d get on beautifully together.”

That collaboration extends to the people behind the camera as well. In recent years, Demme keeps bringing together the same team of filmmakers, including producers Kenneth Utt, Edward Saxon and Ron Bozman, cinematographer Tak Fukimoto, soundman Chris Newman and editor Craig McKay, among others.

Did Demme ever sweat under the pressure of “Silence,” his most high-profile project? Production designer Kristi Zea, who’s worked with him often, responds without any hesitation. “If he did, he certainly didn’t show it.”

ALSO:

One of Jonathan Demme’s last works, an episode of ‘Shots Fired,’ will air tonight on Fox

Demme remembered as ‘one of the real good guys’ and ‘wonderful soulful man’ by his peers

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.