In Tom Patchett’s new play, art is for everyone and Nietzsche is a rabbit

So the director says to the playwright:

“I see them all as rabbits.”

“Really?”

“Yes, and they whisper.”

A pause, slight gasp.

“I’m looking,” says the playwright, “for a way to justify it in my head.”

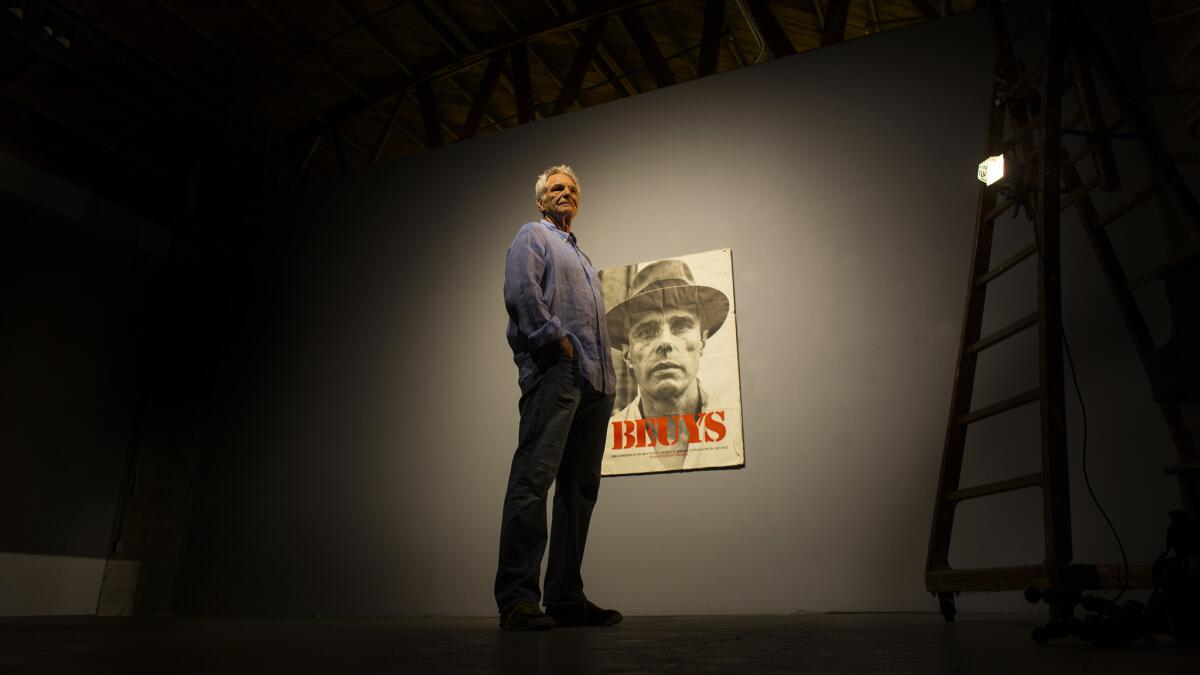

The conversation makes sense when one considers the play is about German avant-garde artist Joseph Beuys, whose works include “How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare.” The vision by Austrian director Georg Nussbaumer to fill a stage with music-playing rabbits eventually won over playwright Tom Patchett, co-creator of the 1980s TV series “Alf,” about a furry space alien living with a suburban family.

Life is nothing if not unfolding symmetries that lead to meaning in unexpected places. The play “Every Hare an Artist: A Beuys Fable” was written in English but will be performed in German at Thursday’s premiere at an old brewery in Berlin. The work’s circuitous journey from mind to stage certainly would have amused Beuys, a World War II airman who died in 1986 after roaming studios and galleries in a fishing vest and fedora while jabbing at the conscience of the world.

“He is a passion, an example to me,” Patchett said. “You can become a better person. You can become a light out of horrible circumstances. He helped to heal what he called the German wound and get past an era of silence. He found a way to express and redeem himself and helped to start communications between Germans and Jews after the Holocaust. He was coming to terms with his own humanity.”

With a gaunt face and supple, if provocative, intuitions, Beuys believed that art should instigate social change and that, through acts and deeds, every person was an artist. He envisioned planting 7,000 oak trees in Kassel, Germany, saying that the trees would live on and that those who planted them would never sit in their shade. For his performance art in “How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare,” Beuys, part of the international Fluxus movement, coated himself in gold leaf and honey and wandered a museum talking to a dead rabbit to symbolize nature, death and the power of ideas.

His sculptures often included felt and animal fat. They were inspired by a story, more apocryphal than real, that told of Beuys being wrapped in the materials by tribal nomads after his plane was shot down over Crimea during the war. Some critics suggested that Beuys, whose work had shamanistic qualities and was shown in a 1979 retrospective at the Guggenheim Museum in New York, less a progressive than a self-mythologizer with totalitarian tendencies. A biography published several years ago suggested he had ties to Nazis.

See the most-read stories this hour »

Patchett spent years working on the play, which unfolds during a memorial service for Beuys attended by artists, friends and philosophers Friedrich Nietzsche and Rudolf Steiner, whom the playwright refers to “as my comedy team.” He staged a reading of the work two years ago in his Culver City art gallery. Friends suggested he bring it to Germany, where, after the involvement of a European publisher and a Swiss producer, it received a 100,000 euro grant from the city of Berlin.

“Frankly,” said Patchett, who is at home in understatement, “I didn’t think it’d be popular here. It’s fairly esoteric.”

Wandering through Patchett’s gallery — he began collecting decades ago — one is struck by the juxtaposition of two seminal forces in his life. Works by Beuys occupy a front room, and through a doorway that seems like a portal to something fantastical, glows a huge bronze and sepia-toned portrait of Alf. Resembling a mashup of a horse, a pig and a troll, Alf, with his flop of hair and big ears, was an international TV hit that let America see itself through the eyes of an alien.

A man cannot always escape, whether he wants to or not, the shadow of his handiwork. Alf is the playful, farcical side of a career that included the intelligence and wit of TV shows such as “Buffalo Bill,” about a caustic talk show host, and “The Bob Newhart Show,” about a prim psychologist. Like those, Patchett’s play on Beuys, a political activist and towering figure in postwar German art, is a deeper exploration, a sharper prism to gauge the world.

But Alf, a clever exploration of its own, is as all-enveloping as he is whimsical, the most widely recognized success in a TV career whose riches have allowed Patchett’s artistic inclinations to flow in other directions.

“You can’t kill the thing [Alf] with a silver stake,” he said. “I’ve invented something that’s never going to go away. People know me for ‘Alf’ but I’d rather be known for ‘The Bob Newhart Show’ or things that were more nuanced. When I’m in Germany, people say, ‘Oh, I love Alf.’ His innocence and naiveté and his being from somewhere else allowed him to critique like Donald Trump only Alf’s not an … .”

Patchett is a tall man with a rugged face, the kind that looks up from campfires in old westerns. His sentences, especially when discussing Beuys, tend toward wending, slipping from postwar art to the cynicism of Nietzsche, from mystical wonderlands to Auschwitz to “growing up as a WASP in Michigan.” Strange and interesting things have happened along the way: “You know,” he said, “I’ve learned that in Europe, the script is the text and the text is simply the premise.”

Meaning actors can quite easily become rabbits. That’s more mischievous than Patchett’s first play, “Wolverines,” a meditation on family rancor set in a Michigan winter. A composer, musician and installation artist, Nussbaumer said collaborating with Patchett on the Beuys project has been “a wonderful experience and a lot of fun — like the play he wrote: deep thoughts and insights coexisting with funny and absurd twists.”

Patchett’s table is stacked with books on Beuys, Nietzsche and others. Some are yellowed, some not. One bit of research opens to another avenue. One train of thought veers toward a dozen new chapters. On and on it goes. Shadings and inconsistencies lead to the magic of art or at least one man’s attempt to discern the world and leave his mark.

“Beuys wanted to create works of remembrance that would last long after he was gone,” Patchett said. “How could he change the future but not forget the past?”

Twitter: @JeffreyLAT

ALSO

Abraham Cruzvillegas’ deft view of L.A. car culture at Regen Projects

‘Merchant of Venice’ set in post-Civil War America? That’s ‘District Merchants’

Los Angeles Ballet dances through its growing pains

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.