The cantankerous glory of David Crosby, who hates Spotify, wants to reunite CSNY and saved at least $25,000 growing pot

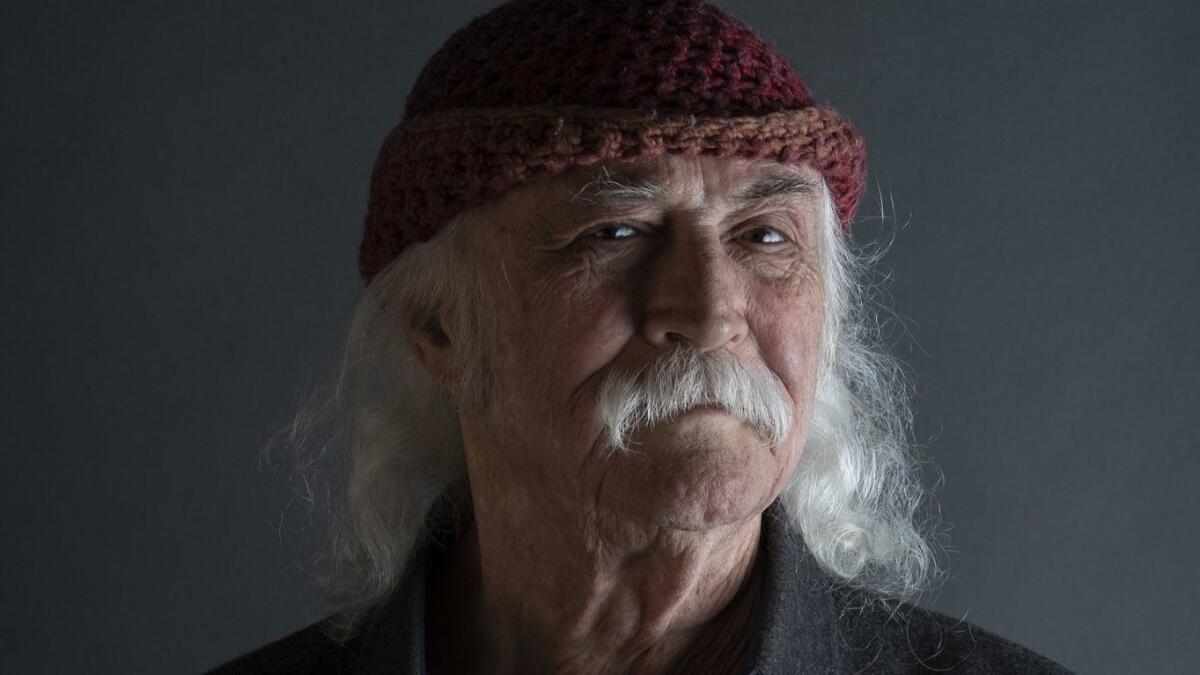

David Crosby knows he’s going to die soon. He’s diabetic. He’s had a liver transplant as a result of hepatitis C. He’s survived three heart attacks and had eight stents put into his chest. He expects his heart will stop again in the next couple of years, and then there won’t be anything else doctors can do to keep him alive.

And he’s mad. Because even at 77 there are so many things he still wants to learn — “three languages, four sciences, eight kinds of history.” He wants more time with his wife of 41 years, Jan. And, of course, he wants to make more music.

“I’m concerned that the time I’ve got here is so short, and I’m pissed at myself, deeply, for the 10 years — at least — of time that I wasted just getting smashed,” said Crosby, who for decades battled addictions to alcohol, cocaine and heroin. “That’s really a waste. I’m supposed to be making music. I’m ashamed of that.”

He spent so long as a junkie — “as low as a human being can go” — that now he’s trying to be somebody he can be proud of. And part of that means taking a hard look at all of his mistakes, namely the behavior that helped drive a rift so deep between him and Stephen Stills, Graham Nash and Neil Young — who together formed the folk rock supergroup CSNY — that they no longer speak.

It’s why he said yes to “David Crosby: Remember My Name,” a documentary about his life that opens in select cities July 19. In the film, which was acquired by Sony Pictures Classics after its debut at the Sundance Film Festival earlier this year, the musician speaks frankly about his anger issues, financial woes and fear of mortality.

He also talks a lot about CSNY, trying to take some responsibility for his role in their falling-out. “One of them hating my guts could be an accident,” he says in the film. In other words: It’s not just happenstance.

Crosby is open about his hope that his former bandmates will see the doc. He isn’t interested in a “walking therapy session” with them, hashing out who said what and when. He just wants them to see that he’s a “good guy” now and that he’s doing the “right thing” by “making music, as fast and as best” as he can.

“I don’t really care how it goes down,” he said of a possible reconciliation. “I care about this: There is a job that we do. CSNY does a really good job as a town crier. We were better at it than anybody. And now is a real good time for that job. I get that probably 10 times a day on Twitter. ‘Will you guys quit squabbling and do your gig? Because we need you now. You are our voice.’ OK. I agree.”

So how is it going to happen?

“I don’t think it is,” he said matter-of-factly.

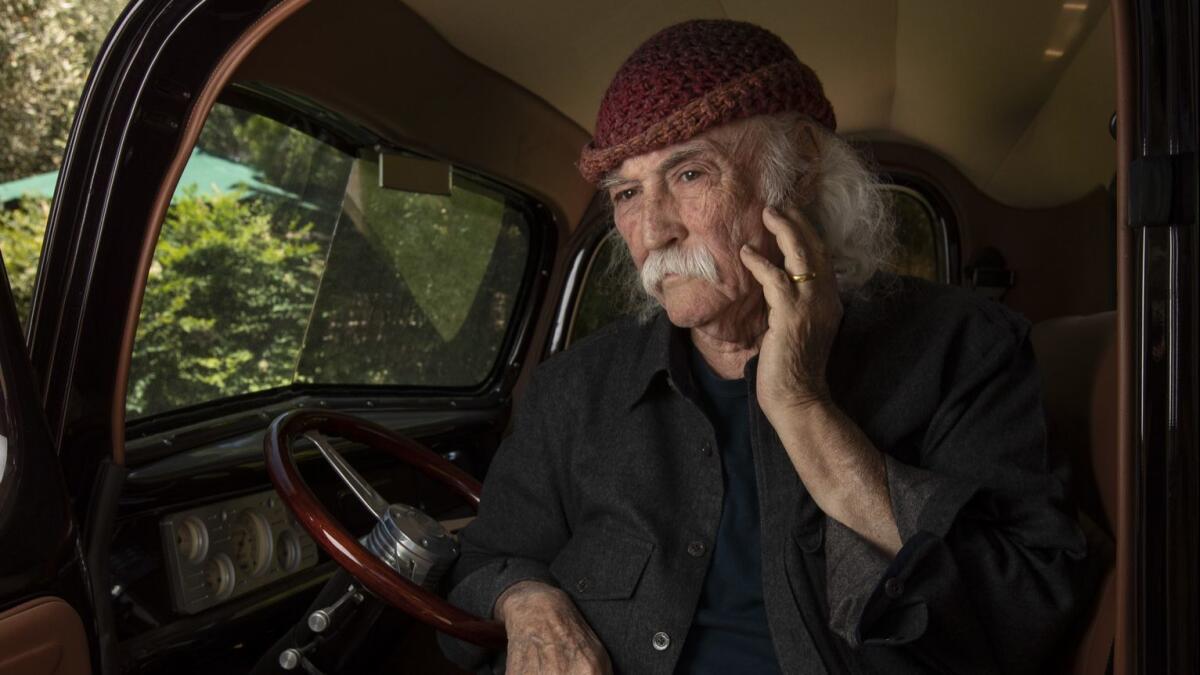

It was January, and Crosby was holed up inside a cabin on a snowy mountainside at Sundance, trying to keep warm. He was wearing his signature faded red beanie, knit for him by his wife, who was seated nearby at the kitchen table. The couple, who share a ranch house in Santa Ynez, are deeply bonded. When he dies, she says in the movie, she “might just disappear. It’s gonna be hard to take another breath when he’s not here.”

“When I hear what she’s afraid of, yeah, it makes me want to cry too,” he said. “I’m afraid of it too. But the fact is, we still love each other. And that’s the good stuff. I’m looking at the gift I’ve been given, which is to share a lifetime together. That doesn’t happen by accident. I’m not easy.”

By his own admission, Crosby was not always a good partner. In the film, he describes how his coke habit made him obsessed with sex, leading him to become a “selfish and wacko” guy who slept with hundreds of women, including Joni Mitchell.

But Jan changed him. She’s “patient and loving” and watches out for him. At the cabin, when she observed her husband pulling out his Pax 3 to offer up the Blue Dream she grew in their backyard, she quietly suggested: “Don’t forget to talk about the movie!”

“She grows fantastic pot,” he said, taking a pull from the vape. “I think we probably saved between $25,000 and $40,000 bucks last year. My son smokes it like a chimney, and we smoke it at night when we go to sleep. The point isn’t to get blottoed. I think weed is basically OK. I don’t think it does a lot of harm. I think it’s like wine and beer, that level.”

Still, his body is far more fragile than it used to be. On his tours, the three hours he’s on stage, he said, are heaven.

“But the other 21 hours are a bitch,” he explained. “I hurt a lot. My body is falling apart. And so that part is really hard. It’s really hard to go out on the road. You try being 77. You’d be tired too, honey! You’d be some serious tired. You wait and see. It beats you up. You don’t have stamina. I walk two blocks, I’m beat. I used to be able to walk 10 miles.”

Despite Jan’s objections, however, he stays on the road — largely out of financial obligation. He said he has no savings, and he’s livid about how little he makes off his old music as a result of streaming companies: “I don’t cut Spotify any slack. They’re thieves. They’re stealing from me. It’s not right, and I can’t shut my mouth about it. I’m sorry. I don’t mean to be a pissant about anything, but that’s a real wrong that’s being done. It’s as if you worked for three weeks and they paid you a nickel. You’d be pissed.”

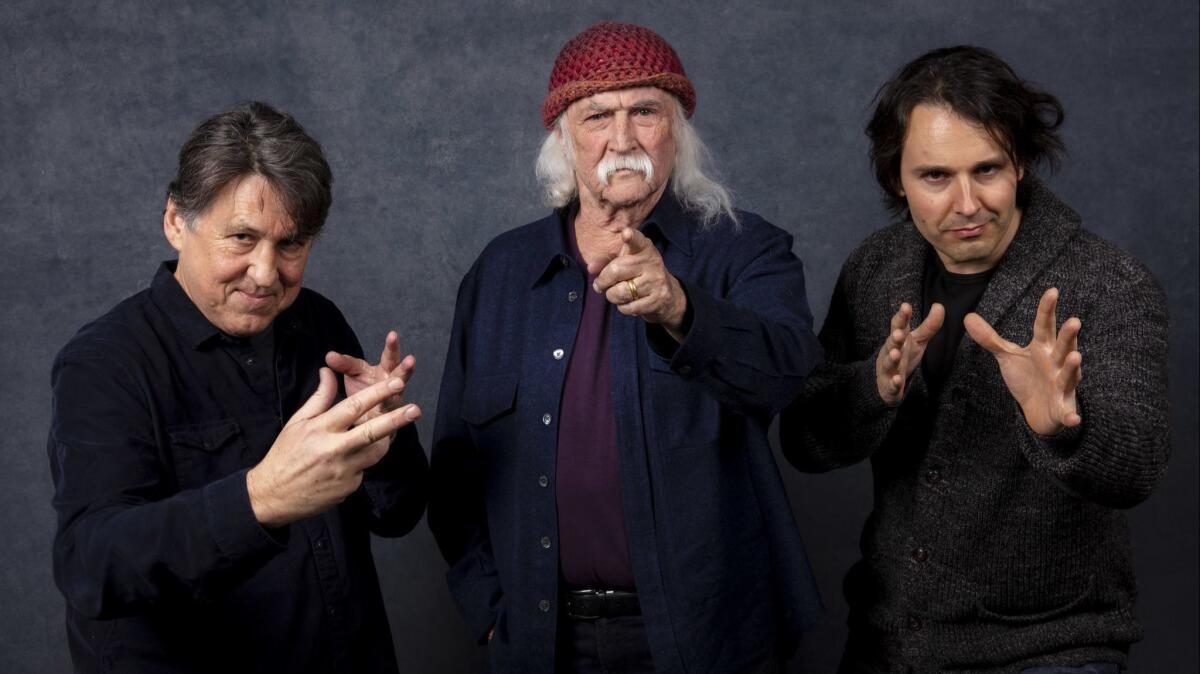

Crosby has always been more candid than most rock stars. That’s why producer Cameron Crowe had a feeling he would make a strong documentary subject. But the film wasn’t his idea; it was the brainchild of A.J. Eaton, a first-time feature director who met Crosby through his brother. In recent years, as Crosby has released four solo projects, he’s collaborated with a handful of lesser-known young musicians, one of whom was Eaton’s sibling, Marcus.

After stopping by one of their recording sessions, A.J. Eaton and Crosby struck up a friendship, riffing on space exploration over lunch and listening to Pat Metheny together. The filmmaker hadn’t been a massive fan of Crosby’s music — familiar only with hits like “Our House” and “Southern Cross” — but was impressed by the “luscious, jazz-inspired” stuff he was producing in his third-act renaissance.

Eaton suggested shooting some footage of the creative process, just for posterity. Crosby agreed, not thinking the project would amount to much.

“But he asked me some intelligent stuff, so I extended it a little further,” Crosby recalled. “It felt like pay dirt. It felt good.”

Then, during a meeting at J.J. Abrams’ production company, Bad Robot, Eaton serendipitously crossed paths with Crowe. The “Almost Famous” director knew Crosby well, having interviewed him roughly a half dozen times over his career as a rock journalist.

In a 1977 cover story for Rolling Stone, Crowe became so enmeshed with what was then Crosby, Stills & Nash that he even became part of one of their arguments. Displeased with Crosby’s answers to some of Crowe’s questions, Nash left a group conversation and retreated to his room. Crosby and Crowe followed.

“Please,” Nash pleads, “don’t drive me out of my room. I came in here to escape you all.”

“Sorry,” Crosby says, “it’s his fault. He didn’t ask me my favorite questions — what I have to say to the 15-year-old girls of America, what kind of weird sex trips I’m into, where I buy my clothes, nothing.”

So when Crowe learned about Eaton’s project that day at Bad Robot, he was intrigued. At the time, he was busy making the Showtime series “Roadies” and turned down an initial offer to come aboard as a producer. But he agreed to do one interview with Crosby for the film to help out.

Crosby was thrilled by the prospect of reuniting with Crowe, whom he said he met when the writer was 17, “stuck a joint in his mouth and introduced him to some girls.” (“Actually, he stuck a joint in his own mouth, and introduced me to his girlfriends,” Crowe later clarifies.)

Eaton, who calls Crowe one of his “directing heroes,” was equally excited.

“He has a level of knowledge from his experience interviewing Crosby, and Crosby responds to him differently than he does me,” said the director.

“Crosby never threw a question out. He never dodged,” added Crowe. “It was like, here’s what a guy does when he’s really gonna go there and not waste your time talking about his life. No rock figure that has ever been present for so much has ever been so honest about what it was really like. That’s the kind of interview I want.”

The first sit-down between Crosby and Crowe went so well that they both agreed to another, and ultimately, the filmmaker changed his mind about producing the movie to help Eaton secure financing.

Though Crosby’s former Byrds collaborator Roger McGuinn is interviewed in the documentary, Eaton and Crowe made the conscious decision not to ask Young, Stills or Nash to participate. (Some of them, however, do voice harsh opinions of Crosby via archival footage.)

“Why do the cavalcade of talking heads?” Crowe asked. “We’ve seen it. And in fact, so many of those people that we could have talked to do four or five of these interviews for docs a day. So let’s let them rest. Let’s have him tell the story.”

Not that the shooting process was always joyful. While Crosby was happy to sit for reflective interviews, he was less interested in taking physical walks down memory lane. When the filmmakers suggested they take a trip to Laurel Canyon, where CSNY lived at the height of their fame, Crosby balked. During a visit to the Laurel Canyon Country Store, he was curt, trying to downplay the neighborhood’s importance in his life.

I’m a highly flawed human being, and I’ve made lots of mistakes. This wasn’t easy. It was very painful.

— David Crosby

“It was just where we got the groceries,” he says in the film, walking around the store and looking at vintage pictures of local musicians on the wall. “The only people I knew were the Doors, and I didn’t like ’em. [Jim] Morrison. What a dork.”

“He was defiant,” Eaton said with a laugh. “But we needed to get out into the world to get a different type of response. When he walks up and looks at Joni Mitchell’s house for the first time, that’s gold, in my book.”

Upon reflection, Crosby admitted he was moved by looking at the home on Lookout Mountain where “Our House” was written. And while he’s sometimes depicted in “Crosby” as a “crusty old fart,” he’s OK with that.

“I’m a highly flawed human being, and I’ve made lots of mistakes,” he said. “This wasn’t easy. It was very painful. But you know, I did 14 years in AA. And if it teaches you anything, it teaches you that being honest works.

“These [filmmakers] weren’t interested in a shine job. I wasn’t either. I certainly wouldn’t call it merciless, but I would call it relentless. They asked me the hard [stuff]. Over and over again. Cameron asked me the hardest questions I’ve ever been asked.”

One of them was why, after everything, he doesn’t just show up on Young’s doorstep and make things right. He tells Crowe he doesn’t know where that doorstep is.

Of course, he could find out. But there’s something holding him back.

“Neil, you don’t just walk up on Neil. That’s not gonna work,” he said, showing a hint of that trademark defiance. “I’ve known him 40 years. That’s not how to do it.”

Perhaps his pride is getting in the way. Still, Crowe remains hopeful that the movie could serve as a healing bridge between Crosby and his old friends.

“He may not show up on Neil Young’s doorstep, but maybe a copy of this movie will show up on the doorstep, and that will be what he has to say,” said Crowe. “It’s another way of saying: ‘This is how I feel about you.’ ”

Follow me on Twitter @AmyKinLA

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.