Jennifer Fox’s drama ‘The Tale’ brings #MeToo to Sundance

Reporting from Park City, Utah — When Jennifer Fox was 13 years old, she had a relationship with her 40-year-old track coach. For decades, she considered their romance consensual — her first boyfriend, she’d tell those closest to her, just happened to be an older man.

It wasn’t until Fox was 45 that she realized the relationship constituted sexual abuse.

Her memory of her adolescent experience began to shift when, around 2006, her mother was cleaning the house and stumbled across a story that Fox had written as a girl. The seventh-grade assignment, a narrative the teenager had titled “The Tale,” was about her connection with a riding instructor, Mrs. G, and running coach, Bill (both character names created by Fox). In the piece — which she’d submitted as a fiction story — Fox described how, at Bill’s coaxing, she lost her virginity to him.

“If this is true, it’s a travesty,” Fox’s teacher had scribbled on the back of the paper. “But since you’re so well-adjusted, it can’t be true.”

Fox, however, says “The Tale” was true, and reading it as an adult, it became clear to the filmmaker that what had happened to her at age 13 was actually far darker than she’d remembered. For roughly 30 years, it seemed, she’d viewed the trauma through rose-colored glasses as a means of survival. Fascinated by how her memory had warped, Fox decided to dive back into her history and turn her story into a screenplay.

The resulting film, which Fox directed and also called “The Tale,” debuted at this year’s Sundance Film Festival, and was acquired for release by HBO, at an unexpectedly timely moment — in the midst of the #MeToo movement, when the culture is grappling with how to deal with sexual harassment and assault.

FULL COVERAGE: Sundance Film Festival 2018 »

Due in part to its graphic verbal and physical depiction of the abuse Fox says she suffered, the movie has left festival goers shell shocked. An end title card states: “Based on ‘The Tale’ written by Jenny Fox, age 13. Identifiable elements of characters, places and events have been changed in the film.” After its premiere here on Saturday, the crowd rose to its feet as the filmmaker and her cast took to the stage, actor Jason Ritter even beginning to cry.

“The reason I put my name on it was so that nobody could say it was a lie,” Fox said, a few days after the film’s unveiling. “Nobody could chop the film down by saying, ‘Oh, it’s just fiction. Sexual abuse doesn’t look like that.’ I am here to represent that it does.”

Fox — who splits her time between New York and Zurich, Switzerland, where her husband hails from — has a documentary background. Her debut movie, “Beirut: The Last Home Movie,” about a noble family living in the midst of the Lebanese civil war, won Sundance’s Grand Jury Documentary Prize in 1988.

“The Tale,” which was shot two and a half years ago, was almost headed to Sundance last year — but Fox said she “pulled it” at the last moment to continue the complicated editing process.

The movie is the director’s first narrative feature, but she interviewed people to inform the project. Shortly after her mom found “The Tale,” Fox reached out to Mrs. G, Bill, and the other girls who had been pupils alongside her at a summer program. She met with them all under the guise of “old times,” then rushed home to transcribe anything she could remember from their conversations. The research eventually helped to create the dialogue in “The Tale,” as did Fox’s girlhood diaries and, of course, that story she wrote in seventh grade.

“My goal was not to ask: ‘Did this happen?’ Because I always remembered it,” explained Fox, now 58. “It was: ‘How and why did it happen,’ and ‘how and why did I spin it as a positive story?’ I didn’t want the outcome to be that I’ve now replaced it with a negative story. The truth is that both stories exist simultaneously. As a child, I loved these people — I thought I was trading love for my sexuality. What I understood as an adult in this investigation is that the trade was an unfair one.”

A native of Philadelphia, Fox was one of five children. Her parents, she said, had come out of the Depression and were trying to live the American dream — raising a big family, getting involved in the community and maintaining an active social life. They were loving, but they were overextended, and Fox often felt neglected.

So when she went to the camp, she finally found the attention she was so desperately seeking. Mrs. G, who ran the program out of her home, was British and beautiful — both a homemaker and an accomplished athlete. Fox, who thought her mother always seemed to be “under the thumb” of her father, found a female role model in Mrs. G.

“I would have done anything for her,” she recalled. “Build a bridge? I’m there. Stay up all night digging trenches? I’m there.”

Mrs. G ran the camp like a military organization, and Fox thrived with the routine. She excelled at running, and Bill — who led the morning jogs — quickly took notice of her. Before long, he was showering her with attention, and Mrs. G arranged for her to spend time alone with him at his home.

“I never, ever saw him as boyfriend material,” Fox said. “But I was shy. I was skinny. I was short. I was underdeveloped. When I played Spin the Bottle, I was the girl everyone didn’t want to kiss. I was not Lolita. So I drank in the attention he gave me.”

Still, Fox loathed being intimate with Bill. She had never kissed a boy — let alone French kissed one — so having his tongue in her mouth was a particular kind of “hell,” she said. She was so ticklish that every time he touched her, she would freeze in order not to move or laugh.

“It was a kind of moment-to-moment torture,” explained Fox, who said she’d vomit after sexual encounters with Bill. “But I felt so strongly that what I was gaining on the other side was worth the price. And that’s the problem with child sexual abuse — a kid can’t make those choices, but as an adolescent, those are the boundaries you’re pushing. You’re trying to have agency. I was thinking: Whatever the price is, I don’t know, but I’m willing to pay it because I am my own person.”

Filming the sex scenes between a young Jenny (played by a then 11-year-old Isabelle Nélisse) and Bill (Ritter) proved complicated — both emotionally and logistically. During the most intimate moments, Ritter acted opposite a 22-year-old body double so that Nélisse was not exposed to anything sexual in nature. Nélisse’s reaction shots, meanwhile, were filmed with the actress alone on a bed, as Fox suggested non-sexual cues: “Act like a bee is stinging you. Act like you hear a dog barking. Act like you’re eating an ice cream.”

As a result, Nélisse was never exposed to any graphic dialogue — though she did read the script in its entirety prior to signing onto the movie — and was accompanied on set by her mother, a studio teacher, a SAG-AFTRA representative and a psychiatrist.

“We had a lot of conversations behind the scenes about ‘Do we have to go this far and say all these things?’” Ritter said, referring to some of the more disturbing sexual conversations. “But saying some of those lines with that much honesty and openness is part of this. We can’t just look at the parts where Bill and Mrs. G mentor Jenny or make her feel special and then shy away from the darker stuff. The beauty and the complexity of the movie is that both things existed.”

On set, Fox was extremely open with her actors, freely answering questions about her experience and sharing pictures and documents from her childhood. Still, Ritter and Laura Dern — who plays Fox as an adult, and had to cancel a trip to Sundance due to illness — struggled to separate their own anger toward the situation from Fox’s experience.

“I had to keep talking her down off the bridge and say, ‘No, Laura, I’m not angry at this point in time. What I felt until I was in my 40s was I was cared for, loved and nurtured by Bill,’” Fox said. “Abuse is complex, and our society wants to make it black and white. Telling it complexly does not change the fact that it was abuse. When we simplify it, we hurt everybody.”

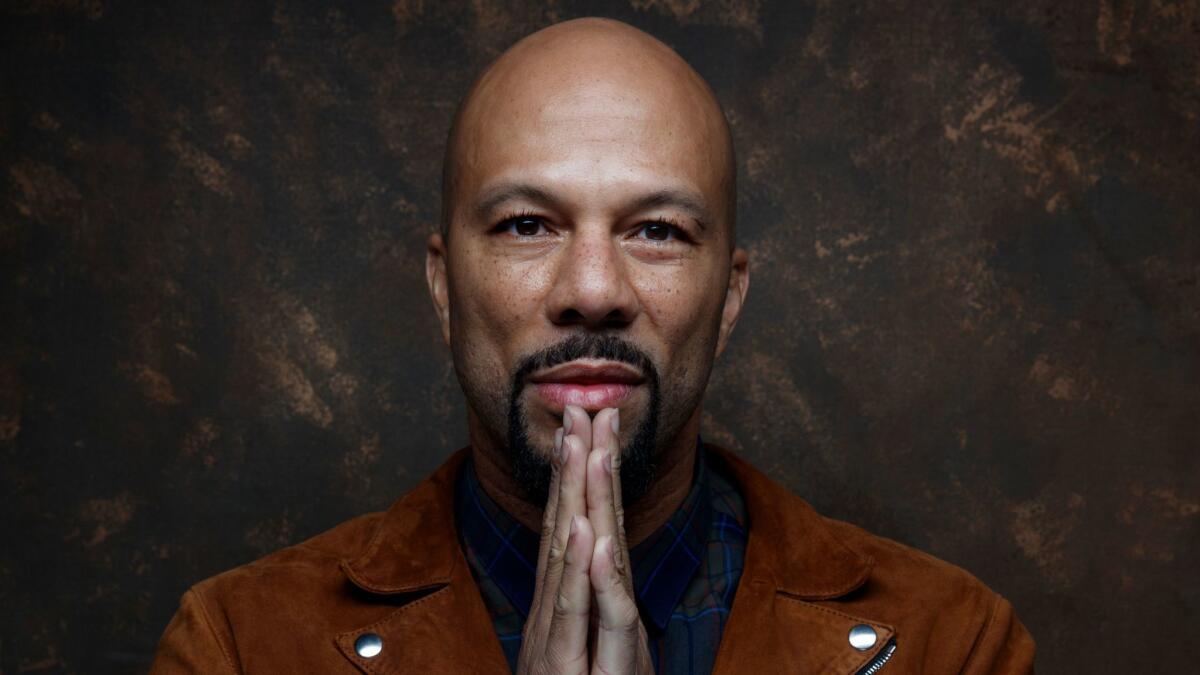

Common, who plays Fox’s fiance when she is an adult, said working on the movie had served as an “awakening” for him — forcing him to confront his own role in the #MeToo movement.

“I’m really trying to learn and say, ‘How can we change this culture for real?’ ” the musician-turned-actor said, sitting next to Fox. “I think ‘The Tale’ is happening at the right time because the world is changing for the better. To see women empowered in the way that they are right now, to see men having to come to grips with the culture we’ve created and been a part of — it’s a beautiful thing, but it’s a painful thing. This film is part of that change.”

The HBO pickup, which was announced as this year’s Sundance was nearing its close, is unusual in that the premium cable network rarely acquires narrative films directly out of festivals. But even though the deal, said to have carried a price tag in the high seven figures for global rights, means the film will not be released in theaters, it still lines up with Fox’s vision for getting the film to audiences.

“We have been building an outreach and audience engagement campaign to piggyback with whatever distributor we get,” she said before the HBO deal was announced. “We want to build this to use a dialogue, community by community, in schools and religious groups. We want to make this thing a commercial success and an activist success.”

Going through the process of telling her own story — before #MeToo exploded worldwide — has given Fox a deeply personal understanding of issues that are now playing out everywhere from newspaper headlines to private conversations. And she sees much to be hopeful for.

“It is a very slippery slope what’s true. It’s a legal issue, a societal issue — how we walk forward and be careful of how not to accuse people flippantly. However, I think it’s an incredible moment that things women have been living with for centuries are being brought to the surface and being [heard].”

Even so, Fox declined to identify “Bill,” saying she is not interested in “outing” him. Instead, she hopes her story serves to prevent sexual abuse, and as an exploration of how we “tell ourselves stories about who we are.”

“I’m not always comfortable saying, ‘This is my story,’ but that’s what I can offer,” she said. “Being an artist isn’t comfortable. We are going to die. Our lives are short. Time is passing. I’m 58. I don’t have much time — let me do something meaningful, or else, why? I want to live. And the only way to do that is to risk.”

2018 Sundance Film Festival

Video: Adapting 'Hamlet' for a woman's point of view in 'Ophelia'

Video: 2018 Sundance Film Festival Boomerangs

Video: A behind-the-scenes look at the 2018 Sundance L.A. Times photo/video studio

Video: The Kronos Quartet premieres its live documentary

"The Kindergarten Teacher" shows something many movies don't

Video: Filmmakers share thoughts on the future of women in film, the U.S. and storytelling

Follow me on Twitter @AmyKinLA

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.