How ‘End of the Tour’ became a very David Foster Wallace kind of film

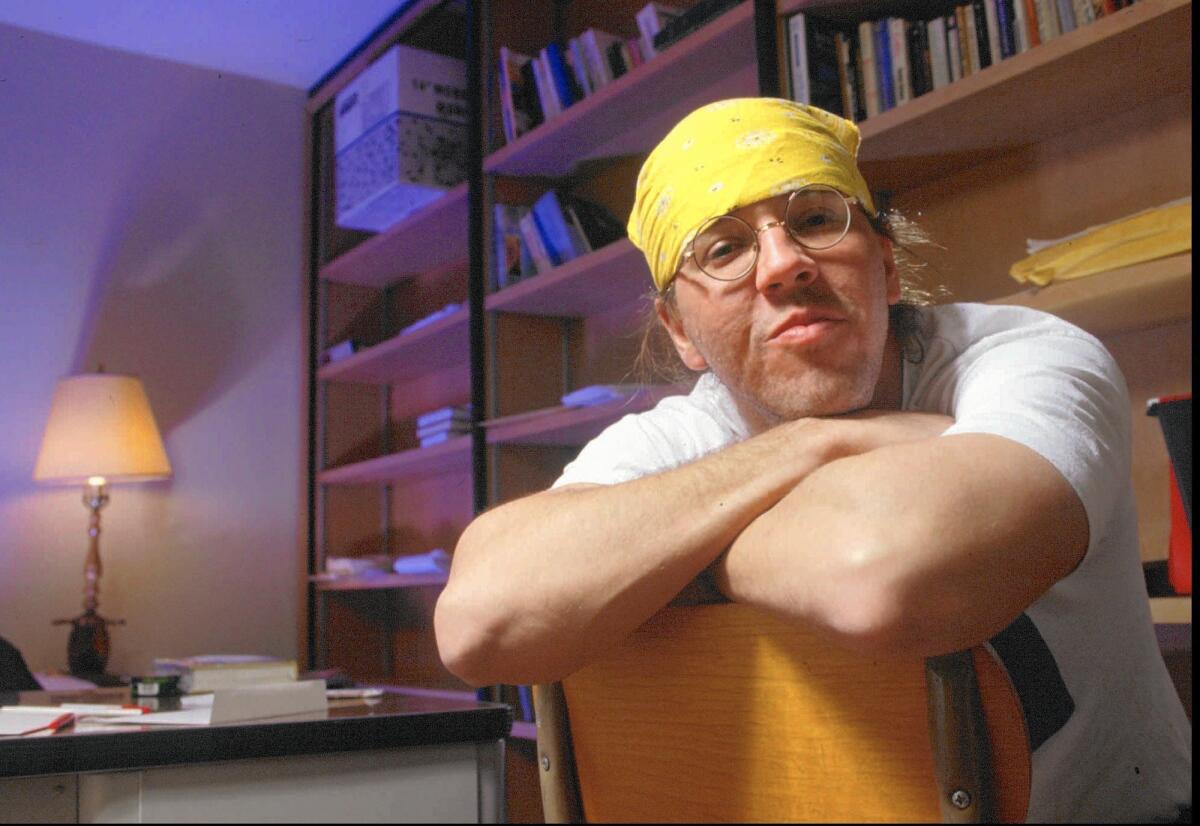

Author David Foster Wallace on March 18, 1996.

Right after the new road movie “The End of the Tour” premiered at the Sundance Film Festival in January, a movie-industry friend texted me her thoughts. Starring Jason Segel and Jesse Eisenberg, “End of the Tour” chronicles a real-life journey taken by then-Rolling Stone journalist David Lipsky (Eisenberg) and the late postmodern novelist David Foster Wallace (Segel) just before Wallace’s career blew up in 1996, and the movie electrified with its ability to tuck meaningful truths into banal Middle American settings.

My friend, however, was not feeling the charge. “Journalist film,” she said tersely, and while I wished she was just paying a compliment to Walter Cronkite, I knew better.

On one hand, I could see her point. “End of the Tour” is a seemingly insular exercise — a film concerned with words and the words of the people who like words.

Yet the essence of her critique — that, as the armchair critic might say, “not much happens” — is also what made the movie special and of interest (I hoped) to more than a coterie of early-adopter writers.

Arriving in theaters July 31, “End of the Tour” tackles heady subjects like the American penchant for self-distraction, the tango between genius and depression, the role of groupthink in value systems and the powder keg that is the mentor-protege relationship. All of these topics come with insight to burn, making the 106-minute movie as packed with ideas as “Jurassic World” is with velociraptor attacks. (It also hasn’t made everyone who knew Wallace happy, but more on that shortly.)

INDIE FOCUS: Sign up for our weekly movies newsletter

Equally important as what the film talks about, though, is how it frames that discussion. Under director James Ponsoldt and screenwriter Donald Margulies (the Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright, basing his screenplay on Lipsky’s book and the Wallace-Lipsky conversations in it), “End of the Tour” broaches its subjects with a minimum of biographical niceties or melodrama. Instead, it relies on ideas, character shadings and charm — the verve of a road-trip movie with the depth of a college seminar.

“One of the pitfalls with a film like this is that you can just end up with two people saying smart things in turn,” Segel said. “Instead, it’s a conversation. And the best conversation I ever heard. Two guys are talking in a car, and it’s weighty and intense, but it’s also fun.”

The idea of unleashing a wild energy on sublime topics isn’t a new trick, of course. It’s one practiced — some would say perfected — by Wallace himself. In works like the essay collection “A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again,” the Kenyon graduation speech “This Is Water” and of course the mega-novel “Infinite Jest,” he scalpeled into our cultural pathologies with keen observation and foot-noted glee.

In a neat formal achievement, then, the movie has managed to take the same sophisticated approach Wallace took in his writing and applied it to a movie about David Foster Wallace.

Which, it must be said, is very David Foster Wallace.

Complicated figure

On a sweltering day near the Yale University campus, Donald Margulies sat in a bookstore contemplating one of modern literature’s most complicated figures. Behind him were copies of Wallace’s “Infinite Jest” and the posthumously published award winner “The Pale King” — suggesting to what degree the author, who in 2008 committed suicide at age 46 in his home in Claremont after a long battle with depression, still loomed over contemporary intellectual life, if not the bestseller list.

Margulies is an unlikely person to bring Wallace to the movie masses. Though much of his work (“Time Stands Still,” “Collected Stories”) centers on artists, the playwright, now 60, was somewhat beyond Wallace’s target audience when the author’s sharp cultural critiques hit the Gen-X solar plexus in the 1990s.

Yet when Margulies’ manager sent him Lipsky’s memoir, “Although of Course You End Up Becoming Yourself” — about Lipsky’s reportorial travels with Wallace in Illinois and Minnesota during the “Infinite Jest” press circuit — Margulies was piqued. Here was a story of two men circling each other in a literary sumo match: Lipsky, a novelist in his own right, envious of his subject’s emerging success; Wallace, already bronzing under the glare of expectation, suspicious of his interrogator.

If the book was just about two writers contemplating their lives, Margulies might had little interest in adapting it. But the story throbbed with psychological vigor.

“It’s all in the subtext,” Margulies said. “Lipsky’s agenda, the competitiveness, Wallace about to hit the stratosphere, the ticking clock of a young reporter going back to New York — it was all there.”

A play might have seemed to make more sense. The book was dialogue-heavy and action-lite, filled with Lipsky’s solicitous questions and Wallace’s self-aware answers. And Margulies had never had a feature screenplay produced before. But he saw in the Lipsky book a classic road movie: two headstrong personalities locked in tight spaces, hashing out the American condition as manifestations of it rolled by the car window.

Margulies, who teaches English and theater studies at Yale, called Ponsoldt, a former student, and asked if he might want to direct his script. With earlier films “Smashed” and “The Spectacular Now,” Ponsoldt, 37, had taken heightened genres — the addiction drama, the teen love story — and filmed them with an unadorned realism. His seemed like the right cool hands.

“We were acutely aware of the genre conceits of the tortured-artist movie,” Ponsoldt said by phone of his overall approach. “You know, where the addiction or disease is reduced to a series of tics and mania, with pages flying off the typewriter or paint off the canvas. I wanted to show a guy who didn’t seem quote-unquote sad, who had a lot of charm, who was very human.”

Lipsky is portrayed with his own complexity; he is interviewing Wallace even as he clearly wants to be Wallace. (Since the trip, Lipsky has concentrated mostly on nonfiction, such as with the well-regarded “Absolutely American,” about life at West Point.)

Ponsoldt said he wanted to eschew the sweep of many famous-artist films, which devolve into biopic cliche. “There’s no God’s-eye point-of-view, nothing omniscient — just a subjective look at a brief window of time,” he said of the movie, which is seen through Lipsky’s eyes and set mainly over just five days.

That favoring of depth over breadth — and certainly this particular moment of depth — may be part of the reason the movie has stirred upset among a few keepers of the Wallace flame. The author’s literary trust — composed primarily of widow Karen Green — and publisher Little, Brown, led by longtime editor Michael Pietsch, disavowed the movie in a statement while it was in production.

In an email this week, Pietsch said he wouldn’t see the film and explained his objections.

“David would have howled the idea for it out of the room had it been suggested while he was living, and the fact that it can go ahead because he’s dead makes me very, very sad,” he wrote. “Anyone who has read David’s writing knows how tormented he felt about being a public figure and his overwhelming anxiety about being on the wrong side of the screen. The existence of a mythification of this brief passage of his life strikes me as an affront to him and to people who love his writing.”

Alex Kohner, the lawyer and co-trustee of the David Foster Wallace Literary Trust, said that filmmakers were dining out on a reputation that wasn’t theirs to use. “People wouldn’t see this movie if it was just two guys driving around. They’re selling David’s good name. They’ve got Jason Segel putting a bandanna on.

“We don’t care if the movie’s good or not good. Under no circumstances would we or David have agreed to this,” he added. It’s not yet clear if there will be any legal action, though; recourse on these grounds is far more limited after a person has died.

Kohner said that he and his law partner had numerous correspondences with representatives for Segel and Ponsoldt urging them not to make this movie before it went into production. Ponsoldt would later call Green, who offered him the rights to a Wallace book in the hope that it would be the author’s work, and not his persona, that would be memorialized on screen. When the movie forged ahead, Kohner, Green and Pietsch decided to go pbulic and issued the statement during production. (Green, incidentally, is not portrayed in the movie; she would not meet Wallace until years after the 1996 trip.)

Ponsoldt said that he understood the group’s position but thought Green and Pietsch misread his intentions.

“I haven’t personally experienced it to know what happens when someone you love is being played by an actor,” he said. “But we were telling David Lipsky’s story ... which came out years before.” He added, “We made this movie because we love and revere [Wallace’s] writing, and we want to depict him with empathy and humanity. I hope anyone who sees the film understands that.”

Segel said he had similarly pure motives.

“I didn’t hear about the issue until we’re almost done shooting,” he said. “I really do understand it’s a very complicated, emotional and uncomfortable situation. My personal feeling in taking on the movie and especially in seeing it is that it’s a real extension of David Foster Wallace’s themes and writing.”

Viewers will make up their own minds on the specifics of the portrayal. While the film certainly stays far away from the idea of “St. Dave” — the ironic nickname some friends have used to describe what they see as an unhealthy deification of the author — and does offer moments of prickliness, Segel’s nuanced performance leaves an impression of sympathy and vulnerability. Wallace on the cusp of stardom is worried about his privacy, which is shrinking, as well as the pressure, which is building.

“There are struggles in a situation like this that are very real,” Margulies said. “How do you move on when there are now expectations in a place where formerly there were none? How do you move on when peers are rating your work and comparing it to what you’ve done in the past?”

Literary greats

Movies with literary greats at their center — C.S. Lewis in “Shadowlands,” Dickens in “The Invisible Woman”— tend to be largely about the writer’s difficult life, less so about the ideas that made those difficulties worthwhile.

“Tour,” on the other hand, teems with ideas--not least of which is the author’s much-mined concern with entertainment’s deleterious effects and the power of technology to lubricate them.

“Wallace was anticipating things that are banal to us — that famous Facetime technology in ‘Infinite Jest’ for instance, which we now live with in an unquestioning way,” said Chritophers Schaberg, a professor at Loyola University New Orleans who teaches a class on the author. “Everything we’re seeing now with distraction and constant connectivity were matters Wallace was very aware of 20 years ago.”

But far from a jeremiad, Wallace offered these cautions in a spirit of solidarity. It’s a feeling that’s captured subtly in the film, as Wallace is seen indulging in trash TV and junk food while on tour for the very book diagnosing those symptoms.

“I feel like Wallace wasn’t as much a preacher as he was somebody sending out a distress signal,” Segel said. “It’s someone right in the middle of the pack, saying, ‘Does anyone else feel this way?’ He’s just saying it more eloquently than any of us could say it.”

Or as Wallace offers in the movie: “Writers aren’t smarter than anyone else. They’re just more compelling in their stupidity, or their confusion.”

There is something paradoxical about Wallace as a public figure. He is both of the moment and encased in amber, the latter of which a movie will do little to ease. His is the rare modern work to be studied like a classic, and that duality can have a strange effect, making him identifiable yet also reinforcing the deity myth.

Though Wallace was fiercely opposed to irony, he also had the (post)modern habit of piling up the layers, and there are many in “End of the Tour.” We are watching Ponsoldt interpret Margulies interpret Lipsky interpret Wallace interpreting the world, and one might ask how the message has been translated or distorted along the way.

Rendering Wallace anew raises other questions. The author famously argued that TV-viewing is the go-to vice of writers, who crave personality observations without the social burdens. Watching the movie, one can’t help wonder what someone so frequently critical of TV’s grip on the culture would make of the medium’s current golden era, when it has an even greater hold but perhaps takes a more novelistic approach.

The ultimate Hollywood-themed thought experiment remains hypothetical, though it does offer some tantalizing possibilities in the mind’s eye. “What would really be fun,” Schaberg said, “is to imagine what David Foster Wallace would write about this movie.”

Which, needless to say, would have been very David Foster Wallace.

Twitter: @ZeitchikLAT

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.